3.1 The Importance of Delivery

Click below to play an audio file of this section of the chapter sponsored by the Women for OSU Partnering to Impact grant.

“We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.” -Will Durant

Some surveys indicate that many people claim to fear public speaking more than death, but this finding is somewhat misleading. No one is afraid of writing their speech or conducting the research. Instead, people generally only fear the delivery aspect of the speech, which, compared to the amount of time you will put into writing the speech (days, hopefully), will be the shortest part of the speech giving process (5-8 minutes, generally, for classroom speeches). The irony, of course, is that delivery, being the thing people fear the most, is simultaneously the aspect of public speaking that will require the least amount of time.

Consider this scenario about two students, Bob and Chris. Bob spends weeks doing research and crafting a beautifully designed speech that, on the day he gets in front of the class, he messes up a little because of nerves. While he may view it as a complete failure, his audience will have gotten a lot of good information and most likely written off his mistakes due to nerves, since they would be nervous in the same situation!

Chris, on the other hand, does almost no preparation for his speech, but, being charming and comfortable in front of a crowd, smiles a lot while providing virtually nothing of substance. The audience takeaway from Chris’s speech is, “I have no idea what he was talking about” and other feelings ranging from “He’s good in front of an audience” to “I don’t trust him.” So the moral here is that a well-prepared speech that is delivered poorly is still a well-prepared speech, whereas a poorly written speech delivered superbly is still a poorly written speech.

Despite this irony, we realize that delivery is what you are probably most concerned about when it comes to giving speeches, so this chapter is designed to help you achieve the best delivery possible and eliminate some of the nervousness you might be feeling. To do that, we should first dismiss the myth that public speaking is just reading and talking at the same time. You already know how to read, and you already know how to talk, which is why you’re taking a class called “public speaking” and not one called “public talking” or “public reading.”

Speaking in public has more formality than talking. During a speech, you should present yourself professionally. This doesn’t necessarily mean you must wear a suit or “dress up” unless your instructor asks you to. However, it does mean making yourself presentable by being well-groomed and wearing clean, appropriate clothes. It also means being prepared to use language correctly and appropriately for the audience and the topic, to make eye contact with your audience, and to look like you know your topic very well.

While speaking has more formality than talking, it has less formality than reading. Speaking allows for flexibility, meaningful pauses, eye contact, small changes in word order, and vocal emphasis. Reading is a more or less exact replication of words on paper without the use of any nonverbal interpretation. Speaking, as you will realize if you think about excellent speakers you have seen and heard, provides a more animated message.

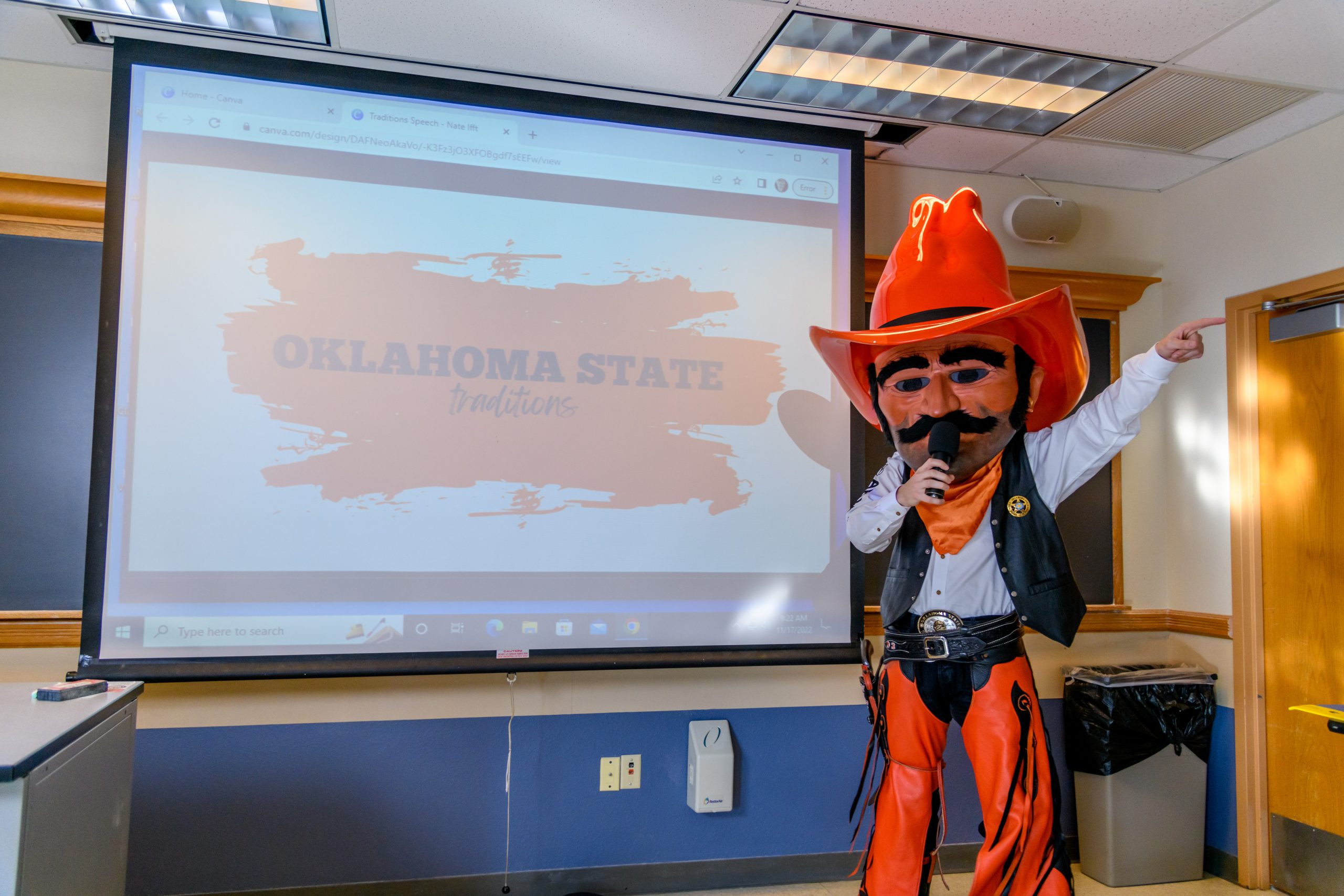

As the day of his public speaking engagement drew near, Pistol Pete found himself grappling with a common concern that many speakers face – what to do with his hands during his speech. As the spirited mascot of Oklahoma State University, Pete was well-versed in captivating audiences with his energetic presence on the field, but standing behind a podium in a formal setting felt entirely different.

With each passing day, his anxiety grew. During his practice sessions, Pete would awkwardly fidget with his hands, unsure of where to place them or how to use them effectively. He worried that his usual animated gestures might be too distracting or inappropriate for a formal speech.

Late one evening, Pete confided in a close friend, expressing his nervousness and concern about his upcoming speech. His friend, a seasoned public speaker, offered some reassuring advice. They encouraged Pete to focus on being natural and genuine, advising him to use his hands to emphasize important points and to express his passion for the topic.

Taking the advice to heart, Pete decided to rehearse his speech once more. This time, he consciously let go of his worries about his hand movements and embraced a more relaxed approach. He discovered that by using his hands to complement his words, he felt more connected to the audience and his message.

On the day of his speech, as Pete stood before the audience, he took a deep breath and reminded himself of the advice he had received. As he began to speak, he felt a newfound confidence in his gestures. He allowed his hands to express his enthusiasm, creating a natural flow that resonated with the crowd.

As the speech progressed, Pete’s worries about his hands faded away. Instead, he focused on sharing the captivating story of Frank Eaton and his legacy, letting his gestures amplify the emotions and importance of his words. In that moment, Pistol Pete realized that sometimes, the best thing to do with his hands was to let them be an extension of his authentic self, creating a genuine connection with the audience and leaving a lasting impression. How comfortable are you with using your hands effectively during a presentation?