Chapter 3: Team Work and Collaborative Writing

Michael Beilfuss

Chapter Synopsis

This chapter covers some of the fundamentals of team work. After introducing the importance and prevalence of team work in the professional world and workplace, the chapter describes how best to build teams and ensure that they run smoothly. One of the first things a team needs to do is take an inventory of each member’s qualifications. Assessing qualifications allows teams to better assign roles, some of which are described in this chapter. Once the team has been built and everyone knows their roles, the planning stage begins – specific responsibilities are allocated among the group members to best fit their qualifications, the group writes out a schedule, and plans for any problems that may arise either within or outside the group. The chapter ends with a number of tips for a successful team project.

3.1 Introduction

Collaboration is a necessary task in most workplaces. Collaborative writing is one of the common ways people in the worlds of business, government, science, and technology handle large writing projects. In the professional and scholarly worlds, a lot of time, research, and energy have been devoted to understanding how teams work, and how to make them work more effectively. There is an entire industry devoted to assisting companies and organizations to get the most out of teamwork. In your career, you are more than likely to encounter situations where you have to work, and write, collaboratively. This chapter aims to help you develop the knowledge and skills to work effectively in groups.

Some people dislike group work due negative past experiences. They may be the person who seems to do more work than others, they may dislike having to rely on another person to follow through, or maybe they feel it was difficult to pull together so many ideas from so many people. Others do not mind it. They may have had positive experiences and see the value in group work. In fact, if done correctly, collaboration can be an effective tool to getting work done.

Thanks to ever emerging new technologies, writers can collaborate in exciting new ways. Using tools such as Google Docs, writers can work on texts synchronously even when they are separated by continents and oceans. Using discussion forums, musicians can exchange and remix chords with other artists from around the world. Via Skype, writers can talk with one another as they collaborate in a shared white space. And then there is Wikipedia, one of the most successful collaborative writing project ever conceived and executed. Clearly, good collaboration skills are more important now than ever before.

In our e-culture, being a successful collaborator is crucial to success. Today's workers use multiple media to share and construct meaning. Today's workers must be symbol analysts and are especially social in terms of how they communicate and learn.

When the first cave man started doodling on a stone canvas, he probably had colleagues looking over his shoulder, suggesting that he hold the brush a different way, mix the paint differently, perhaps make the buffalo appear fiercer, and so on. Many people find discussions with trusted colleagues to be an invaluable way to develop and polish ideas. Professionals in most disciplines, for example, attend conferences so that they can discuss ideas with colleagues and leading researchers. Writers in business and scientific contexts commonly work in teams with individuals responsible for their areas of expertise, such as marketing language, audience, finance, research, and editing. Some authors do not feel comfortable beginning a new project until they have discussed their ideas with others. Successful writers do not wait until they have completed a project before seeking constructive criticism. Instead, they share early drafts with critics.

This chapter will provide information and resources to help you master collaboration skills.

3.2 Building a Team

In the 1960s the psychologist Bruce Tuckman described four stages of team building: Forming, Storming, Norming, and Performing. While there has been a lot of research since then on team formation, Tuckman’s stages are still often considered the benchmark for team building. You can find any number of articles, books, and videos that elaborate on Tuckman’s research. For a quick overview, have a look at this Mind Tools article and brief video: “Forming, Storming, Norming, and Performing: Understanding the Stages of Team Formation” [1] before you read the rest of this chapter.

If you can choose your partners for a collaborative project, it is tempting to choose friends and/or people with similar backgrounds as yourself. If the project is deeply discipline-specific, this may be a good idea. Working with friends and close colleagues can help ease the awkward, early stages of a project. However, projects that require teams often include aspects from multiple fields and disciplines.

When you begin picking team members for a writing project in a technical writing course, you should consider choosing people with different backgrounds and interests. Just as a diverse, well-rounded background for an individual writer is an advantage, a group of diverse individuals makes for a well-rounded writing team. As a side note, it is never a good idea to work in a team with a romantic partner. It can be annoying and awkward for the rest of the team to watch as you and your partner canoodle or bicker. And modern romance such as it is, nothing can damage a team quicker than a romantic break-up in the middle of a project.

At the same time, collaborators can become obstacles, requiring constant supervision. In group situations, other students can fail to attend classes or out-of-class meetings; they can ignore your efforts and just focus on their own missions or visions about ways documents should be written. When collaborators do not do their job, they can become an annoyance--just another obstacle rather than a support and an inspiration to colleagues.

The whole truly can be larger than the sum of its parts. Through collaboration, we can produce documents that we alone could not imagine. Collaborators can inspire us, keep us on task, and help us overcome blind spots.

Due to the many potential problems with teamwork, it is crucial at the beginning of any team project to do the following:

- Articulate and clarify team members’ qualifications

- Define roles for each member

- Establish responsibilities of each team member

Qualifications

As a first step, you want to identify any strengths and weaknesses. There are at least two ways to think about qualifications: 1. knowledge, skills, and abilities, and 2. personality types.

The first aspect—knowledge, skills, and abilities—is pretty straightforward. The engineer in your group should work on the engineering aspect, the accountant should work on the financials, the lawyer should work on the legal matters, and you want the marketer to work on PR. When writing proposals for external clients (and sometimes even internal proposals) you may be asked to include résumés of each of the team members. This is to help demonstrate the group’s strengths through its expertise and diversity.

The second aspect of qualifications is perhaps a little fuzzier and has to do with interpersonal relations. A recent study by Google found that “psychological safety” – that “team members feel safe to take risks and be vulnerable in front of others” – is the most important characteristic of effective teams.[2] One can only feel safe in a group if they are comfortable with the other team members’ personalities.

Articulating personality skill sets can help divide the work most effectively, and help avoid unnecessary conflict and confrontation. For example, if someone in the group is very social and outgoing, they might be the best person to stop people on campus to ask them survey questions. If someone in the group is a careful listener, they should probably be one of the people who talks to clients or experts. If one of the team members is more studious, or internet savvy, perhaps they should complete more secondary research. The Meyers-Briggs test activity at the end of this chapter may be a good method to begin to understand personality types and how to best harness their strengths.

Roles

Once the group has completed an honest assessment of its strengths and weaknesses, you can move on to determine the roles for each member. Roles are slightly different from responsibilities. Roles describe each individual’s general purpose and duty on a team. It designates their main areas of concern. On the other hand, responsibilities refer to the specific tasks each member will complete.

To use a sports analogy – the position you play on a team is your role, but the specific responsibilities during a game will often shift, sometime from play-to-play or even within a play. In football, a wide receiver’s responsibilities vary greatly – on one play it is to get open for a reception, on another it may be to cross up the defense to allow another receiver to get open. A wide receiver could be called on to block a defensive player, or in rare circumstance even pass the football. Sometimes a wide receiver must instantly switch their responsibility from offense to defense, and tackle an opponent who just intercepted a pass. But the role of a wide receiver is never likely to be confused with the roles of a center who snaps the ball, or a linebacker who is always looking to tackle the person with the ball.

Every project is slightly different and demands different roles but some common roles include:

- Leader/Coordinator/Project Manager: this person is not the boss, but rather the person who makes sure that everything runs smoothly. They do not give orders or make demands, but rather they serve to keep the group operating at its best and sticking to schedules.

- Monitor: this member keeps track of decisions and their outcomes and keeps an eye out for any potential flaws or conflicts.

- Recorder/Note Taker/Secretary: this person is responsible for keeping the records of the group. They should be able to tell everyone what was agreed and when. They keep the notes (or minutes) of the meetings.

- Shaper: this team member often has the big ideas, the drive to see them through, and the assertiveness to steer the group.

- Investigator/Researcher: whether it is through secondary or primary research, this person likes to look for answers to the questions driving the project. In a big project, everyone will likely contribute some research, but this person would be the one who dives into the topics the most.

- Specialist: often referred to as subject-matter experts (SMEs), this is the person with the deep background on a topic. Often groups will have specialists in more than one area.

- Editor: the best writer will often write the least amount of original content in a large project – rather their role will be to edit and improve upon everyone else’s writing. They also help create one voice in documents written by multiple people with multiple writing styles.

- Designer: the designer is the person who makes sure any documents, presentations, videos, or websites created by the team look appealing and professional. As the name implies, they are in charge of graphics and design.

For more on some of these common roles, and others, see “The Nine Belbin team Roles.” [3]. Just like a wide receiver, you might find you have to take on a variety of responsibilities related to your role as well as some responsibilities that seem tangential to your role. You might also find you have to take over unfamiliar responsibilities because someone else “dropped the ball.” Defining roles helps establish accountability in the group and makes it clear who is in charge of what.

Responsibilities and Planning

Once you have articulated the qualifications of each member and established the roles, it is time to assign responsibilities and plan the project. This includes dividing the work, creating a schedule, and anticipating problems (obstacles and conflicts). You should also agree on the main avenue of communication, and create an online document and/or folder that will be shared by all group members.

Capture your team's roles, responsibilities, and decisions in a simple team-plan document. It can contain the key dates in the team schedule, a tentative outline of the document to be team-produced, formatting agreements, individual writer assignments, word-choice preferences, and so on. The planning stages will often include all or most of the following actions:

- Analyze the writing assignment

- Pick a topic

- Define the rhetorical situation

- Brainstorm and narrow the topic

- Create an outline

- Plan the research (primary and secondary)

- Plan a system for taking notes from sources

- Plan any graphics you would like to see in your writing project

- Agree on style and format questions

- Develop a work schedule for the project and divide the responsibilities

- Develop a system for resolving disputes

Much of the work in a team-writing project must be done by individual team members on their own. When dividing the work, aim for these minimum guidelines:

- Have each team member responsible for the writing an equal amount of the assignment.

- Have each team member responsible for locating, reading, and taking notes on an equal amount of sources.

Some of the work for the project that could be done as a team you may want to do first independently. For example, brainstorming, narrowing, and especially outlining should be completed by each team member on their own; then get together and compare notes. Keep in mind how group dynamics can unknowingly suppress certain ideas and how less assertive team members might be reluctant to contribute their valuable ideas in the group context. If you noticing this happening, be proactive and ask for everyone’s thoughts or opinions – especially those group members who may be hesitant to talk over others – so that good ideas do not remain unheard.

After you divide the work for the project, write a formal chart or calendar and distribute it to all the members.

Scheduling

Early in your writing project, set up a schedule of key dates and deadlines. This schedule will enable you and your team members to make steady, organized progress and complete the project on time. It is a good idea to figure a day and time during the week when all group members are free and can meet, in person or online. Block off that hour every week. Before you meet, write out an agenda that includes all the main topics of discussion, including old business, ongoing business, and new business. The agenda should include a time schedule for the meeting to make sure everything is covered in the time allotted for the meeting. If you find one week that there is no real reason to meet, you can cancel it.

As shown in the example schedule below (Figure 1), your project schedule should include not only completion dates for key phases of the project but also meeting dates and the subject and purpose of those meetings. Notice these details about that schedule:

- Several meetings are scheduled in which members discuss the information they are finding or are not finding. One team member may have information another member is looking everywhere for.

- Several meetings are scheduled to review the project details, specifically, the topic, audience, purpose, situation, and outline. As you learn more about the topic and become more settled in the project, your team may want to change some of these details or make them more specific.

- Several rough drafts are scheduled. Team members peer-review each other's drafts of individual sections at least twice, the second time to see if the recommended changes have worked. Once the complete draft is put together, it too is reviewed twice.

| Individual prototypes due | October 1 |

|---|---|

| Team meeting: finalize the prototype | October 1 |

| Rough-draft style guide due | October 5 |

| Team meeting: finalize style guide | October 5 |

| Twice-weekly team meetings: progress & problems | October 5 - 26 |

| Graphics sketches due to Jim | October 14 |

| Rough drafts of individual sections due | October 26 |

| Review of rough drafts due | October 28 |

| Team meeting: discuss rough drafts, reviews | October 28 |

| Update of style guide due from Sterlin | October 31 |

| Revisions of rough drafts due to reviewers | November 3 |

| Final graphics due from Jim | November 5 |

| Completed drafts to Sterlin: final edit/proof | November 7 |

| Team meeting: review completed draft with final graphics and editing | November 12 |

| Completed drafts due to Julie for final production | November 15 |

| Team meeting: inspection of completed project | November 15 |

| Project upload due to McMurrey | November 16 |

| Party at Julie's | November 19 |

Figure 1: A project schedule in the form of a simple table.

Anticipating Problems and Conflicts

Think about how to resolve typical problems that can arise in a team project and document your team's agreements about these matters in a by-laws document:

- Workload imbalance. When you work as a team, there is always the chance that one of the team members, for whatever reason, may have more or less than a fair share of the workload. Therefore, it is important to find a way to keep track of what each team member is doing. Periodic group evaluations and self-assessments, including logging hours spent on the project, can help accomplish a good balance of work.

Both during and at the end of the project, if there are any problems, the evaluations and assessments should make that fact clear and enable a more equitable balancing of the workload. Before the end of the project, team members can add up their hours spent on the project; if anyone has spent a little more than their share of time working, the other members can make up for it. Similarly, as you get down toward the end of the project, if it is clear from the evaluations and assessments that one team member's work responsibilities turned out, through no fault of their own, to be smaller than those of the others, they can make up for it by doing more of the finish-up work such as typing, proofing, or copying.

- Team members without relevant skills. Sometimes a member may claim to have no relevant skills. That could just be an indication of that person's anxiety or lack of interest in engaging in a group project. Each team member in a writing course should contribute a fair share of the writing for a project. However, there are plenty of tasks that do not require technical knowledge, formatting skills, or a sharp editorial eye, for example: typing and distributing the team plan, the by-laws, and the minutes of team meetings; or reminding team members of due dates and scheduled meetings. In fact, except for the anxiety or lack of interest, the self-professed unskilled team member might make the best team leader!

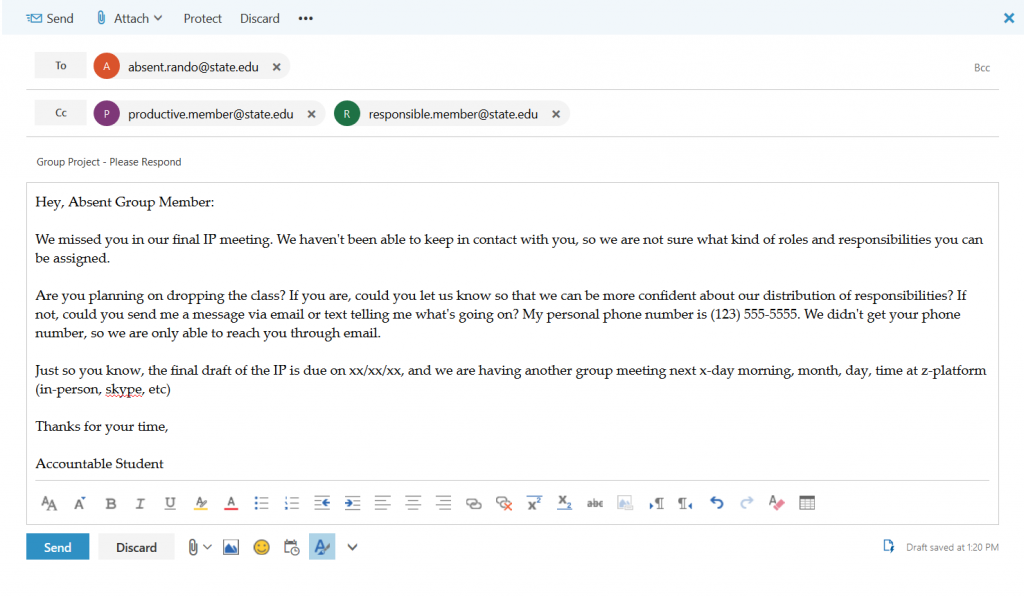

- Disappearing team members. If your team is unfortunate enough to have an irresponsible member who simply vanishes, have a plan for what to do about that, and document it in your team by-laws. One obvious solution is to kick the team member off the team and inform the instructor (if it is a writing course) or the next level of management (if it is a nonacademic organization). Of course, you want to try to avoid losing a team member, so constant communication is a key ingredient to well-functioning groups. The sample email below (Figure 2) demonstrates that the team leader did all they could to get the disappearing member back in the fold, and is about to give them up as lost.

- Seemingly entrenched team-member disagreements. It is amazing how vehemently team members can disagree on aspects of a team-writing project. Have a plan, written in your team by-laws, how to resolve these matters. Should they be put to a vote? Flip a coin? Should you "escalate" the matter to a neutral or higher-level party? Do you have a group mediator who can be impartial and make judgement calls?

- Radically inconsistent writing styles and format. Because the individual sections will be written by different writers who are apt to have different writing styles, set up a style guide in which your team members list their agreements on how things are to be handled in the paper as a whole. These agreements can range from the high level, such as whether to have a background section, all the way down to picky details such as when to use italics or bold and whether the phrase you group wants to use is "click" or "click on."

Before you and your team members write the first rough drafts, you cannot expect to anticipate every possible difference in style and format. Therefore, plan to update this style sheet when you review the rough drafts of the individual sections and, especially, when review the complete draft.

One of the best ways to smooth out the different writing styles is to have everyone consistently work on the entire document together. That is, read all the sections and make comments and edits throughout the writing process. Then, at the very end, have one person edit the entire document for consistency and design.

Communication

Good communication is the key to successful team projects. You should decide early on how you will communicate (group text, email, an app, etc) and how you will share documents.

Once the team is formed and work begins, it is imperative that any issues that arise are addressed early. Most group conflicts start as miscommunication and/or misunderstanding. Everyone in the group should always be a part of any information that is sent between members. Include all members in all communication, even if it does not seem all that important. That is what the cc line is for in emails.

Team projects are generally evaluated on their own merits, regardless of group dynamics and participation. In other words, you cannot tell a client that one of your team members was slacking and that is why the graphics and design does not look so nice. In a professional setting, who did how much work does not matter to the client – they only care about what the team delivers.

Although some members in the group may fulfill different roles and do more or less writing, in a project for a writing class, each member of a group should contribute actual writing and research to the project.

Group work needs to be a collaborative effort. If someone in the group is not pulling their weight, it needs to be addressed right away. Sometimes it is due to simple misunderstanding. Discuss problems with the entire group as soon as possible, but if that does not work, contact your instructor (or supervisor in a professional setting) so you can sort things out before it is too late. There are usually a number of opportunities to evaluate and assess the group as the project unfolds. However, it is not possible to quit the group or kick someone out without serious repercussions. In the workplace, there is no leaving a group project unless you quit you job.

3.3 Completing the Project

Try to schedule as many reviews of your team's written work as possible. Communicate and meet regularly and read each other’s work as often as possible. You can meet to discuss each other's rough drafts of individual sections as well as rough drafts of the complete paper.

A critical stage in team-writing a paper comes when you put together those individual sections written by different team members into one complete draft. It is then that you will probably see how different in tone, treatment, and style each section is. You must, as a group, find a way to revise and edit the complete rough draft that will make it read consistently so that it will not be so obviously written by three or four different people.

When you complete reviewing and revising, it is time for the finish-up work to get the draft ready to hand in. That work is the same as it would be if you were writing the paper on your own, only in this case the workloads can be divided among the group.

3.4 Final Thoughts

Business leaders commonly complain that college graduates do not know how to work productively in groups. In American classrooms, we tend to prize individual accomplishment, yet in professional careers we need to work well with others. Unfortunately, the terms "group work," "team work," or "committee work" can appear to be oxymorons – like the terms "honest politician" or "criminal justice." Many groups, teams, and committees simply do not work, despite the potential of individuals in the group.

It is certainly true that many people waste time in group situations, politicking as opposed to defining tasks and solving problems. In writing classrooms, some students want to slide by, get the grade without doing the work; others are willing to do the work, but are not sure how to proceed. While working in groups presents unique challenges, your success as a writer, leader, or manager is somewhat dependent on your ability to help others focus, communicate, and collaborate.

Tips for Effective Groups

Follow these tips for nurturing teamwork in group situations. Try experimenting with the following strategies to help ensure the success of group work.

- When the group first meets, select a project manager. This person provides leadership and helps forge consensus and a coherent plan. Being a leader is different from being an autocrat or a dictator. Even if you are selected as the project manager, it is important to remember that you are an equal team member and collaborator who has simply been assigned the task of coordinating the project and ensuring that progress does not fall behind schedule. This does not, in effect, make you the “boss” of all the other team members, so remember to act like a partner rather than an overlord. As team coordinator, your attitude and behavior may help set the tone for the rest of the group.

If you are the leader, be sure to make fair assignments and let others own ideas and parts of the project. If people slack off, talk to them discreetly, giving them fair warning before speaking with other members or your teacher. Be concrete and specific about building consensus regarding shared goals, due dates, and processes.

- All team members need to work to be positive. Be generous. Be respectful regarding members' feelings and needs. Focus on the strengths of the members in your group. Give more than you take. Ideally, collaborative projects should not be about one person being in control. Decisions should be made by the group, not by one individual.

- Respect different ideas and approaches. Listen before talking; be articulate about your position but flexible when others want to go another way.

- Clarify evaluation criteria up front. Understand what your instructor wants, how the documents will be evaluated, and what the due dates are.

- Beyond outlining the project, come up with a project management plan, outlining:

- Responsibilities for each group member

- Descriptions of the steps or tasks involved in implementation

- Timelines for completion

- Summaries of problems/opportunities you anticipate (and a list of possible solutions/recommendations)

- Draft a document planner for the group project. Write a research proposal and submit it to your instructor/supervisor. Your proposal—which is formal request that will be discussed at length in the Proposal chapter—should identify what you want to do, how you want to do it, and when you can have it done.

- Your instructor (or supervisor) may request that you maintain individual journals or progress reports or keep a log of your contributions to the project. Alternatively, you can log about your collaborative efforts in a wiki, perhaps writingwiki.org. The advantage of using the wiki space is that it enables group members to enter their contributions on the same page. Teachers appreciate the wiki format because each edit to a page is recorded by the wiki software, enabling the instructor to see when particular contributions were made and by whom. Teachers can account for individual efforts when you keep records and perhaps include a one-page summary about what you learned as a result of the collaborative experience. Create a Web portfolio for the project with an index or default page that links to major sections of the group project and relevant appendixes. Report appendixes should include links to the document planner, the document proposal, individual students' journals, and related resources.

- Evaluate your peers' contributions; be sure to copy your peers on your evaluation.

Group work can be difficult, and the amount of time required to complete a group project may very well take longer than if you were tackling the project on your own, but group work can also be a richly rewarding experience with synergistic results that are impossible to achieve otherwise. With a clear understanding of each group member’s strengths and qualifications, with clearly articulated roles and responsibilities, and with a well-defined plan, any group project can be a success.

3.5 Activity

You might consider having everyone in the group take the Meyers--Briggs personality test (http://www.humanmetrics.com/cgi-win/jtypes2.asp) to get a good sense of where everyone is coming from and where they stand. There are a number of free versions of the test online. The official version from the Meyers and Briggs Foundation [4] is far more thorough and costs money.

The test measures preferences and general attitudes and can help you understand communication and learning styles. In conjunction with the other skills, knowledge, and abilities, it can help determine which roles and tasks are most suitable for each team member.

After taking the test, record your personality type and some of it is major attributes. Then meet with your group so you can all share your results and discuss how best to capitalize on the knowledge.

[1] https://rework.withgoogle.com/guides/understanding-team-effectiveness/steps/identify-dynamics-of-effective-teams/. This is a great resource to learn more about effective group dynamics.

Attribution

Material in this chapter was adapted from the works listed below. The material was edited for tone, content, and localization.

Strategies for Peer Reviewing and Team Writing, by David McMurrey, licensed CC-BY.

Working in a Team, Writing Commons, by Joe Moxley, licensed CC-BY-NC-SA.

ENGL 145 Technical and Report Writing, by the Bay College Online Learning Department, licensed CC-BY.

- https://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/newLDR_86.htm ↵

- https:///rework.withgoogle.com/guides/understanding-team-effectiveness/steps/identify-dynamics-of-effective-teams/. This is a great resource to learn more about effective group dynamics. ↵

- https://www.belbin.com/about/belbin-team-roles/ ↵

- https://www.myersbriggs.org/home.htm?bhcp=1 ↵