21 Development of a Web-Based e-Extension Mediated Communication Instrument for Farmer Education Amidst Covid-19 Pandemic in Delta State Nigeria

Emmanuel U. Tibi, (Ph.D); Pauline I. Tibi, (PhD); Benjamin B. Adeyemi (PhD); and Nkechi D. Isitor

Abstract

Agricultural extension stands in the gap between government agricultural policies, programmes and projects and the farmers who need ideas, advice and information to effectively carry on agricultural activities across the value chains. E-extension is the deployment of information and communication technology (ICT) tools used in carrying out extension service delivery. Previously in Delta State, extension use to comprise mainly of face-to-face contact between extension agents/advisors and farmers, but the emergence of COVID-]9 pandemic made this practice unsafe, occasioning lockdown and social distancing. E-extension was adopted by Delta Agricultural and Rural Development Authority (DARDA previously ADP) by using electronic and internet tools, such as radio and television broadcasts, social media applications and web-based data gathering tools. (www.darda.org.ng; www.darda.org.ng/portal/login.asyx). These required the deployment of devices such as computers, mobile phones, internet, video cameras, personal digital assistants (PDA‘S) etc. While e-extension has the potentials of ensuring agricultural information gathering and dissemination to and from farmers, it was confronted by several challenges such as poor receptivity of radio and television broadcasts in rural areas, poor internet connectivity, lack of mobile phones, ICT illiteracy amongst extension agents and farmers, and poor installed capacity of e-extension devices in the extension zone blocks and cells. Suggestions on enhancing farmer education include training and retraining of extension agents and farmers, improving receptivity of broadcasts, and network connectivity, issuance of mobile devices as loans to agents and farmers and adhering to COVID-19 protocols.

Keywords: e-extension, farmer education, Covid-19 pandemic, radio and television broadcast, social media, web-based, mediated tools.

Introduction

The success of agricultural ventures in any nation is predicated on the commitment shown by the government and the farmers. While government generates policies, programmes and regulations that guide agriculture as a critical sector that enhances the economy of the nation, the farmers (agriculturists) are the persons that carry on farming and associated activities that make it contribute to economic development of that society. In this mileu, agricultural extension stands in the gap between government and the farmers by bringing developments in agricultural policies, programmes and projects to the people (farmers) while transmitting the challenges of farmers to agencies of government for resolution and communicating same to the farmers to promote agriculture. In the words of Goldberg (2009) education must lead to empowerment enabling individuals to be capable of making decisions, and meeting the changing needs of people and the society. This view extends to farmer education which is needed for enhanced agricultural productivity.

In Delta State, extension service delivery is the responsibility of the Agricultural Development Programme (ADP). It is the extension arm of the ministry of Agriculture and National Resources (MANR). It was initiated in the State from 1999 and till date ADP (Now Delta Agricultural & Rural Development Authority, DARDA) has implemented programmes such as extension services, women in agriculture (WIA), seed multiplication, crop adaptive research, agro forestry, land management, livestock production, fisheries production, farm road rehabilitation, rural water schemes and Fadama farming, (MANR, 2019). ADP also collaborates with the Federal Government and other international agencies to implement intervention programmes and projects such as root and tuber expansion programme (RTEP), National Programme on Food Security (NPFS). Livelihood Improvement for Family Enterprises in the Niger Delta (LIFE-ND). All these programmes and projects are targeted interventions directed towards rural, small holder farmers, aimed at making their agricultural enterprises profitable and sustainable. Usually, they are managed by the extension arm of the Ministry of Agriculture and Natural Resources, whose agents are competent, trained and retrained periodically to transfer information, technologies and techniques to the farmers for success in farming.

In this extension service delivery, it involves physical contacts and interactions among extension advisors, farmers, researchers, and programme donors and/or other government officials. With the advent of COVID-19 pandemic and the attendant restrictions on person-to-person contact that it threw up across the world, it became really challenging for extension agents/advisors to effectively participate in training programmes and information dissemination to farmers or retrieval of information on farming challenges from farmers, for onward transmission to researchers, input providers customers, markets, distribution outlets etc. Tibi and Ugboh (2007) revealed that ICT is a veritable tool and a requirement for agricultural and rural transformation in Delta State and Nigeria, though it is not widely accessed yet by farmers in rural communities.

The availability of digital technology was perceived as a possible route through which the extension service activities would be conducted while sticking to the protocols enunciated by authorities as ways and means of curbing the spread of COVID-19 pandemic among persons involved in agriculture, especially between extension agents and farmers who need continuous farmer education to remain active, successful and progressive in sustainable agriculture. The utilization of ICT in facilitating knowledge acquisition and dissemination within and between various disciplines had been such that human input is reduced to the barest minimum with supersonic speed, (Ejiofor, 2009). Here lies the advantage of using ICT under the coronavirus challenge imposed on farming.

Statement of the Problem

In the face of the challenges posed by COVID-19 pandemic, especially in hampering the activities of extension personnel to deliver on their farmer education mandate due to restrictions on physical contact between critical stakeholders in agriculture, it became necessary to find innovative ways of delivering on extension services. Salami (2015) stated that education for the 21st Century is that which prepares individuals to survive today’s world of relentless advancement towards uncertain future scenarios. Atajeromavwo et al (2007) studied the problems associated with classification, storage and retrieval of information on soil data, and recommended the use of algorithms for generating various soil classifications, storage and retrieval techniques on soil data and other agricultural mass data. As a way of confronting the problems facing farmer education in Nigeria, occasioned by the COVID-19 scourge, the need to innovate extension delivery in Delta State became critical. Thus, e-extension had to be considered as a way of surmounting this challenge. According to The Victoria State Government (2013), innovation is all about looking beyond what we currently do well, identifying the great ideas of tomorrow and putting them into practice. It is therefore critically important that when changes occur in our environment, the needs of learners change alongside, new data become available and so innovative responses need to be provided to ensure sustainability of life and livelihood. This innovation came by way of introduction of information and communication technology (ICT) into extension delivery, known as e-extension.

How E-Extension Works in Agriculture.

E-extension is the deployment of ICT tools in carrying out extension service delivery to farmers such as use of zoom, Whatsapp message, Whatsapp voice as well as video communications. It also involves the creation of data-base that would enable interactions between stakeholders in the agricultural value chain. According to Akudolu (2002), ICT consists of all kinds of electronic systems that are used for broadcasting, telecommunications and all forms of computer-mediated communications. ICT is simply digital convergence which is facilitated by using digital gadgets such as computers, internet, pager, personal digital assistants (PDAs), radio television communication satellite, digital video camera, fax machine, mobile TV, blackberry, ipads and social media like Twitter, Instant Messenger, Myspace, Facebook, Flicker, 2go, Chatting, Skype, Podcasting, Blogging, Voice over internet protocol (VOIP), Whatsapp etc (Akpan, Ebieme and Ekaenang, 2014).

The purpose of this study was to examine how to use ICT in carrying out extension service delivery to farmers in Delta State in the form of e-extension, that is intended to bridge the gap inadvertently created between extension service providers and farmers by the COVID-19 pandemic whose spread is fueled by physical contact and proximity amongst persons. E-extension, also known as cyber-extension in agricultural practice means the use of information and communications technology in the dissemination of agricultural information concerning technologies, inputs, outputs challenges, processes etc that enhance agriculture. It involves the use of online networks and multimedia in transmitting information between extension practitioners and farmers virtually. Azonuche (2015) stated that ICT facilitates teaching and learning processes since individuals can access information from any part of the world without changing location. This is at the core of extension in agriculture because information on new developments in agriculture can be effectively exchanged between stakeholders including extension agents, researchers, farmers, processors, marketers and even consumers, across the whole agricultural value chain, without person-to-person contacts.

The general objective of using ICT as a means of deploying e-extension was to ensure that farmers in Delta State remained in food and other agricultural production even as COVID-19 continued to ravage the world, leading to partial to total lockdown, to stave off its devastating spread, which occurs with human contacts. Specifically the objectives of e-extension include the following:

- to transfer competencies of agriculture (knowledge, attitudes and skills/practices) from extension practitioners an experts to farmers by using web-based technologies

- to effectively collect agricultural data and information from farmers by using mobile applications, in solving farmers’ problems

- to enable extension advisors and farmers take appropriate and precise decisions on agricultural issues.

- to build an efficient and effective database of farmers, to guide government, intervention agencies and community development partners in taking decisions through data that are verifiable.

- to improve on the marketing, pricing, distribution, processing and consumption/use of agricultural inputs and outputs.

- to support the processes of environmental protection, impact assessment and sustainability in agricultural value chains.

Ordinarily, the specific objectives stated above would have been realized mostly through physical contacts, amongst stakeholders in agriculture such as the extension service personnel, the farmers, input suppliers, researchers, teachers of agriculture at the various educational levels etc. These contacts would include training sessions, visits to farms, several meetings as listed below:

- Research Extension Farmer Input Linkage System (REFILS) held annually and at zonal levels by researchers from Nigerian Institute for Oil Palm Research (NIFOR) for the South-South Zone especially for On-farm Adaptive Research (OFAR)

- Steering Committee Meeting of REFILS which rotates from state to state in the South-South zone on a quarterly basis (4 times a year)

- Monthly technology review meeting (MTRM) where farmers submit their farm challenges to researchers for resolution.

- Fort-nightly meetings (FNT) between extension advisors and farmers at the state zonal levels in Agbor, Efurun and Warri.

- Block Level Meeting (BLM) which holds at block (i.e Local government levels) between Block Extension Supervisors and Extension Advisors.

As stated earlier the services provided during these meetings and training sessions consist of the following:

- Agricultural extension services delivery

- Research extension services delivery

- Research extension farmer input linkage services (REFILS)

- Monitoring and evaluation of projects

- Facilitating the provision of improved seeds, seedlings, fish fingerlings, chicks, piglets/weaners etc.

- Farmers education and induction services and

- Advice to farmers on credit facilities (DARDA Service Charter, 2019). All these services were adversely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and this necessitated finding other ways of ADP (DARDA) continuing to interface with farmers and other stakeholders through the deployment of digital technology in form of ICTs.

Use of ICT in Disseminating Extension Information

Having recognized that extension agents/advisors, farmers and other stakeholders may not have the capacity to use sophisticated applications in information gathering or dissemination, under the COVID-19 pandemic situation it became necessary to look at basic electronic tools for e-extension. The identified ones included the following:

- Radio and television broadcasts

- Social media applications

- Web-based data gathering tools

Communication, which is the sharing of ideas and information forms a large part of the extension agent’s job, because in the course of passing ideas, advice and information, farmers decisions are influenced (www.fao.org). As noted further by FAO, (retrieved), the major strength of extension services are the extension workers who personally work through various methods to transfer the technologies to farmers and get them adopted for increased production using the complementary and supplementary tools for extension systems such as radio, television, mobile phones, internet, results and methods demonstrations.

a) Radio and Television Broadcasts in E-extension: As a way of continuing information dissemination to farmers while trapped at home or in rural farms due to the COVID-19 challenge, extension agents resorted to the development and deployment of radio and television jingles, advertisements, audio and video marketing, pricing, technological and agro-chemical broadcasts to farmers in rural communities. Wahab (2015) stated that as opposed to traditional agricultural extension, radio and television stations have a great potential of being able to reach more people at a given time, because broadcasting is made possible through satellites and antennas. In this context, radio or television channels are tuned to, at specified times, dates and days when the agricultural messages are aired in order to benefit from the knowledge, attitudes and skills of agriculture without meeting face-to-face with the agents. Since such messages are planned, produced and recorded, chances are that they are hardly subjected to distortions, as would happen if they were being passed from person-to-person. Besides, repetition of such messages on radio and television guarantees that farmers have many opportunities to access the undiluted information and effectively put them to use. However, as noted by Mubofu & Elia, (2017) despite the great potential which radio and TV broadcast have for knowledge dissemination and accessibility to formers, studies have shown that in Tanzania that the level of usage of these media facilitates for farmer education is still very low on the other hand, Tiamuyi et al (2011) reported that the more farmers own ICT tools, the higher the frequency of using such tools for agricultural purpose.

b) Social Media Applications in E-extension: Social media applications have been introduced into agricultural extension delivery, especially since it became unsafe to have physical contacts amongst stakeholders in carious agricultural activities due to coronavirus pandemic This has become a veritable tool to use in mitigating the challenges posed by the traditional agricultural extension delivery of face-to-face contact between stakeholders. Social media have been described as web based tools of electronic communication that allow users to personally and informally interact, create, share, retrieve and exchange information and ideas in any form that can be discussed, archived and used by anyone in the virtual communities and networks (Suchiradpta and Saravanan 2016). Several electronic tools that support the delivery of information between extension agents and farmers like voice, image, motion, instant messages and application such as Whatsapp, text messages, myspace, etc Of all these social media applications, the easily available ones used in extension are short message service (sms), whatsapp message, whatsapp voice message, zoom (especially for trainings and retrainings), facebook, twitter and video message. Information are exchanged between extension agents and farmers using ordinary, android or i-phones, as well as tablets, i-pads, computer etc.

c) Web-based Data Gathering Tools: Communication between extension agents and farmers would not be possible if there was no point of contact between them. Since COVID-19 impeded person-to-person interaction as found in traditional extension delivery, it became expedient that data on farmers had to be gathered online. This led to the development of the world-wide web data gathering tools. The use of social media applications is also dependent on concrete data of farmers using phones, email, facebook, messaging platforms which need to be linked to the database of the extension agency (DARDA, 2020).

Tim Berners-Lee, A British scientist invented the world wide web (www) in 1989, while working at the European Council for Nuclear Research (CERN). www was originally designed to meet the demand for automated information sharing between scientists in universities and institutes around the world. It was meant to merge the evolving technologies of computers, data networks and hypertext into a powerful and easy-to-use global information system, based on texts, clear picture displays, videos and audio. The tools describe the design, development and implementation of web based agricultural extension in Delta State, also known as e-farming information from DARDA to farmers researchers, investors, importers, exporters, manufacturers, marketers, distributors etc. Introducing farming information system on the www allows potential users to query and obtain desired information, since the data in this system are stored in a central database which is maintained by experts. The product output is an operational mobile application known as DARDA Farmers Data Collection Tool Kit which has a total of twelve (123) thematic areas of agriculture as follows:

- Land and related agricultural issues e.g. tenure etc.

- Agricultural practices

- Crops

- Livestock

- Services for agriculture

- Demographic and social characteristics

- Irrigation for off-season agriculture

- Work on the Holdings

- Gender issues/women in agriculture

- Aquaculture

- Artisanal Fishing/fisheries

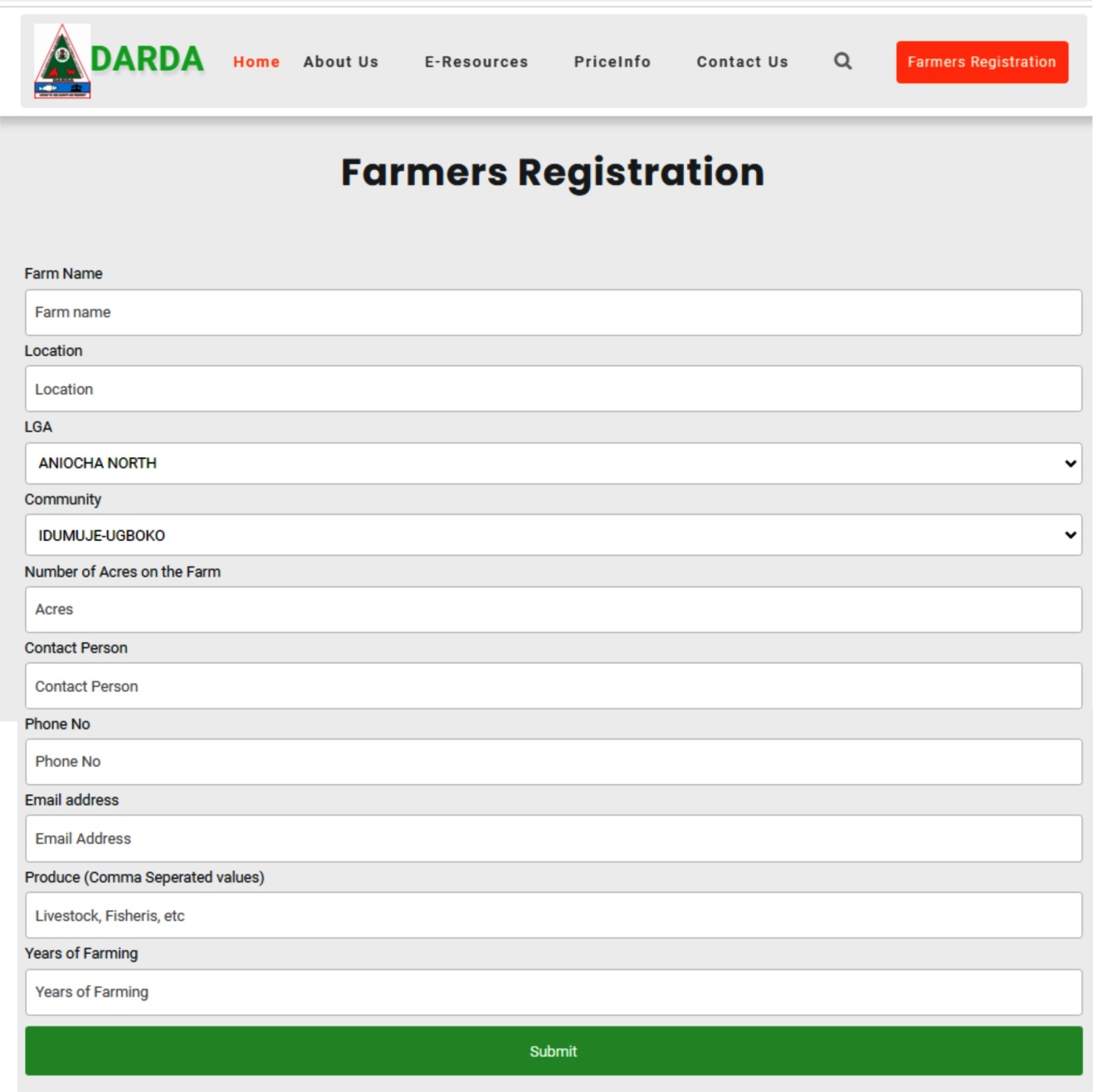

In order to achieve this, an operational interactive and easily navigable e-extension mediated communication (e-EMC) platform was developed. This was backed by an operational Uniform Result Location (URL) of backend application purely for DARDA staff i.e. www.darda.org.ng. Equally, a frontend output view for all i.e. DARDA staff, farmers, researchers, investors, marketers and other stakeholders etc as well as for farmer registration i.e. www.darda.org.ng/portal/logion.aspx.

The choice of the software used to design the forms and the database was based on simplicity, robustness, and ease of coding. To successfully implement this information system the following files were paramount: Login.php, signup.php, profile.php, welcome.php and style.css.

Creating a user based signup site seemed a daunting task in the past but today we can import/acquire the data of already existing users on the DARDA database. The whole process consists of two parts. User registration or (sign-up) and user authentication (sign-in). The form below shows this:

Challenges in Extension Development

Several challenging issues emerged while developing and implementing e-extension during the COVID-19 outbreak. These included many of the underlisted but not exhaustive encounters:

- Poor receptivity of radio and television broadcasts in rural farming communities due to limited ranges of the radio and telecast antennas and masts as well as the qualities of radio and television receivers owned by the farmers.

- Coupled with above, was the issue of poor internet connectivity and low installed capacity of ICT tools in rural areas. Situations were made worse with non-availability of regular electricity supply in these areas.

- Lack of ICT enabled tools such as mobile phones, tablets, ipads, laptops, computers etc, in addition to training deficiency on usage amongst agents and farmers

- High level of ICT illiteracy amongst extension agents and farmers, resulting in poor capacity to develop skill-based training materials for farmers

- Resistance to change amongst extension agents and farmers who had been used to person-to-person contacts of traditional extension delivery.

- Restrictions that were placed on stakeholders such that the bare essentials needed to implement e-extension were not even available, due to the intensity of the coronavirus spread, thus limiting the level of success of the programme.

Suggestions of Implementing E-Extension

As ways of improving the effectiveness of e-extension delivery during the coronavirus scourge, the following suggestions were made:

- There should be virtual/digital training and retraining of extension agents, farmers and other stakeholders in the agricultural sector on the use of ICT.

- There should be enhanced installed capacity of electronic broadcast facilities to improve receptivity of radio and television extension programmes on farming communities, markets and distribution facilities.

- ICT and internet connectivity should be extended to all the rural and urban communities for stakeholders’ use.

- Mobile devices such as android phones, tablets, I-pads, laptops, desktop computers as well as internet kiosks for community based farmers’ Data Collection tool kits should be provided for trained and periodically retrained farmers to upload and/or download data, while adhering to stipulated COVID-19 protocols.

References

Akpan, G.A. Ebieme E.O. & Ekonang, N.M. (2014) Information and Communication Technology (ICT): A Panacea for Youth Restiveness in Nigeria. Presented at the 21st Annual International Conference of the Nigeria Vocational Association (NVA) February 2014, at University of Uyo, Nigeria.

Akudolu, L.R (2002): Information and Technology Centered Education: A Necessity for National Development and Integration in R.C. Ebenabe and L.R. Akudolu (Eds) Education for National Development and Integration. Awka. Faculty of Education, Nnamdi Azikiwe University.

Atajeromavwo, J.E, Tibi, E.U. and Ugboh O. (2007): The use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in the Conceptualization of Soil Classification Database. International Technology Education and Development Conference (INTED), at Valencia, Spain, March, 2007.

Azonuche, J.E.D (2015); Availability and Utilisation of I.C.T. in Clothing and Textiles Education for Effective Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET) and National Development. Presented at the 23rd Annual International Conference of Nigeria Vocational Association (NVA), 5th – 8th August, 2015 at Yaba College of Technology Lagos.

Delta Agricultural and Rural Development Authority (DARDA) (2020): DARDA Service Charter: The New Face of ADP, 2020 Bulletin.

Ejiofor, T.E (2009): Utilization of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) in Implementing Agricultural Teacher Education in Anambra and Enugu States. Constraints and Enhancement Measures. Nigeria Vocational Journal 14(1) pp. 90-97.

Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO): Retrieved www.fao.org (https://bsmrau.ed.bd>sites,19/05/2021

Golberg, M (2009): Social Consequence: The Ability to Reflect Deeply Held Opinions about Social Justice and Sustainability in A. Stible (ed) The Handbook of Sustainable Literacy: Skills for a Changing World. Devan. Green Books.

Ministry of Agriculture and Natural Resources (MANR) (2019): Hand Book on Delta State Agriculture and Natural Resources, Second Edition, Asaba. December, 2019.

Mubofu, C. and Elia, E. (2017): Disseminating Agricultural Research Information: A Case Study of Farmers in Mlolo, Lupalama and Wenda Villages in Iringa District, Tanzania, University of Dar es Salam Library Journal 12(2) pp 75-96.

Suchiradpta B. and Saravanan, R (2016): Social Media: Shaping the Future of Agricultural Extension and Advisory Services. www.academia.edu (retrieved 19/5/2021).

Tiamuyi, M, Bankole A. and Agbonlahor, R (2011): The Impact of ICT Investment, Ownership and Use in the Cassava Value Chain in South-Western Nigeria. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development 3(3) PP 179-201

Tibi, E.U. and Ugboh O. (2007). The Use of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) in Agricultural and Rural Transformation in Delta State. African Research Review 1(3)pp. 1-7. www.ajel.info/index.php./afrew/article/view/41009.

Victoria State Government (2013): Innovation in Education www.vic.gov.au/research/innovation/. Retrieved on 21/05/2021.

Wahab, A.W.A (2015): Signal Processing of Information for Digital Broadcasting: A Case Study of Nigeria and Kenya. International Conference on Imaging, Signal Processing and Communication, Penang Malaysia. July, 2017.