3.2 Cognitive Theories of Learning

In the 1960s, cognitive theories of learning gradually began to replace Behaviorism as a predominant view. Cognitive theorists claim that observable behaviors are not sufficient to describe learning because the internal thought processes are also part of learning. The cognitive perspective was heavily influenced by the development of computer technology and telecommunications, and use the computer as a metaphor to understand what is happening in the human mind. Learning is defined as storing and organizing information and concepts in the mind.

Information Processing

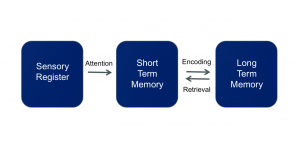

One of the early cognitive theories of learning and memory was Atkinson and Schiffrin’s (1968) Information Processing Theory. This theory views the mind as a computer that accepts inputs and performs processing activities on those inputs, similar to the way a computer processes data. In this view there are three “buckets” known as memory stores.

When you take in information—seeing, hearing, smelling, etc.—it starts in the sensory register. You are constantly bombarded with sensory information, and most of these stimuli are dropped after reaching the sensory register because you don’t pay attention to them. For example, when you are enjoying a meal in a restaurant with friends, the sound of other people’s conversations reaches your ears, but you normally do not attend to these sounds and therefore do not remember hearing them. The stimuli that you do attend to are then sent to your short-term memory. The short-term memory is where you work with information, process it, and try to pass it into long-term memory.

The theoretical terminology of Information Processing has worked its way into colloquial speech and somewhat changed in meaning. In Information Processing Theory, short-term memory is very short indeed—about 30 seconds! In order to keep something in your mind longer than that, you need to process that information. You do this by rehearsing (repeating) it, or connecting it to what you already know. Or, perhaps you create visual images. The processing you do to make the new information meaningful and memorable is called encoding. Encoding moves information from your short-term memory to your long-term memory.

When you need to remember something that you learned previously, you retrieve it from your long-term memory and move it back into your short-term memory, a process analogous to opening a file on your computer and displaying it on the desktop. This is why short-term memory is also known as working memory. (These two terms originated from different but similar theoretical models of how memory works.)

Short-term memory has a limited capacity. In his article “The Magical Number Seven,” Miller (1956) proposed that we can hold approximately seven items in our short term memory, or, taking individual variation into account, “seven plus or minus two.” There are strategies we use to help us effectively increase this capacity, however. Chunking is the process of memorizing small units so they become single items in memory. We can then hold seven plus or minus two “chunks” in our memory. An example of this would be a 10-digit phone number, which is chunked into an area code, prefix, and a final chunk of four digits. (This was more important in the days before mobile phones did our dialing for us!)

In contrast to our limited short-term memory, long-term memory is believed to be unlimited in capacity. While there is some disagreement about whether we really retain everything in long term-memory “forever,” there is agreement that we retain a large amount of information for a very long time. Often when we have trouble remembering something, the difficulty is with retrieval. Retrieval is particularly difficult for things we memorize only by rote rehearsal; a more elaborate encoding process will lead to more useful retrieval cues.

Cognitive Load Theory

Cognitive Load Theory (Sweller, 1994) elaborates on the concept of a limited short term memory by defining three types of “load” that need to be considered by instructors and instructional designers. Extraneous load is the cognitive burden posed by distracting elements. An example would be a confusing navigation process in a poorly designed tutorial. Intrinsic load is the complexity inherent in the subject matter. Dealing with that complexity is part of learning the material, and can’t be entirely avoided. Germane load is the cognitive demand of processing the subject matter. Remember that to move new information from short-term memory to long-term memory in a retrievable manner, we need to use elaboration techniques. Elaboration is effortful, however, and poses germane cognitive load. According to Cognitive Load Theory, instructors and instructional designers should seek to minimize extraneous cognitive load to free the learner’s capacity to handle the intrinsic and germane load.

Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning

Richard Mayer’s Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning is a particularly useful theory for educational technologists because it attempts to offer some prescriptive advice for designing media for learning. Let’s use multimedia to explore this multimedia theory! Watch the videos below for more information.

Good explanation of the theory in 5:24 minutes

Description of the theory and its implications; 5:27 minutes

Excellent and thorough explication: 13 minutes

This webpage also provides more detail about this theory.

Constructivism

Constructivists believe that learning occurs as an individual interacts with the environment and constructs meaning by making sense of his or her experience. While still a cognitivist theory, it emphasizes meaning-making processes that may be unique for each learner. The teacher’s role is to create experiences that facilitate this meaning-making process.

Jonassen, Peck, & Wilson (1999) define the following five attributes of meaningful learning:

- Learning is active. Learners manipulate the environment and learn from observing the natural consequences of their actions.

- Learning is constructive. Learners integrate new experience with prior knowledge to construct meaning.

- Learning is intentional. Learners articulate learning goals and reflect on the progress towards these goals.

- Learning is authentic. Learners need to experience a rich, authentic context for their meaning-making.

- Learning is cooperative. Learners construct knowledge through productive conversation with other learners.

Educational technology can facilitate a constructivist learning experience through tools such as collaborative shared documents (e.g., wikis), information for exploration (e.g., web searching), complex simulations, and constructive projects (e.g., video creation).

This resource is no cost at https://open.library.okstate.edu/foundationsofeducationaltechnology