Chapter 1: Introduction

Learning Objectives

After reading through Chapter 1: Introduction, students should know, learn, or be able to do the following:

- Explore How Age Perceptions Impact Well-being: Investigate and discuss how subjective views of age can affect individual aging and human development, considering factors that influence these perceptions and their potential consequences.

- Introduce the concept of successful aging: Break down the three key aspects of Rowe and Khan’s Model of Successful Aging, explaining how these elements contribute to a positive aging experience and analyzing their relevance in contemporary society.

- Examine Real-Life Challenges in Aging: Examine real-world challenges that older adults face, both personally and in society, and critically assess potential strategies to address these issues and improve the aging experience.

- Compare Lifespan and Life Expectancy Concepts: Compare the concepts of lifespan and life expectancy, explaining what they mean and discussing their implications for individuals’ development, lifestyle pursuits, and societal and policy planning.

- Visualize Aging Population Changes: Analyze visual representations, graphs, and charts to help understand and present how the demographics of aging populations are changing over time, and consider how these changes might impact aging in society.

Chapter Outline

- Definitions of Age

- The Middle Age Shift

- The Quest to Age Successfully

- Biopsychosocial Ways of Aging

- Lifespan versus Life-Expectancy

- Contemporary Worldviews on Life-Expectancy and Human Life-Span

- Socio-demographic Realities of Aging

- Joe Rogan Podcast Series with Aubrey de Grey (Futurist Viewpoint)

- Joe Rogan Podcast with David Sinclair (Futurist Viewpoint)

- James Vaupel (Optimist Viewpoint)

- Jay Olshansky (Realist Viewpoint)

- Socioeconomic Demographics

- References

Aging is universal. It impacts all persons regardless of biological sex, gender identity, race, ethnicity, religious membership, geographical location, or political affiliation. It is an undeniable fact that all human beings must age, and all must eventually die. Despite efforts by some who have claimed to have pinpointed the symptoms, discovered an effective intervention and treatment, or found a “cure,” the aging process remains the ultimate mystery of life from conception to death. Yet, most persons show little interest in the topic of aging when they are younger. Why would they? Our society tends to endorse youth, fitness, and vigor which creates a reductionistic and authentic view of developmental maturation, or the process by which humans change, grow, and development across the life-span, as confined to the first few decades of life. This can create a misconception that aging and human development as confined to the first 18 years of life. However, this is not realistic. Humans age and develop from the moment of conception until the moment of final death. Aging is a continuum of short- and long-term developmental change and stability on an intra-individual level or development within or unique to the individual, as well as an inter-individual level of development between persons or unique to populations of people. Such processes coincide and are best demonstrated across three life-span influences including:

- Normative age-graded influences: An age-grade is a specific age group, such as: toddler, adolescent, adult, or older adult. Humans in a specific age-grade share particular experiences and developmental changes.

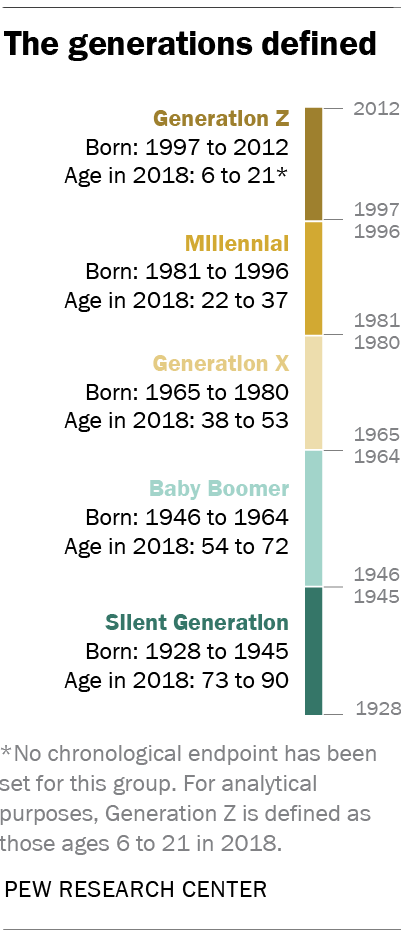

- Normative history-graded influences: The time period in which you are born (see Table 1.1) shapes your experiences. A cohort is a group of people who are born in the same year or around the same period of years in a particular society. These people travel through life often experiencing similar social and historical events and circumstances.

- Non-normative life influences: Despite sharing an age and history with our peers, each of us also has unique individual experiences that may shape our development. A child who loses his/her parent at a young age has experienced a life event that is not typical of that particular age group.

Definitions of Age

Ironically, many persons spend the first 18 years of life longing to be chronologically older or more mature than they are. When you were younger, you probably did not give aging much thought other than the fact that age was only a number. However, there are a variety of ways in which age is defined. For starters, chronological age reflects the amount of time that has passed since a person’s birth expressed in terms of years, months, weeks, or even days. Parents often encourage their newborn infants and toddlers to crawl, walk, speak, or even throw a ball before they may be developmentally ready to do so. Chronological age is a better reflection of maturation relative to the amount of time that has passed since birth than an explanation of true developmental maturation or change.

Chronological age is simply a number and way to demarcate the timing of development across the human lifespan. It is often considered with some level of credibility when we are younger. In the mind of a child, a larger number connotes something bigger, better and of greater meaning or significance. Many young children verbally and behaviorally express what they want to be when they grow-up as demonstrated through pretend play, peer interactions, and behavioral mimicking of adult and parental social roles on the playground. Some young children even express a desire to be “double-digits.” A double-digit birthday carries more value and is indicative of becoming older and more like and the adult one may admire. As children enter adolescence, they may begin to daydream about turning 16 and driving a car. Adolescence is also a developmental period during which children might express an interest in turning 18 years old and legally becoming an adult who vote in public elections, express their identity, and make life choices and decisions independent of parental control, monitoring, or consent. This developmental milestone emerges into an adulting period by which one begins to pursue the rites of adult passage from age 18-25 years. Developmental activities during this period include but not are limited to a variety of life experiences such as turning 21 and becoming legally responsible to drink alcohol, seeking advanced skills and education to build a career, romantically seeking a potential mate for marriage, starting and raising a family, and becoming a socially responsible and contributing member of society.

We spend the first-half of our life wanting to age before our time. Yet, this inner desire for maturation subsides by the time persons reach mid-life. The expression of subjective age or the perception of how individuals view or experience themselves as feeling or being younger or older than their actual age becomes prominent. . This is one of the most rudimentary conceptualizations humans use to gauge how well they are aging. Depending on the day of the week, month, or year, it is possible that you may “feel” older than your chronological age, especially if you are experiencing illness, fatigue, stress, or anxiety. It is also possible to “feel” younger, if you are fully rested, mentally alert, relaxed, and experiencing a feeling of stamina and energy.

Middle aged adults judgements of subjective age is influenced by three other forms of aging:

- Biological age or perceived ability to control one’s rate at which our body ages beyond family heredity and genetic factors relative to the maintenance of a healthy diet and weight, engagement in regular exercise, coping with environmental stressors, or adoption healthy lifestyle behaviors and routines (e.g., avoidance of smoking, limited alcohol intake, sleep habits) that might otherwise help offset or delay the onset and experience of acute symptoms, chronic disablement, or terminal diseases which contribute to the wear and tear of our bodies leading to senesce or death.

- Psychological age or perception of maturity, whether younger or older, in terms of how one feelings emotionally and behaviorally through their decisions, actions, and expression of identity and personality. For instance, an individual experiencing cognitive impairment may be 50 years of age, yet has the mental and behavioral functional capacity of a 10-year-old. However, another 50- year old person might be travelling to new countries, taking courses at college, or starting a new business. Compared to others within our age group, we may be more or less psychologically adaptive to meet or cope with new challenges.

- Social age or the perception of one’s interpersonal interactions, sense of connectedness and belonging, and continuity and discontinuity of life-time contributions relative to meeting socio-cultural expectations within the place(s) and time(s) in which one lives. The socio-cultural environment often reminds mid-life adults whether they have been “on target” or “off target” relative to reaching certain social milestones across the life-span, such as launching children from their home of origin, getting a work promotion, or meeting financial goals for eventual retirement. There are some arguments that social age is becoming less relevant in the 21st century (Neugarten, 1979; 1996). If you notice fellow students in your courses at college or co-workers at your place of work, you might start to notice more and more people who are older than the traditional or anticipated able-bodied adult who is between 18-25 years of age. Similarly, the age at which people are moving away from the home of their parents, starting their careers, getting married or having children, or even whether they get married or have children at all, is changing.

The Middle Age Shift

The developmental processes by which we are influenced help us derive a perception of the aging experience as individuals, as well as collective members within a shared group. This is vital to our intention and motivation to continuing fighting the good fight and aging well into mid-life and beyond. “Life begins at 40” is a common cliché used to describe the mid-life experience. A developmental shift occurs approximately between 40 to 60 years of age during which many persons begin to encounter changes in the biological, psychological, and social well-being. The mid-life period represents the first time many individuals will directly and personally encounter the signs and symptoms of being old. Examples of these experiences include an occasional failure to remember someone’s name, difficulty reading words in a book or on computer screen without reading glasses, scheduling routine physical examinations, blood draws, and preventive health screenings, or having to take time off from work to care for an aging parent. Many middle-aged adults beginning to ask themselves, “Have I done enough?” While some persons may negatively consider mid-life as the gradual “beginning of the end” of life as they know it; others more optimistically view it as “second chance or opportunity in life,” to redeem and more realistically align one’s life ambitions of the past, present, and future. This is often connected to the hope that what we do starting in middle age and into old age will build a legacy for living that others, particularly our closest family members and friends, will remember tomorrow and well into the future.

Middle age brings a heightened level of urgency and new set of concerns relative to how to planning and use one’s remaining time left in life in a timely and effective manner. It is a developmental period in which one must negotiate the realization that there is no turning back the clock to relive and change past life experiences, yet there may still be enough time remaining to redirect, rectify, or redeem one’s life in a way that will bring about an improved sense of personal fulfillment, achievement, acceptance, or contentment without shame, guilt, or regret. Most importantly, mid-life is a developmental period during which many persons start to become increasingly cognizant of their own aging process and eventual mortality in lieu of on-going daily hassles and life stressors. In turn, middle aged adults are often referred to as the Sandwich Generation due to the fact that most are engaging in dual-processes and social roles of being caught in the middle of multiple family generations or cohorts, such as raising and launching children from the family household, while simultaneously serving as the primary caregiver to an aging parent; or even remaining a productive member of society who goes to work and live life day- in and day-out, while continuing to surviving the social loss and deaths of those within the broader community with whom one may feel socially networked or emotionally connected.

The Quest to Age Successfully

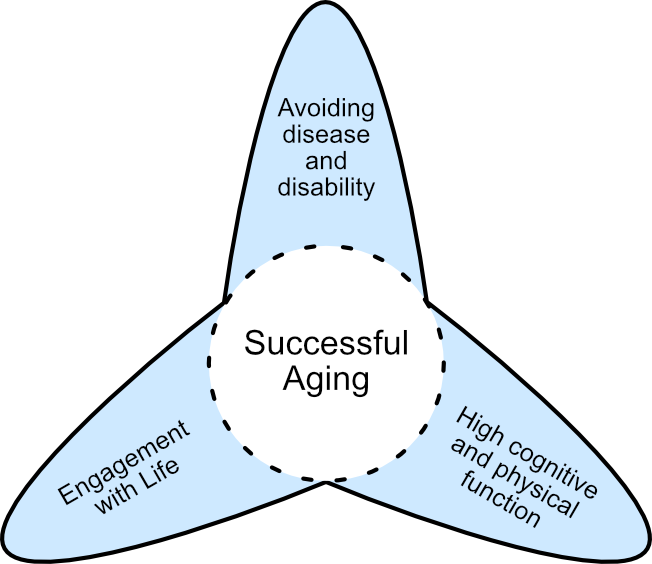

Some might consider middle age as “the make or break” developmental period of life, yet as the saying goes “when the going gets tough; the tough get going.” While some middle-aged adults will find it easy to attribute blame for recent and on-going deficits in biological, psychological, or social functioning and thus do little to improve their well-being, many others will turn to the clinical experts, practitioners, and even family members for assistance with one question in mind: “How can I age successfully?” The good news is that it is never too late to start aging well. Success is within the eye as well as the reach of the beholder. Like most matters in life, we should not expect success, let alone the aging process, to come easy. Those exiting the middle adult years and entering late adulthood are destined to experience both failure and triumph. We may not have taken proper care of our bodies, challenged ourselves mentally, or gravitated toward or maintained positive social relationships or meaningful social roles earlier in life. However, our failures earlier in life are vital to navigating our way toward success during middle adulthood, through late adulthood, and event into advanced or exceptional old age. Aging successfully demands that humans continually appraise, adapt, and reutilize their biological, psychological, or social strengths and weaknesses in resourceful yet sustainable ways. According to Rowe & Kahn (1997) there are three main criteria necessary for “successful aging”

These criteria include:

- Minimize risk behaviors that might otherwise contribute to the onset, progression, and costly chronic or long-term care management of disease, disablement, and end-of-life circumstances;

- Maintain high levels of physical and cognitive (e.g., mind-body) functioning

- Remain socially engaged and actively involved in productive and meaningful activities, hobbies, and leisure pursuits

Biopsychosocial Ways of Aging

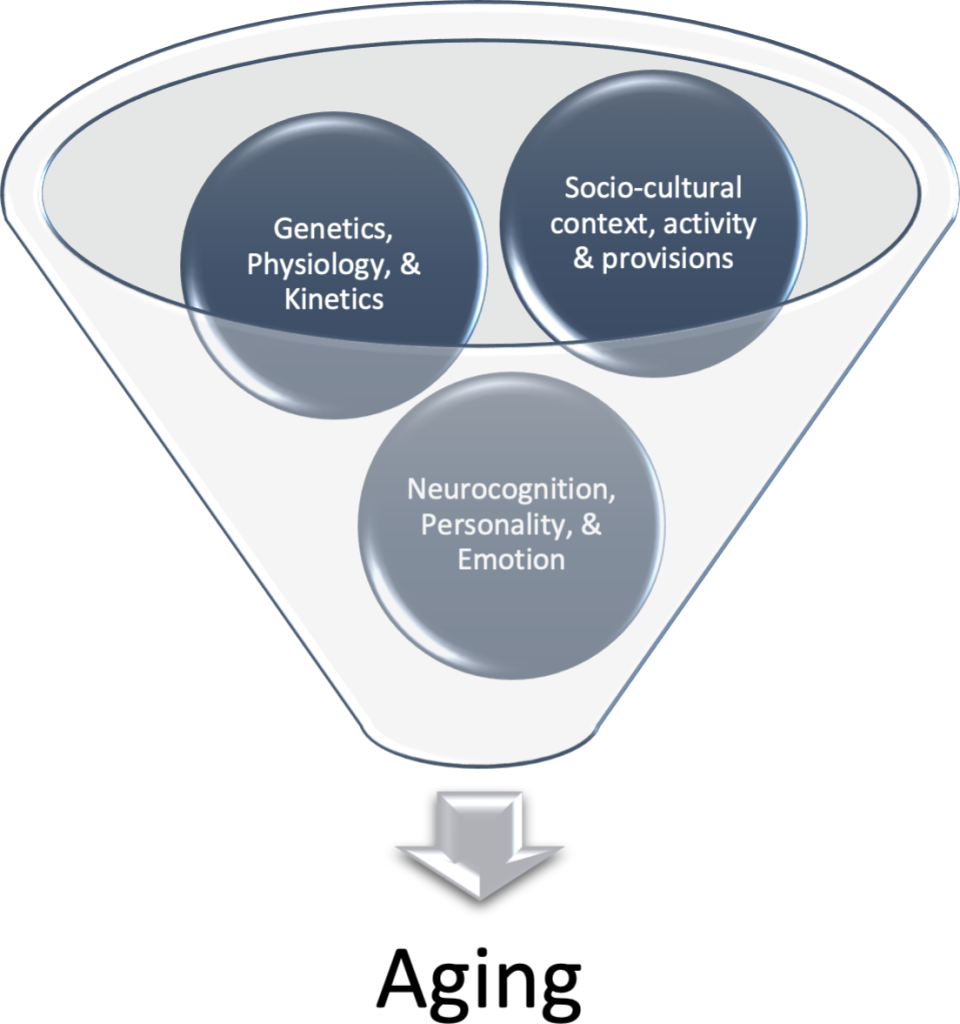

Rowe and Kahn’s (1997) Model of Successful Aging was ultimately a biopsychosocial recommendation or intervening prescription for aging well. It is also a representation of the interconnection and interplay between biological, psychological, and social aging. Together, these processes provide a dynamic framework by which to study and understand the aging and human development. This is often referred to as the biopsychosocial perspective, a view of human development as a dynamic and interactive process involving biological, psychological, and social functioning. Aging is not a simple progression across time. Our bodies undergo biological and physiological changes largely dictated by our genes which may be influence by the environments to which we are exposed. The changes we encounter physically within our bodies influences the extent to which we experience neurocognitive changes involving the way we react to, process, and remember information, as well as express ourselves and regulate emotions and behave around others. All of this occurs within social time and space. People age uniquely depending on where, when, and with whom they live, opportunity for social activity, engagement, and leisure, and accessibility to family and community resources and other social provisions.

There are four ways humans are believed to age biologically, psychologically, and socially across the life-span. First, some persons age optimally. Optimal aging involves the capacity to function across many domains physically, mentally, and socially with limited to no interference from age-associated changes. Other persons encounter normative aging, or the ability to function despite the presence of anticipated or expected age-related change of slowing in one’s biological, mental, or social functioning. Yet, humans may also experience secondary aging, or the capacity to adapt to encountering persistent or life-long pathologies impacting physical, mental, or social functioning. Finally, there are many persons who encounter tertiary aging, or a sudden decrease or cessation of physical, mental, or social functioning near the end-of-life.

Lifespan versus Life-Expectancy

By now, you might be asking yourself what is the average or even maximum length of time a human beings could potentially survive under the most optimal or successful aging conditions? Research involving centenarians, persons who live 100-109 years of age, as well as super-centenarians, persons living 110+ years of age, have provided important clues into what types of variables, factors, and other conditions in the lifetime of the human species contribute to life-expectancy and the upper limits of life-span. However, it is important to distinguish between the terms life-span, maximum life-span, and life-expectancy. Life-span is best defined as the total number of years a member of a population or species normatively lives. Maximum life-span is the absolute total or longest number of years any member within a given population or species has ever lived. For instance, the grey wolf can live up to 17 years in captivity, the bald eagle up to 50 years, and the Aldabra tortoise over 150 years. Jonathan, the world’s oldest tortoise, recently celebrated his 190th birthday. To date, the maximum recorded lifespan of a human was set by Jean Calment who died in 1994 at the age of 122 years, 5 months, and 14 days. No other human has lived this exceptionally long. Thus, documented and verified record shows that the limit of human life-span is around 122 years. This upper limit is considered to validate the Zugzwang Hypothesis (Rizvi, 2021). Zugzwang is a German word meaning “compulsion to move,” and is used to describe a situation in the game of chess when a player is disadvantaged because all available moves are poor and will weaken any advantage the player may have against an opponent. Relative to maximum human life-span, the Zungzwan Hypothesis posits that any artificial attempt to manipulate or intervene to achieve a longer lifespan may disadvantage the human species and make further life-extension difficult or impossible. It is assumed that all possible mechanisms of natural selection and life extension has already been exhausted within the human species.

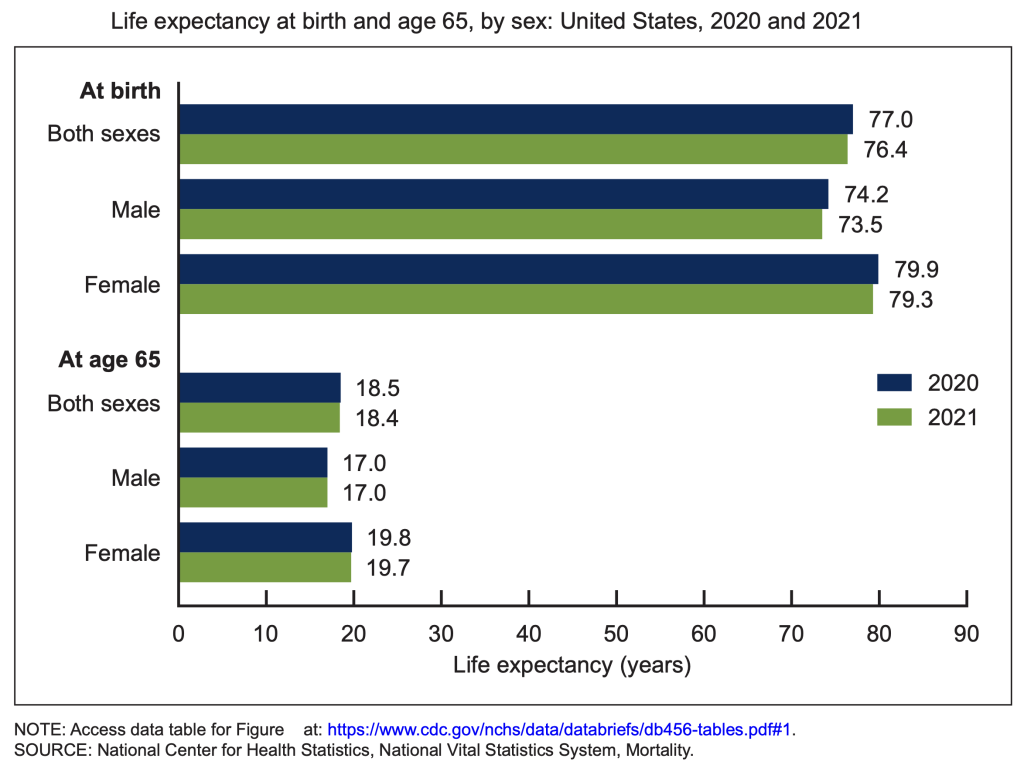

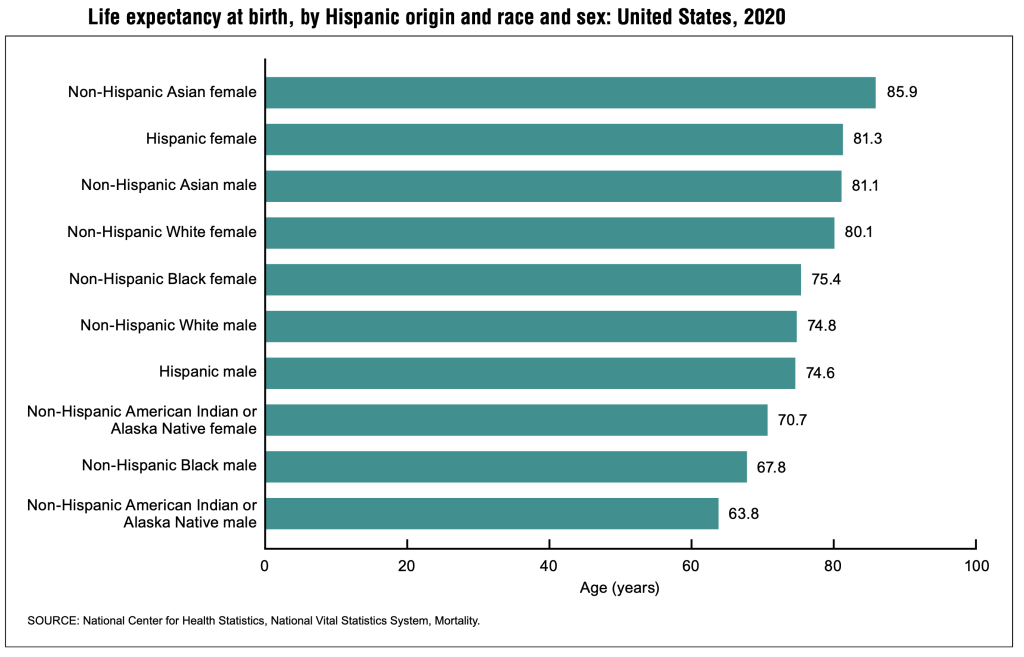

Meanwhile, life-expectancy is a statistical average based on the year of birth that a member in a population or species can expect to live. Given that life-expectancy is a statistical calculation adjusted for current as well as evolving lethal health and behavioral risks, it is important to note that half of all members of a population or species will reach their expected life-expectancy; whereas the other half will die before surviving to their calculated life-expectancy. For instance, life-expectancy at birth in 2021 in the United States was 76.4 years. Life-expectancy reflects a gender-gap in which life expectancy at birth in 2021 is greater among females (79.3 years) than males (73.5 years). It is important to note that COVID-19, among other conditions, negatively impacted and contributed to a decline in life-expectancy rates among persons born between 2020 and 2021. When it comes to race and ethnicity, non-Hispanic Asian females had the greatest life-expectancy at birth in 2020 (85.9 years); where as non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaskan Native males had the lowest life-expectancy rates (63.8 years). Regionally, life-expectancy rates at birth in 2020 were lowest in southern states. For instance, Mississippi is ranked as the lowest overall life-expectancy rate at birth in the United State at 71.9 years. Life-expectancy tends to be greatest in the Western United States. In fact, Hawaii has the highest life-expectancy rate at birth (80.7 years). How life-expectancy will continue to pan out across time during the post-COVID era has yet to be determined, but the impact is likely to continue in the immediate future.

Use Thomas Perl’s Life Expectancy Calculator to see an estimate of your own life expectancy. (Note: This Calculator does require you to enter some personal data. The Calculator is optional and not required for successful understanding of the concepts covered in this chapter.)

Contemporary Worldviews on Life-Expectancy and Human Life-Span

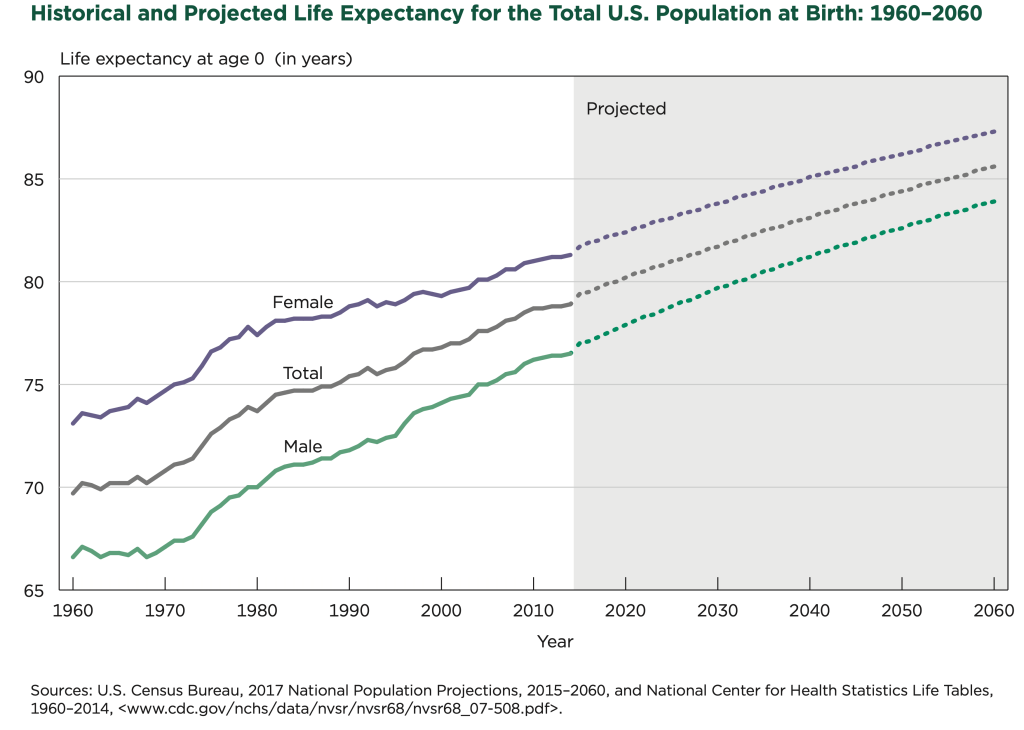

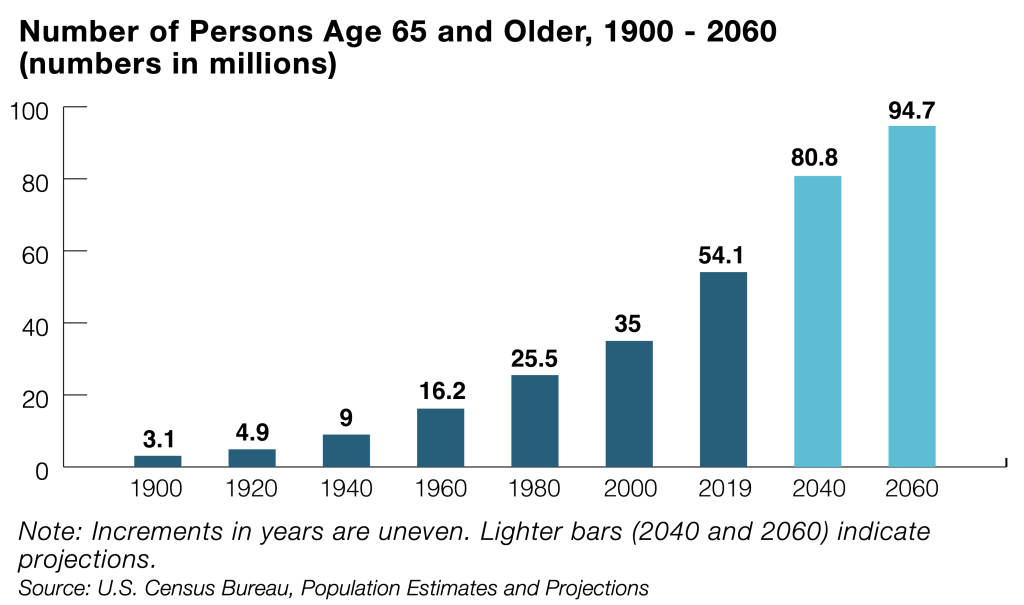

The U.S. is an aging nation and will soon be considered “old.” From 1900 to 2013, life-expectancy at birth rose more 30 years, while the overall death rate fell at a constant rate of around one percent per year.

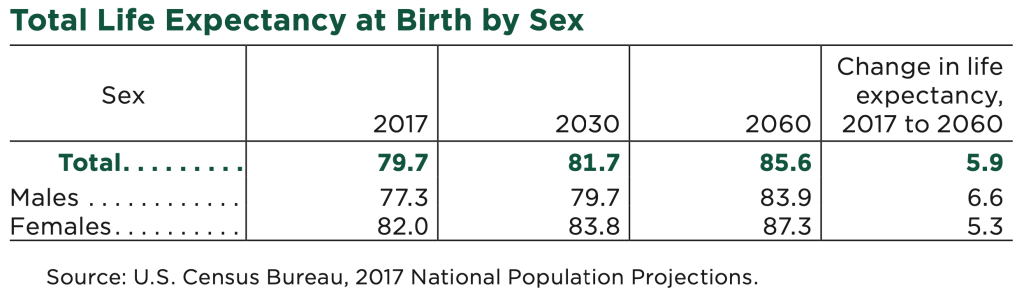

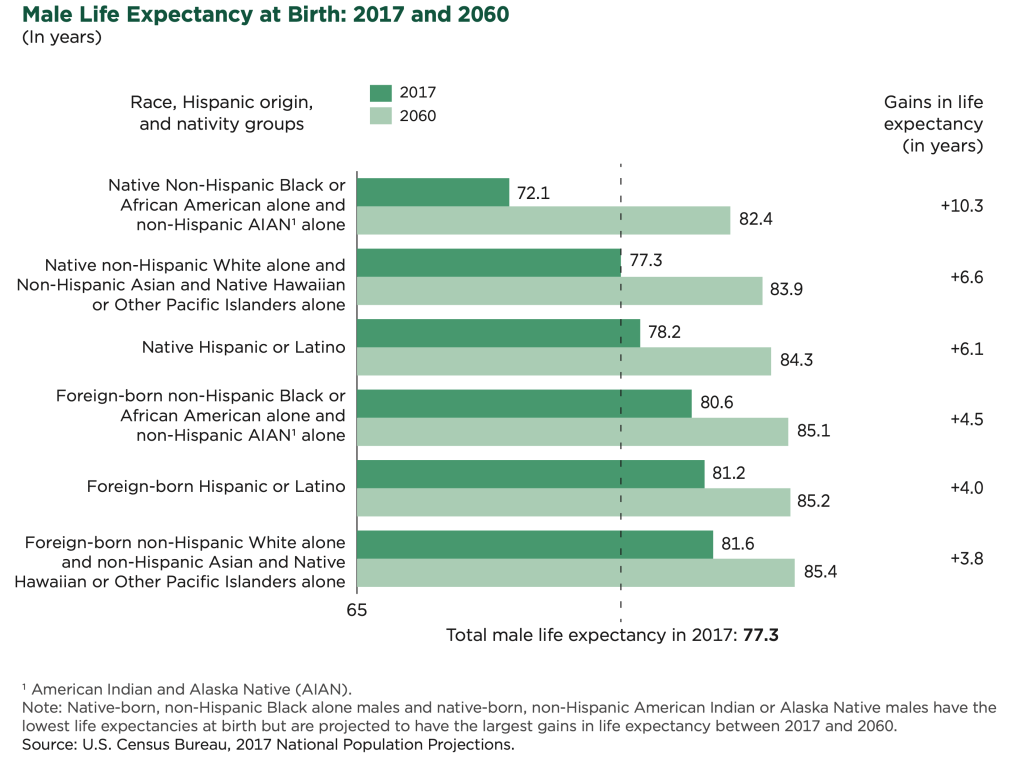

This monumental accomplishment was achieved through various advanced in public sanitation practices, medical advances and breakthroughs leading to immunization for lethal communicable, debilitating, and deadly diseases such as malaria, measles, polio, creation and implementation of dietary and exercise recommendations and programming, and public health legislation and policies. Despite, set-backs in life-expectancy during the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. Census Bureau recently announced anticipation of increased life expectancies among children born in the coming decades. In fact, the U.S. Census Bureau has projected that life-expectancy of babies born in 2060 will have increased by roughly six year from 79.7 years before the COVID-19 pandemic to 85.6 years in 2060. It is predicted that gains in life expectancy will be greatest among men than women. Yet, women will still continue to outlive men. Furthermore, projected life expectancy gains will also increase across all racial and ethnic groups with the greatest gains to be experienced among native-born men who are non-Hispanic Black alone and non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaskan Native alone. (Living Longer: Historical and Projected Life Expectancy in the United States, 1960 to 2060)

Historical and contemporary increases in life-expectancy have contribute to an evolution of three contemporary worldviews regarding human aging and life-expectancy. First, there are many who are “futurists.” Such experts tend to believe that human aging is something that can be cured and eradicated. The futurist perspective acknowledges that science is on the cusp of a major medical or technological discovery and breakthrough involving cellular, molecular, and metabolic processes that control the rate of aging. Such biological controls mean that humans may one day be able to eat, drink, and do to their bodies what they desire; primarily due to the fact that advanced biomedical interventions will be used repair and rejuvenate what once was considered irreparable age-associated deterioration and damage to bodily organs and tissues.

Futurists, such as Aubrey de Grey (2008) and David Sinclair (2019) have boldly predicted and claimed that history will soon witness the first human beings to live 500-1,000 years within this century. A second worldview of aging is the optimist perspective. Optimists propose that the human life-span is not fixed but rather a function of life-expectancy and population size. Optimists, such as James Vaupel and Bernard Jeune (1999), have suggested that a proportional majority of all humans living within industrialized societies today are benefiting from accessibility to biopsychosocial resources and interventions; a necessary condition that helps delay or offset mortality risks and makes survival to 90 to 100 years with or without disease highly probable. A third contemporary view on human aging is the realist perspective. Realists agree that humans have the underlying potential to live beyond the normative limits of life-expectancy, yet the inability to find a real cure and eradicate leading causes of death including heart disease, cancer, or Alzheimer’s represents a limitation. Therefore, realists like Jay Olshansky and Bruce Carnes (2009) have claimed that the status quo of aging and longevity means that human life-expectancy now and into the future will not exceed 85 years. Realists advocate for producing a longevity dividend which involves greater investment in evidence-based research and education, as well as cost-effective initiatives, preventions, and policies that help off-set and delay onset and progression of age-associated disease and disablement while extending the human health-span or the number of quality-of-life-days persons can expect to live until probable time of death absent of chronic, disabling, or lethal conditions. When it comes to human aging what are you: a futurist, optimist, or realist? Perhaps, only time will tell.

Socio-demographic Realities of Aging

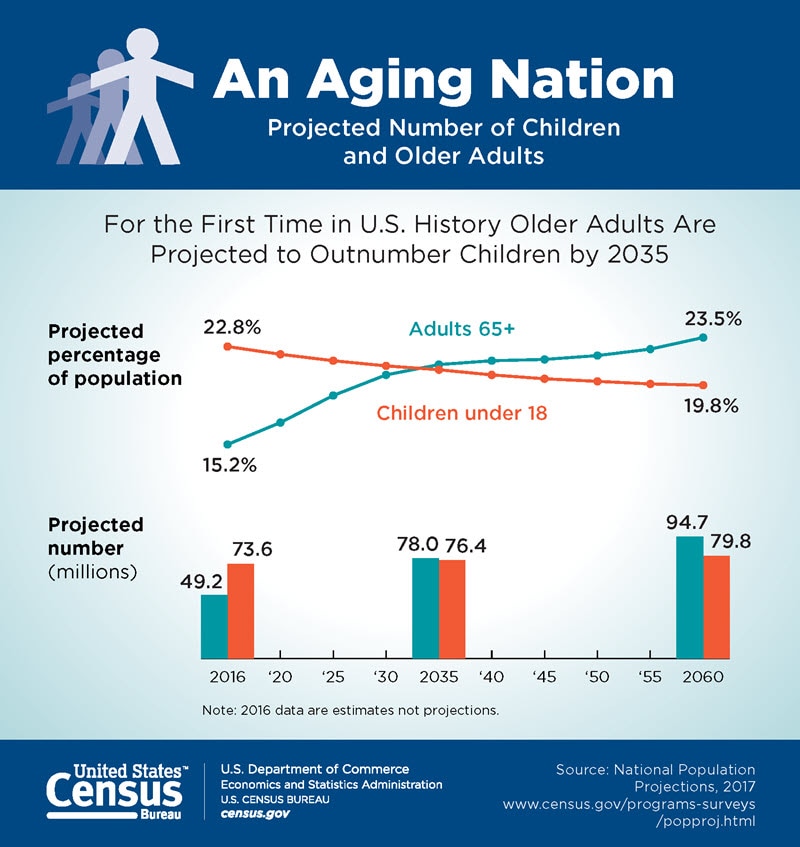

In the early 1990s, Ken Dychtwald and Joe Flower published one of the most provocative and comprehensive overviews on demographic aging in the United States. The title of this book was, Age Wave: The Challenges and Opportunities of an Aging America. Borrowing from Paul Revere’s famous midnight ride during the revolutionary war, the author’s prospective message was quit simple: “The Boomers are coming.” At the time, the Baby Boom Generation or persons born between 1946 to 1964, were roughly 26 to 24 years of age and numbered and estimated 80 million. Nearly three decades later, the Baby Boomers are still here, but this time they are demographically and significantly contributing to the aging of the United States’ populace. Over the next decade, the United States will reach a major milestone in human aging. For the first time in U. S. history, older adults will outnumber children. In fact, the U.S. Census has predicted that persons aged 65 and older are expected to number approximately 77 million, whereas children under age 18 are projected to number 76.7 million.

Age Demographics

There are several factors contributing to this forthcoming demographic shift. However, three primary reasons for this demographic shift include that fact that:

- First and foremost, all members of the Baby Boom Generation (persons born between 1946-1964) will have officially reached age 65 before 2030.

- Fertility and birth rates have continued to decline since 2016, including a significant one-year drop in births during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021.

- Notable decrease in life-expectancy rates birth cohorts beginning in 2015 largely due to increased population mortality due unintentional injuries, drug overdoses, homicides, and suicides. It is important to note that that aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic will likely have no impact on this shifting future age demographics in the United States. The Centers of Disease Control (CDC, 2022) has reported that 81% of all reported COVID-19 deaths at the height of the pandemic in 2020 occurred among persons aged 65 and older, this death rate was 2.8 times great for older adults aged 85 and older and well-over half or 67.8% all COVID-19 deaths among those aged 65 and older occurred within nursing homes or long-term care facilities. Thus, COVID-19 demographically impacted the very old and medically frail in society more pervasively than the young and old alike, who were more abled-bodied and physically robust enough to overcome the threat of illness.

Social demographers and gerontologists commonly classify and divide older adults into three age groups: young-old (persons aged 65-74); old (persons aged 75-84); and the old-old (persons aged 85+). In the United States, an estimated 55.7 million persons are aged 65+ and account for 17% of the population. This proportion is expected to increase to 22% by 2040. Since 1900, the older adult population itself has become increasingly older across all age categories in the United States: 65-74 (32.5 million; 14 times more than 1900); 75-84 (16.5 million; 21 times more than 1900) and; 85+ (6.7 million; 54 times more than in 1900). The 85+ population represents one of the fastest growing age demographics in the United States and is expected to double from 6.7 million persons in 2020 to 14.4 million. This represents a 117% increase. Just under 105,000 of these persons are designated as centenarians, or persons age 100 or older, a number which has tripled since 1980 and is expected to also increase in the coming years. The dramatic increase in the number of older adults living in the due in large part to the aging of baby boomers. Over half of the baby boom generation is now 65 and older. From 2010 to 2020, the number of older adults increased from 40.5 million to 55.7 million – a 38% increase. By 2040, it is projected that there will be 80.8 million older adults, aged 65 and older. This is more than twice the number of person 65 years of age and older who were alive at the turn of the century in 2000. Approximately 1 in 10 people over aged 65 live in poverty.

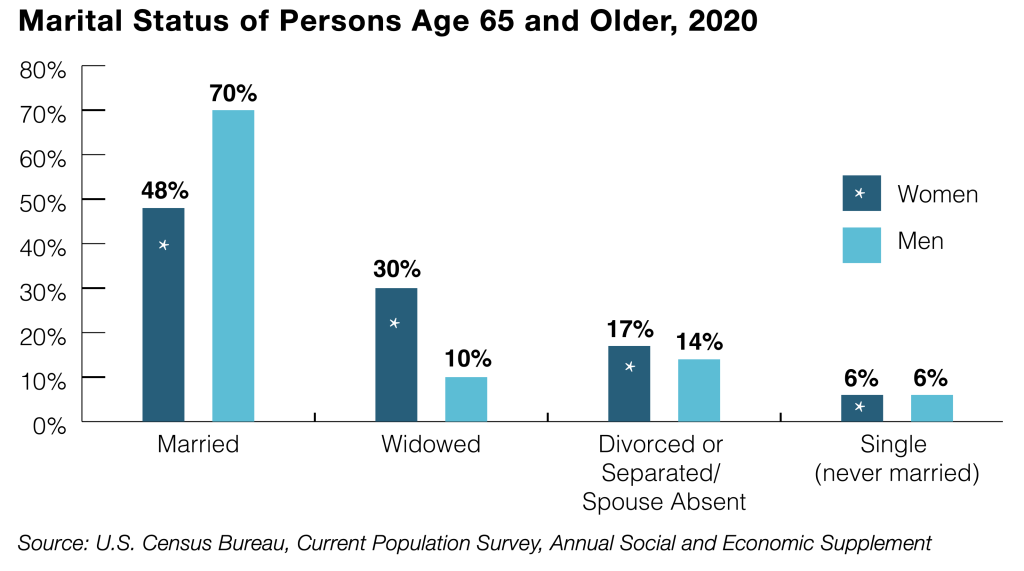

Sex/Gender Demographics

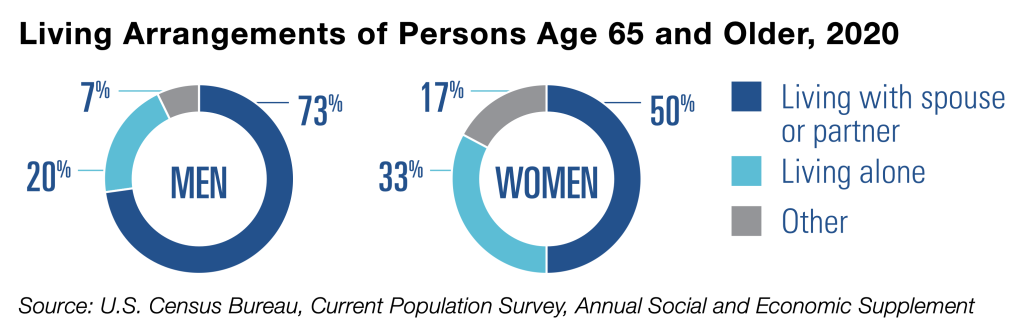

Older women, age 65 and older, significantly outnumber older men. In 2020, there were 30.8 million older women compared to 24.8 million men over the age of 65. This translates into 124 women for every 100 men. Among persons 85 years of age and older, this ratio increases from 176 women for every 100 men. However, a much larger proportion of older men (69%) are married compared to women (47%). Approximately one-third of all older women over age 65 are widowed and age alone. There are nearly three times the number of widows compared to widowers. Relative to economic disparity, older women maintain a higher poverty rate (10.1%) compared to older men (7.6%). Less than 1% of older Americans identify themselves as LBGTQ. However, this proportion is expected to rise in the future.

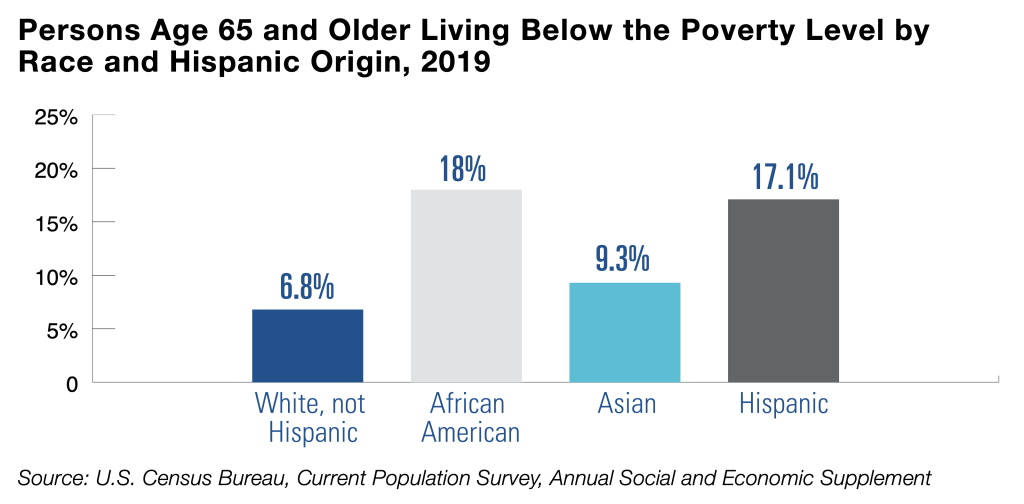

Racial/Ethnic Demographics

The older adult population is increasingly becoming more racially and ethnically diverse. Nearly 1 in 4 or 25% of all older adults are currently members of a racial or ethnic minority population. Between 2020 and 2040, the White (non-Hispanic) population over age 65 is expected to increase by 26% compared to 105% for older racial and ethnic minority population. In fact, Hispanic non-White older adults age 65 and older are projected to have the largest proportion increase at 158%, followed by Asian-Americans (93%), Black/African-Americans (73%), and American Indian/Alaskan Native (58%). Across racial/ethnic groups, a greater proportion of African-American/Black older Americans (17.2%) and Non-White Hispanics (16.6%) tend live below the poverty level. The highest poverty rates are experienced among older non-White Hispanic women who live alone (35.6%).

Living Arrangements

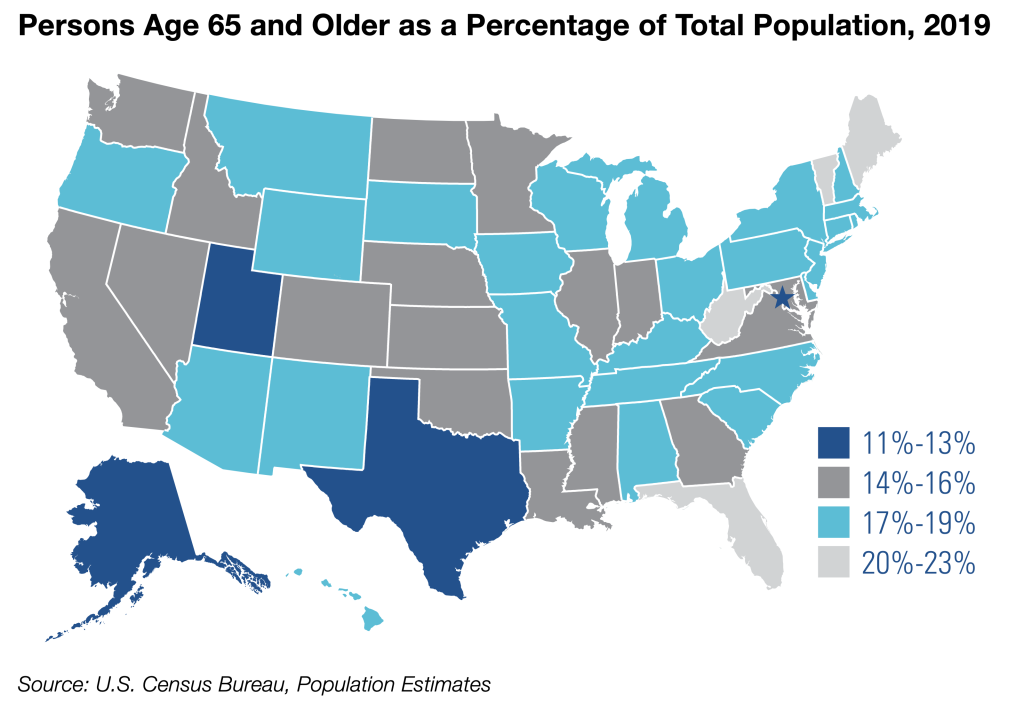

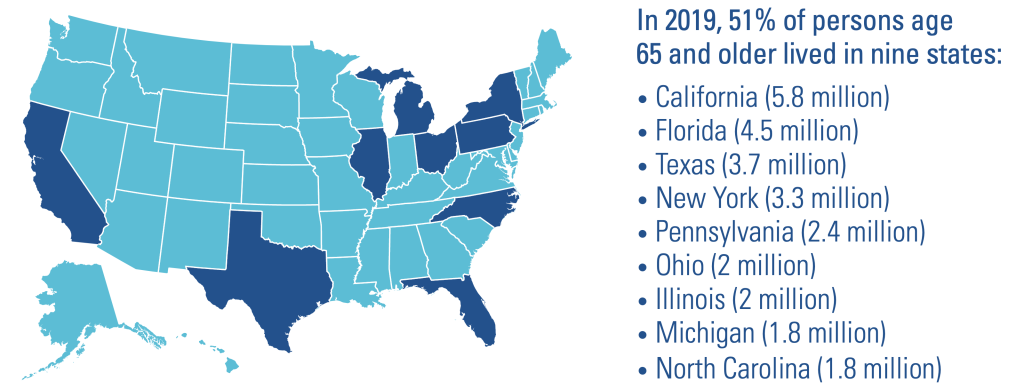

Just over half of 51% of Americans age 65 and older lived in nine states. In fact, the four states with the highest proportion of older adults, aged 65 and older, include Maine (22%), Florida (21%), West Virginia (21%), and Vermont (21%).

Well-over half (60%) of all older adults live with their spouse or partner in private community-dwellings. Approximately 27% of these older adults reside alone at-home. This proportion increases with age for both men and women. For instance, an estimated 43% of women aged 75 and older live alone. It is important to note that a relatively small proportion of older adult live in nursing homes. However, the percentage of those who do reside in nursing homes is increases with age and ranges from 1% for persons 65-74, 2% for persons 75-84 years of age, and 8% for persons age 85 and older.

It is important to note that older adult typically age-in-place and do not change living arrangements as often as younger age groups. Over half of all older adults who do move (55%) usually relocate within the same county, another 21% relocate within the same state, and another 24% either move out-of-state or abroad.

Joe Rogan Podcast Series with Aubrey de Grey (Futurist Viewpoint)

Joe Rogan Podcast with David Sinclair (Futurist Viewpoint)

James Vaupel (Optimist Viewpoint)

Jay Olshansky (Realist Viewpoint)

Socioeconomic Demographics

The evidence is clear. Aging is a demographic reality poised to impact persons of regardless of age, sex/gender, racial or ethnic background, or place. In the coming decades, there will be ample opportunity to educate and provide aging individuals, families, and care providers with advice, counsel, and strategies for aging successfully. Based on projected demographic evidence, will age demographics be a little too demanding to handle and efforts to promote successful aging a little too late? This is a question which is hoped can be answered in the coming sections and chapters of this book.

Key Takeaways

The most important points from Chapter 1: Introduction include…

- Aging affects everyone. It is a continuum of short- and long-term developmental change and stability, and among populations of individuals.

- There are many forms of aging, such as Biological Age, Psychological Age, and Social Age.

- People age uniquely depending on where, when, and with whom they live, opportunity for social activity, engagement, and leisure, and accessibility to family and community resources and other social provisions.

- The United States will soon have more older adults than children–a phenomenon that has never occurred in this country before. This will dramatically impact many aspects of our society including healthcare, living arrangements, poverty, and more.

References

Lally, M., & Valentine-French, S. (2019). Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective – Second Edition

Rizvi, S. I. (2021). The zugzwang hypothesis: Why human lifespan cannot be increased. Gerontology, 67(6), 705–707. https://doi.org/10.1159/000514861

Rowe, J. W., & Kahn, R. L. (1997). Successful aging. The Gerontologist, 37(4), 433–440. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/37.4.433

Sinclair, D. A., & LaPlante, M. D. (2019). Lifespan: The revolutionary science of why we age–and why we don’t have to(First Atria Books hardcover edition). Atria Books.

All original material in this chapter by Alex Bishop is licensed CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, as indicated in the chapter licensing data. Links retain their original copyright, and unless specifically licensed otherwise, comments and work shared by those interacting with the material retain full copyright.

The process by which humans change, grow, and development across the life-span