TEACHER GUIDE

Four Quarters of Choice Reading: A Progression

Sarah J. Donovan

For the past few years, choice reading has been the foundation of my reading pedagogy because choice values students as human beings with a range of interests, experiences, and tastes and because choice shares the responsibility of teaching with all the readers and books in the classroom. I rely on the authors to start conversations about the world with students in the pages of the books they carry.

It is, in fact, true that you (teachers) can teach all of the standards and all of the natural ways real readers read when your students are all reading different books. And it is true that book groups, whole class novels, essays, articles, poetry, and spoken word are also very important in a rich reading life — so, of course, there is more to reading instruction than choice reading. Still, each student will have a reading life to contribute to discussions, and he/she will be the expert on those books and those reading experiences. In other words, if the only texts students read in class are shared texts, then the conversations will be rather narrow and privilege the loudest voices.

All this said, when teachers have from 90 to 180 students reading different books, it can be difficult to track what everyone is reading and even more difficult to assess comprehension, emotional reactions, and the identification and interpretation of author’s choices.

Documenting reading responses — written, verbal (in person/recorded) — is the best way I have found for me to assess students’ reading and for students to self-assess and set goals for their personal reading lives.

I have found that when students notice trends in their reading choices that they will make slight adjustments and be more willing to try new books.

I have also noticed that regular feedback on what students are noticing when they are reading will 1) promote a deeper appreciation for author’s craft and 2) improve meta-cognitive tendencies (or make them more aware or conscious of the many features of a rich reading life).

Reading response feel a lot like reading logs, but there is no parent signature or counting of minutes for a grade. The students must also own their progress. Too much monitoring creates a negative association with reading, so finding a balance of how and when to respond to reading takes constant revision.

I offer here four different ways I have conducted reading responses and supported students in tracking their reading choices. The most important component is the modeling and practice during class time. This is practice. I do not assess the practice. What I do not have here are the portfolios that we do every quarter, which I do assess because the portfolio shows the trends, evidence of comprehension and interpretation, and reading patterns. The portfolio is owned by the students and narrated by them — their voices talking through their reading lives. Only after gathering the data can they see trends and set new goals.

The focus of this section is just to show how I tried to understand each student as a unique reader while teaching and assessing the standards: 1) Cite several pieces of textual evidence to support analysis. 2) Determine a theme and analyze its development. 3) Analyze how particular elements of a story interact (setting shapes character or plot). 4) Determine meanings of words and phrases including figurative and connotative meanings. 5) Read and comprehend a RANGE — widely and deeply — from diverse cultures and different time periods with various text structures.

First quarter reading responses:

Model Noticing Author’s Craft: Model how to create and use the Google Form to track their reading pace, choices in genre and text structure, and response (see video below). Show students how you think about the text and use reasoning and evidence to think through this.

Homework: Over the years, I assigned less and less homework, but we recognize that some schools do require this. Expect two or more additional responses at home for practice. Please avoid reading logs or parent signatures, which create a surveillance tone. Give feedback on one a week in class and adjust the modeling instructions to tweak the quality of reading responses. While students are reading, do NOT read, too. Instead, use this time to check in with students to praise their reading progress or offer suggestions/revisions. See the conferring section here.

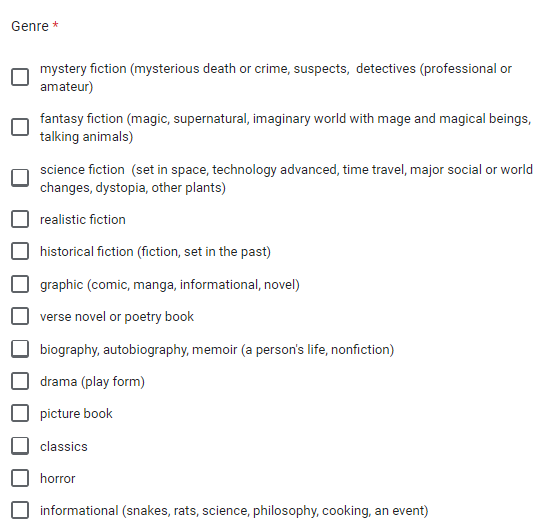

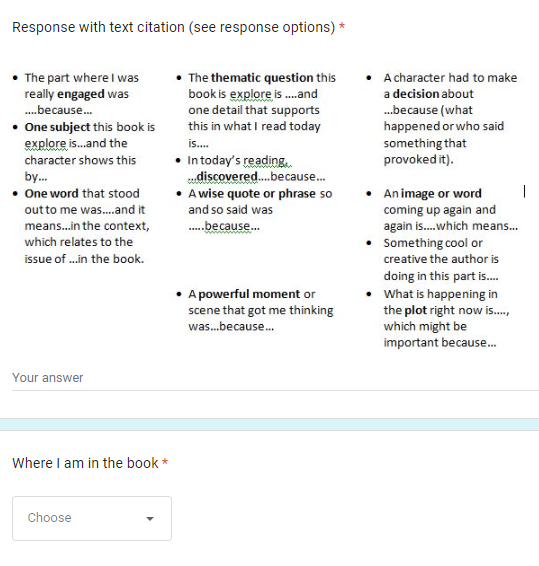

Evidence Form (QR code): Each student should make his/her OWN Google form or survey form so that they are in control and have ownership of their reading life/record. Model how to set this up and use it yourself. Talk about what it is like to document your reading and what feels useful or intrusive. Have students share their form with you and insert a link to their form for you on a class hyperdoc roster. (See below for screenshots; click the link for an example.)

Image 1. Show the range of genre/form options.

Image 2. Students can write their response within the form and select from a range of topics.

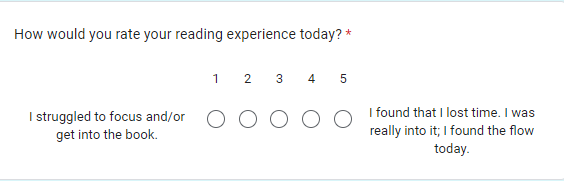

Image 3. A quick rating acknowledges not every reading experience is the same.

Responses practice: We recommend using class time to practice this response form. Model, practice, and assess how students do the following:

Answer the question they’ve selected to ponder about their reading (see response stems below).

Explain the answer (reasoning).

Use for example or because to point to what prompted this thinking.

Include a page number from the text (35) to show in-text citation.

Notice the response stems to help students with independent practice inspired by Notice & Note (Probst & Beers):

What was something the character realized or hasn’t realized yet? Why is that? How will this change things?

What is something (an object, a word, a place, a conflict) that comes up again and again? What might this symbolize (love, hate, grief, the past, forgiveness, friendship)?

What is a time when the character is remembering something in the past or the book flashes back? Why is this important to the character’s personality, concerns, or the book’s conflict?

Think about a setting in your book. If you were in the setting, what are some things you might see?

Describe an important event from your book and tell how it impacted different characters.

Who is your favorite character in your book? Why is this character your favorite- personality, values, choices, interests?

What do you think happened just before your story started? What about that created the opportunity for this story?

If you could give the main character in your book some advice, what would you tell him or her?

Is your book funnier or more serious? Why do you think so? What does the author do to make it so?

What point of view is your book written in? How does it help you understand the thinking of characters?

Do you like the main character of your book? Why or why not?

Think of an important event in your book. How would the story have changed if this event had not happened?

If you could ask the main character of this book three questions, what would you ask?

Think about your book. Then finish this sentence: I wonder….

Think of a new title for your book. Why do you think this is a good title?

In what ways would this book be different if it were set 100 years in the past?

What is the main conflict that the main character in your book must face?

What are some important relationships in your book?

Think about a supporting character in your book. How would the book be different if that character did not exist?

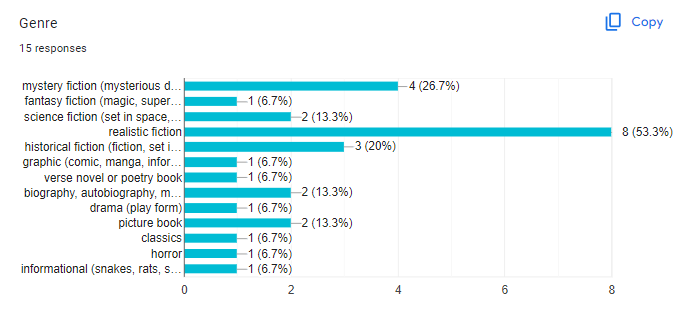

Over time, students will be able to see trends in their reading and then set goals to stretch their reading choices. Or maybe they decide they are ready for new authors or forms. See this snapshot of the form results after 15 entries.

Image 4. Google forms create charts for students to analyze reading patterns and set goals

Second quarter reading responses:

The goal of this next quarter is to explore interpretation and meaning-making. However, you may find that second quarter may need another goal after looking at student forms.

Model making claims about texts: Using CER – claim, evidence, reasoning –model with your student another way of thinking about reading response. See Sarah’s YouTube channel for a video on this.

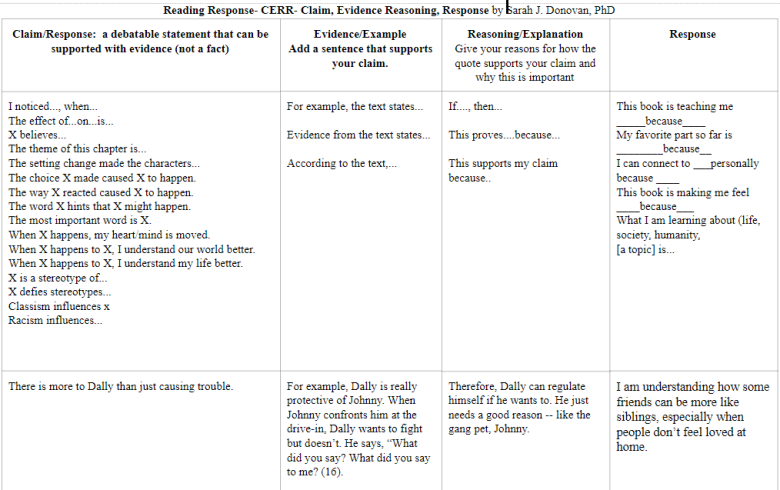

Second quarter is not entirely different from quarter one, but it is a shift in thinking. Instead of talking about “what’s going on in the book,” readers are making claims about the implications of what is going on. This shift builds confidence in readers and opens up nuance as well. Practice CER with a common text — a short story or whole class novel. We read The Outsiders. (See chart below.)

Homework: Keep this the same as in the first quarter or adjust it as needed. I expected three (3) total responses a week on their evidence form, but we used class time for this rather than making it homework. I assessed just one entry. Give students feedback and then adjust your modeling to help students think deeply about the claims they are making. Emphasize that the reasoning should be the longest part of this response because you are more interested in hearing their thinking process. You can teach and model this during conferring time, too.

Evidence Form: Use the same Google form as the first quarter. You will really see a shift in the tone and insight in responses, but you may also see a decline in personal responses, so I added another column R – response to get students to think personally about the claim they made.

Response Format: CER(R) means claim, evidence, reasoning, and response. This is a scaffolded approach to literary analysis writing. The more students see this as a way of engaging with the text in lower stakes, daily reading and writing experiences, the less stressful longer literary analysis papers will be. Of course, this structure supports book group conversations and whole-class Socratic seminar and fishbowl discussions, too. You can create a chart like this for students to paste into their reading notebooks or have a guide for during classroom discussions. We think Just YA is a great resource for teachers to model this process with any of the short texts and then welcome students to select texts to practice analytic writing or discussion. The QR is a video tutorial. Image 5 is an example of a CERR chart.

Image 5. CERR chart with examples from The Outsiders

Third quarter reading responses:

Model how to personalize the responses by giving students a range of methods for sharing their reading experiences. They are likely over the Google form responses, so here are a few ideas:

Vlog (see the section in this book)

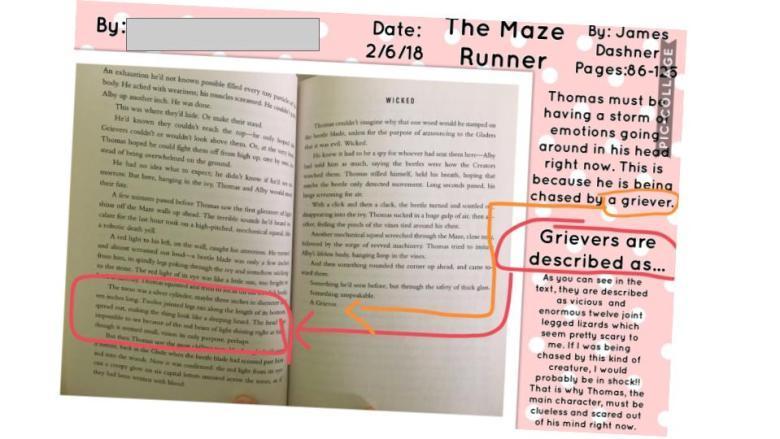

Quotemaker (design quotes from the text followed by explanations)

Booksnaps (picture of the page of a book with a box around a quote and thought bubbles explaining it)

Journal/Diary (doc, slides, or pictures of a notebook to discuss your reading)

Blog (typed directly into the body of the blog)

Homework: Ask for one response during the week and one on the weekend. Again, you may abandon this altogether and use class time for the responses. Definitely, make time for the one during the week so that you can support and offer feedback. Assess the one they do independently and give feedback on that, too.

Evidence of learning: You will no longer use the Google form. Ask students to use the class roster hyperdoc to link to the site or place they will share their medium.

Response format: Students will do claim, evidence (quote) and reasoning, but with greater emphasis on the reasoning and response in their medium.

Date of response

Title of book

Author’s name

Pages read since last response

Claim: character, setting, conflict, author, symbolism, big issue, connections, great words, emotion

Quote: text evidence with page (decide on APA or MLA)

Explanation of what is going on in the book that helps us understand why this claim is important to think about as a person, a reader.

Analysis of what key words mean in the quote denotation and connotation

Analysis of how the words in the quote prove your claim.

State your opinion, connection, emotional response, reaction

Fourth quarter reading responses:

For the final quarter, you may want to ease up on tracking reading, though students are likely keeping track and are amazed by their range of reading now that is visible in Google forms or a notebook list. Use this quarter to reflect on what they’ve read: authors, genres, forms, topics, and make some decisions to stretch or fill-in gaps. Use this time for students to make recommendations to one another. You should do the same.

Students will be very comfortable talking about the author’s craft and genre and form. They will know all the literary elements and how various plots and structures impact their hearts and minds.

This quarter is a great time to review the reading life in the past year, so you can ask students to do a portfolio.

Students will create a comprehensive portfolio documenting their reading journey throughout the school year. This project will culminate in a presentation that reflects on their growth as readers, the impact of the stories they read, and their overall relationship with reading.

Components of the Portfolio:

Reading Forms:

Reading form or chart of all books, stories, genres, and poems read throughout the year.

Include the title, author, genre, and date completed.

Add a brief summary and personal reflection for each entry.

Favorite Reads:

Select a few favorite texts and create a slide or video segment for each, explaining why these were significant.

Discuss what they loved about these texts, any memorable quotes, and how these reads affected them personally.

Stretch Texts:

Highlight texts that challenged their reading habits or expanded their understanding of literature.

Reflect on how these texts stretched their thinking and reading skills.

Learning and Exploration:

Identify stories that taught them something new or prompted further learning.

Include any research or projects that stemmed from these readings.

Poetry Exploration:

Choose favorite poems and explore more works by the same poets.

Reflect on what drew them to these poems and any themes or styles that stood out.

Recommendations:

List books and stories they recommended to others and those recommended to them.

Reflect on the impact of these recommendations and any discussions that ensued.

Reading Reflection Essay:

Write a short essay about their relationship with reading.

Discuss what it means to have a “just reading life,” including access to stories, time to read, space to think about reading, and people to discuss reading with.

Reflect on how these elements have shaped their reading journey over the year.

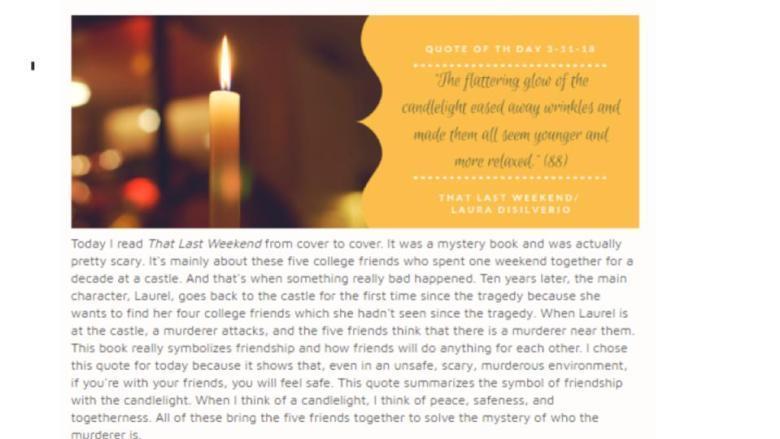

Quotes and Reflections:

Collect favorite quotes from their readings.

Write brief reflections on why these quotes stood out and how they relate to their reading experiences.

Presentation:

Create a slide deck or video summarizing the key elements of their reading portfolio.

Include visual and multimedia elements to enhance their presentation.

Present to the class or a smaller group, sharing insights and highlights from their reading journey.

Final Compilation:

Allocate time towards the end of the year for students to finalize their portfolios.

Provide resources and support for creating the slide deck or video.

Presentation and Celebration:

Organize a presentation day where students showcase their portfolios.

Celebrate their reading achievements with a class discussion or a small event.

Evaluation Criteria:

Completeness: Inclusion of all required components.

Depth of Reflection: Thoughtfulness and depth in personal reflections and essays.

Creativity: Creativity in the presentation format and visual elements.

Engagement: Engagement with the reading materials and the portfolio project.

Presentation Skills: Clarity and effectiveness in the final presentation.

This portfolio project aims to foster a love for reading, encourage critical thinking, and celebrate students’ diverse reading experiences throughout the school year.