5 Personal Learning Networks: Defining and Building a PLN

Cathy L. Green, Oklahoma State University

Oklahoma State University

Abstract.This article answers questions about what a personal learning network is, why you might want to build one, and how to create one for yourself to experience the benefits it has to offer.

What is a Personal Learning Network?

One of the strengths of the digital environment is its highly networked nature and this is particularly relevant for personal learning networks where access to information and resources far surpasses anything that has come before both in terms of variety and volume. Further, in such an environment information changes more rapidly than ever before, and individuals need to engage in ongoing learning to keep pace, be it in a professional, personal or civic capacity. At one time it was adequate to read a daily newspaper, a magazine or two on special topics of interest and perhaps belong to an organization of interest that had conferences or meetings once or twice a year. In the past, an education typically set one up for life in the work of their choice and while there were changes in fields or topics of interest, they happened slowly, in terms of years. In the digital world of the 21st century, however, this is no longer the case and information can change in days, weeks or months. An excellent tool for handling quickly expanding and growing data is to create a Personal Learning Network (PLN) (Delaney & Redman, 2014; Perez, 2012; Trust, 2012).

PLN’s consist of formal and informal networks of individuals with similar goals and interests who interact using digital tools to share information, learn from each other, problem solve and collaborate (Ferguson, 2010; Nelson, 2012; Perez, 2012; Trust, 2012). They provide a vehicle for lifelong learning for both personal and professional development by enabling individuals to remain relevant in a world of rapidly changing information. While PLN’s can encompass both digital and face to face connections (Perez, 2012) the focus of this discussion will be on digital learning networks and why they are significant to learning in a digital age.

In addition, PLN’s provide far greater resources and information than one can muster alone or in a small group (Ross, Maninger, LaPrairie, & Sullivan, 2013). Ferguson (2010, p. 13) emphasizes this point when he says, “Before I built my professional learning network, I did all my learning by myself. If I needed to understand something for a new unit, I researched it on my own…. A PLN is a community of individuals around the world who are learning together.” Even though Ferguson specifically mentions a professional learning network, the mechanics of how the network functions is much the same as in a personal learning network, just with a different focus. The key point here is the idea of “learning together”. Within a networked environment there is less emphasis on singular sources of expertise and instead, a focus on dialogue and constructing knowledge as a group comes into play. This is facilitated by the speed with which conversations take place in a digital environment where people can connect across the globe in minutes and hours instead of weeks, months or years.

While the characteristics of a PLN include fast access to massive amounts of information, a successful PLN is also characterized by participants who are highly self-motivated and curious. Without people who have a passion for learning, a PLN would not be as valuable. Further, the ability to build one’s own network makes it possible to develop a highly customized approach to learning. As you will see, building a PLN gives one the freedom to develop tools, skills and knowledge that specifically suit one’s learning needs.

Tools for building a PLN.

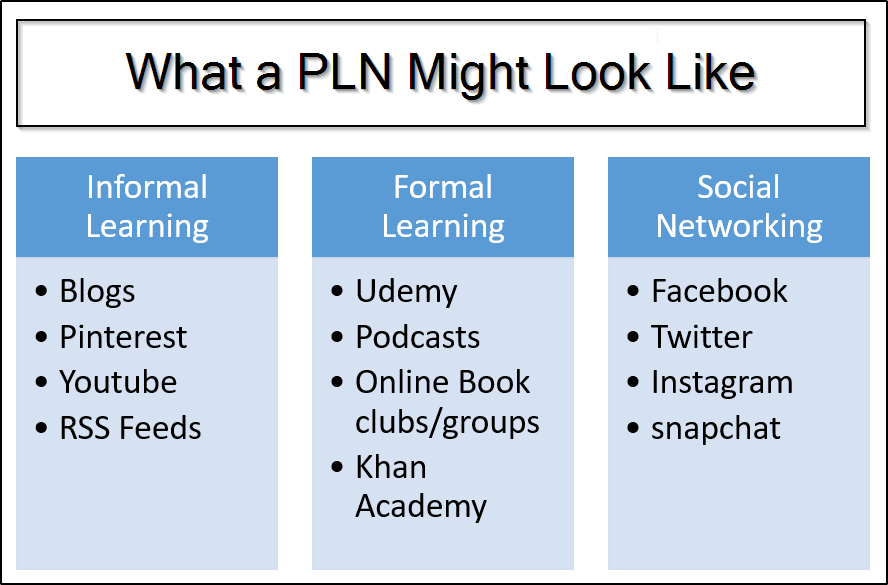

A digital PLN can reflect a variety of tools and methods, depending on individual preferences and goals. Most people will develop a variety of tools for a well-rounded learning network that meets all of their needs. An easy way to think about building a PLN is to decide what functionality you need. For example, one requirement of a PLN is to gather the information that helps one stay current with developments in a particular field or interest area. Blogs, RSS feeds, email lists, websites, news groups and podcasts can provide a steady stream of up to date information. To take advantage of the experience of a wider variety of people and practitioners, another way to connect is through social networking tools. Some are smaller and focused on a specific subject such as Edmodo, Classroom 2.0 or the Educator’s PLN while others are much bigger and provide a single tool for tracking a variety of topics and information such as Twitter, Linked-in and Pinterest. Websites such as these provide an opportunity to both share and receive new information as well as find support, collaborators and thoughtful discussions.

While informal networks and learning opportunities are a hallmark of PLN’s it is not uncommon to include formal learning tools as well. Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCS) are offered by many colleges and universities. They are free and can offer opportunities to fold new topics and information into one’s existing expertise. ITunes-U has a large selection of lectures from multiple colleges and universities and there are also a number of websites offering online classes on a variety of topics such as Udemy and Khan Academy. Even YouTube is a good bet for finding instructional information for specific skills and topics. In short, a PLN is what each individual wants it to be and it reflects each individual’s personal passions, motivations and desire to know (Moreillon, 2016; Nelson, 2012).

Figure 1. Categories of learning for a personal learning network (Green, 2017).

Figure 1. Categories of learning for a personal learning network (Green, 2017).

How to build a PLN.

Because there is such a wide variety of available tools and goals for PLN’s not everyone’s PLN will look the same. In addition, the tools for inclusion are always changing and some have different features and benefits. Given the variety of different tools available, it may be intimidating to get started so this last section offers some advice about how to start and build a successful PLN. The following can suggest a typical path towards developing a PLN.

The best way to get started is to choose a specific tool and work with it until it feels comfortable (Trust, 2012). Setting up sources for current information is a good place to start and member organizations’ websites have a lot to offer. For example, if one has an interest in world drumming and participating in drum circles, one might start the web site http://www.worldmusicdrumming.com/. They have a resources list, provide workshops, and they have a Facebook page. This is a great start and it connects me with an organization that caters to my personal interest and to a Facebook page where I will engage with other people who share my passion for drumming. Once I begin checking the Facebook page I find a really interesting post about an African song. A few clicks later I have landed on http://pancocojams.blogspot.com/ where I find a lengthy article about traditional afro-Cuban music.

At this point I have an organizational website with information that is updated maybe monthly, a Facebook page that appears to be very active with posts every day and a related blog that is also updated at least every couple of days. This is a really good start to a PLN. At some point I may decide to take a drumming class, either online or in person and that organization will likely have a web presence that I can add to my PLN. I may also decide I need some help with a specific instrument and seek out some YouTube videos on how to play it and I can create a personal YouTube channel with my favorite videos. The important things to remember are “don’t try to read everything” and spend consistent time cultivating your sources (Perez, 2012).

A final step to consider in developing a PLN is to think about contributing your own information. The one thing that makes a PLN an excellent way to learn is to contribute your own information and expertise. Without people who contribute, a PLN would stagnate quickly. Nobody wants to hang out on a Facebook page where the last post was three months ago. So, when developing a social networking presence don’t lurk, actively participate and separate the professional from the private (Perez, 2012).

Now that one has a PLN the last tip is to tend to it. Without attention and care, the PLN will not be useful and interest will wane. Think of it as a garden. Sometimes planting, sometimes weeding, sometimes harvesting but always tending the garden so that it grows and is productive. Occasionally a resource may stop being useful so remove it. Other times a new, interesting resource can be added. Whatever the decision, keep in mind that this is your PLN and it is designed to serve your needs. There are no right and wrong ways to go about it. So, as one network source grows and matures expanding to another tool or community can help fill any gaps in the first one.

Conclusion.

In setting up a PLN, variety is a key factor to success. Engaging in different communities with different areas of focus will provide a rich environment for learning. This is especially easy to do in a digital environment where one literally has the entire world to draw from as a source of inspiration. There is no need to settle for sources that do not meet your needs. In the end, the important thing is that each individual can select those tools and websites that meet their learning needs. Those will not be the same for everyone and they may change over time as well.

Additional Resources.

How to build a PLN

Characteristics of successful PLN’s

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5uoJwy3oa0I

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fAKa5tXD8Gk

References.

Delaney, S., & Redman, C. (2014). Incorporating collaborative, interactive experiences into a technology-facilitated professional learning network for pre-service science teachers. Proceedings of the International Conference E-Learning 2014 – Part of the Multi Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems, MCCSIS 2014, 369–373. Retrieved from http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-84929448306&partnerID=tZOtx3y1

Ferguson, H. (2010). Join the flock! Learning & Leading with Technology, 37(8), 12–15. Retrieved from http://www.iste.org/learn/publications/learning-leading/issues/june-july-2010/join-the-flock!

Moreillon, J. (2016). Building Your PERSONAL LEARNING NETWORK (PLN): 21st-Century School Librarians Seek Self-Regulated Professional Development Online. Knowledge Quest, 44(3), 64–69. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lih&AN=112090464&site=ehost-live

Nelson, C. J. (2012). 64 Knowledge Quest | Personal Learning Networks, 70–74.

Perez, L. (2012). Innovative professional development. Knowledge Quest, 40(3), 20–22. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.georgetowncollege.edu:2048/login?URL=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=82563981

Ross, C. R., Maninger, R. M., LaPrairie, K. N., & Sullivan, S. (2013). The Use of Twitter in the Creation of Educational Professional Learning Opportunities. Administrative Issues Journal: Connecting Education, Practice, and Research, 5(1), 55–76. https://doi.org/10.5929/2015.5.1.7

Trust, T. (2012). Professional Learning Networks Designed for Teacher Learning. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 28(4), 133–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/21532974.2012.10784693

This resource is no cost at https://open.library.okstate.edu/learninginthedigitalage/