3.1 Behaviorist Theories of Learning

In the early 1900s, the most prevalent way of looking at learning was the view we call behaviorism. Behaviorists defined learning as an observable change in behavior. At the time, this was viewed as a scientific approach, in contrast to the introspective or psychoanalytic view of learning that had been prevalent in the past. Behaviorists believed that we can never know what is going on “inside people’s heads” and that it is inappropriate to try to guess or speculate at what cannot be empirically observed. Instead, they believed that we should watch for observable changes in behavior to find out what people were learning.

Classical Conditioning

In the early part of the 20th century, Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936) was studying the digestive system of dogs when he noticed an interesting behavioral phenomenon: The dogs began to salivate when the lab technicians who normally fed them entered the room, even though the dogs had not yet received any food. Pavlov realized that the dogs were salivating because they knew they were about to be fed; the dogs had begun to associate the arrival of the technicians with the food that soon followed their appearance in the room.

With his team of researchers, Pavlov began studying this process in more detail. He conducted a series of experiments in which, over a number of trials, dogs were exposed to a sound immediately before receiving food. He systematically controlled the onset of the sound and the timing of the delivery of the food, and recorded the amount of the dogs’ salivation. Initially the dogs salivated only when they saw or smelled the food, but after several pairings of the sound and the food, the dogs began to salivate as soon as they heard the sound. Pavlov concluded that the animals had learned to associate the sound with the food that followed.

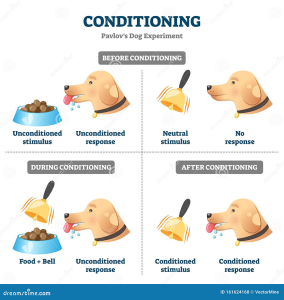

Pavlov had identified a fundamental associative learning process called classical conditioning. Classical conditioning refers to learning that occurs when a neutral stimulus (e.g., a tone) becomes associated with a stimulus (e.g., food) that naturally produces a behavior (e.g., salivation). After the association is learned, the previously neutral stimulus (e.g., a tone) is by itself sufficient to produce the behavior (e.g., salivation).

Psychologists use specific terms to identify the stimuli and the responses in classical conditioning. The unconditioned stimulus (US) is something (such as food) that triggers a natural occurring response, and the unconditioned response (UR) is the naturally occurring response (such as salivation) that follows the unconditioned stimulus. The conditioned stimulus (CS) is a neutral stimulus that, after being repeatedly presented prior to the unconditioned stimulus, evokes a similar response as the unconditioned stimulus. In Pavlov’s experiment, the sound of the tone served as the conditioned stimulus that, after learning, produced the conditioned response (CR), which is the acquired response to the formerly neutral stimulus. Note that the UR and the CR are the same behavior—in this case salivation—but they are given different names because they are produced by different stimuli (the US and the CS, respectively).

Conditioning is evolutionarily beneficial because it allows organisms to develop expectations that help them prepare for both good and bad events. Imagine, for instance, that an animal first smells a new food, eats it, and then gets sick. If the animal can learn to associate the smell (CS) with the food (US), then it will quickly learn that the food creates the negative outcome, and not eat it the next time.

Operant Conditioning

In contrast to classical conditioning, which involves involuntary responses (e.g., salivating), B.F. Skinner’s Operant Conditioning posited that learning occurs through the process of reinforcing an appropriate voluntary response to a stimulus in the environment.

Operant Conditioning has some very specific terminology. This terminology is often misused because the terms have a different meaning from their common colloquial use. Skinner claimed that the consequences that follow any given behavior could either increase or decrease that behavior. He used the term reinforcement to describe consequences that increases a behavior and punishment to describe those that decrease the behavior. He further claimed that a reinforcement or punishment could be either a stimulus added, which he defined as positive, or or a stimulus removed, which he called negative. It is important to set aside the common meanings and connotations of the words positive and negative and focus on how they are defined in Operant Conditioning. In this context the terms are more like “adding and subtracting” rather than “good and bad.”

A reinforcement, then, can be either positive or negative. For example, if you give a child praise for completing her homework (because you want her to continue this desirable behavior), you would be giving her positive reinforcement. Negative reinforcement, on the other hand, removes a consequence or stimulus that the person doesn’t like, in the hope of increasing the desirable behavior. If you tell the child that because she completed her homework immediately after school today she is excused from helping with the dinner dishes, you are giving her negative reinforcement. In both cases, you are hoping the reinforcement you provide will increase the desirable behavior of completing her homework.

The goal of punishment is to decrease a behavior. Positive punishment is an added stimulus designed to decrease a behavior. If a child is acting out in class and you scold him, you are delivering a positive punishment. The scolding is an added stimulus. A negative punishment would be taking something away that the child wants. For example, if you tell him he has to stay in from recess after acting out in class, you are using negative punishment.

The important thing to remember about reinforcement and punishment is that the result determines whether a stimulus serves as a reinforcement or a punishment, regardless of the intentions of the person delivering the stimulus. A teacher can take a certain action with the intention of punishing a child, but end up inadvertently providing reinforcement. If the child who is acting out in class craves any kind of attention she can get from an adult, both the praise and the scolding can be equally reinforcing for her.

While the examples above involve humans, it is important to note that Skinner’s research was primarily done with animals trained in special cages called “Skinner Boxes” designed to deliver reinforcements and punishments. For example, he would train a rat to push a lever when a green light came on by first watching the rat move around and explore the cage until it eventually pushed the lever. When the rat pushed the lever a food pellet would be released, which caused the rat to push the lever frequently. Once this behavior was established, he would start turning on a light, and only release a food pellet if the rat pushed the lever when the light was on. Eventually, the rat would be trained to push the lever every time the light came on.

Skinner believed that human learning occurred by the same mechanism, and that even very complex behaviors could be learned by reinforcing intermediate behaviors (as in the example of the rat above) and gradually shaping the complex behavior. In 1957, Skinner published “Verbal Behavior,” where he applied his theory to language learning. This was controversial. The linguist Noam Chomsky, for example, argued that Operant Conditioning was inadequate to explain how humans learn to construct new sentences in response to new experience.

For more information about B. F. Skinner and his Operant Conditioning theory, see this 5-minute video:

Behaviorism in Educational Technology

Today, principles of Operant Conditioning are used by teachers for general classroom management and to support students with special needs. Educational technology has also employed Behaviorist principles, especially Operant Conditioning. Programmed Instruction, for example, is a teaching strategy that developed and grew along with advances in technology. Drill and practice software is helpful for specific content, such as multiplication tables or second language vocabulary, that must be learned to a level of automaticity. Games and gamification also make use of Operant Conditioning principles. Acquiring resources and “leveling up” provide reinforcement, while losing one’s sword in a battle or falling off a cliff serve to punish errors.

This resource is no cost at https://open.library.okstate.edu/foundationsofeducationaltechnology