Chapter 3: Life-Span and Life Course Theories of Aging

Learning Objectives

After reading through Chapter 3: Psychological and Sociological Theories of Aging, students should know, learn, or be able to do the following:

- Analyze Psychological Perspectives on Aging: Compare and contrast the psychological theories of aging presented in Chapter 3 with those rooted in biology and genetics from Chapter 2, evaluating their underlying principles and implications.

- Explore Gerotranscendence Theory Dimensions: Appraise the dimensions comprising the Theory of Gerotranscendence, critically evaluating their significance and potential impact on the aging and developmental process.

- Evaluate Life-Span Developmental Approaches: Assess Paul Baltes’s holistic developmental approach to aging, considering how multiple perspectives are integrated and how this approach contributes to a comprehensive understanding of aging and human life span development.

- Apply Selection, Optimization, and Compensation Theory: Utilize the components of the Selection, Optimization, and Compensation (SOC) Theory to analyze and propose strategies for managing challenges associated with aging.

- Synthesize Classical Sociological and Psychological Aging Theories: Construct a comparative analysis outlining the distinctions between sociological theories of aging and psychological/biological theories, highlighting key differences and their implications for understanding aging processes.

- Synthesize Life Course Theory Principles: Synthesize the five principles of the Life Course Theory, and demonstrate their interconnectedness in shaping individuals’ life trajectories and experiences across various stages of life.

Chapter Outline

Psychological Theories of Aging

Erikson's Eight Stages of Psychosocial Development

Erik Erikson (1950) proposed one of the better known psychologically based theories of aging and lifespan development. This classic theory provides a useful guideline for thinking about the changes humans experience beyond childhood and into the second half of life. Erikson proposed that human aging and development functioned on the basis of the epigenetic principle. This principle suggests that humans developmental largely through a pre-determined and genetically influenced unfolding of personalities across eight stages. Our progress through each stage is partially determined by our success or lack of success in addressing certain developmental tasks at each stage. Each stage entails developmental tasks that are psychosocial in nature; thus entailing an interaction between our ego identity and the social environment. Erikson (1950) proposed that each developmental period of life presents a unique challenge or crisis that persons confront, referred to as psychosocial crises. According to Erikson, successful development involves dealing with and resolving the goals and demands of each of these psychosocial crises in a positive way. Erikson referred to the management of such crises as involving dystonic, or negative dispositions (i.e., isolation, stagnation, despair) versus syntonic or positive dispositions (i.e. intimacy, generativity, integrity). These crises are usually called stages, although Erikson consider each development period to involve resolution of opposable dispositions. Nonetheless, if a person does not fully resolve a stage in a positive manner, it may hinder their ability to deal with the impending challenges one will face at later stages in life. For example, if a person does not develop a sense of trust (Erikson’s first stage) early in life, they may find it more difficult as an adult to form positive intimate relationships during the emerging adult years (Erikson’s sixth stage); or an individual who does not develop a clear sense of purpose and identity (Erikson’s fifth stage) may become self-absorbed rather than work toward meeting the concerns and betterment of others (Erikson’s seventh stage). However, most individuals are able to successfully complete the eight stages of Erikson’s theory without much difficulty.

| Age Range | Psychosocial crisis | Positive resolution of crisis |

|---|---|---|

| Birth to 12 to 18 months | Trust vs. Mistrust | The child develops a feeling of trust in caregivers |

| 18 months to 3 years | Autonomy vs. Shame/Doubt | The child learns what can and cannot be controlled and develops a sense of free will. |

| 3 to 6 years | Initiative vs. Guilt | The child learns to become independent by exploring, manipulating, and taking action. |

| 6 to 12 years | Industry vs. Inferiority | The child learns to do things well or correctly according to standards set by others, particularly in school. |

| 12 to 18 years | Identity vs. Role Confusion | The adolescent develops a well-defined and positive sense of self in relationship to others. |

| 19 to 40 years | Intimacy vs. Isolation | The person develops the ability to give and receive love and to make long-term commitments. |

| 40 to 65 years | Generativity vs. Stagnation | The person develops an interest in guiding the development of the next generation, often by becoming a parent. |

| 65 to death | Ego Integrity vs. Despair | The person develops acceptance of how one has lived |

Erikson further posited that the successful resolution of psychosocial crises across various the developmental life periods contributes to the acquisition of positive character.

| Developmental Period | Psychosocial Virtue |

| Infancy | Hope |

| Toddlerhood | Will |

| Young Childhood | Purpose |

| Childhood | Competency |

| Adolescence | Fidelity |

| Emerging Adulthood | Love |

| Middle Adulthood | Care |

| Later Adulthood | Wisdom |

For example, when a young adult achieves a sense of social intimacy over feelings of social isolation, they gain an understanding of love. Mid-life adults who positively develop a general concern toward building a lasting legacy and guiding the next generation through concern and commitment above and beyond feeling frustrated with the demands of life and unhappy in achieving a work-life balance. Meanwhile, Erikson maintained that older adults who reflect upon and accept the totality of their life experiences and achievements, whether good or bad, come to achieve a sense of life satisfaction rather than a feeling of disappointment and despair. Moreover, the acceptance of one’s live experiences fosters an improved understanding surrounding the many meanings and lessons learned in life, or which Erikson referred to as the acquisition of wisdom.

Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory of Development has received various criticism over the years. Erikson’s theory has been criticized for focusing too heavily on the concept of “crises;” thus assuming that the completion and resolution of one crisis is a prerequisite before the next or other future crisis in psychosocial development can be addressed. Erikson’s theory has also been criticized as focusing too much on the social expectations that might commonly be found in certain cultures, but not in all. For instance, the idea that adolescence is a time of searching for identity might translate well in the middle-class culture of the United States, but not as well in cultures where the transition into adulthood coincides with puberty through rites of passage and where adult roles offer fewer choices.

Joan Erikson’s Ninth Stage Concept

Joan Erikson, the wife of Erik Erikson, extended an edited version of Erikson’s original eight stages of psychosocial development in a written work entitled, The Life Cycle Completed (Erikson, 1997). In this work, Joan Erikson conceptualized the Ninth Stage. The Ninth Stage Concept referred to the psychosocial development of long-lived adults, notably persons living 90 years and longer. Joan Erikson acknowledged that outliving familiar social supports and surviving into very old age presents unique developmental changes in physical mental, social functioning. Old-old adults commonly have a greater need for

- Behavioral health monitoring in meeting everyday activities of living (i.e., shopping, cooking, eating; toileting);

- Assistive devices (e.g., hearing, visual, and mobility aids);

- Modifications to the built environment (i.e., ramps, grab bars, accessible doorways) and;

- Long-term care assistance.

Joan Erikson proposed that such needs contribute to an increased interdependence upon family and community relationship for success in development. However, many long-lived adults outlive their familiar familial and social network supports from which they depend for meeting everyday tasks of living. To complicate matters, most old-old adults have been culturally socialized since birth to value, seek, and preserve individual autonomy, rather than to burden family or request the assistance of community supports, such as in-home care services, meals-on-wheels programs, or transportation services. In some cases, long-lived adults may begin to ask: Why am I still here? Joan Erikson proposed that, persons reaching the Ninth Stage experience a developmental shift in which they begin to psychosocially “age-in-reverse” through the varying developmental crises or tasks of psychosocial development. Joan Erikson theorized that learning how to trust rather than mistrust others represented a key development entry point into the Ninth Stage of life. Joan Erikson believed that old-old adults who gained a sense of trust and reliance upon others entered into the Ninth Stage with improved ability to meet a higher-order developmental task: finding faith in humanity. At the core of this task was the acquisition of humility, or the virtue of “being human.” Joan Erikson coined the ninth stage developmental process as gerotranscendence or acts of contemplation and resolution surrounding one’s human experience or condition that goes beyond self, others, and time to the point that continued survival and even death are no longer feared, but accepted as purposeful to humanity.

| Ninth Stage Process | Ninth Stage Developmental Tasks |

|---|---|

| First Stage | Accepting one’s life situation |

| Second Stage | Feeling others are concerned and care about one’s situation |

| Third Stage | Seeking intimacy and accepting love from others |

| Fourth Stages | Feeling respected by others for “who I am.” |

| Fifth Stage | Achieving new standards of how to “be” rather than to do |

| Sixth Stage | Feeling included by others to make choice and decisions |

| Seventh Stage | Accepting what can and cannot be controlled |

| Eight Stage | Becoming interdependent and trusting of others |

| Ninth Stage | Faith and understanding in humanity |

Theory of Gerotranscendence

Lars Tornstam (2005) revised and expanded the concept of gerontranscendence into a developmental theory of positive aging. Tornstam (2005) postulated that gerotranscendence consists of three primary dimensions which become markedly observable among long-lived adults. Tornstam (2005) posited the following dimensions as reflecting the construct of gerotranscendence:

- Cosmic Dimension

- Childhood reminiscence – process of life reconciliation through increased storytelling and narrative reconstruction and oral sharing of life events and memories, many of which occurred during childhood;

- Connection to earlier generations – increased flashbulb memories and recall of former or deceased family members to whom one has had a life-long emotional connection, as well as an expressed desire with whom one wants to be near once in the present and after death;

- Life versus death – transformation and disappearance of rumination, worry, anxiety, and fear of death in favor of accepting and appreciating the wholeness of one’s life;

- Mysticism – increased interest, contemplation, and acceptance of “unexplained,” “coincidental,” “consequential,” or mysterious experiences and events surrounding one’s life;

- Joyfulness – expression of gratitude and contentment for the “little” things that matter most in life including that which may be observed in nature, involving the cycle of life, or subtle human experiences.

- Selfing Dimension

- Self-confrontation – discovery, recognition, and understanding of the good and bad of oneself and personhood, as well as how one may or may not have presented the self to others;

- Diminished self-centeredness – removal of self as the center of one’s own universe and development shift toward positive self-esteem and confidence that feels appropriate and with equal regard and respect for others;

- Body transcendence – continuation of care for one’s physical body without obsessing over or drawing attention over one’s state of health functioning;

- Self-transcendence – shift from perceptions and expressions of egoism to a increased sense of altruism, empathy, and self-less care and concern for others with whom one may or may not know or be socially connected;

- Ego-integrity – increased desire for acceptance, tranquility, and contentment involving the formation and piecing together of fragmented and momentary life experiences into the “wholeness” of one’s past, present and future.

- Social and Personal Relationship Dimension

- Valued Social Relations – diminished preference to associate with superficial relationships in favor of selectively associating with social ties that provide maximum social and emotional benefit as well as bring increased value and meaning to one’s life and opportunities for solitude;

- Role Playing – renew understanding of one’s social commitments accompanied by an urgency to abandon past roles in favor of understanding one’s current role and place in both time and space;

- Emancipated innocence – abandonment of needless social conventions, technologies, and ways of doing things in favor of expressing innocence to enhance the maturity of self and others;

- Modern ascetism – Increased understanding and appreciation of wealth versus freedom and happiness via living within one’s means by maintaining enough for the basic necessities of life without the necessity of needing, wanting or competing for more;

- Wisdom – Increased demonstration and expression of open-mindedness, behavioral tolerance and the withholding of judgements or advice to others when approached by others with ethical dilemmas involving right versus wrong

Althought the Theory of Gerotranscendence provides a contemporary approach to understanding human development among long-lived persons, critics have suggested that the theory is too focused on micro-level process (i.e., individual lived experiences, subjective viewpoints) and fails to explain how macro-level factors (i.e., demographic or family and community context) impact how persons in very old age transcend and find meaning in life (Rajani, 2015). Furthermore, critics have noted that the theory also fails to account for the cognitive and mental health of very old adults, noting that it is difficult to judge to what extent to which common geriatric mental disorders such as dementia, depression, and anxiety impact positive ego development among long-lived adults. Finally, some critics have remarked that Torstam assumes gerotranscendence is developmentally universal, yet the theory does not take into account culturally dependent factors that contribute to divergent positive aging outcomes within and across Western versus non-Western cultures.

Life-span Human Development Theory

Paul Baltes (1987) devised a more holistic theoretical approach to aging and human development that moved beyond basic ages and stages. Baltes (1987) favored a continuous and contextual approach to thinking about aging and human development. Of central interest was providing theoretical understanding and explanation regrading the gains and losses persons experience across the span of biopsychosocial development beginning from the moment of concept until death. A secondary Several foundational principles provided the framework of a lifespan perspective (Baltes, 1987;Baltes, Lindenberger, & Staudinger, 2006):

- Development is lifelong. Lifespan theorists believe that development is life-long, and change is apparent across the lifespan. No single age period is more crucial, characterizes, or dominates human development.

- Development is multidirectional. Humans change in many directions. We may show gains in some areas of development, while showing losses in other areas. Every change, whether it is finishing high school, getting married, becoming a parent or grandparent, or becoming a caregiver to a parent entails both growth and loss. Today we are more aware of the variations in development. We no longer assume that those who develop in predictable ways are normal and those who do not are abnormal. So the assumption that early childhood experiences dictate our future is also being called into question. Instead, we have come to appreciate that growth and change continue throughout life and experience continues to have an impact on who we are and how we relate to others. Moreover, we recognize that adulthood is also a dynamic period of life marked by continued cognitive, social, and psychological development.

- Development is multidimensional. We change across three general domains/dimensions; physical, cognitive, and psychosocial. The physical domain includes changes in height and

weight, sensory capabilities, the nervous system, as well as the propensity for disease and illness. The cognitive domain encompasses the changes in intelligence, wisdom, perception, problem-solving, memory, and language. The psychosocial domain focuses on changes in emotion, self-perception and interpersonal relationships with families, peers, and friends. All three domains influence each other. It is also important to note that a change in one domain may cascade and prompt changes in the other domains. For instance, an adult who has begun planning for retirement will encounter many financial choices and work-related decisions, thus fostering developmental change in adult understanding linked to the timing and transitioning form work-related roles into new social or family roles. - Development is multidisciplinary. Human development is such a vast topic of study that it requires the incorporation of theories, research methods, and perspective of many academic disciplines. Reliance on multiple disciplinary perspectives rather than just one solitary viewpoint of aging provides a more holistic and well-rounded understanding of what contributes to adaptation to age-associated change and the acceptable levels of performance that will allow the aging individual to maintain success over loss or failure with advancing age.

- Development is characterized by plasticity. Plasticity is all about our ability to change and that many of our characteristics are malleable, or capable of being altered or influenced by socio-environmental or other contextual influences. For instance, plasticity is illustrated in the brain’s ability to learn from experience and how it can recover from injury or impaired functioning.

- Development is multicontextual. Development occurs in many contexts. Baltes (1987)

identified three specific contextual influences:- Normative age-graded: An age-grade is a specific age group, such as a emerging adult, middle-aged adult, or older adult. Humans in a specific age-grade share many expected and similar experiences and developmental changes.

- Normative history-graded: A history-grade refers to the time period in which individuals are born. In particular, a cohort is a group so persons who are born during the same year or roughly within the same time period in a specific society. This group of persons age through life often experiencing and witnessing similar historical circumstances and experiences.

- Non-normative life influences: Despite sharing age and history with our peers, each of us will age through life and encounter unique experiences that seemingly shape our own individual development. For instance, child who loses a parent at a young age has experienced a life event not typical of others within her age group. This event will likely shape development uniquely and differently for this individual as they continue to grow old.

Selection, Optimization, and Compensation (SOC Theory)

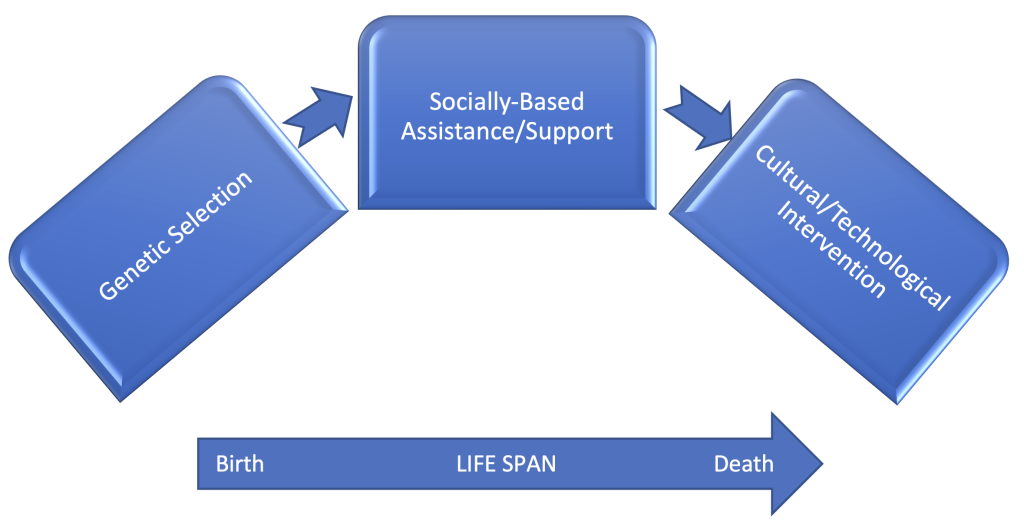

Baltes (1997) referred to the architecture of human development as an incomplete process involving ontogenesis, or the entirety of development biologically, psychologically, and socially from the time of conception to the moment of death. Baltes (1997) was particularly intrigued by developmental processes in the fourth age, or persons living 80 years and older. Baltes (1997) considered this period of life to be the most evidence form of developmental incompleteness and essential to understanding the interplay between gains and losses across the human life-span. Baltes (1997) posited three key dynamics that govern human aging and development across the life-span (see Figure 3.1).

First, evolutionary selection benefits decrease with age. In other words, the transmission of genetics vital to the unfolding and timing of human physiological performance, cognitive functioning, and goal directed social behaviors begins to operate inefficiently. Human become less genetically protected and gradually unable to recover fully from negative genetic attributions in the form of disease and disablement, in the second half of life. Genetic attributes become activated during this time and come to be manifested in the form of chronic and even lethal ailments one must manage and maintain to prevent further losses in functioning.

Second, human development and aging increases our need for culture. As humans experience more frequently encounter marked set-backs or declines in the form of physical or cognitive functioning, impairment, or disease; they develop a greater need for social support and cultural assistance to mitigate the selective evolutionary pressures of genetics warranting decline and loss. In other words, humans require culture-based resources in the form of education, medical technologies, economic assistance, community support services, and caregiving. Such socio-cultural resources allow those older in age to compensate or adapt to losses in biological and psychological potentials in order to generate or maintain appropriate levels of functioning necessary to live safely and independently. However, the effectiveness of such resources are not enough to ward off human aging.

This reflects a third and final dynamic in which the efficacy of culture decreases with age. The human organism is unable to fully recover from the experience of set-backs and losses which impact high-level performance in biological and cognitive potentials. With age, humans are unable to reach the same levels of functioning as they once enjoyed when younger or even with extensive cultural interventions (e.g., exercise, diet, brain fitness). The cultural resources of which one depends in old age are essentially rendered ineffectively in ceasing the end to life. The losses encumbered by the human organism essentially outnumber any gain that can be made or any ability to maintain acceptable levels of functioning necessary to sustain life. Therefore, the life of the human organism is cut-short from reaching full developmental success by the fact of an ontogenetic directional course.

To better represent developmental dynamics across the human life-span, Baltes (1987) formulated Selection, Optimization, and Compensation (SOC) Theory. Baltes (1997) framed that individuals always maintain a specific set of targets or goals involving their functioning, or what is termed selection. As we age, Baltes (1997) noted that development generally proceeds within the conditions of evolving constraints in time and resources surrounding limited capacity in functioning. Humans possess behavioral dispositions or characteristics which they are able to effectively activate or perform despite encountering loss. Such processes allow the individual to maintain plasticity and to adapt to loss. Thus, the individual will selectively target such dispositions in the form of a refined set of new goals which they aim to pursue and achieve. For instance, an older adult admitted to a care facility after surgery may devise a new or more realistic strategy related to their recovery, such as integrating new foods within their diet, devising some type of exercise plan or regimen to follow, or setting a date to return home.

Once the older adult has engaged in goal selection, Baltes (1997) posited that they will likely pursue optimization. Optimization entails the application and engagement of behaviors necessary to reach selected goals and achieve improved adaptative capacity or plasiticity. In effect, older adults may pursue desirable outcomes by seeking cultural-based knowledge, committing to a particular goal or set of goals, engaging in practice, or using personal energy or effort to meet an established goal. As an example, an older adult who devised an exercise plan or regimen after surgical recovery may commit to such plan by attending physical therapy sessions or putting in extra time or effort practicing a particular form of exercise.

Baltes (1997) further proposed that older adults who optimize their goal commitments will eventually experience compensation, or the redirection of loss into a gain or set of gain which can be better regulated and managed for sustained plasticity or performance. Baltes (1997) suggested that optimization of selected goals allows for overcoming negative transfer or incongruency among one’s goals. This allows the older adult to direct loss in way that reduces varying constraints that may have previously limited the ability to perform or function on some level. Baltes (1997) hypothesized that compensation comes in varied forms. To illustrate, an older adult who demonstrates an improved ability to walk, maintain balance, and independently perform varying activities of daily living (e.g., taking medications, dressing and undressing, getting in and out of bed) after surgery may be deemed by their physician as safe and appropriate to return home, where the older adult can continue to age-in-place.

Although SOC Theory provides a theoretical basis relative to addressing how older persons adapt and remain resilient to developmental losses, some critics have noted the theory to be somewhat reductionistic and weak relative to explaining individual differences in resilience. Others have further noted that this creates problems relative to application of measurement and assessment within group settings, such as work environments and residential or community settings where multiple people with different skills and abilities interact on a daily basis.

Established Adulthood: A New Contemporary Life-Span Theory

Since Erik Erikson first released his eight-state theory of human development in 1950, substantial progress has been made relative to advancements surrounding theoretical understanding of adult human development. According to Mehta and colleagues (2020) most theoretical conceptualizations have primarily focused on the children under age 18, the emerging adult years (18 to 29 years), and the developmental periods of mid-life and later adulthood. In addition, there has long been philosophical disagreement as to when mid-life begins and ends as a life-stage or developmental period of life. Conclusive evidence stemming from longitudinal explorations of the Midlife in the United States Longitudinal Study (MIDUS) has indicated that mid-life represents a new crossroad between continued developmental growth and initial decline (Lachman et al. 2015). In fact, there is some agreement that the unique developmental characteristics involving gain and loss occur when persons are 45 to 65 years of age (Brim et al, 2004; Ryff et al., 2011). In turn, one developmental period of aging in adult life has remained overlooked and received limited theoretical attention. According to Mehta et al. (2020) this developmental period of life concerns persons who are age 30 to 45 years. This is a stage of life during which persons are extremely focused on balancing career development and personal achievement, while fulfilling the responsibilities of an intimate or romantic partnership, raising children, and even caring for an older parent. Therefore, Mehta et al. (2020) have advocated for a new theoretical conceptualization covering the period of life referred to as “established adulthood.” Established adulthood is a developmentally unique period and pre-cursor to middle age. Unlike mid-life adults who are more likely to be experiencing biopsychosocial changes that require maintenance of gains, peaks, plateaus, and losses; established adults tend to encounter relative stability in personal gains involving career expertise, becoming new parents and raising young children, and meeting the demands of aging and mostly independent older parents. Furthermore, established adulthood is a developmental period during which humans experience the benefit of good health, enhanced use of cognitive and intellectual abilities, and increasing positive emotions. However, established adulthood involves what Mehta et al. (2020) referred to as the “career-and-care-crunch.” Although established adulthood may be assumed to be a rather mundane, developmental tasks during this period of life are far from routine. Established adulthood brings new developmental challenges surrounding work-life balance, while maintaining one’s sense of personal identity and variations in personal (internal) and cultural (external) beliefs, values, or attitudes that can improve as well as impede the extent to which established adults are adequately meet work demands and the family matters (see Table below).

| Domain | Emerging Adulthood | Established Adulthood | Mid-Life |

|---|---|---|---|

| Romantic Relations | Formation/Evolving | Long-Term | Long-term |

| Work/Career | Information gathering Skill formation Multiple jobs |

Commitment Building expertise Responsibility Stability |

Seniority Recognized expert Legacy building Building |

| Family Caregiving | Child free Launch from home Parental interdependence |

Childbearing decision Birth of first child Young children Aging parents |

Empty nest Older children Advising/supporting children Caring for aging parent due to declining health or death |

| Physical Health | Risky behaviors Unhealthy diets Inconsistent sleep High stamina Strong immunity High self-rated health |

Fewer risk behaviors Healthy diets Sleep adjustments due to young children Strong immunity Initial decline in metabolism High self-rated health |

Metabolic syndrome risk Obesity risk Increased risk of heart disease and cancer Diminishing immunity Decrease in self-rated health |

| Cognition/Intellect | Gaining cultural knowledge High fluid intelligence Fast processing speed Developing problem-solving skills |

Declining knowledge level Intellectual expertise Reduced processing speed Increasing cultural knowledge Problem creation and solving |

Domain-specific knowledge Recognized expertise Noticeable declines in processing speed Increased cultural knowledge Problem anticipation Wisdom development |

| Emotional Well-being | Low Positive Affect ------------------------------> High Positive Affect | ||

Sociological Theories of Aging

The Kansas City Studies of Adult Life represented the foundational theoretical root of social gerontology (Hendricks, 1994). The original aim of this study was the bridge multidisciplinary theoretical thinking across disciplines such as sociology, psychology, and human development in order to create a stand-alone social aging theory. The Kansas City Studies originated out of the University of Chicago and was conducted from 1952-1963 through a series of longitudinal interviews and surveys with middle aged adults. These efforts resulted in three classical and sociological-based theories of aging and development which any novice-learner of gerontology should be aware. These theories include:

- Disengagement Theory (Cumming & Henry, 1961): Postulates that aging involves a mutual withdraw or disengagement between the older adult and the social or cultural system to which that individual belongs. This withdraw or disengagement is considered socially normative and expected and requires that the older adult abandon or assume different social roles in preparation of giving the younger generation social opportunity, as well as allowing the older adult greater flexibility in using one’s remaining time to engage in contemplation, solitude, or attending to other worthy efforts central to martial and family relations or preparation for death.

- Activity Theory (Havighurst, 1961; Havighurst, Neugarten, & Tobin, 1968): Proposes that aging is a more positive experience when adults remain socially engaged and active as they become older. Social engagement is hypothesized to slow or delay the negative aging processes, as well as enhance life satisfaction and quality of life. As an antithetical response to disengagement theory, it was believed that older adults do not disengage or remove themselves from society, rather they continue to maintain on-going personal relationships and adopt new social roles through activities which they may not have been able to fully engage due to prior adult social obligations, such as employment, civic responsibility, or child rearing. Activity further posits that older adults challenged by role loss substitute alternative roles or activities in order to remain social integrated and connected.

- Continuity Theory (Atchley, 1971; 1989): Details an extension of activity theory by proposing that older adults maintain continuity in lifestyle pursuits by adapting and preferring socially and emotionally fulfilling roles and activities connected to their past lived experiences. This process was theorized to reflect internal psychological structures reflecting the older adult’s personality, perceptions, and beliefs, as well as external social influences including the family system, social network, and community in which the older adult receives gives and receives support for further maintenance of their self-concept and preferred lifestyle activities and pursuits.

Alternative theoretical perspectives surrounding ageism involve the interaction between race/ethnicity and gender. For instances, the double-jeopardy hypothesis posits that being an older adult member of a racial and ethnic minority population presents a double-disadvantage due to the interactive effect of being old as well as being a person of color (Dowd & Bengtson, 1978; Ferraro & Farmer, 1996). Thus, the combined effect of occupying two potentially socially stigmatized statues has a greater negatively combined effect than only maintaining single social status. For example, being older can contribute to increased disparities in socio-economic stability, increased risk of stereotyping or discrimination, and diminished successful aging potentials; however being older as well as identifying as a woman of color further exacerbates age-associated disadvantages above and beyond one’s racial or ethnic identity. King (1988) expanded upon this notion by further coining the theoretical term multiple jeopardy hypothesis, which presumed that one’s identity leading to social prejudice or discrimination can result in multiplicative effects and outcomes. Identification as a older person of color can contribute to increased risk of racism, gender discrimination, and reduce social opportunity or socio-economic affluency which have a negative cumulative impact relative to how well one might age across the life-span. Older individuals who fit into more than one “discriminated-against” category are affected by biases against each of category. For example, women may be subject to ageism and sexism, whereas minority-status women are subjective to the multiplicative impact of racism in addition to ageism and sexism.

However, it is plausible that some older adults may be protected from double or multiple jeopardy situations. The age-as-a-leveler hypothesis theorizes that as people continue to become older and closer to death, age itself overrides all other “ism” experiences (Beckett, 2000; Ferraro & Farmer, 1996; Huisman, 2004). Despite any prior status in life, all older adults become victims of the same social stereotypes no matter their gender, race, or other social characteristics. This can be best demonstrated through an example of socio-economic status. For example, an older white man may have enjoyed advantages relative to climbing the corporate career ladder through adult life which allowed for an accumulation of wealth and greater access to resources while supporting family affluency; whereas an older low-income minority woman may have financially struggled throughout her adult years having to work two to three jobs and find accessible social and community resources or government assistance to help support raising multiple children. Although the man may have enjoyed many years of social advantages above and beyond the woman when younger, that age-as-a-leveler hypothesis proposes they are now regarded by society as being old and dependent; thereby having an equally low social ranking and status because they are no longer younger. Thus, there is only a single jeopardy process of ageism rather than a combination of “isms” operating relative to social status and old age.

Another alternative theoretical perspective includes the inoculation hypothesis or the viewpoint that older adults who experience multiple jeopardy may actually fare better in old age than those who have maintained a high social standing and therefore experienced little to no ageism (Kite & Johnson, 1988; Levy & Banaji, 2002; Montepare & Clements, 2001; Zebrowitz, 2003) . The inoculation hypothesis posits that older persons of color and those representing ethnic minorities, particularly women, have endured years of exposure to discrimination, stereotyping, and prejudice. In turn, they have learned how to adopt strategic and innovative ways of coping, developed a higher tolerance level to withstand negative social experiences, and have managed to become immune to the impact of ageism compared to their older counterparts. Thus, upper-income white men may actually find social stereotypes, discriminatory acts, and ageist opinions more challenging and difficult to confront and accept in old age compared to low-income minority women, who have endured many years of being treated as a less respected and desirable member of society. Depending on each person’s social experience, the man’s long-standing social privilege may also benefit access to economic resources by which to temporary draw upon for protection against a newly acquired lower social status by default of his age. However, this may still not be enough to provide long-term protection against the immediate impact of ageism, which will eventually erode the man’s tolerance and ability to cope and adjust to ageist encounters much faster had he endured a lifetime of social discrimination and stereotypes. The inoculation hypothesis is believed to explain why many low-income minority women may thrive better in later adulthood relative to health, longevity, and well-being than their white male and female counterparts.

Ecological Systems Theory

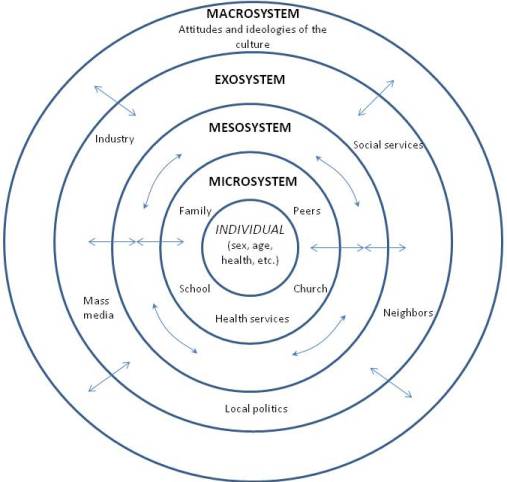

Bronfrenbrenner (1977; 1995) believed that human aging and developmental is shaped by a complex and interactive set of larger social forces and institutions, such as the family, schools, religion, culture, and the passing of time. Bronfenbrenner advocated for an ecological systems perspective to enhance understanding of how different environmental contexts simultaneously impact the development of all humans. According this theoretical approach, there are five ecological systems in place that operate across the life-span As individuals, we are embedded within and surrounded by the dynamic operations of all five systems which determine how we age and develop in space and across time (Bronfrenbrenner 1977; 1995; Bronfrenbrenner & Ceci, 1994; see Figure 3.2). These systems include:

- Microsystem includes the individual’s setting and those who have direct, significant contact with the person, such as parents and siblings. The input of those is modified by the cognitive and biological state of the individual as well. These influence the person’s actions, which in turn influence systems operating on him or her.

- Mesosystem includes the larger organizational structures, such as school, the family, or religion. These institutions impact the microsystems just described. The philosophy of the school system, daily routine, assessment methods, and other characteristics can affect the child’s self-image, growth, sense of accomplishment, and schedule thereby impacting the child, physically, cognitively, and emotionally.

- Exosystem includes the larger contexts of community. A community’s values, history, and economy can impact the organizational structures it houses. Mesosystems both influence and are influenced by the exosystem.

- Macrosystem includes the socio-cultural elements, such as domestic and global economic conditions, geopolitical conflicts, technological trends, cultural values, religious and spiritual philosophies, laws and principles, and public policies that govern social and cultural operations.

- Chronosystem is the historical context in which these experiences occur. This relates to the different generational time periods previously discussed, such as the baby boomers and millennials.

Despite its comprehensiveness, Bronfenbrenner’s ecological system’s theory has been criticized by critics as not easy to use. For instance, accounting for all the different contextual influences makes it difficult to research and determine the impact of all the different contextual variables that shape human aging and development (Dixon, 2003). Consequently, developmentalists and gerontologists have not fully adopted this approach. Yet, they recognize the importance ecology relative to how humans age, grow, and mature in time.

Life Course Theory

Researchers form the Rochester Adult Longitudinal Study have cited five routes or “life pathways” that individuals encounter when navigating the human life course (Constantinolple, 1969; Whitbourne & Waterman, 1979; Whitbourne, 2010; 2020; Whitbourne, Sneed, & Sayer, 2009; Whitbourne, Zuschlag, Elliot, & Waterman, 1992). First, individuals follow a straight and narrow pathway, whereby they seek to avoid any dramatic life events that might change the current course of their life. Such individuals maintain a philosophy of “if it’s not broken; then don’t fix it.” Therefore, persons on the straight and narrow path of life are engage in consistent and routine patterns of lifestyle choices and decisions resulting in limited to no deviation. Simply put, they are content with the way life is and do very little to change it. Second, persons follow a meandering life pathway. This life pathway represents an antithesis of the straight and narrow in as much that there are some persons who may not be happy or satisfied with the course of their life. Such persons often change their minds and interests and fail to really settle on core direction life should take. Instead, they spend much of their life course engaging in a variety of life commitments such as moving to new geographical locations, trying new careers, and pursuing new hobbies and other interests. For these individuals, it might be said that “variety is the spice of life.” Third, some persons enjoy an authentic life pathway or trajectory the includes a series of various changes in order to improve one’s sense of identity and meaning, enhance personal growth, or personal security. As an example many persons enter the second-half of life often enter into an authentic trajectory, whereby they may choose to go back to school to receive specialized training or pursue a different college degree or lifelong learning program in order to embark upon a different or more personally fulfilling career, improve work-life flexibility for purposes of spending more time in preferred social role pursuits (e.g., grandparenthood, volunteerism, travel), learning a whole new set of life-skills, or saving and financially planning for one’s health and retirement. Fourth, there are persons who also following a triumphant life pathway, or life course trajectory whereby they learn to cope and overcome a variety of early life traumas or set-backs across the life course, such as being abused as a child, exposure to warfare, marital conflict and divorce, or death of a child or spouse. Such persons do not necessarily seek to change the course of their life. Rather, they learn to develop favorable strategies vital to seeking and finding supportive resources, as well as adopting positive resolutions involving the traumatic adversities of life. Despite lifetime exposure to negative events, such persons adopt a more optimistic perception of the past and hopeful view of the future. The real triumph comes when they are better able to handle the difficult moments and developmental challenges of aging during the later years.

Life Course Theory provides a framework for theoretically understanding the course of life. Elder (1998) proposed that that human development and aging occurs across a socio-historical trajectory. Of central importance is the concept of human agency, or an individual’s timing, will, and capacity to make decisions and choices relative to directing, determining, and deriving personal meaning from the socio-cultural environment, as well as directing the course of life within the socio-historical constraints and circumstances during which individuals and populations of people age and develop.

To give explanation of the human life course, Elder (1998) framed the “Four T’s” of the human life course. The Four T’s represented four basic concepts by which the life course perspective is framed. These concepts include:

- Trajectories: long-standing developmental patterns of stability and change reflecting advantage(s) and disadvantage(s) in human agency (e.g., decision to marry, preferred line of work, raising a family)

- Transitions: Momentary periods along the life course representing normative life experiences and expected change(s) along the developmental continuum (e.g., high school graduation, voting, marriage, work, retirement)

- Turning points: Transitions marked by substantial and sometimes life-altering change(s) to the life-course trajectory (e.g., divorce, unemployment, death)

- Timing: Socio-historical circumstances reflecting individual and collective encounters of “on-time” versus “off-time” life events which delay or accelerate stability or change (e.g., economic growth; state and national elections, supreme court decisions; climate change; warfare)

Expanding upon the Four T concepts, Elder (1998) recognized that these concepts incorporate three key variables necessary for understanding human aging and development. These variables include: Age (Individual-level chronology and social experience); Cohort (Collective and shared social experiences of persons born the same year or within same period of years) and; Period (Historical timing of social experiences relative to onset, progression, duration, and ending). Taking these variables into account, Elder (1994; 1998) elaborated upon the Four T’s concept by positing five essential principles of the human life course.

Principle 1: Age-Stage

According to life course theory, chronological timing within development stages or periods of life shapes how individuals perceive and make meaning out of life (Elder, 1999; Elder & Conger, 2000; Settersten, Elder, & Pearce, 2021). More specifically, Elder (1998; 1999) theorized that the age and developmental stage during which we encounter various socio-historical events shapes our developmental outcomes later in life. Elder (1998) referred to this process as the age-stage principle. To illustrate this principle, Elder (1998) originally reported evidence pertaining to development outcomes of adults who experienced the Great Depression at age 10. Most notably, children during the Great Depression had to develop specific behavioral routines to maintain a sense of self-worth as well as feeling of industry or “doing good.” When examined as adults later in life, these same children recalled that they had to often find work to economically support their family, and in some cases they were designated as the head of the household in the absence of a father who was away actively seeking work (Elder, 1999; Settersten et al., 2021). Elder (1999) noted that such critical developmental experiences during childhood shape the way persons behave, cope, and develop in later in life. Among children of the Great Depression, many commonly adopted minimalist living standards such as recycling, restoring, and reusing various products of living, engaging in frivolous consumer spending favoring saving one’s money for a rainy day or potential future economic collapse, as well as having the knowledge to complete a variety of life skills or what is commonly referred to as being a “jack-of-all-trades and master of none.” Thus, our chronological age and the developmental stage at which we are exposed to social and historical experiences differentially shape our behaviors, routines, preferences, beliefs, and attitudes later in life. Similar evidence based on the life course of children who experienced the Iowa family farm crisis of the 1980’s has demonstrated further replication of the age-stage principle (Elder & Conger, 2000). Bengston and Kuypers (1973) referred to the development link between age and stage across family members as a phenomenon as the “intergenerational stake,” or a process by which persons of varying ages and stages express perceptual and behavioral differences unique to their own development. While children seek to secure a sense of individuation from parents through autonomy and productivity; their adult parents seek to maintain a sense of social interconnection through a demonstration of care, commitment, and legacy toward the next generation. Such processes in childhood as well as adulthood are essential determinants of how both child and adult will address the domains of life (e.g., family, work, economics, religion) in old and very old age.

Principle 2: Linked-Lives

Similar to Brofrenbrenner’s ecological systems approach, Elder (1994; 1998; 1999) believed that humans are ecologically embedded within social settings. Most important, our social networks, relationships, and interactions are interconnected across multiple social contexts. At a very basic level, we are share an interconnection to family at birth. Whether we are born to a single-parent or two married parents, our birth right automatically makes an interconnected member of a family unit and system in which we are have direct and indirect kinship ties including but not limited to grandparents, siblings, cousins, aunts and uncles. Life course theory acknowledges that family systems further connect individual members to the broader ecology of the social system via the neighborhoods in which one may live, work, and play; the schools which one may attend and are educate; the churches, synagogues, or mosques of which one may have membership to practice faith; or even the local, county, state, or national regions in which the individual may come to engage in various cultural customs or agree or dissent to obey laws and policies (Elder, 1998; 1999; Elder & Conger, 2000). However, Elder (1998; 1999) also theorized that each of us is also bonded to a multitude of different persons with whom we may share or not share commonalities in our development. Some of these persons may remain complete strangers for the rest of our lives, whereas others will be considered acquaintances or life-long family and friends. Elder (1994; 1998; 1999; Elder & Conger, 2000; Settersten et al., 2021) noted that all humans are born into and represent a particular birth cohort of persons with whom they collectively adopt, share, and witness similar socio-historical events across the life course. We are not only individual members linked to a family. Instead, we are individual members linked to a greater collective membership of society by virtue of the year or historical period in which we may be born. Being a member of such group means that we develop together rather than alone. Essentially, our lives are linked to people whether as an individual connected to a generation, or family and blood-related social ties; or an individual who by default enters into a collective membership or cohort of others who share the same birth year. Regardless, Elder (1994; 1998; 1999) postulated that developmental course of human life is influenced by the persons with whom we are linked immediately from birth, and with whom we may affiliate by virtual of being born at a particular point in time and history. Such social connections further shape our social development into old and very old age relative to our preferences, beliefs, attitudes and alignments involving others with whom we will gravitate as well as seek care and assistance.

| COHORT | SHARED HISTORY | SHARED BELIEFS | SHARED IDENTITIES |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRADITIONALISTS (1925-1945) |

• Great Depression • World War II • Post-War growth |

• Work for the common good • Age earns respect • Skill advancement • Live within means |

• Loyal • Dependable • Straight-forward • Tactful |

| BABY BOOMERS (1946-1964) |

• Cold War • Vietnam War • Civil Rights • Watergate |

• Wealth through sacrifice • Work hard; play fair • Focus on teamwork • Peace, love, and equality |

• Competitive • Optimistic • Workaholic • Team-oriented |

| GENERATION X (1965-1980) |

• Arms Race • Aids Epidemic • Fall of Berlin Wall • Dot-com boom |

• Diversity • Work-life flexibility • Practicality and efficiency • Technology progression |

• Flexible • Skeptical • Independent • Informal |

| MILLENIALS (1981-2000) |

• Columbine shooting • 9/11 • Internet |

• Personal growth • Work-life-balance • Sustainability • Social responsibility |

• Civic engagement • Open-mindedness • Competitive • Achievement-oriented |

| GENERATION Z (2001-2020) |

• Iraq/Afghanistan War • Great Recession • COVID-19 • Smart/AI Tech |

• Social justice • Diversity, Equality and Inclusion • Individuality and self-identity • Innovation and creativity |

• Progressive • Global • Autonomy • Tech dependent |

Principle 3: Cycle-of-control

Life course theory posits that most persons seek control over the direction and outcome of their life course (Elder, 1994; 1998; 1999). However, the trajectory of the individual life course development depends upon two types of control (Elder, 1998; Elder & Conger, 2000; Settersten et al., 2021). First, some persons may feel a high degree of personal or internal control over the direction of their life. Elder (1998) referred to this as the internalization of control, or individual perception or internal locus of control belief that the timing and occurrence of life experiences and events is due to the choice, decisions, or actions of the person. In other words, persons with an internal locus of control believe they largely responsible for current and future failures and success in life. In turn, persons with a strong internalization of control view negative life experience, difficulty, or challenge as something that can be easily corrected or resolved by one’s own behavioral actions and efforts. Second, some persons may feel a high degree of external control over the trajectory of their life. Elder (1998) referred to this as the externalization of control, or the individual perception or external locus of control whereby the timing, circumstances, and outcomes of one’s life are due to chance, luck, fate, or something greater than one’s self. Thus, persons who express an externalization of control often less responsible for the trajectory of life. They may feel that certain situations, circumstances, or happenings in life are beyond their control, skills, or abilities. Ultimately, nothing can be done to change one’s current or future life experience. Instead of taking corrective action to change the direction of life, a externally controlled individual may elect do to little or nothing about the situation. If it turns out something good or bad, as well as easy or difficult will result in life, then it was likely due to someone or something else beyond the person. A classic example of the cycle-of-control in the life course involves the impact of a natural disaster. A natural disaster can be a life-altering event that sets the individual life course on a varying trajectory. In the aftermath of a natural disaster, it is not uncommon to hear two contrasting responses from those who experienced the same devasting event. First, there are those who tend to be internally directed. Such persons take control of the situation by immediately and independently cleaning-up, rebuilding, and trying to regain some type of normalcy to everyday life. In some cases, persons with a high sense of internal control might admit that they are not going to sit around and await until local emergency management officials or government assistance has arrived before they begin to “build again.” Second, there are those who may be externally directed. These persons may be somewhat resistant at first take immediate action. Instead, they make take a moment to reflect upon the aftermath of the disaster, contemplate their own survival, or even say a prayer. Such persons may admit that the event was an act of nature, or event further suggest something beyond oneself, whether God or some other supernatural power or entity, had provided for their safety and continued survival. In some instances, such persons may admit that they are going to “wait and see” what happens before picking up the pieces.

Principle 4: Situational imperative(s)

There moments in the life course that demand individuals immediately engage human agency. The unpredictability of life can translate into situations where quick decision-making and choices need to be made. Doing otherwise is an imperative matter of life and death. Elder (1998) referred to such situations across the life course as situational imperatives, or life-situations that require use of human agency to resolve and the consequential or potential threat of harm due to a life-occurring stressors. In some cases, situational imperatives can be thought of as being like a “fork in the road” of life. There are times during the course of life, we as humans may be forced to take action and make decisions that could potentially be life-changing. Any decision, whether informed or uninformed, will potentially have good as well as bad consequential effects on our development as we continue to age through life. You might say situational imperatives are like having a “damned if you do; damned if you don’t” compromising moment in life. For many, the question may be: What do I do? Dannefer (2003) elaborated on Elder’s (1998) situational imperative concept by proposing the Cumulative Advantage/Disadvantage (CAD) theory, which posits that interindividual divergence in late-life development emerges from lifetime decisions involving domain-oriented experiences in marriage, family, work, health, or socio-economics. Failure to act or resolve the divergent life situations may imperatively do harm and can significantly and negatively alter the trajectory of the life course to the point of contributing to the accumulation of disparities. For example, addictive behavior may contribute to marital conflict, which then leads to the risk of divorce and possibly unemployment and financial setbacks. Over time, this can lead to negative developmental outcomes in biological, psychological, and social functioning. However, positively engaging one’s human agency to resolve imperative life situations helps offset the deleterious nature of domain-oriented stressors contributes to advantageous developmental outcomes. Similar to the example above, a person may seek treatment for addiction, which helps subside marital conflict as well as reduces the risk of job termination resulting in financial stability. According to Elder (1998), the timing of imperative situations is essential to making sound decisions. It is important to note that situational imperatives can arise as both (1) “off-time” experiences or what might be termed unexpected or developmentally non-normative stressors (e.g., being married, remarried, and divorced multiple times before age 30); and (2) “on-time” experiences or expected and developmentally normative life conditions or situations (e.g., high school graduation, followed by work or college, which is then followed by employment, marriage, and raising a family).

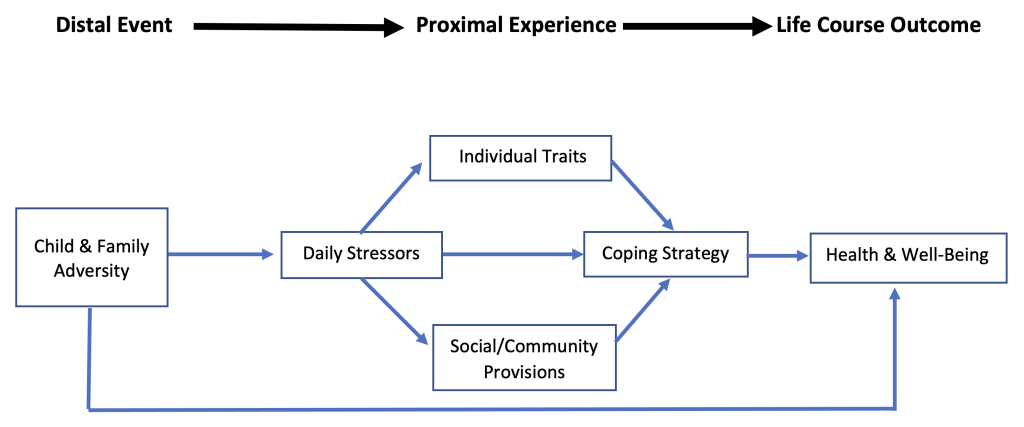

Principle 5: Accentuation

Elder (1994; 1998) designated accentuation as a fifth and final principle of life course theory. This principle emphasizes the link between early life experiences later-life developmental outcomes. However, the magnitude (e.g. strength/severity), direction (e.g., negative/positive) or significance (e.g., meaning/non-meaning) of this relationship is only positively or negatively robust to the extent that the individual can access and favorably use individual psychological traits (e.g., identity/personality, cognition, will, and purpose) and social and community provisions (e.g., support, economic, religious) resources. For example, a mid-life adult who was physically abused as a child might directly anticipate being challenged by post-traumatic stress symptoms and negative memories of the past. In the near-absence of psychosocial resources, the severity of these symptoms and memories would likely be greater and more negative. Yet, if the person is able to access and use psychosocial resources effectively the severity of such symptoms and memories of one’s past might potentially diminished or be reduced during later life. Martin and Martin (2002) proposed a similar model which illustrates accentuation (See Figure 3.3). Designated as the Developmental Adaptation Model (DAM), Martin and Martin (2002) posited that adverse child experiences and family adversity represent two of the most salient and distal early-life experiences detrimental to successful late-life development. Such early experiences contribute to proximal life experiences and everyday access and use of psychosocial resources. In turn, this proximal mechanism contributes to adaptative behavior in the form of coping strategies which can help improve biological, psychological, or social development in old age. Recent evidence suggests that DAM provides a sound conceptual framework for modeling, testing, and theorizing life course processes involving accentuation among middle aged and older adults with a history of child and family adversity (Randall & Bishop, 2019; Randall & Bishop, 2022).

Key Takeaways

Important concepts from this chapter include, but are not limited to, the following:

- In addition to genetic processes, aging also involves psychological dimensions as well as sociological dimensions

- Erik Erikson's stages of development help explain common connections that many people share based on their age range

- Joan Erikson's Ninth Stage helps explain the unique needs and considerations of older adults

- Gerotranscendence consists of three dimensions that are primarily observable among older adults: the Cosmic dimension, the Selfing dimension, and the Social and Personal Relationship dimension.

- Paul Baltes's holistic approach to gerontology involves the study of aging as a holistic process

- Sociological Theories of Aging primarily involve Disengagement Theory, Activity Theory, and Continuity Theory

- Ecological Systems Theory involves five key systems: Micro, Meso, Exo, Macro, and Chrono

- Live Course Theory provides a framework for theoretically understanding the entire course of life, including the four T's of Trajectories, Transitions, Turning Points, and Timing.

- Elder's five essential principles of the human life course are Age-Stage, Linked Lives, Cycle of Control, Situational Imperatives, and Accentuation.

References

Atchley, R. C. (1971). Retirement and leisure participation: Continuity or crisis? The Gerontologist, 11(1), 13-17. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/11.1_Part_1.13

Atchley, R. C. (1989). A continuity theory of normal aging. The Gerontologist, 28(2), 183-190. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/29.2.183

Baltes, P. (1987). Theoretical propositions of life-span developmental psychology: On the dynamics between growth and decline. Developmental Psychology, 23(5), 611-626. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0012-1649.23.5.611

Baltes, P. (1997). On the incomplete architecture of human ontogeny: Selection, optimization, and compensation as foundation of developmental theory. American Psychologist, 52(4), 366-380. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0003-066X.52.4.366

Becket, M. (2000). Converging health inequalities in later life-An artifact of mortality selection. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 41, 106-119. doi: 10.2307/2676363.

Brim, O. G., Ryff, C. D., & Kessler, R. C. (2004). The MIDUS National Survey: An Overview. In O. G. Brim, C. D. Ryff, & R. C. Kessler (Eds.), How healthy are we?: A national study of well-being at midlife (pp. 1–34). The University of Chicago Press.

Bronfrenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513-531. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

Bronfrenbrenner, U. (1995). Developmental ecology through space and time: A future perspective. In P. Moen, G. H. Elder Jr., & K. Lüscher (Eds.). Examinging lives in context: Perspectives on the ecology of human development (pp. 619-647). American Psychological Association. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/10176-018

Bronfrenbrenner, U. & Ceci, S. J. (1994). Nature-nurture reconceptualized in developmental perspective: A bioecological model. Psychological Review, 101(4), 568-586.

Cowgill, D. O., & Holmes, L. D. (Eds.). (1972). Aging and Modernization. New York: Appleton-Century Crofts.

Constantinople, A. (1969). An Eriksonian measure of personality development in college students. Developmental Psychology, 1(4), 357-372.

Cumming, E. & Henry, W. E. (1961). Growing Old: The process of disengagement. New York: Basic.

Darrell, A., & Pyszczynski, T. (2016). Terror management theory: Exploring the role of death in life. New York, NY: Routledge.

Dowd, J. J., & Bengtson, V. L. (1978). Aging in minority populations: An examination of the double jeopardy hypothesis. Journal of Gerontology, 33(3). 427-36. doi 01.1093/geronj/33.3.427.

Elder, G. H., Jr. (1994). Time, human agency, and social change: Perspectives on the life course. Social Psychology Quarterly, 57 (1), 4-15.

Elder, G. H., Jr. (1998). The life course as developmental theory. Child Development, 69 (1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06128.x

Elder, G. H. (1999). Children of the great depression, 25th anniversary edition. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis.

Elder, G. H., & Conger, R. D. (2000). Children of the land: Adversity and success in rural America. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Erikson, E. H., & Erikson, J. M. (1997). The life cycle completed. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Ferraro, K. F., & Farmer, N. M. (1996). Double jeopardy, aging as a leveler, or persistent health inequality? A longitudinal analysis of white and black Americans. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 51(60), S319-328.

Flamion, A., Missotten, P., Jennotte, L., Hody, N., & Adam, S. (2020). Old-age related stereotypes of preschool children. Frontiers in Psychology, 28, Vol. 11-2020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00807.

Havighurst, R. J. (1961). Successful aging. Gerontologist. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/1.1.8

Havinghurst, R., Neugarten, B. & Sheldon T. (1968). In B. Neugarten (Ed.). Patterns of Aging in Middle Age and Aging, pp. 161–172. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press

Huisman, M. (2004). Socioeconomic inequalities in mortality among elderly people in 11 European countries. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 58, 468-475. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.010496.

Kennison, S. K., & Byrd-Craven (2018). Childhood relationship with mother as a precursor to ageism in young adults. Current Psychology. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12144-018-9838-2

King, D. K. (1988). Multiple jeopardy, multiple consciousness: The context of a black feminist ideology. Signs, 14(1). https://doi.orgg/10.1086/494491.

Kite, M. E., & Johnson, B. T. (1988). Attitudes toward older and younger adults: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 3, 233-244.

Lachman, M. E., Teshale, S., & Agrigoroaei, S. (2015). Midlife as a pivotal period in the life course: Balancing growth and decline at the crossroads of youth and old age. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 39, 20-31. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0165025414533223

Levy, B. R., & Banaji, M. R. (2002). Implicit ageism. In T. Nelson (Ed.). Ageism: Stereotypes and prejudice against older persons (pp. 49-75). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Levy, S. R. (2018). Toward reducing ageism: PEACE (positive education about aging and contact experiences) model. The Gerontologist, 58(2), 226-232. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw116

Martin, P., & Martin, M. (2002). Proximal and distal influences on development: The model of developmental adaptation. Developmental Review, 22 (1), 78-96. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1006/drev.2001.0538

Mehta, C. A., Arnett, J. J., Palmer, C. G., & Nelson, L. J. (2020). Established adulthood: A new concept of ages 30-45. American Psychologist, 75, 4, 431-444.

Montepare, J. M., & Clements, A. M., (1988). “Age schemas:” Guides to processing information about the self. Journal of Adult Development, 8, 99-108.

Randall, G. K., & Bishop, A. J. (2021). Testing a portion of the Oklahoma aging inmate forgiveness model. Journal of Religion, Spirituality, & Aging, 33(4), 430-447. https://doi.org/10.1080/15528030.2021.1891187

Randall, G. K, & Bishop, A. J. (2022). Forgotten variables and older men in custody: Negative childhood events, forgiveness, and religiosity. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 94(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/00914150211031892

Ryff, Carol D., Kitayam, Shinobu, Karasawa, Mayumi, Markus, Hazel, Kawakami, Norito, & Coe, Christopher (2011). Survey of Midlife in Japan (MIDJA), April-September 2008 - Version 2. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR30822.v2

Settersten, R. A. Jr., Elder, G. H. Jr., & Pearce, L. A. (2021). Living on the edge: An American generation’s journey through the 20th century. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Tornstam, L. (2005). Gerotranscendence: A developmental theory of positive aging. New York: Springer Publishing.

Whitbourne, S. K. (2010). The search for fulfillment. New York: Ballantine.

Whitbourne, S. K., Sneed, J. R., & Sayer, A. (2009). Psychosocial development form college through midlife: A 34-year sequential study. Developmental Psychology, 45(5), 1328-1340. doi2009-12605-011[pil] 10.1037a0016550.

Whitbourne, S. K., & Waterman, A. S. (1979). Psychosocial development during the adult years: Age and cohort comparisons. Developmental Psychology, 15(4), 373-378.

Whitbourne, S. K., Zuschlag, M. K., Elliot, L. B., & Waterman, A. S. (1992). Psycosocial development in adulthood: A 22-year sequential study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(2),260-271.

Zebrowitz, L. A. (2003). Aging stereotypes-internalization or inoculuation? A commentary. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B, 58(4), P215-P215. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/58.4.P214