11 Literacy in the Digital Age: From traditional to Digital to Mobile Digital Literacies

Tutaleni I. Asino; Kushal Jha; and Oluwafikayo Adewumi

Oklahoma State University

Introduction

Literacy is an enigma. While it is easy to agree that everyone should be literate, the conversation around what being literate looks like, and what the term itself is even means depends much on who is leading the conversation and who has a stake in the conversation. The term itself has historically been defined as “possession of the complementary mental technologies of reading and writing, literacy is not only difficult to define in individuals and delimit within societies, but it is also charged with emotional and political meaning” (pg. 12). This perceived simplicity has at times led to many including news reporters and various academic scholars to refer “to whole societies as “illiterate and uncivilized” as a single referent, and “illiterate” is still a term which carries a negative connotation” (Wagner (1991, pg. 12). Of course, such characterization, although still rampant, they are at least being questioned. At last literacy is being considered much more widely, and being recognised as integral to a culture where it is embedded with functions and meanings.

Literacy can be challenging to define. When narrowly defined crucial elements are left off and when stated too broadly it can be a catch-all term. This chapter does not purport to present a definition of literacy, for such a task has been undertaken and explained by many (Buckingham 1993; Knobel & Healy, 1998; Burniske, 2000 Cope and Kalantzis, 2000; & Semali 2002) who are much better versed in the subject. The goal in this chapter is to look at the understanding of digital literacy and whether or not it is (it broad enough to include the features of) inclusive enough to account for the affordance of mobile devices. Affordance in this context, can mean providing an opportunity that allows an individual to learn or perform a specific action or ability by using a mobile device. Features like portability and individuality are playing a significant role in enhancing mobile digital literacies. These features give any individual the flexibility to learn whenever they want and wherever they want (Sunga et. al, 2015). Inclusiveness is used as a reference to considering a wide range of diverse human factors, i.e., every user is entitled to participation, content creation, and giving a response, which extends beyond reading, writing or any barrier (Kirisci et. al, 2012).

Evolution of Literacy

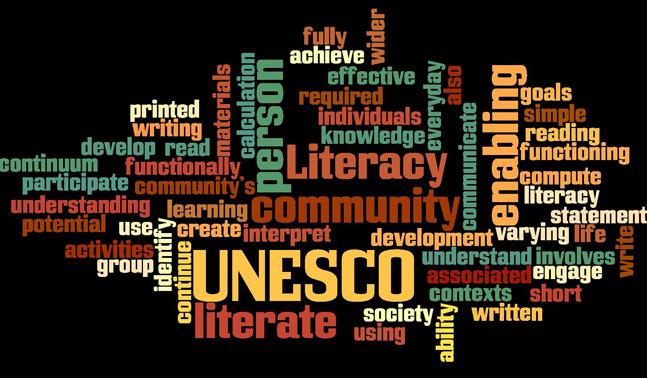

The term literacy itself has undergone numerous evolutions. Figure 1 below illustrates the different components that made up the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), definitions from 1958 – 2005.

Figure 1: UNESCO literacy keyword

UNESCO works continuously to promote inclusive education practices that eliminate the obstacles limiting the participation and success of all learners, respect the needs of people from different backgrounds and help to eliminate all kinds of discrimination in the learning environment. To illustrate the transformation of literacy Ahmed (2011), collected definitions that depict how UNESCO has changed their understanding over time. As cited by Ahmed (2011), over the decades, UNESCO has provided the following definition at different times between 1958 and 2005:

- A person is literate who can, with understanding, both read and write a short simple statement on his or her everyday life (UNESCO 1958);

- A person is functionally literate who can engage in all those activities in which literacy is required for effective functioning of his or her group and community and also for enabling him or her to continue to use reading, writing and calculation for his or her own and the community’s development (UNESCO 1978);

- Literacy is the ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate and compute using printed and written materials associated with varying contexts. Literacy involves a continuum of learning in enabling individuals to achieve his or her goals, develop his or her knowledge and potential, and participate fully in community and wider society (UNESCO 2005). (pg. 181)

The countries that have membership in UNESCO have also adopted similar stances on defining literacy and as such have had to adjust their definitions accordingly. The table below presents a random sample of countries and their definition of literacy. UNESCO has the information below available on their website from 1975 to 2010. The data was combined in an excel file and each item given a random ID which was used to create the table below. As evident, the definition of literacy has changed over time, and in alignment with the definitions provided by UNESCO.

Table 1: National literacy definitions by year

|

Country |

Year |

Literacy Definition |

|

Rwanda |

1978 |

A person is defined as literate if he or she can, with understanding, both read and write a short, simple statement on his or her everyday life |

|

Argentina |

1980 |

A person is defined as literate if he or she can, with understanding, both read and write a short, simple statement on his or her everyday life |

|

India |

1981 |

A person is defined as literate if he or she can, with understanding, both read and write a short, simple statement on his or her everyday life |

|

Lithuania |

1989 |

A person is defined as literate if he or she can, with understanding, both read and write a short, simple statement on his or her everyday life |

|

Ukraine |

2001 |

A person who has any level of education or can read (for 6 year old people and older) |

|

Liberia |

2004 |

A person is defined as literate if he or she can, with understanding, both read and write a short, simple statement on his or her everyday life. |

|

South Africa |

2007 |

Household member can read and write in at least one language. If a person can only read or only write, that person is considered illiterate. |

|

Benin |

2009 |

A person is literate who can, with understanding, both read and write a short simple statement on his or her everyday life |

|

Chile |

2009 |

Able to read and write. The population with 2 or more years of schooling is considered. |

|

Uganda |

2010 |

Able to read and write with understanding in any language |

Source: UNESCO (http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/ED/GMR/pdf/gmr2009/EFA_Literacy_metadata_2009.pdf

The three definitions from UNESCO and the definitions by the countries above, show that literacy has undergone various transformations. They’ve ranged primarily from the reading and writing paradigm to now the inclusion of electronic media and communication. Smyth (2011) opined that literacy has evolved, it has gone beyond the mastery of the ability to read and write a language but now the comprehension and how to use technology as a medium and not the mastery of technical language.

The move to include technology into the definition of literacy is undoubtedly due to the integration of Information Communication Technologies (ICTs) into everyday life. This integration and usage has brought about the information age, which is characterized by “the widespread proliferation of emerging information and communication technologies and the capabilities that those technologies provide and will provide humankind to overcome the barriers imposed on communications by time, distance, and location and the limits and constraints inherent in human capacities to process information and make decisions. Advocates of the concept of the Information Age maintain that we have embarked on a journey in which information and communications will become the dominant forces in defining and shaping human actions, interactions, activities, and institutions” (Alberts 7 Papp, 1997, pg. 2).

The information age has brought with it a new literacy referred to as digital literacy. In staying loyal to the trunk from which it sprouts, the term digital literacy has proven to be as elusive in its definition. Most definitions closely resemble that put forth by the United States, Federal Communications Commission (FCC) which argues that “. . . digital literacy generally refers to a variety of skills associated with using ICT (information and communication technologies) to find, evaluate, create and communicate information. It is the sum of the technical skills and cognitive skills people employ to use computers to retrieve information, interpret what they find and judge the quality of that information. It also includes the ability to communicate and collaborate using the Internet—through blogs, self-published documents and presentations and collaborative social networking platforms” (as cited by Clark & Visser, 2011, pg. 38).

This definition although seemingly a catchall and somewhat nebulous, still does not mention or reference the growth of mobile devices and the role that they are playing in society. Mobile devices evolved from what only the learned operated to a user-friendly device; it is not surprising that its price is beginning to decrease in emerging markets, pr items from being expensive luxuries (GMCA, 2017). The definition seems to also ignore the role mobile devices have in globalization which is not to be underestimated especially since such devices have grown beyond simple miniature computers that enable the transmission of the human voice to being content creation, delivery and consumption systems (Collins, 2005).

The definition of mobile digital literacy has grown over time due to technological advancement. An individual has become more reliant on mobile phones as compared to someone who was using it ten years back. In 1973, when a mobile phone was introduced, it was solely used for communication, mobile literacy meant being able to use the feature limited to the capability of dialing phone numbers to call someone. Today, that definition of mobile literacy can be seen in a new light with the incessant upgrades in the features. It can now be defined as the capability of using and exercising the wide array of features and applications in a personalized manner.

The growth of mobile devices to seemingly ubiquitous levels is affecting communities around the world, altering the ways we communicate, educate, collaborate and engage with one another; altering what we know or think we know about our identity and the very sense we have of space and time (Traxler, 2008). This development which in many ways is akin to Khuns’s (1962) paradigm shift theory of science necessitates an evaluation of the current models of literacies and more specifically digital literacies in which mobile devices seem to belong. As Clancy & Lowrie (2002), argued for new approaches and models to understand literacies brought about by the digital age, I am similarly arguing that the digital age has evolved beyond what it was at the turn of the century or even five years ago and as such the understanding of digital literacies need to be updated to address the new mobile digital era.

Why the update

There is an interaction between mobile devices & traditional understanding of literacy. Whereas traditional literacy was more concerned with reading and writing, mobile devices afford even those without the ability to read or write a chance to participate in the conversation. Some do this by the voice features of the technology others can do so by memorizing various patterns of the device they own, which thereby allow them to conduct business and communicate with others even though they cannot tell a difference between a 6 and a 9, yet they are able to dial it without a problem.

Mobile devices are changing how people are learning. According to Telecomlead, an online B2B publication dedicated to the telecom industry, as of Feb 2019, 89 percent of India’s population are active mobile users. However, the literacy rate of India is often cited to be at 71.20%. Even though more than 89 percent of the Indian population has a mobile phone, it does not mean that the percentage of mobile literate in India is limited to 89 percent who own a smartphone. In fact, the number of mobile literacy rates can be higher than the number of people who actually own a device. To elaborate further, let’s look at an experiment “Hole-in-the-wall” conducted by Dr. Sugata Mitra in 1999 in India to check the effectiveness of digital literacy. Dr. Mitra’s team carved a “hole in the wall to append the slum in Kalkaji, New Delhi to the NIIT premises. A free accessible computer was set up as a learning station for the people living in the slums, especially the children. The children, who now had access to the device, self-taught themselves the skill to operate the computer without prior knowledge or experience. This experiment establishes the point that one does not have to have only the ability to read or write to be considered literate. Nor does one need to go to a formal educational institution to be digitally literate, but to be able to read and write one often needs to go through some sort of formal schooling. Viewed in the context of this paper, similarly, one does not need to only be able to read or write to be considered mobile digital literate. In fact, a person without the ability to read or write can still use a mobile device to accomplish their tasks. a mobile device in order to qualify for Mobile Digital Literacy.

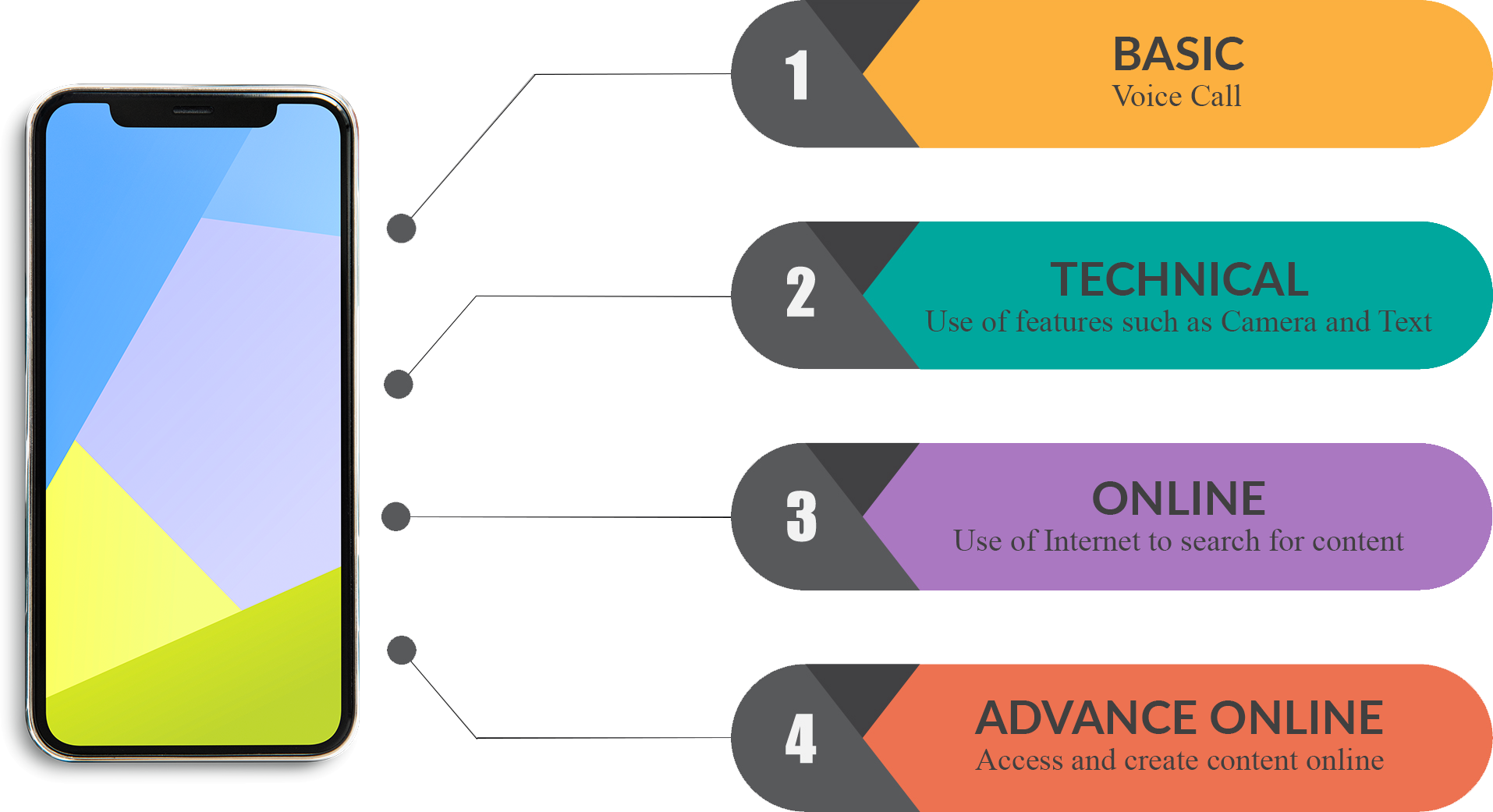

Figure 1. Stages of mobile digital literacies

Mobile Digital Literacies has four stages. These stages help to determine how literate an individual is in terms of using a mobile phone.

Basic: The basic digital mobile literacies mean a person can use their voice to communicate using mobile devices. For example, if a person is able to make a phone call to another they can be considered to have basic digital mobile literacy skills. One does not need to know how to read and write in this context, because since many mobile phones have the ability to store favourite numbers or speed dial, an individual can simply press one number and be able to communicate.

Technical: Mobile devices come with many features such as cameras and the ability to send multimedia messages. The ability to use mobile features such as sending the text, camera, calendar and calculator go beyond one’s ability to simply read and write. Such skills classify the user as a technical mobile digital literate.

Online Digital Literacy: Most mobile devices have the ability to connect to the internet. This connectivity aspect is what makes the devices so appealing to many. However, the presence of connectivity does not necessarily mean someone knows how to use the devices to complete tasks online. Hence, mobile online digital literates are those who can easily browse and search for content using different mobile applications and internet browsers.

Advance Online Literate: Lastly, advanced mobile online literates are capable enough to access, create, navigate and understand online content on a range of digital devices (GSMA, 2015). They not only have the abilities referenced in the previous stages but can also make use of the information for advance decision making.

Mobile Digital Literacies

We propose moving to adopt a new term, Mobile Digital Literacies (MDLS), which is concerned with the role mobile devices play in the world of digital literacy. Mobile Digital Literacies (MDLS) can be defined as an individual’s ability to identify, understand, interpret, create and communicate using the features and functionality of a mobile phone. It also serves an opportunity to create an identity and bring more people into the dialogue by allowing those often left out of the conversation a chance to create, recreate and reclaim their identities.

This re-imagining of digital literacy is more important because definitions, teachings and understandings of digital literacy have framed the conversation primarily “as the investigation of ways of dealing with the computer and the Internet” (Pietrass, 2007, pg. 8), which does not include new technologies.

This positioning of digital literacy or new literacies as something that someone else does that students have to examine critically does not go far enough to capture the effects of mobile devices on society and limits our ability, therefore, fall short at providing a framework to critically look at the phenomenon. The issue is no longer simply about the effect of available information but rather the effect of the information one creates.

Many people, especially those born in the 1990s to today have most of their life digitally recorded. They saw the evolution of many digital platforms firsthand, which includes mobile devices as well. They can easily adapt to the options and in turn, help the new age population to adapt to the options as well. In Born Digital, Palfrey & Gasser (2008) discuss ways to understand those born in the digital age and also cover the term Digital Dossier which they attribute to Daniel J. Solove, a professor of law at the George Washington University Law School (p. 301). The definition of digital dossiers is that, today even before a person is born today, their digital identity starts being constructed through things such as prenatal exams that a mother goes to, and ultrasound images from doctor visits. Even before a child is outside its mother’s womb, his or her picture has possibly already been on the Internet if the parents decided to share the picture of the ultrasound. This life cycle continues with doctor visits for various check-ups when a child is born, to tweets, blogs, websites and social networking sites that a person might engage in. Overtime the digital dossier accumulates a lot of material so that it is possible when a person born in 2000 reaches 30yrs of age there is no longer a need to go visit the parents to look at baby pictures, rather all that information would be available and accessible through some form of network, because it has been archived since before the person was born.

An examination of one’s digital dossier is not mentioned or alluded to in the current definition of digital literacy or the discussions of new literacies. Consequently, students in schools are taught how to critically examine what others produce and to question the validity of different perspectives presented in digital forms (a case can be made that even this is not being done well), however what is missing is a lesson on self-examination.

In 2011, world governments and leaders were overthrown because of injustices that they committed against their own people, which are brought to light by the use of mobile devices. The power of mobile devices has extended the nature by which humans are connected, a critical examination of the role the individual plays not only in critically examining what they’ve read or seen, but rather what they’ve created and posted is a necessary aspect of a new digital literacy or a creation of a new literacy all together.

Another motivation for the evaluation of the current understanding of digital literacy is the nature by which mobile devices have allowed those traditionally viewed as disenfranchised and marginalized to enter the conversation.

The argument against the investment in ICTs especially in Afrikan schools has often revolved around whether such an investment is worthy of consideration more so than other pressing needs such as addressing, HIV/AIDS, malnutrition, malaria, etc. (Slay & Dalvit, 2008). This ‘can’t chew and work/walk at the same time’ or ‘the one thing at a time approach’ is no longer the only option. Mobile devices have taken away the absence of communities in the “developing world” from the global conversation while they address “more pressing issues”. Mobile devices and the effect they’ve had have also allowed for different communities to be looked at from their perspectives because of what they contribute to the overall network. This has moved the conversation from the generic global village to recognising that even as technology there are still differences amongst cultures. This realisation has prompted Mills (2010) therefore conclude that “while giving acknowledgment to the significant advances in digital communication technologies, there is not a single global village—rather, there are groups with varied levels of participation in digital practices across local villages around the world” (p. 262).

As argued by Millis (2010), in her survey of the literature, new literacies have often been concerned with the digital divide and leave the impression that technology is leaving those in marginalised and low income communities at a disadvantage. Although there are constraints, those in marginalised communities are finding a way to enter into the dialogue and are not simply shut out.

Put simply, the conversation should no longer be solely about how the marginalized are left out of the conversation but rather how they are altering the conversation because they are taking part. Whether the various gatekeepers and those in privilege positions are recognising it, the fact remains that those that did not participate before are not only part of the conversation, but they are beginning their own conversations that have nothing to do with what has been designated as the topic du jour. Like water they are seeping through at all different crevices albeit slowly.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have argued that the current framing of digital literacy does not go enough to include the changes and affordance that are brought on by mobile devices. We are proposing for an expanded definition of digital literacy which takes into account the different “practices across multiple technologies, media, modes, text formats, and social contexts” (Mills, 2010, p 262).

In agreement with Kress (2010), we believe that the new definition of digital literacies (even if it does not result in the name we propose of Mobile Digital Literacy – MDL), it must have the following three components:

- the rapid evolution of digital technologies;

- a new more pervasive emphasis on multimodality in digital communications;

- a new approach to communication and interaction that is best characterised by an emphasis on design rather than a highly separable distinction between ‘writing’ and ‘reading’ (p5).

The choice is to either make room at the table by broadening the definition of digital literacy or to create a new table introducing a new category that includes mobile devices. The traditional way of defining literacy & digital literacies is coming up short – we need to include the different things that mobile devices contribute, and as such we must continue to reconfigure what we traditionally know as literacy.

References

Ahmed, M. (2011). Defining and measuring literacy: Facing the reality. International Review of Education. Volume 57, Numbers 1-2, 179-195, DOI: 10.1007/s11159-011-9188-x

Alberts, D. S. and Papp, D. S. (1997). Information Age: An Anthology on Its Impact and Consequences, National Defense University, Washington, DC, USA.

Buckingham, D. (1993) Children talking television. The Falmer Press: London.

Burniske, R. (2000) Literacy in the cyberage: Composing ourselves online. Skylight: Illinois

Clancy, S., & Lowrie, T. (2002). Researching multimodal texts: Applying a dynamic model. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Australian Association for Research in Education, Brisbane, Australia

Clark, L., & Visser, M. (2011). Chapter 6: Digital Literacy Takes Center Stage. Library Technology Reports, 47(6), 38-42.

Cope, B. and Kalantzis, M. (Eds) (2000) Multiliteracies. Macmillan: South Yarra.

GSMA (2015). Accelerating digital literacy: Empowering women to use the mobile internet. Retrieved from https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/DigitalLiteracy_v6_WEB_Singles.pdf

GMCA. (2017, July). Accelerating Affordable Smartphone Ownership in Emerging Markets GMCA.com. Retrieved from https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/exec-summary-accelerating-affordable-smartphone-ownership-in-emerging-markets-2017.pdf

Kalantzis, M, Cope, B. and Fehring, H. (2002) Multiliteracies: Teaching and learning in the new communications environment. PEN 133, PETA: Marrickville.

Kirisci, P. T., Fennell, A., Klen, E., Gokmen, H., O’Connor, J., Thoben, K. D., … & Klein, P. (2012). Supporting inclusive design of mobile devices with a context model. INTECH Open Access Publisher.

Knobel, M., and Healy, A. (1998) Critical literacies in the primary classroom. PETA: Newtown, Australia.

Kress, G. (2010) The profound shift in digital literacies. In Gillen, J & Barton D., 2010. “Digital literacies: A research briefing by the technology enhanced learning phase of the teaching and learning research programme,” London: London Knowledge Lab, at http://www.tlrp.org/docs/DigitalLiteracies.pdf, accessed 18 November 2011.

Mills, K. A (2010). A Review of the “Digital Turn” in the New Literacy Studies. Review of Educational Research June 2010, Vol. 80, No. 2, pp. 246–271 DOI: 10.3102/0034654310364401

Mitra, S. (2012). The Hole in the Wall Project and the Power of Self-Organized Learning. Retrieved from https://www.edutopia.org/blog/self-organized-learning-sugata-mitra

Muspratt, S., Luke, A., and Freebody, P. (1997) (Eds) Constructing critical literacies. Allen and Unwin: St. Leonards, Australia.

Palfrey, J. & Gasser, U (2008). Born Digital: Understanding the First Generation of Digital Natives. New York: Basic Books.

Pietrass, M. (2007). Digital Literacy Research from an International and Comparative Point of View. Research in Comparative and International Education, Volume 2, Number 1, 2007

Semali, L. (2002) ‘Defining new literacies in curricular practice’. In Reading online: New literacies. http://www.readingonline.org/newliteracies/action/alvermann/index.html

Smyth, T. S. (2011). The New Literacy: Technology in the Classroom. Online Submission.

Sunga, T., Chang, K., & Liua, T. (2015). The effects of integrating mobile devices with teaching and learning on students’ learning performance: A meta-analysis and research synthesis. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360131515300804

Telecomlead (2019). India’s active mobile users reached 1,026.37 mn: TRAI. Retrieved from https://www.telecomlead.com/telecom-statistics/indias-active-mobile-users-reached-1026-37-mn-trai-89104

The New London Group, (2000) ‘A pedagogy of Multiliteracies designing social futures’, in Cope, B. and Kalantzis, M. (Eds) Multiliteracies. Macmillan: South Yarra.

Weinberger, A., Clark, D.B., Häkkinen, P. Tamura, Y., Fischer, F. (2007). Argumentative Knowledge Construction in Online Learning Environments in and across Different Cultures: a collaboration script perspective. Research in Comparative and International Education, Volume 2, Number 1, 2007

Wagner, D. A. (1991). Literacy as culture: Emic and etic perspectives. In E. M. Jennings & A. C. Purves (Eds.), Literate systems and individual lives: Perspectives in literacy and schooling (pp. 11-22). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

This resource is no cost at https://open.library.okstate.edu/learninginthedigitalage/