Chapter 10: Research

Staci Bettes

Chapter Synopsis

In this chapter, you will learn how to plan for conducting different types of research, depending on your research goals. The chapter starts by giving information on creating a hypothesis and research questions to guide your research. After, you will learn about conducting both primary and secondary research and when to choose one or the other. Different kinds of primary and secondary research are discussed, to help you decide which is best for your specific project and needs. Information for creating your own survey and interview questions is included, as well as tips for evaluating secondary sources.

10.1 Introduction

With the abundance of research available today, often the hardest part of research is deciding on the best type of research for a specific project, and evaluating its validity and effectiveness. What does it mean to be information literate? Simply stated, information literacy is the ability to locate, evaluate, and implement information efficiently.

In college, you typically find, evaluate, and use information to satisfy the requirements of an assignment. Assignments often specify what kind of information you need and what tools you should use or avoid in your research. For example, your professor may specify that you need three peer-reviewed academic articles and that you should not cite Wikipedia in your final paper. However, in life beyond college—especially the work world—you may not have that kind of specific guidance. You may also be asked to create your own data using techniques such as interviews, surveys, and analysis, instead of using published sources. Using research in the portions of your document that require evidence can strengthen your argument and help answer your research questions. At other times, even if research is not actually necessary, it can be persuasive and sharpen the points you want to make.

Research is much more than doing a simple search engine query and reviewing the first ten results it returns—you need to be information literate in order to plan and perform your own research efficiently, effectively, and with the needs of your audience in mind. You must also be able to incorporate unbiased, reliable data for your projects.

10.2 Hypothesis and Research Questions

In the technical field, you may be asked to complete research for several reasons. Research can be used to confirm theories (hypotheses), gather information over a topic and necessary services, describe a population, find a solution to a problem, and/or to provide background information. You will likely perform research for most, if not all, the documents you create in class or the workplace. For example, you may do background research on a group of people to revise a document for that audience, such as to tailor your résumé for a position at a specific business. Or, you may research a problem in order to provide a solution and present that research in a report. Depending on the genre, you may need a specific type of research, or a combination of several types. The type(s) of research you choose should be based on your purpose, audience, and, often when completing a research project, your hypothesis and research questions.

Hypothesis

It can be difficult to decide where to start researching for your task, especially if you are not given specific guidelines. Most scientific or medical research begins with a hypothesis. A hypothesis is tentative, testable answer to a question. It is based on your current knowledge of the situation or topic; therefore, it is a “guess” of what the outcomes will be. For example, a pharmaceutical company creates a new prescription strength sunscreen for people with an elevated risk of melanoma. They theorize that daily use of the sunscreen, applied every three hours with normal sun exposure, will lower the risk of skin cancer by 75%. This is a classic example of a hypothesis. You may or may not be asked to create a hypothesis for a research topic. It depends on the purpose and topic, or the type(s) of research you need to produce.

When you create a hypothesis for your problem or topic, it is always written as a statement. It is predictive in nature and typically used when some knowledge already exists on the topic. In the sunscreen example above, scientists in the pharmaceutical industry should have knowledge on how the product and individual compounds work before it goes to clinical trials. Based on your hypothesis, you can collect data, analyze it, use it to support or negate the hypothesis, and (eventually) arrive at a conclusion at the end of the research.

Hypotheses work to limit the scope of your research. A complete hypothesis should include the variable, the population, and the predicted relationship between the variables. For example, some limits on the sunscreen example are the number of applications per day and a “normal” amount of exposure (as opposed to working outside all day without protective clothing). A hypothesis also applies to a specific population—in this case, people with elevated melanoma risk. Once established, a hypothesis will guide your research for credible outcomes.

Research Questions

Whether or not you create a hypothesis, you will often create research questions to help direct your research. These questions need to be answered through your research for you to thoroughly investigate and analyze a topic. What are the major questions that need to be answered for you to create a solid conclusion about your topic? For example, imagine you are asked to research the effect of final exams on student academic success. There are many areas you could choose to focus on—student mental or physical health, knowledge attainment and/or recall, effectiveness of timed exams, cumulative exams versus application of materials, and so on. As there are so many aspects of this topic, you will most likely not have time to adequately research all of them. Establishing research questions will help you focus your research on specific areas of the topic.

How do you decide which areas are the right areas to research? Base your decision on factors such as:

- What is your area(s) of interest?

- What will be most likely to persuade the reader? (Did they ask for a specific type or area of research? What is their main goal for the research? What do they want to alter, improve, or disprove? Which of the audience’s needs, wants, or values might help guide your research?)

- What areas can you feasibly research within the time frame or any other limitations you have?

- Are there any areas where research seems to be missing or underdeveloped on the topic?

Once you decide on a few areas of focus, you can construct research questions to help guide you. Normally, three or more questions are standard for a topic. They should be written in the form of a question and must be inquisitive in nature. A properly written question will be clear and concise, and contain the topic being studied (purpose), the variable(s), and the population. If you were doing research on the final exam example above for a university’s Student Affairs office, your research questions might be:

- What is the current system for final exams, and what are the reason(s) for its structure and schedule?

- How does the current system compare to other similar universities, including scheduling, exam grades, GPA, and overall graduation rates?

- Have any connections been proven between the final exam system and student academic success or failure?

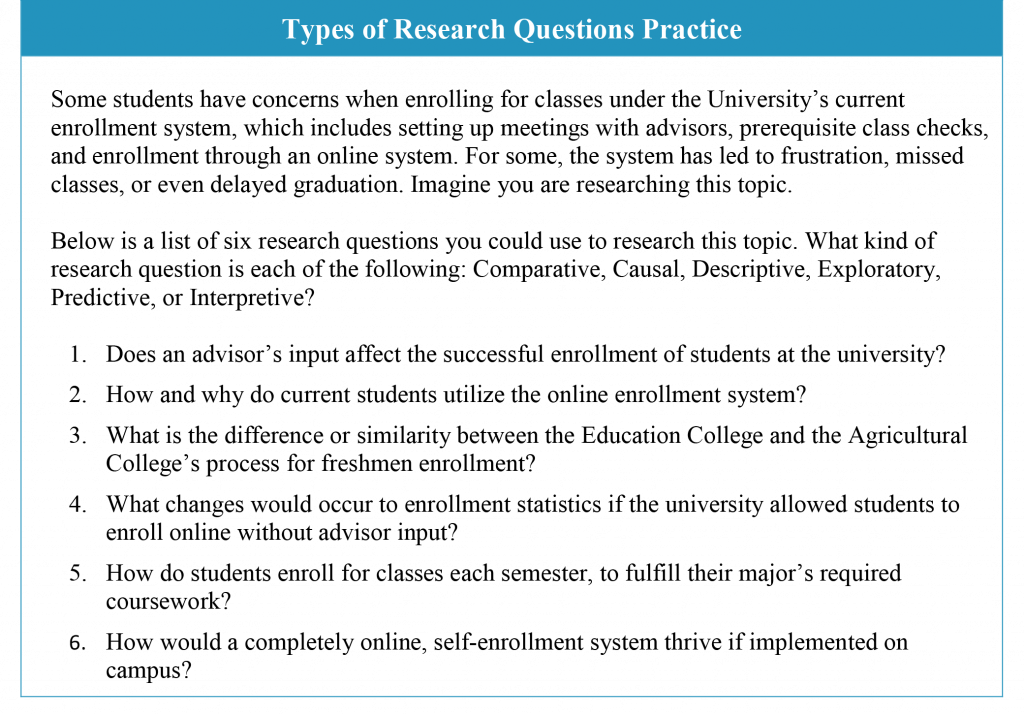

The type of question you choose depends on the best way you can study your topic and your hypothesis. The following list includes the six main types of research questions:

- Comparative questions: look for the similarities and differences between multiple variables.

- Causal questions: look for relationships between two or more occurrences.

- Descriptive questions: seek out a description and explanation for a specific situation.

- Exploratory questions: help try to better understand something through observation.

- Predictive questions: determine what will happen in the future or if a change happens.

- Interpretive questions: gather feedback on a topic or perception without altering the outcome.

After creating your questions, you will need to decide the best type(s) of research to help you answer them.

Figure 1: Types of Research Questions Activity

10.3 Choosing Research Types

There are numerous types of research and source types available to complete your research. The type of research you choose should be based on the rhetorical situation of the document, as well as the assumptions you make about the main audience. For example, for a basic argumentative essay, you generally use secondary research from published, peer-reviewed sources. However, with technical documents, the type of research will often vary. For instance, if you are creating a proposal on a community issue, you may incorporate local news sources stories about the topic and community demographics, in addition to creating a community survey.

No source type is better or worse than others. What matters is that it addresses the following areas for your specific topic, genre, and audience. Does it:

- Help you learn more background information?

- Answer your research question?

- Convince your audience that your answer is correct?

- Describe the situation surrounding your research question?

- Report what others have said about your research question(s)?

Source types are generally divided into two main categories—primary research and secondary research. Primary Research is research that you collect and create yourself. This can include activities such as observing your environment, conducting surveys or interviews, directly recording measurements in a lab or in the field, or even receiving electronic data recorded by computers/machines. Secondary Research is research that uses data and ideas that have been collected and analyzed by other individuals and published for others’ use.

Data Triangulation

For your research to be considered valid, it is often recommended that you triangulate your data. By triangulate, we mean that you include information from three different kinds of sources. For example, if you were researching the possible environmental effects of a new chemical plant built near a local river, you may choose to interview environmental biologists about the potential risks of the plant’s location, research national incidences of plant constructions near large bodies of water, and compare official water quality analytics from before and after the chemical plant appeared. Using three types of data is standard in academic publishing and scientific research; varied types of information work together to create a complex, larger argument. This also makes you, the author, appear more credible and your research more thorough.

As you begin your research process, keep a few ideas in mind.

1. Choose your research type based on what will yield data for your research question(s).

2. Ensure you have enough time to feasibly deliver your research in the time you have to complete a project.

3. Choose research and data that is ethical. (See chapter 4 for more information on ethics and research)

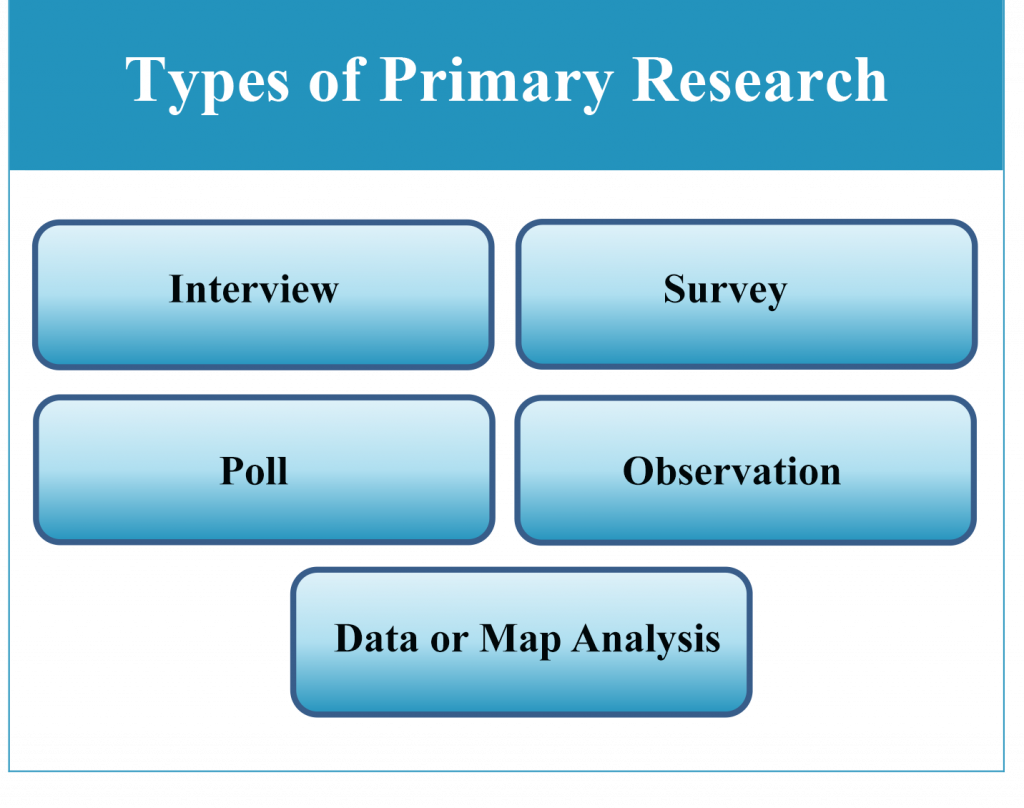

10.4 Types of Primary Research

Sometimes, the information you need is not yet written or published. For example, if you are creating a report over the feasibility of implementing a food pantry on your college campus, you will not likely find published data on how many enrolled students would actively contribute to the pantry. In these situations, you need to create your own data to back up your argument or answer your research question. These sources—where you create your own data—are known as primary sources. Below are details on several common types of primary research: interviews, surveys, polls, observations, and data or map analysis.

Interviews are one-on-one conversations between the interviewer and a person who has unique insight into the topic. Most of us use people as sources in our private lives, such when we ask a friend for a restaurant recommendation or whether a movie is worth watching. While we may ask people for their input daily, interviews are a formal way of gathering insider information on a topic we may otherwise lack. There are several factors you must consider when doing an interview for research purposes.

When choosing an interviewee, think about what type of information you need. Who can give you this insight? Who has the details? Can one person answer, or do you need multiple interviews? “Experts” are not just researchers with PhDs doing academic work. People can speak with authority for different reasons. They can have subject expertise (having done scholarship in the field), societal position (a relevant work title), or special experience (living or working in a particular situation). An up-close, firsthand view of the situation gives them the authority to speak as an expert on the topic.

There are several types of interviews to choose from. Choose the type based on the topic, the type of person(s) you wish to interview, and what is convenient for the interviewee. Some interview types include:

- Individual face-to-face: The standard interview, used for non-shy participants willing to share their thoughts on the topic.

- Telephone: A good option when travel is not possible, but it can be difficult to fully document the conversation.

- Email: A good option when schedules are conflicting; it allows for interviewee to respond at their convenience.

- Focus Group: Useful when a solo participant is hesitant or when you want to ask the same question(s) to multiple people.

In an interview, you want to ask questions to get insider details, unique observations, and experiences with the topic or current situation. Encourage the telling of stories and anecdotes. The best way to get insider information and detailed answers to is ask open-ended questions, or questions that ask for extensive details as opposed to single-word answers. (See section 10.5 for tips on writing open-ended questions) These details can add depth and insight to your topic, and sometimes even direct you to other areas you had not thought to research. Do not be surprised if an interview takes you off in completely new directions, one that turns out to be much more interesting than the direction you were following before.

Of course, interview content must be evaluated just like any other. Like any other source material, the answers and data you gather could be biased. Keep that possible bias in mind when using the information. That is part of exercising the critical thinking that research assignments are famous for producing. Potentially biased or not, sometimes a source’s firsthand experience is best, and recognizing what they offer can help you open up to diverse ideas and worldviews that you would otherwise miss. Use good interview techniques, such as putting the interviewee at ease, using active listening techniques to encourage them to talk, asking follow up questions, and thanking them at the end of the interview.

Survey

Paper or electronic surveys provide answers to questions related to the topic. But be aware that answers are often limited by the survey author, meaning the data gathered is only as good as the questions asked. Surveys are used to learn more about a specific group of people (also known as a sample), and include localized information such as attitudes, habits, or need for change.

You must first decide what type of information you need to know. What is the purpose of the survey? Who and what do you want to know more about? Surveys will target a certain group of people with specific characteristics. For example, if you wish to research the effectiveness of a new policy in the workplace, you would want to get responses from all departments that are affected by the policy—not just from one department. This group of people is called a sample. Your sample may have broad or limited characteristics, but it is important to target those who have the characteristics you desire.

The main categories of surveys are hardcopy (paper) and electronic. Your choice will depend on the topic and the sample—where and how are the best places to target your intended sample of people? In the above example, if you focus on employees of the business, you may get more responses by handing out paper surveys in the break room or by going desk-to-desk if you have a fairly mobile or collaborative workplace. However, if the workplace is more reserved or work is individual, an emailed electronic survey may be more effective. More often, people choose electronic surveys for convenience and distribute them via listservs, company email lists, and social media. On the job, your company may provide access to paid software, but there are many free options available, such as Google Forms, SurveyMonkey, and SurveyGizmo.

Unlike an interview, with surveys you want to mainly ask closed questions—questions where you offer a limited amount of responses to choose from. You can use some open questions, but most often you will provide the answer options (e.g., “Do you consider the following statement true or false?” or “How many times a week do you work out: a) 1-2 times; b) 3-4 times; c) 5-6 times; d) 7 or more times?”; e) Never).

For a successful survey, you will usually need two types of questions: demographic questions and content questions. Demographic questions ask for general characteristics of the respondent, such as age, location, or gender. The type of demographic questions you ask will depend on the sample for the survey. Content questions are questions about the topic you are researching. (See section 10.5 for tips on writing closed-ended questions) These give insight into the respondent’s feelings and knowledge of the topic you are researching.

Poll

Similar to a survey, a poll is a single, closed question asked of the target sample. The goal of a poll question is to gauge user’s feelings toward an idea, usually in one simple question—who is interested? Who has heard of this topic? Would the audience be interested in implementing a certain change? For example, perhaps you wish to know how many people in your workplace would prefer four day per week work schedule, you could easily create a poll question to get this information. You will not receive in-depth information with a single poll question; therefore, poll questions should be used in conjunction with other forms of research when used for professional research.

Observation

Observation is watching and describing an issue first hand, to create colorful descriptions and detail. Observation is a good choice when you want to learn more about the situation as it naturally occurs. Observe the issue when it is happening, based on prior knowledge. You will want to observe the issue more than once (preferably vary dates and times) to see if any patterns develop, if the magnitude of the problem differs from your original assessment, or if the problem is connected to other areas you may have not considered.

Observation should focus on recording details and creating detailed descriptions of the event. First-person observation is best, though you can get some insight from recorded images. The drawback of prerecorded images is that you only get information from one perspective, and may miss out on other observable sensory input; therefore, it is better to observe and make notes first hand.

The data needs to be verifiable—not just general impressions. Focus on specific incidents and conversations, describe the setting, and provide other concrete details that can be verified or observed via instrumentation. Record and describe your impressions in the moment; do not rely solely on memories. For example, a common issue across the university campus is crowding in the Student Union during lunch. Observing and recording details during lunch would allow you to describe the issue, identify different aspects of the problem, and later provide solutions based on your observations. However, you must make observations in a reliable way. If you wanted to determine whether there was sufficient seating in the Student Union during the lunch hour, it would not be enough to simply describe the dining area as “busy” or “crowded” around lunchtime. Instead, scientifically determine how busy and crowded the dining area is, perhaps by counting how many seats opened up within a given time period, or by count how many people ate their meal standing or sitting on the floor.

Data or Map Analysis

If your group has a topic that involves paperwork, data sheets, maps, or other document types, you may incorporate their analysi into your primary research. If you are doing research on specific issues in a building or business (number of available outlets, renovation or expansion plans, lack of office space for new employees, etc.), you could analyze blueprints, maps, or data spreadsheets. Imagine you are researching outlet availability in the campus library. You could consult maps of the library to see the current outlet locations and wiring accessibility. You could compare these maps to older versions of the library setup, or compare to maps of similar libraries to see how they provide enough outlets for students. If possible, use at least three similar documents for analysis to show a trend.

10.5 Creating Interview and Survey Questions

To prepare for several types of primary research (mainly interviews, polls, and surveys) you will need to create questions. The content of the questions should align with your research goals. These questions can be divided into two types—open-ended questions and closed-ended questions.

Before you begin drafting your surveys, interviews, or polls, you should learn as much about the topic—and your sample—as possible. Conducting secondary research on the topic and sample can help you get a solid foundation for your primary research. This will help you construct questions that glean solid data and help you tailor the research to the respondent(s). Then, construct your interview, survey, and poll questions to help “fill in the gap” created by missing or incomplete research on the topic.

Writing Open-Ended Questions

Open-ended questions are structured to encourage detailed responses which focus on the respondent’s experiences or feelings. The point is to encourage a lengthier answer; these questions should be asked in a way that requires more than a “yes/no” response. Open-ended questions are especially important for interviews. For example, you may ask someone, “What do you think about the candidates running for mayor?” This is an open-ended question that encourages a detailed response. To create open-ended questions, it is helpful to begin the question with words and phrases such as explain, describe, tell me about, or walk me through your experience with….

Writing Closed-Ended Question

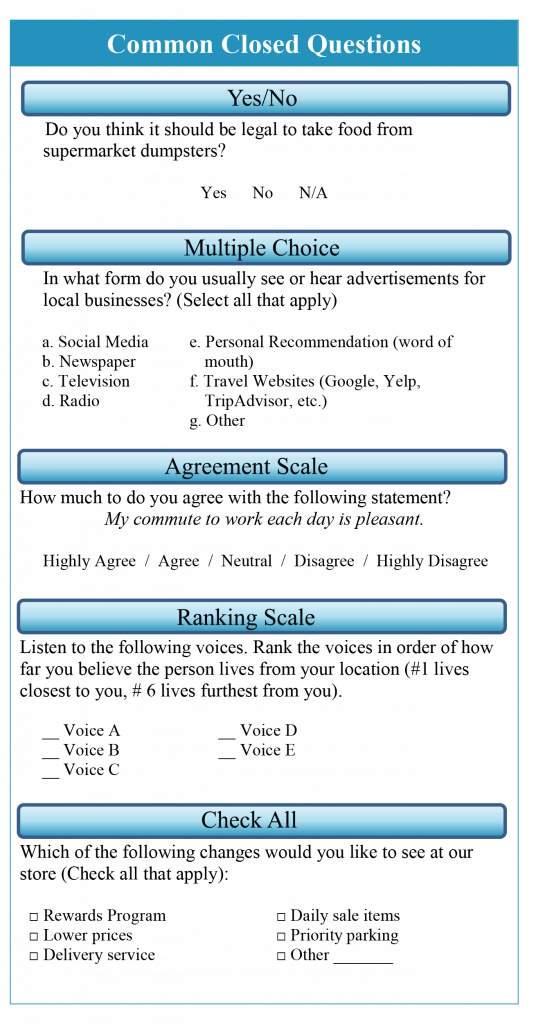

Closed-ended questions are structured to limit the available responses, usually to a single word, number, or phrase option. In the case of survey and poll questions, you can limit the response even further by providing answer choices. A closed-question version of the mayor example above is, “Which candidate for mayor do you like the most?” with the candidates’ names listed as answer options. Or “Do you believe the current campus dining options provide enough variety for vegetarian diners?”

Question Types

When you create closed questions for a survey or poll, you will also make decisions about the type of questions you use. There are several types of common questions types to choose from, including but not limited to: Ranking Scales, Agreement Scales, Yes/No Questions, Multiple Choice, and Check All That Apply.

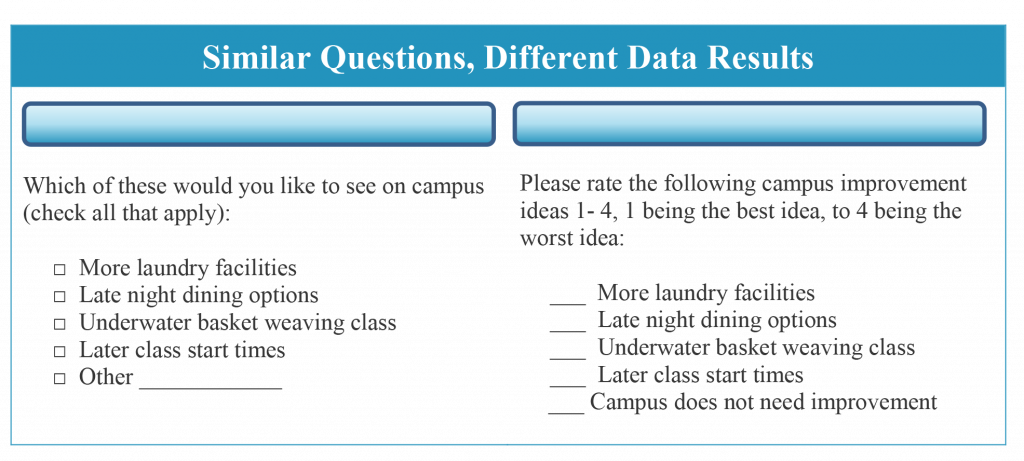

The type of question you choose will depend on the type of information you want to know. Below are two similar questions and answer options; however, the type of data gathered will be different. Imagine you are researching different types of campus improvements. If you ask students to “Check all that apply,” you can see which ideas are generally popular or unpopular. If you ask the students to “Rank” the ideas, you can use the data to infer which is the most popular, second most popular, and so forth. It is a slight distinction, but can make a difference during data analysis.

Creating Answers

You must give appropriate response choices for all closed questions. The type of responses will vary according to what type of info you need to know, how you can get as much variation/good data as possible, and also the type of question you ask. You should include at least one null answer option for most questions. For example, no answer, prefer not to answer, or other. This option allows respondents to answer questions when their option is not provided and/or continue the survey if a question makes them uncomfortable.

Common Issues

Regardless of whether you create an open or closed question, you should avoid negatively worded questions, double-barreled questions, and biased questions.

- Negatively worded questions: ask for negative data. For example, if you asked, “How many times per week are you unable to access the door lock after hours?” you are asking for how many times something does not occur. This type of phrasing can confuse some respondents, which could lead to bad data. It is best to revise these questions to ask for a positive amount, such as “How many times per week are you able to access the door lock after hours?”

- Double-barreled questions: ask about two or more ideas, such as, “How many times per week do you speak with staff and administration when you have a problem?” This question asks about two different ideas—speaking with staff and speaking with administration. The amount of contact per week could vary greatly between these two groups. In cases such as these, revise the question to address only one topic or split into multiple questions.

- Biased questions: make assumptions about the respondent or lead the reader to an answer. For example, “How many times a week do you encounter the terrible seating situation at the Student Union?” will encourage your audience to view the seating situation as “terrible” even if they had not previously considered the situation to be problematic. It can be difficult to not implant ideas, confuse the participant, or compile misleading information. For example, imagine you work for an ice cream company, and need to prove that chocolate ice cream is the most popular flavor. You ask in your survey, “Do you like chocolate ice cream?” Respondents will probably say “yes.” However, this is not a complete survey. Just because a person likes chocolate ice cream does not mean it is the most popular flavor. Instead, you should ask several questions, one of which might specifically ask respondents to reveal their favorite ice cream flavor.

At other times, you may lead the respondent with phrasing or make assumptions of how the respondent answered earlier questions. For example, if you are doing research over extending library hours, you could ask:

- Do you think the library should extend their hours?

Yes / No / Maybe / NA

- When should they extend they extend their hours?

4-6am / 12-2am / Open 24 hrs

- What technology do you want to improve at the library?

printers / more computers / more outlets

In the above example, the second question is written as though the answer to the first question will be Yes, but that may not be the case. What if the person answered No or Maybe to the first question? The second question has no option to allow for dissent or disagreement. Also, question three assumes that the respondents want to improve something technology-related (without them saying so), and the responses limit the answers to only three areas of technological improvement.

Once you have decided on the type of information you need from your surveys or interviews, make sure you go back and revise your question structure and phrasing to avoid bad data through negatively-worded questions, double-barreled questions, and biased phrasing.

10.6 Performing Secondary Research

When conducting primary research, you gather and create new data. With secondary research, you utilize established, published data created by another author(s). While it may seem a bit “simpler” to use secondary research, there are many aspects to consider when choosing and incorporating these sources. You must make choices about the source’s validity, biases, author and publication credibility, and information quality.

In today’s complex information landscape, just about anything that contains information can be considered a potential secondary source. For example, most know about books, websites, journals, and newspapers. However, other possible sources include research reports, conference papers, field notes, photographs, websites, and television programs. With so many sources available, the question usually is not whether sources exist for your project, but which ones will best meet your information needs? Categorizing a source helps you understand the kind of information it contains, which is a clue to whether it might meet your information needs and where to look for it and similar sources.

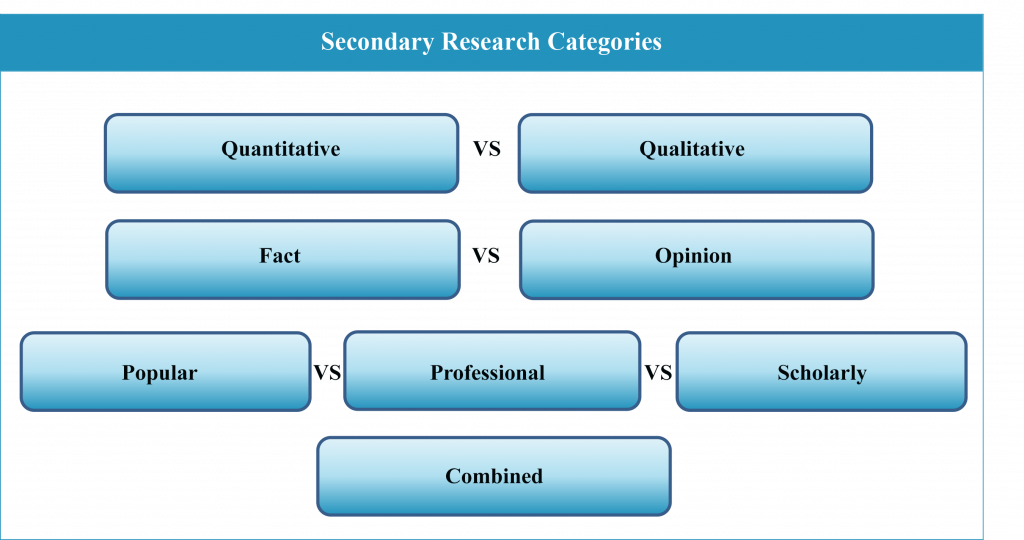

A source can be categorized by whether it contains quantitative (numerical) or qualitative (descriptive) information or both; whether the source is objective (factual) or persuasive (opinion); whether the source is a scholarly, professional, or popular publication; and the source’s format. As you may already be able to tell, sources can be in more than one category at the same time because the categories are not mutually exclusive.

Quantitative or Qualitative

Information from a secondary source can be quantitative or qualitative, which is a key way to categorize sources. Some sources contain either quantitative information or qualitative information, but sources often contain both. Quantitative information involves a measurable quantity—numbers are used. Some examples are length, mass, temperature, and time. Quantitative information is often called data, but can be things other than numbers. Qualitative information involves a descriptive judgment using concept words instead of numbers, such as descriptions of a situation and interview data. For example, if you were researching how to improve your local library, quantitative information could include government documents with statistics on current usage and advertisements for library activities at similar libraries. Qualitative information could be published case studies on library use or a local newspaper story with interviews of library patrons.

Fact or Opinion

An author’s purpose can influence the kind of information they choose to include in a source. Think about why the author produced a source, because that reason dictated the kind of information they include. Depending on that purpose, the author may have chosen to include factual, analytical, and objective information. Or, it may have suited their purpose to include subjective, and therefore less factual and analytical, information. The author’s reason for producing the source also determines whether they included multiple perspectives or just their own. For example, a blogger may review a movie based on personal opinion (e.g., they liked the action scenes or thought the main actor was dreamy), while, a professional movie critic would approach their review differently (e.g., scene composition, musical score, and other quantifiable elements).

Popular, Professional, and/or Scholarly

We can also categorize information by the expertise level of its intended audience. Considering how “expert” one has to be to understand the information can indicate whether the source has sufficient credibility and thoroughness. There are varying degrees of expertise:

- Popular: Popular newspaper and magazine articles (The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal and Rolling Stone) are meant for a large general audience, are generally affordable, and are easy to purchase or free. They are written by staff writers or reporters, and are often about news, opinions, background information, and entertainment. They are visually attractive with catchy titles, artwork, and advertisements, but no footnotes or references. They are published by commercial publishers and content is approved by an editor.

- Professional: Professional magazine articles (Plastic Surgical Nursing and Music Teacher) are meant for people in a particular profession. Staff writers or other professionals write at a level and with language understood by those in the profession. They are about trends and news from the targeted field, book reviews, and case studies. Articles are often less than 10 pages and may contain footnotes and references. These are usually published by professional associations and commercial publishers, and like popular publications, are published after approval from an editor.

- Scholarly: Scholarly journal articles (Plant Science and Education and Child Psychology) are meant for scholars, students, and the general public who want a deeper understanding of a topic. Researchers and scholars write these articles to present new knowledge and further understanding of their field. They contain findings of research projects, data and analytics, and case studies. They are often long (over 10 pages) and include footnotes and references, and are usually published by universities, professional associations, and commercial publishers. Content is approved by peer review or the journal’s editor.

Combined Purposes

Sometimes authors have combined purposes, as when a marketer decides he can sell more smart phones with an informative sales video that also entertaining. Authors often have multiple purposes in most scholarly writing. For example, scholarly authors want to inform and educate their audiences, but they also want to persuade the reader that what they report and/or postulate is a true description of a situation, event, or phenomenon, or a valid argument that their audience must take a particular action. In this blend of purposes, the intent to educate and inform is considered to trump the intent to persuade.

Intent Matters

Author intent matters in how useful their information can be to your research, depending on which information need you are trying to meet. For instance, when you look for sources that will help you answer a research question or evidence for your answer, you will want the author’s main purpose to be to inform or educate. With that intent, they are likely to use facts where possible, multiple perspectives, little subjective information, and seemingly unbiased, objective language that cites where they got the information. This kind of source will lend credibility to your argument.

Common Secondary Research Types

- Books: usually a substantial amount of information, published at one time and requiring great effort on the part of the author and a publisher

- Magazines/Journals: published frequently, containing articles related to some general or specific professional research interest; edited

- Newspapers: daily or weekly publication of events of social, political and lifestyle interest

- Websites: digital items, each consisting of multiple pages produced by someone with technical skills (Or have the ability to pay someone with technical skills.)

- Articles: distinct, short, written pieces that might contain photos and are generally timely (Timeliness is when something is of interest to readers at the point of publication or something the writer is thinking about or researching at a given point of time.)

- Conference papers: written form of papers delivered at a professional or research-related conference (Authors are generally practicing professionals or scholars in the field.)

- Blogs: frequently updated websites that do not necessarily require extensive technical skills and can be published by virtually anyone for no cost to themselves other than the time they devote to content creation (Usually marked by postings that indicate the date they were written.)

- Documentaries: visual works such as a film or television program, presenting political, social, or historical subject matter in a factual and informative manner (Often consists of actual news films or interviews accompanied by narration.)

- Online videos: short videos produced by anybody, with a lot of money or a little money, about anything for the world to see (Common sites for these are YouTube and Vimeo.)

- Podcasts: digital audio files, produced by anyone and about anything, and are available for downloading (Often by subscription.)

10.7 Evaluating Secondary Sources

Evaluating sources for relevance and credibility is important to establish the validity of the data and ideas within. There is never a 100% perfect source. You will need to make educated guesses about whether the information is good enough for your purpose. Critical thinking is a necessary skill your professors and employers will expect. Learning to evaluate sources can also keep you from being duped by fake news and taken advantage of by posts that are ignorant or simply scams.

To help evaluate the quality of a source, ask yourself the following questions about each source:

- Authority:

Question: Is the person, organization, or institution responsible for the intellectual content of the information knowledgeable in that subject?

Indicators: Formal academic degrees; years of professional experience; active and substantial involvement in a particular area; awards and recognition.

- Accuracy:

Question: How free from error is this piece of information?

Indicators: Correct and verifiable citations; information is verifiable in other sources from different authors/organizations; author is authority on subject; information has been properly edited to display professional care.

- Objectivity:

Question: How objective (unbiased) is this piece of information?

Indicators: Multiple points of view are acknowledged and discussed logically and clearly; statements are supported with documentation from a variety of reliable sources; purpose is clearly stated; the organization’s “About” statement reveals a commitment to truth; the organization’s readership cannot be easily divided along common demographic lines (e.g., gender, political affiliation, age, etc).

- Currency:

Key Question: When was the item of information published or produced?

Indicators: Publication date; assignment restrictions (e.g., you can only use articles from the last five years); your topic and how quickly information changes in your field (e.g., technology or health topics will require more recent information to reflect rapidly changing areas of expertise).

- Audience:

Question: Who is this information written for or this product developed for?

Indicators: Language; style; tone; bibliographies.

10.8 Citing Sources

If you create your own research data using primary research (interview, survey, etc.), you do not need to provide a formal citation for that data—because you created it, you own it. However, you must properly cite any information you use from all secondary sources.

Direct Quote

Researchers document anything that is directly quoted. This can be a phrase, sentence, paragraph, or longer section taken from a source. Make sure to place quotation marks ( “ ” ) around the borrowed material to show that it is exact phrasing used in the source. You must also provide a correct citation at the end of the sentence containing the borrowed information and create a full reference at the end of the document on a reference page.

Paraphrase and Summary

Paraphrased or summarized information also needs to be documented using a citation. Paraphrasing is restating ideas taken from someone else and putting those ideas into your own words. The language used needs to be original and fresh. You cannot simply switch a sentence around or use a thesaurus to swap out a few words. You must completely put the source’s ideas into the writer’s own word (this is usually done by turning away from the source material and rephrasing the author’s statements from memory). Quotation marks are not used, but you must use a citation to give credit to the original source. It is also helpful to add attributive tags to the paraphrase.

If you have difficulty deciding if you should choose a direct quote, a paraphrase, or a summary in your document, think about the following rules:

- Use a direct quotation: if the wording is very eloquent or clear, or if changing the wording would make the quote lose its impression. You can also directly quote an authority on a topic to add credibility.

- Use a paraphrase: if the idea is more important than the wording. Also use a paraphrase to change the emphasis of an idea, change the style of wording, show your understanding of complex ideas, condense lengthy ideas into more concise explanations, or link together ideas that might otherwise be separated by lengthy paragraphs or pages of supporting documentation.

- Use a summary: when you need to simplify or condense a larger work into the basic points.

Visuals

Any visuals, graphics, and pictures which you did not create yourself need to be cited. Often, individuals think they can snag an image from Google and copy and paste it into a paper or presentation without citing it; this is plagiarism. Anything that was not created in whole by the writer needs to be cited. You may also wish to limit image search results to open source images only before selecting a graphic to use, to avoid copyright issues. (See chapter 4 for instructions to limit your online graphics search)

Overall

Always give credit to another person’s ideas or work; never pass them off as your own. There are numerous format styles available, such as MLA, APA, CSE, and AMA. If you are not given a specific format to use in your document, choose a style used in your field and ensure you are using it correctly. Guides are available online for every style, as well as detailed published manuals for when you need to get more in-depth. A few websites that may help you with citations include: Reference©ite Quick©ite (https://www.cite.auckland.ac.nz/2.html), The Owl (https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/purdue_owl.html) , Citation Machine (www.citationmachine.net), and Cite This for Me (http://www.citethisforme.com/).

And of course, your university library has many format and style guides, both electronic and print format, to help you with basic citations and more specific, stylized aspects of format. (See chapter 4 for information on ethics and citation).

Attribution

Material in this chapter was adapted from the works listed below. The material was edited for tone, content, and localization.

Choosing & Using Sources: A Guide to Academic Research, by Cheryl Lowery, licensed CC-BY.

Technical Writing, by Allison Gross, Annamarie Hamlin, Billy Merck, Chris Rubio, Jodi Naas, Megan Savage and Michele DiSilva, licensed CC-BY-NC-SA.

ENGL 145 Technical and Report Writing, by the Bay College Online Learning Department, licensed CC-BY.