4.9 Shinto

Shinto Defined

Shinto , meaning ‘ way of the gods ,’ is the oldest religion in Japan. The faith has neither a founder nor prophets and there is no major text, which outlines its principal beliefs. The resulting flexibility in definition may well be one of the reasons for Shinto’s longevity, and it has, consequently, become so interwoven with Japanese culture in general that it is almost inseparable as an independent body of thinking. Thus, Shinto’s key concepts of purity, harmony, family respect , andsubordination of the individual before the group have become parts of the Japanese character whether the individual claims a religious affiliation or not. (27)

History

Origins

Unlike many other religions, Shinto has no recognized founder. The peoples of ancient Japan had long held animistic beliefs, worshipped divine ancestors and communicated with the spirit world via shamans; some elements of these beliefs were incorporated into the first recognized religion practiced in Japan, Shinto, which began during the period of the Yayoi culture (c. 300 BCE – 300 CE). For example, certain natural phenomena and geographical features were given an attribution of divinity. Most obvious amongst these are the sun goddess Amaterasu and the wind god Susanoo . Rivers and mountains were especially important, none more so than Mt. Fuji , whose name derives from the Ainu name ‘ Fuchi ,’ the god of the volcano.

In Shinto, gods, spirits, supernatural forces and essences are known as kami , and governing nature in all its forms, they are thought to inhabit places of particular natural beauty. In contrast, evil spirits or demons ( oni ) are mostly invisible with some envisioned as giants with horns and three eyes. Their power is usually only temporary, and they do not represent an inherent evil force. Ghosts are known as obake and require certain rituals to send away before they cause harm. Some spirits of dead animals can even possess humans, the worst being the fox, and these individuals must be exorcised by a priest. (27)

Pre-State Shinto

Buddhism arrived in Japan in the 6th century BCE as part of the Sinification process of Japanese culture. Other elements not to be ignored here are the principles of Taoism and Confucianism that travelled across the waters just as Buddhist ideas did, especially the Confucian importance given to purity and harmony. These different belief systems were not necessarily in opposition, and both Buddhism and Shinto found enough mutual space to flourish side by side for many centuries in ancient Japan.

By the end of the Heian period (794-1185 CE), some Shinto kami spirits and Buddhist bodhisattvas were formally combined to create a single deity, thus creating Ryobu Shinto or ‘ Double Shinto .’ As a result, sometimes images of Buddhist figures were incorporated into Shinto shrines and some Shinto shrines were managed by Buddhist monks. Of the two religions, Shinto was more concerned with life and birth, showed a more open attitude to women, and was much closer to the imperial house. The two religions would not be officially separated until the 19th century CE. (27)

By the mid-17th century, Neo-Confucianism was Japan’s dominant legal philosophy and contributed directly to the development of the kokugaku , a school of Japanese philology and philosophy that originated during the Tokugawa period. Kokugaku scholars worked to refocus Japanese scholarship away from the then-dominant study of Chinese, Confucian, and Buddhist texts in favor of research into the early Japanese classics. The Kokugaku School held that the Japanese national character was naturally pure and would reveal its splendor once the foreign (Chinese) influences were removed. The “ Chinese heart ” was different from the “ true heart ” or “ Japanese heart .” This true Japanese spirit needed to be revealed by removing a thousand years of Chinese learning. Kokugaku contributed to the emperor-centered nationalism of modern Japan and the revival of Shinto as a national creed in the 18th and 19th centuries. (28)

State Shinto

Prior to 1868, most Japanese more readily identified with their feudal domain rather than the idea of “Japan” as a whole. But with the introduction of mass education, conscription, industrialization, centralization, and successful foreign wars,Japanese nationalism became a powerful force in society. Mass education and conscription served as a means to indoctrinate the coming generation with “ the idea of Japan ” as a nation instead of a series of Daimyo (domains), supplanting loyalty to feudal domains with loyalty to the state. Industrialization and centralization gave the Japanese a strong sense that their country could rival Western powers technologically and socially. Moreover, successful foreign wars gave the populace a sense of martial pride in their nation.

The rise of Japanese nationalism paralleled the growth of nationalism within the West. Certain conservatives such as Gondō Seikei and Asahi Heigo saw the rapid industrialization of Japan as something that had to be tempered. It seemed, for a time, that Japan was becoming too “Westernized” and that if left unimpeded, something intrinsically Japanese would be lost. During the Meiji period , such nationalists railed against the unequal treaties, but in the years following the First World War, Western criticism of Japanese imperial ambitions and restrictions on Japanese immigration changed the focus of the nationalist movement in Japan. (28)

The Rise of Fascism

In the 1920s and 1930s, the supporters of Japanese statism used the slogan Showa Restoration , which implied that a new resolution was needed to replace the existing political order dominated by corrupt politicians and capitalists, with one which (in their eyes), would fulfill the original goals of the Meiji Restoration of direct Imperial rule via military proxies. Japan had no strong allies and its actions had been internationally condemned, while internally popular nationalism was booming. Local leaders, such as mayors, teachers, and Shinto priests were recruited to indoctrinate the populace. The Japanese government, in fact, nationalized the various Shinto Shrines for the sake of promoting the emperor as a divine being, and a descendent of Amaterasu.

Japan’s expansionist vision grew increasingly bold. Many of Japan’s political elite aspired to have Japan acquire new territory for resource extraction and settlement of surplus population. These ambitions led to the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 . After their victory in the Chinese capital, the Japanese military committed the infamousNanking Massacre . (29)

Japan also attempted to exterminate Korea as a nation. The continuance of Korean culture itself became illegal. Worship at Japanese Shinto shrines was made compulsory. The school curriculum was radically modified to eliminate teaching of the Korean language and history. (30)

The United States opposed Japan’s aggression towards its Asian neighbors responded with increasingly stringent economic sanctions intended to deprive Japan of the resources. Japan reacted by forging an alliance with Germany and Italy in 1940, known as the Tripartite Pact , which worsened its relations with the U.S. In July 1941, the United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands froze all Japanese assets when Japan completed its invasion of French Indochina by occupying the southern half of the country, further increasing tension in the Pacific. War between Japan and the U.S. became an inevitability following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. (29)

Shrine Shinto

The loss of World War II placed Japan in the precarious position of a country occupied by the Allied but primarily American forces, which shaped its post-war reforms. The Emperor was permitted to remain on the throne, but was ordered to renounce his claims to divinity, which had been a pillar of the State Shinto system. Today, the shrines in Japan operate independently from the state, to ensure the separation of religion and state. (31)

Kami

In the Shinto religion kami is an all-embracing term, which signifies gods, spirits, deified mortals, ancestors, natural phenomena, and supernatural powers. All of these kami can influence people’s everyday lives and so they are worshipped, given offerings, solicited for aid and, in some cases, appealed to for their skills in divination. Kami are attracted by purity – both physical and spiritual – and repelled by the lack of it, including disharmony. Kami are particularly associated with nature and may be present at sites, such as mountains, waterfalls, trees, and unusually shaped rocks. For this reason, there are said to be 8 million kami, a number referred to as yaoyorozu-no-kamigami . Many kami are known nationally, but a great many more belong only to small rural communities, and each family has its own ancestral kami.

The reverence for spirits thought to reside in places of great natural beauty, meteorological phenomena, and certain animals goes back to at least the 1st millennium BCE in ancient Japan.

Add to these the group of Shinto gods, heroes, and family ancestors, as well as bodhisattvas assimilated from Buddhism, and one has an almost limitless number of kami.

Common to all kami are their four mitama ( spirits or natures ) one of which may predominate depending on circumstances:

- Aramitama (wild or rough)

- Nigimitama (gentle, life-supporting)

- Kushimatama (wondrous)

- Sakimitama (nurturing)

This division emphasizes that kami can be capable of both good and bad. Despite their great number, kami can be classified into various categories. There are different approaches to categorization, some scholars use the function of the kami, others their nature (water, fire, field, etc.). (32)

Kami are appealed to, nourished, and appeased in order to ensure their influence is, and remains, positive. Offerings of rice wine, food, flowers and prayers can all help achieve this goal. Festivals, rituals, dancing and music do likewise. Shrines from simple affairs to huge sacred complexes are built in their honor. Annually, the image or object ( goshintai ) thought to be the physical manifestation of the kami on earth is transported around the local community to purify it and ensure its future well-being. Finally, those kami thought to be embodied by a great natural feature, Mt. Fuji being the prime example, are visited by worshippers in an act of pilgrimage. (32)

Japanese Creation Story

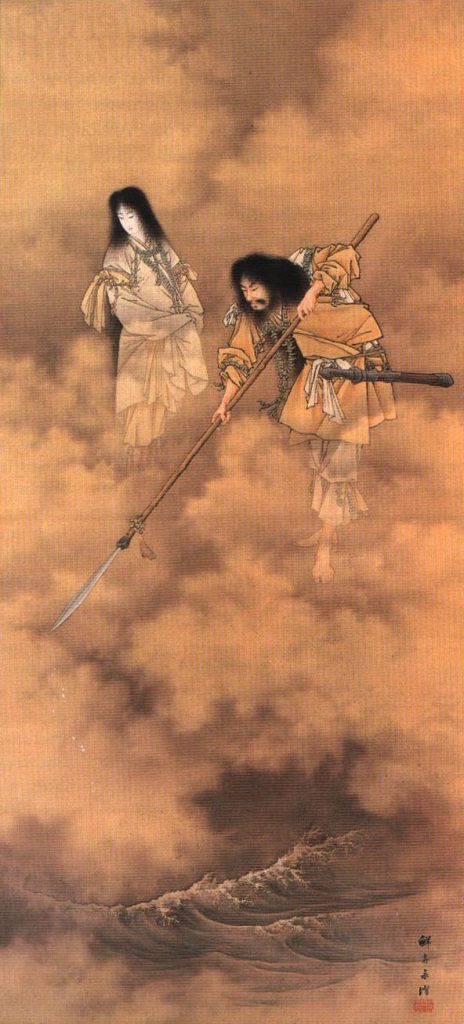

The islands of Japan are the subject of a particularly colorful creation myth. Standing on the bridge or stairway of heaven (known as Ama-no-hashidate , which connected heaven — Ama — to earth ), the two gods Izanami and Izanagi used a jewel encrusted spear to stir the ocean. Withdrawing the spear, salt crystallized into drops on the tip and these fell back into the ocean as islands.

The first island to be created was Onogoro-shima and the gods immediately used the island to build a house and host theirwedding ceremony . The ritual involved circling around a pillar (or in some versions the spear) with the two gods moving in opposite directions. However, during this sacred marriage ritual Izanami , the female deity , wrongly spoke first when they passed each other and as a consequence of this impiety their first child was a miscarriage and born an ugly weakling without bones. This was the god Hiruko (later Ebisu) who would become the patron of fishermen and one of the seven gods of good luck. Hiruko was abandoned by his parents and set in a basket for the sea to take it where it would.

The second child was the island of Awa but Izanami and Izanagi were still not satisfied with their offspring and they asked their parents the seven invisible gods the reason for their misfortune. Revealing that the reason was their incorrect performance of the marriage ritual, the couple repeated the ceremony, this time making sure Izanagi , the male deity , spoke first. (33)

The couple then continued to create more auspicious offspring, including the eight principal islands of Japan — Awaji, Shikoku, Oki, Tsukushi (Kyushu), Iki, Tsu, Sado, and Oyamato.

Also created were a prodigious number of kami. Other notable children were Oho-wata-tsu-mi ( god of the sea ), Kuku-no-shi ( god of the trees ), Oho-yama tsu-mi ( god of the mountains ) and Kagutsuchi ( god of fire ), often referred to in hushed tones as Homusubi during ritual prayers. (33)

Shinto Shrines

Shinto shrines, or jinja , are the sacred locations of one or more kami, and there are some 80,000 in Japan. Certain natural features and mountains may also be considered shrines. Early shrines were merely rock altars on which offerings were presented. Then, buildings were constructed around such altars, often copying the architecture of thatched rice storehouses. From the Nara period in the 8th century CE temple design was influenced by Chinese architecture – upturned gables, and a prodigious use of red paint and decorative elements. Most shrines are built using Hinoki Cypress.

Shrines are easily identified by the presence of a torii or ” sacred gateway .” The simplest are merely two upright posts with two longer crossbars and they symbolically separate the sacred space of the shrine from the external world. These gates are often festooned with gohei , twin paper or metal strips each ripped in four places and symbolizing the kami’s presence.

A shrine is managed by a head priest ( guji ) and priests ( kannushi ), or in the case of smaller shrines, by a member of the shrine elders committee, the sodai. The local community supports the shrine financially. Finally, private households may have an ancestor shrine or kamidana , which contains the names of the family members who have passed away and honors the ancestral kami. (27)

Features of Shrines

The typical Shinto shrine complex or jinja includes some or all of the following common architectural features, depending on its size and importance: (27)

Torii

Torii are sacred gateways, which symbolically separate the sacred space of the shrine from the external world. The simplest and most common are merely two upright posts with two longer crossbars ( kasagi and nuki ), known as the myojin torii , but there are many variations, such as the ornate ryobu torii , which usually stand in water, and miwa torii , which has a triple gate. Torii are usually made of wood but they can also be of stone, steel, copper, or concrete. Many torii are painted red, and they are often festooned with gohei , twin paper, cloth or metal strips each ripped in four places symbolizing the kami’s presence. (34)

Romon

A romon is a large gate building, which marks the entrance to the main shrine. From the outside, it seems to have two stories, especially when there is a small balcony running around the building, but actually, it has only one. The central entrance is flanked by covered bays, which contain guardian figure statues known as zuijin . (34)

Hondeny

The honden or shrine’s main hall contains an image or manifestation of the particular kami or spirit worshipped there, thegoshintai . The interior is divided into two parts: the naijin or inner sanctuary and the gejin or outer sanctuary. The naijincontains the goshintai and is almost always closed to anyone except the shrine’s chief priest and even he may not have actually seen the goshintai . Sometimes the doors of the naijin may be opened on special occasions, such as shrine anniversaries. Around the honden is a fence, the tamagaki , which limits the sacred area of typically white gravel or sand and it may even limit the view of the honden from outside. (34)

Haiden

Heiden

The heiden , located between the honden and the haiden , is a building (or simply part of a covered corridor) used for prayers and making offerings ( heihaku ). The term shaden refers to the honden, haiden, and heiden, all together . (34)

Important Shinto Shrines

The most important Shinto shrine is the Ise Grand Shrine dedicated to Amaterasu with a secondary shrine to the harvest goddess Toyouke. Beginning in the 8th century CE, a tradition arose of rebuilding exactly the shrine of Amaterasu at Ise every 20 years to preserve its vitality. The broken-down material of the old temple is carefully stored and transported to other shrines where it is incorporated into their walls.

The second most important shrine is that of Okuninushi at Izumo-taisha. These two are the oldest Shinto shrines in Japan. Besides the most famous shrines, every local community had and still has small shrines dedicated to their particular kami spirits. Even modern city buildings can have a small Shinto shrine on their roof. Some shrines are even portable. Known asmikoshi , they can be moved so that ceremonies can be held at places of great natural beauty such as waterfalls. (27)

Worship & Festivals

The sanctity of shrines means that worshippers must cleanse themselves ( oharai ) before entering them, commonly by washing their hands and mouth with water. Then, when ready to enter, they make a small money offering, ring a small bell or clap their hands twice to alert the kami and then bow while saying their prayer. A final clap indicates the end of the prayer. It is also possible to request a priest to offer one’s prayer. Small offerings might include a bowl of sake (rice wine), rice, and vegetables.

As many shrines are in places of natural beauty such as mountains, visiting these shrines is seen as an act of pilgrimage,Mt. Fuji being the most famous example. Believers sometimes wear Omamori , too, which are small, embroidered sachets containing prayers to guarantee the person’s well-being. As Shinto has no particular view on the afterlife, Shinto cemeteries are rare. Most followers are cremated and interred in Buddhist cemeteries.

The calendar is punctuated by religious festivals to honor particular kami. During these events, portable shrines may be taken to sites linked to a kami, or there are parades of colorful floats, and worshippers sometimes dress to impersonate certain divine figures.

Amongst the most important annual festivals are the three-day Shogatsu Matsuri or Japanese New Year festival, the Obon Buddhist celebration of the dead returning to the ancestral home, which includes many Shinto rituals, and the annual local matsuri when a shrine is transported around the local community to purify it and ensure its future well-being. (27)

“Shinto” by Dr. Kathryn Weinland is adapted from “Shinto” in World Religions by Lumen Learning as published by Florida State College at Jacksonville, licensed CC BY except where otherwise noted.

Licensing and attribution information updated by Kathy Essmiller, 3.16.23. Please contact kathy.essmiller@okstate.edu with corrections or suggestions.

(27) — Shinto by Mark Cartwright published in Ancient History Encyclopedia is licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0 .

(28) — From the Edo Period to Meiji Restoration in Japan by Lumen from Boundless World History is licensed under CC-BY-SA 4.0 .

(34) — Shinto Architecture by Mark Cartwright published in Ancient History Encyclopedia is licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0 .