2 Effective Instruction in Blended Learning Environments

Corrine McCabe, Central Michigan University and Raymond W. Francis, Central Michigan University

Central Michigan University

Abstract. Blended learning has become a popular term in education today. This chapter aims to explain the definition of blended learning, provide an overview of common blended learning models and offer suggested practices in designing a blended learning environment in K-12 settings. The authors also correlate blended learning practices and benefits to the Universal Design for Learning principles.

Learning Outcomes

- Define blended learning

- Investigate common blended learning models

- Explore suggested strategies for designing a blended learning environment

- Develop an understanding of the connection between blended learning and Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

What is Blended Learning?

According to Horn and Staker (2015), “Blended learning is any formal education program in which a student learns at least in part through online learning, with some element of student control over time, place, path, and/or pace” (p. 34). Blended learning environments are also commonly referred to as “hybrid” courses or classes. Any mixture of online learning and face-to-face (or traditional) settings can be classified as “blended learning.” For the purposes of this paper, the terms “blended” and “hybrid” will be used synonymously.

Learning in the digital age means learning can happen at anytime from anywhere. Therefore, blended environments are becoming more and more prevalent in the world of education. Such learning environments are typically thought of as evolving in higher education. In fact, The University of Potomac communicated that 6,700,000 students were enrolled in online courses in 2014 (2017). Additionally, Lehman and Conceição (2014) reported, “Participation in online courses has grown by 358% since 2003 (p. 4). The demand for online learning opportunities is growing and will only continue to grow as time goes on.

However, these blended learning environments are making their way down into the land of high school and elementary education. Lips (2010) reported, “As many as 1 million children (roughly 2 percent of the K-12 student population) are participating in some form of online learning” (para. 3). The learning settings include fully online as well as blended learning programs. The potential benefits of blended learning, in particular, are causing K-12 schools to take notice and explore implementation of blended learning models.

Why Blended Learning?

It is no secret that the education system of the United States is failing students. This is likely due to the fact that society is changing and the world is evolving, but the education system is the same as it was over two centuries ago. Back in the 19th century, the goal of the school system was to prepare students for jobs in factories, mills and other labor-driven employment. Hence, the development of a “factory system” of education. Students were placed in groups according to their age (without regard for learning needs or abilities). All students were taught the same thing, at the same time, in the same way as if they were on a conveyor belt. This type of education worked then because the goal was different than it is now. Now, 200 years later, the goal of the education system has changed, but the model has not. As Horn and Staker (2015) explained, “Today’s factory model of education, in which we batch students in classes and teach the same thing on the same day, is an ineffective way for most children to learn” (p. 8). School systems need to evolve into the digital age with the rest of the world, otherwise a great disservice is being done to our students. According to Lips (2010), “Online learning has the potential to revolutionize American education” (para. 22).

While the research is limited for elementary settings, the flexibility and adaptability of blended learning, or hybrid, models offers enhanced teaching and learning experiences. Prescott, Bundschuh, Kazakoff and Macaruso (2016) explained, “Blended learning can take various forms, thus allowing users to adapt a program that best fits their pedagogical goals and physical setting” (p. 1). In other words, blended learning provides teachers with the ability to personalize learning for students. In a meta-analyses of 45 studies, Means, Bakia and Murphy (2014) found that, “on average, students in conditions that included significant amounts of learning online performed better than students receiving face-to-face instruction,” and went on to state that, “the subset of the studies employing blended learning approaches was entirely responsible for the observed online advantage” (p. 20). Hence, blended learning is suggested to be more beneficial than fully online or fully traditional settings.

Means et al. (2014) suggested several reasons or purposes for the implementation of blended learning in relation to K-12 schools which include the following:

- Accessibility of learning

- Facilitation of small group instruction

- Addressing diverse needs

- Increase in productivity

- Providing a variety of instructional methods and techniques

- Enhancing engagement among students and teachers

- Providing additional support for complicated, abstract content

As explained by Horn and Staker (2015), “Blended learning is the engine that can power personalized and competency-based learning” (p. 10). Furthermore, “It provides a simple way for students to take different paths toward a common destination,” and, “It can free up teachers to become learning designers, mentors, facilitators, tutors, evaluators, and counselors to reach each student in ways never before possible” (Horn & Staker, 2015, p. 10-11).

Blended Learning Models

There are many ways in which blended learning has been implemented. As more is learned about the effectiveness of hybrid learning environments, one can postulate that more models will be developed. For now, the following models will be discussed: rotation models, a flipped model, flex and “a la carte” models, an enriched virtual model, and a mixture or blend of models.

Rotation Model

The rotation model is the most common model of blended learning used by elementary school teachers. In today’s classrooms, many teachers already use a rotation model in an effort to provide small group instruction. Common in elementary schools is the use of the Daily 5, which is a framework for structuring literacy time in the classroom. It consists of various activities designed to teach students independence while engaging in meaningful literacy tasks (Boushey & Moser, 2014). Rotation models are not new to the K-5 setting but are less utilized (out of blended learning context) in middle- and high-school.

Station Rotation. Specific to blended learning, station rotation includes groups of students rotating through learning stations, at least one of which would include an online learning component (see Figure 1). Depending upon the content area and the teacher, this may look different in every classroom or school. Typically, students are grouped by need or ability. The group moves through various stations together (the number of stations depends on the way the teacher set up the class). Suggested stations may include small group instruction with the teacher (the face-to-face component), individual learning (self-paced and online) and independent practice or application (may be an online task or traditional task).

Lab Rotation. For schools which are not yet 1:1, meaning not every student has his or her own device to use, a lab rotation might be the only option (see Figure 2). The lab rotation is set up similar to station rotation, but involves students moving to a computer lab, facilitated by staff other than certified teachers (i.e. aides, paraprofessionals, support personnel) somewhere else in the school. A percentage of students’ day is spent in the computer lab focused on basic skills through the use of software or other online materials deemed appropriate by the school district or teacher.

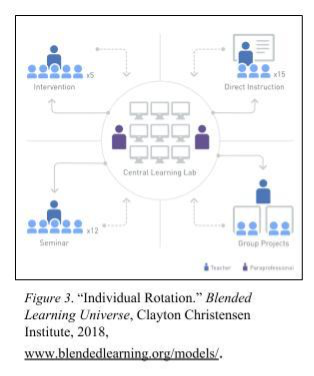

Individual Rotation. In this model, algorithms are used to design students’ rotation schedule based on their assessment scores. They may still encounter the similar educational experiences, but the prescribed rotation schedule is based on their personal needs (see Figure 3). Horn and Staker (2015) explained the individual rotation as, “Each student has an individualized playlist to guide him through the rotations. Paraprofessionals are on hand to assist students with Edgenuity [online curriculum]. In the breakout rooms, a face-to-face teacher expands on the material introduced online and helps students apply it” (p. 45). The factor that sets this model apart from the other rotation models is that students transition individually rather than with a group of students.

Flipped Classroom

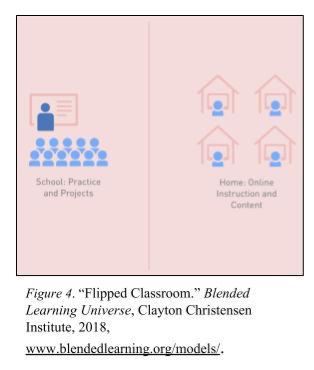

The flipped classroom model flips the setting of traditional learning (see Figure 4). In this model, students do the “learning” at home via online tools, such as instructional videos, recorded lectures, and other content-related material. The teacher then uses the traditional face-to-face time to help student apply what they have learned through higher-level tasks, projects and assignments. This model lends itself to the middle school and high school settings where time is extremely valuable, and often limited.

Flex Model

Originally designed to provide an opportunity for high school dropouts to recover education credits, the flex model offers students an opportunity to set their own schedules. In the flex model of blended learning, online instruction and online delivery of content is the main mode of student learning (see Figure 5). Teachers, in this model of blended learning, design the course, but then act as more of a facilitator and are used “as-needed.” Learning is student-driven and self-paced in this model which is much more likely to be used in a high school or higher education setting.

A La Carte Model

The “A La Carte” model offers students a chance to take a fully online course on top of their traditional course schedule (see Figure 6). This type of model is seen more often in high school and higher education settings because if provides students with an opportunity to move more quickly through their program. As more colleges and universities are offering this option, the high schools are doing the same to make sure their students are fully prepared for higher education.

Enriched Virtual Model

As explained by Horn and Staker, “Many Enriched Virtual programs began as full-time online schools and then, noticing that their students needed more support, developed blended programs to provide face-to-face enrichment and a safe, peaceful physical setting” (p. 50). However, the traditional classes do not meet daily, or even regularly. Often times, courses implementing an Enriched Virtual model use the progress of the students to determine how often they provide traditional face-to-face instruction or support. That being said, this model lends itself to the higher education setting and is not ideal for K-12 schools (see Figure 7).

Mixture of Models

While the models of blended learning described above are the most common, it is not uncommon to see a blend of models evolving in classrooms. For example, an elementary school teacher might use a “station rotation” model, but “flip” his or her whole group instruction to make efficient use of his or her time with students. The bottom line is that as students continue to evolve and the goal of education continues to evolve, so will best practices in education.

Designing a Blended Experience

Designing an effective blended learning experience is not as easy as just taking traditional content and making it available online. Means et al., (2014) cautioned that the benefits of online learning, “tended to result from a redesign of instruction to extend learning time or promote greater engagement with content” (p. 23). In addition, they explained that such positive outcomes were a result of blended learning environments which, “were likely to involve additional instructional resources and activities that encouraged interactions among learners” (Means et al., 2014, p. 23). Furthermore, Lehman and Conceição (2014) suggest the use of “intentional design” which they explained as, “a method that involves purposeful action and takes into consideration the online learning environment, the teaching process, and learner characteristics” (p. 19).

Community & Culture

One of the most important factors to consider in designing a blended learning experience for students is establishing a community and culture of learning and growing. Establishing a sense of community in a traditional classroom is much easier to do than in an online environment. BlendedLearning.org shed light on this important factor by stating, “Culture is especially useful—or toxic—in blended programs because blended learning goes hand in hand with giving students more control and flexibility. If students lack the processes and cultural norms to handle that agency, the shift toward a personalized environment can backfire” (Clayton Christensen Institute, 2018). Teachers must be very intentional with their course design to include components of interaction and collaboration amongst online students. In the field of blended learning, a teacher should ensure that the culture he or she sets up within the traditional setting is upheld in the online setting as well.

Delgado, Wardlow, McKnight and O’Malley (2015) dittoed the need for establishing a culture of learning. They suggested, “Fostering a learning culture means shifting a traditional teacher-centered model to a student-centered model,” which allows the students to drive their own learning while the teacher is available to provide personalized direct instruction to a small group of students or one-on-one (p. 403). Poirier (2010) provided the following suggestions for instructional strategies which can help establish a culture of collaboration and learning:

- Encourage student leadership in online discussions through assignment of roles

- Integrate ice breakers and scavenger hunts when introducing a new topic

- Use team-based jigsaw presentations to review content

- Ask students to submit photos with their introductions

- Require students to create and maintain a digital portfolio and provide links for the rest of the students to view

Motivation & Engagement

Francis (2012) pointed out that, “Simple class size and access to technology can lead to students having a greater opportunity to be off-task and disengaged in the classroom” (p. 147). This can happen in blended learning environments as well, even with the teacher in the same room. When building a blended learning experience or hybrid course, engagement and motivation are crucial to the success of students regardless of their age.

Andrew Miller, an experienced online teacher of K-12 students, has experienced the challenges of motivating and engaging his students. Through his experiences, Miller (2012) found that, “If you want students to be engaged…it [the activities] must be meaningful” (para. 3). In order for learning activities to be meaningful, they must have purpose.

Whether in an online or a traditional classroom setting, purpose is a driving force behind engagement and motivation. Boushey and Moser (2014) explained, “Setting a purpose and creating a sense of urgency establishes a culture in which every moment of learning and practicing counts” (p. 37). When teachers clearly establish the reason behind an activity, online or in-person, and the students feel the sense of urgency and usefulness, teachers and students will work together to succeed. Kelly (2012) further explained the need for students to understand the relevance of the activities or the content embedded in online learning. Teachers can ensure students understanding by, “being explicit about how the skills and knowledge students acquire in the course can be applied beyond school” (para. 5).

In addition to understanding the usefulness of coursework, Kelly (2012) indicated that students need to feel empowered. “Students feel empowered when they feel that they have some control over some aspects of their learning” (para. 3). One way to provide students with this sense of empowerment is through providing choices. In fact, Boushey and Moser (2014) use this concept in the Daily 5 framework. Based on the work of Gambrell (as cited by Boushey & Moser, 2014), “Choice has been identified as a powerful force that allows students to take ownership and responsibility for their learning. Studies indicate that motivation increases when students have opportunities to make choices about what they learn and when they believe they have some autonomy or control over their own learning” (p. 25). In sum, purpose and choice equate to motivation and engagement.

Content & Organization

One of the major benefits of digital learning is utilizing online formats to access and use up-to-date, current content. In addition, “[blended learning] enables bringing the affordances of technology to bear in teaching conceptually challenging abstract and complex content” (Means, Bakia & Murphy, 2014, p. 115). Supplemental resources, including instructional videos and other interactive media, are readily available online allowing instructors to vary the way they present new and difficult concepts to their students. Pearson Education (2016) pointed out, “Next generation instructional systems that include print and digital options with online adaptive skill building allow teachers and students to personalize in new and exciting ways” (Pearson Education, Inc., 2016).

Finding ways to present curricular content to students is only half the battle. Teachers also need to organize the content in a manageable way. Many online learning platforms have organizational tools available to instructors, such as timelines, modules and units. Many instructors choose to set up the online component of the class in a module format. Doing so breaks the content down into more manageable chunks. Using a modular format also allows students to plan their time and set goals. Lehman and Conceição (2014) explained that using modular (or “chunking”) techniques, “helped the students reduce cognitive overload and allowed them to focus on the content without becoming overwhelmed” (p. 24).

Assessment

With an online component embedded in traditional instruction, digital tools to create assessments which provide immediate feedback are more prevalent. Additionally, teachers are exploring the many ways in which students can demonstrate their learning beyond the multiple-choice assessments of the past. Access to digital devices with internet access enables students to “show what they know” in a multitude of ways which were impossible before, including: recording an audio or video response using tools like Recap or FlipGrid, making an interactive presentation using Nearpod, collaborate on a project using Google Docs or Google Slides, create a website or a blog, etc.

Communication

Another key component in designing online learning environments is communication. Clear communication of expectations and learning intentions, success criteria and learning progressions are essential for student success in online learning. Waack (n.d.) summarized John Hattie’s work regarding teacher clarity with the following statement, “Clear learning intentions describe the skills, knowledge, attitudes and values that the student needs to learn.” The criteria for success should also be clear and concise. Students need to know what they need to do in order to be successful. Sharing the progression of learning allows students to understand how content builds throughout the course or class. Doing these things provides students with a sense of organization and time management allowing students to pace themselves, which will in turn keep them motivated and engaged. Lehman and Conceição (2014) provided a few clear guidelines for this task:

- Provide specific course outcomes

- Include explicit directions for assignments and tasks

- Share the goals of the course or class

- Use deadlines or due dates (p. 25-26)

In addition to the above suggestions, it is also important to provide consistent and specific feedback to students throughout the blended experience. This might be done through chats, email, and/or commenting tools. Lehman and Conceição (2014) reported, “Consistent feedback made students feel self-confident and provided them with a consistent pace” (p. 29). Lack of feedback can often have negative effects on the learning environment, whether online or in-person. In a meta-analysis of educational studies, Hattie and Timperley (2007) found that, “Feedback is among the most critical influences on student learning” (p. 102).

Personalized Learning

“The opportunity to help every student learn at the best pace and path for them is the most important benefit of digital learning” (Pearson Education, Inc., 2016). In order to do this, instructors must start by getting to know their students and their students’ interests. This can be achieved through interest-surveys, informal chat sessions, and icebreaker activities (all can be done online or face-to-face). In addition to understanding students’ interests, it is also important to be proactive about students’ needs. One of the benefits to online courses or classes is that it reaches mores students. However, with more students come more diverse needs. It is important that instructors take into account their students’ learning needs and find ways to address the needs through the presentation of the content, the learning activities and the ways in which students demonstrate their understanding.

Universal Design for Learning

According to Coy, Marino and Serianni (2014), the demand for virtual learning environments is growing (p.64). With that growth comes more students with more needs. It is the instructor’s responsibility to consider the needs of all students as he or she designs an online learning environment. Many of the instructional strategies discussed above can be addressed through using Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles. Developed by Meyer and Rose, “Universal design for learning (UDL) is a framework to improve and optimize teaching and learning for all people based on scientific insights into how humans learn” (Cast.org, 2014). Typically, when one hears the term UDL, he or she automatically thinks in terms of special education and assistive technology. However, UDL is actually focused on meeting the needs of all learners, using strong pedagogy (in online or traditional settings), and using high-quality, research-based instructional practices. “UDL guidelines offer a set of concrete suggestions that can be applied to any discipline or domain to ensure that all learners can access and participate in meaningful, challenging learning opportunities,” and these guidelines are ever-evolving as scientists learn more about how people learn (Cast.org, 2014). The UDL principles include providing multiple means of engagement, representation and expression.

Providing “multiple means of engagement” refers to the “why” of learning. This includes using a variety of engagement techniques which may include providing options for “recruiting interest, sustaining effort and persistence, and self-regulation” (Cast.org, 2014). In an online environment, strategies might entail:

- Collaborating with students to set a vision or goal and purpose

- Providing multiple paths to reach the same learning outcome

- Creating self-reflection and self-assessment tools

- Having students predict outcomes on assignments or tests

Regardless of the strategies used, the ultimate goal of providing multiple means of engagement is to create a sense of purpose and motivation for all students (Cast.org, 2014).

The next principle of the UDL framework is to “provide multiple means of representation” which refers to the “what” of learning. This is about the presentation of the curricular content. It is important to provide options for “perception, language and symbols, and comprehension” (Cast.org, 2014). When designing any online content, an instructor might think about:

- Minimizing distractions on an educational video by using SafeShare.tv

- Using closed-captioning on instructional videos

- Paying attention to the use of distracting fonts and colors in presentations

- Using infographics or other media in addition to text

- Providing outlines of important ideas in complicated content

These strategies are important in the online learning setting, but also in the traditional classroom as the goal of providing multiple means of representation is to create “resourceful and knowledgeable” students (Cast.org, 2014). The use of technology makes this easier for teachers.

Finally, the third principle of UDL is to provide “multiple means of expression” which addresses the “how” of learning. This principle focuses on the responsibility of teachers to provide options for “physical action, expression and communication, and executive functions” (Cast.org, 2014). Strategies for addressing these concepts may include:

- Providing multiple ways to access content and material (interactive e-books)

- Allowing students to respond in various ways (audio, video, drawing, etc.)

- Using scaffolding techniques when reading and writing

- Using interactive web tools (annotation software, storyboards, etc.)

Cast.org stressed, “It is important to provide alternative modalities for expression, both to the level the playing field among learners and to allow the learner to appropriately (or easily) express knowledge, ideas and concepts in the learning environment” (2014).

UDL is an instructional framework which uses best pedagogical practices, regardless of environment; however, the use of technology makes using UDL techniques easier for teachers and students. It requires a shift in pedagogy in an effort to reach all learners despite their academic (or social) needs.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Lehman and Conceição (2014) explained that, “content design needs to be developed differently depending on the discipline and the desired outcomes of a specific course” (p. 20). Furthermore, “This process requires intention, anticipation, prioritization, and envisioning” (Lehman & Conceição, 2014, p. 20). Although the research is limited, “Blending online instruction with teacher-led activities can enable better learning when it provides a unique, new capability that supports the processes of learning, and when it increases the amount of time during which students are actively engaged in learning” (Means et al., 2014, p. 120).

As society continues to move away from the traditional factory model of education and into learning in the digital age, blended learning offers “the best of both worlds.” Benefits of blended learning models typically include: differentiated instruction, more effective use of instructional time, use of multimedia to enhance teaching and learning, personalized learning paths addressing specific learner needs, targeted instruction opportunities, increased motivation and engagement.

However, to reap these benefits, schools must consider several important pedagogical factors in their quest to set up an effective blended learning environment; such components include building a community and fostering a positive culture, using strategies to establish and maintain motivation and engagement among students (and teachers), practicing effective communication with teacher clarity and effective feedback, personalize learning for students and incorporate principles of UDL in an effort to reach all learners. Delgado et al. (2015) reported that, “blended learning could be better than traditional classrooms, when instructors’ involvement, interaction, content, student capabilities, and the right amount of human to technology [are] combined” (p. 403).

Questions to Consider

- How do the authors define Blended Learning?

- How does the author’s definition compare and contrast with your existing definition of Blended Learning?

- From your experiences, how has learning Blended Learning been a part of your learning experiences, and where could it have fit in a seamless manner?

- The rotation models of instruction provide a variety of opportunities for experience and learning through digital and blended means. How do you see any of the rotation models best fitting with your personal knowledge base and instructional style?

- Where might a mixed-model of methods best fit for student learning in digital settings? Provide a rationale for your response.

- Considering the key elements of digital learning through a Blended Learning format provided in the chapter, develop a learning opportunity to use the key elements of Blended Learning from the chapter. Provide a description of the elements you included and the ways they contributed to the learning opportunity.

References

Blended Learning Models. (2018). Retrieved April 21, 2018, from https://www.blendedlearning.org/models/

Boushey, G., & Moser, J. (2014). The daily 5: fostering literacy independence in the elementary grades (2nd ed.). Stenhouse Publishers. Retrieved from https://www.stenhouse.com/content/daily-5-second-edition?r=d52a

Coy, K., Marino, M. T., & Serianni, B. (2014). Using Universal Design for Learning in Synchronous Online Instruction. Journal of Special Education Technology, 29(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/016264341402900105

Delgado, A. J., Wardlow, L., Mcknight, K., & O’Malley, K. (2015). Educational Technology: A Review of the Integration, Resources, and Effectiveness of Technology in K-12 Classrooms. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 14, 397–416.

Digital Learning Defined. (n.d.). Retrieved April 22, 2018, from https://www.pearson.com/us/prek-12/why-choose-pearson/thought-leadership/online-blended-learning/digital-learning.html

Five Factors that Affect Online Student Motivation. (2012, August 10). Retrieved April 22, 2018, from https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/online-education/five-factors-that-affect-online-student-motivation/

Flipgrid. Ignite Classroom Discussion. (n.d.). Retrieved April 22, 2018, from https://info.flipgrid.com/

Francis, R. W. (2012). Engaged: Making Large Classes Feel Small through Blended Learning Instructional Strategies that Promote Increased Student Performance. Journal of College Teaching & Learning, 9(2), 147–152. https://doi.org/10.19030/tlc.v9i2.6910

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The Power of Feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

8 Reasons You Need Online-Learning [Infographic] (2016). Retrieved from https://www.pearson.com/content/dam/one-dot-com/one-dot-com/us/en/pearson-ed/downloads/Infographic_8ReasonsYouNeedOnline-Learning.pdf

Horn, M. B., & Staker, H. (2014). Blended: Using disruptive innovation to improve schools (1st ed.). Josey-Bass.

Lehman, R., & Conceicao, S. (2014). Motivating and Retaining Online Students: Research-Based Strategies That Work (1st ed.). Josey-Bass.

Lips, D. (n.d.). How Online Learning Is Revolutionizing K-12 Education and Benefiting Students. Retrieved April 21, 2018, from https://www.heritage.org/technology/report/how-online-learning-revolutionizing-k-12-education-and-benefiting-students

Means, B., Bakia, M., & Murphy, R. (2014). Learning Online: What Research Tells Us About Whether, When and How (1 edition). New York: Routledge.

Miller, A. (n.d.). Blended Learning: Strategies for Engagement. Retrieved April 22, 2018, from https://www.edutopia.org/blog/blended-learning-engagement-strategies-andrew-miller

Blended Learning Models (n.d.). Blended Learning Universe. Retrieved April 21, 2018, from https://www.blendedlearning.org/models/

Nearpod – Create, Engage, Assess through Mobile Devices. (n.d.). Retrieved April 22, 2018, from https://nearpod.com/

Online Classes vs. Traditional Classes – A Learning Comparison. (n.d.). Retrieved April 21, 2018, from https://potomac.edu/learning/online-learning-vs-traditional-learning/

Poirier, S. (2011). A Hybrid Course Design: The Best of Both Educational Worlds. Techniques: Connecting Education and Careers, 85(6), 28–30.

Prescott, J. E., Bundschuh, K., Kazakoff, E. R., & Macaruso, P. (2017). Elementary school–wide implementation of a blended learning program for reading intervention. The Journal of Educational Research, 0(0), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2017.1302914

Recap. (n.d.). Retrieved April 22, 2018, from https://letsrecap.com/

Rogers-Shaw, C., Carr-Chellman, D., & Choi, J. (2018). Universal Design for Learning: Guidelines for Accessible Online Instruction. Adult Learning, 29(1), 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1045159517735530

Safeshare.tv – The safest way to share YouTube and Vimeo videos. (n.d.). Retrieved April 22, 2018, from https://safeshare.tv

Shift to Digital [Infographic] (2016). Retrieved from https://www.pearson.com/content/dam/one-dot-com/one-dot-com/us/en/pearson-ed/downloads/ShiftToDigitalInfographic.pdf

Waack, S. (n.d.). Glossary of Hattie’s influences on student achievement. Retrieved April 1, 2018, from https://visible-learning.org/glossary/

This resource is no cost at https://open.library.okstate.edu/learninginthedigitalage/

Links checked 6.12.24 KE