4.4 Buddhism

Two major branches of Buddhism are generally recognized:

Theravada (“The School of the Elders”)

Theravada has a widespread following in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia (Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Myanmar etc.).

Mahayana (“The Great Vehicle”)

Mahayana is found throughout East Asia (China, Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Singapore, Taiwan etc.) and includes the traditions of Pure Land, Zen, Nichiren Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, Shingon, and Tiantai (Tendai).

In some classifications, Vajrayana —practiced mainly in Tibet and Mongolia, and adjacent parts of China and Russia—is recognized as a third branch, while others classify it as a part of Mahayana.

While Buddhism remains most popular within Asia, both branches are now found throughout the world. Estimates of Buddhists worldwide vary significantly depending on the way Buddhist adherence is defined. Conservative estimates are between 350 and 750 million. Higher estimates are between 1.2 and 1.7 billion. It is also recognized as one of the fastest growing religions in the world. (19)

The Three Jewels

Buddhist schools vary on the exact nature of the path to liberation, the importance and canonicity of various teachings and scriptures, and especially their respective practices. The foundations of Buddhist tradition and practice are the Three Jewels :

- The Buddha

- The Dharma (the teachings)

- The Sangha (the community)

Taking “refuge in the triple gem” has traditionally been a declaration and commitment to being on the Buddhist path, and in general distinguishes a Buddhist from a non-Buddhist.

Other practices may include following ethical precepts; support of the monastic community; renouncing conventional living and becoming a monastic; the development of mindfulness and practice of meditation; cultivation of higher wisdom and discernment; study of scriptures; devotional practices; ceremonies; and in the Mahayana tradition, invocation of buddhas and bodhisattvas. (19)

Early Years of the Buddha and the Four Sights

There is no agreement on when Siddhartha was born. This is still a question mark both in scholarship and Buddhist tradition. Several dates have been proposed, but the many contradictions and inaccuracies in the different chronologies and dating systems make it impossible to come up with a satisfactory answer free of controversy.

Modern scholarship agrees that the Buddha passed away at some point between 410 and 370 BCE, about 140-100 years before the time of Indian Emperor Ashoka’s reign (268-232 BCE). Both scholars and Buddhist tradition agree that the Buddha lived for 80 years. More exactness on this matter seems impossible.

Siddhartha’s caste was the Kshatriya caste (the warrior rulers caste). He belonged to the Sahkya clan and was born in the Gautama family. Because of this, he became to be known as Shakyamuni “sage of the Shakya clan”, which is the most common name used in the Mahayana literature to refer to the Buddha. His father was named Śuddhodana and his mother, Maya. (20)

According to this narrative, shortly after the birth of young prince Gautama, an astrologer visited the young prince’s father and prophesied that Siddhartha would either become a great king or renounce the material world to become a holy man, depending on whether he saw what life was like outside the palace walls.

Śuddhodana was determined to see his son become a king, so he prevented him from leaving the palace grounds. But at age 29, despite his father’s efforts, Gautama ventured beyond the palace several times. In a series of encounters—known in Buddhist literature as the four sights—he learned of:

- The suffering of ordinary people, encountering an old man

- A sick man

- A corpse

- An ascetic holy man, apparently content and at peace with the world

These experiences prompted Gautama to abandon royal life and take up a spiritual quest. (19)

Historical Context

After leaving Kapilavastu, Siddhartha practiced the yoga discipline under the direction of two of the leading masters of that time: Arada Kalama and Udraka Ramaputra. Siddhartha did not get the results he expected, so he left the masters, engaged in extreme asceticism, and five followers joined him. For a period of six years Siddhartha tried to attain his goal but was unsuccessful. After realizing that asceticism was not the way to attain the results he was looking for, he gave up this way of life. (21)

After eating a meal and taking a bath, Siddhartha sat down under a tree of the species ficus religiosa, where he finally attained Nirvana (perfect enlightenment) and became known as the Buddha.

Soon after this, the Buddha delivered his first sermon in a place named Sarnath, also known as the “deer park,” near the city of Varanasi. This was a key moment in the Buddhist tradition, traditionally known as the moment when the Buddha “set in motion the wheel of the law. ” The Buddha explained the middle way between asceticism and a life of luxury, the four noble truths (suffering, its origin, how to end it, and the eightfold path or the path leading to the extinction of suffering), and the impersonality of all beings.

The Buddha’s first disciples joined him around this time, and the Buddhist monastic community, known as Sangha, was established. Sariputra and Mahamaudgalyayana were the two chief disciples of the Buddha. Mahakasyapa was also an important disciple who became the convener of the First Buddhist Council. From Kapilavastu and Sravasti in the north, to Varanasi, Nalanda and many other areas in the Ganges basin, the Buddha preached his vision for about 45 years. During his career he visited his hometown, met his father, his foster mother and even his son, who joined the Sangha along with other members of the Shakya clan. Upali, another disciple of the Buddha, joined the Sangha around this time: he was a Shakya and regarded as the most competent monk in matters of monastic discipline. Ananda, a cousin of the Buddha, also became a monk; he accompanied the Buddha during the last stage of his life and persuaded him to admit women into the Sangha, thus establishing the Bhikkhuni Sangha, the female Buddhist monastic community.

During his career, some kings and other rulers are described as followers of the Buddha. The Buddha’s adversary is reported to be Davadatta, his own cousin, who became a follower of the Buddha and turned out to be responsible for a schism of the Sangha, and he even tried to kill the Buddha.

The last days of the Buddha are described in detail in an ancient text named Mahaparinirvana Sutra. We are told that the Buddha visited Vaishali, where he fell ill and nearly died. Some accounts say that here the Buddha delivered his last sermon. After recovering, the Buddha travelled to Kushinagar. On his way, he accepted a meal from a smith named Cunda, which made him sick and led to his death. Once he reached Kushinagar, he encouraged his disciples to continue their activity one last time and he finally passed away. (21)

Forming of Two Separate Buddhist Lines

About a century after the death of Buddha, during the Second Buddhist Council, we find the first major schism ever recorded in Buddhism: The Mahasanghika School.

Many different schools of Buddhism had developed at that time. Buddhist tradition speaks about 18 schools of early Buddhism, although we know that there were more than that, probably around 25.

A Buddhist school named Sthaviravada (in Sanskrit “ school of the elders ”) was the most powerful of the early schools of Buddhism. Traditionally, it is held that the Mahasanghika School came into existence as a result of a dispute over monastic practice. They also seem to have emphasized the supramundane nature of the Buddha, so they were accused of preaching that the Buddha had the attributes of a god. As a result of the conflict over monastic discipline, coupled with their controversial views on the nature of the Buddha, the Mahasanghikas were expelled, thus forming two separate Buddhist lines: the Sthaviravada and the Mahasanghika .

During the course of several centuries, both the Sthaviravada and the Mahasanghika schools underwent many transformations, originating different schools.

- The Theravada School, which still exists in our day, emerged from the Sthaviravada line, and is the dominant form of Buddhism in Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, Sri Lanka, and Thailand.

- The Mahasanghika School eventually disappeared as an ordination tradition.

- During the 1st century CE, while the oldest Buddhist groups were growing in south and south-east Asia, a new Buddhist school named Mahayana (“ Great Vehicle ”) originated in northern India. This school had a more adaptable approach and was open to doctrinal innovations.

- Mahayama Buddhism is today the dominant form of Buddhism in Nepal, Tibet, China, Japan, Mongolia, Korea, and Vietnam. (20)

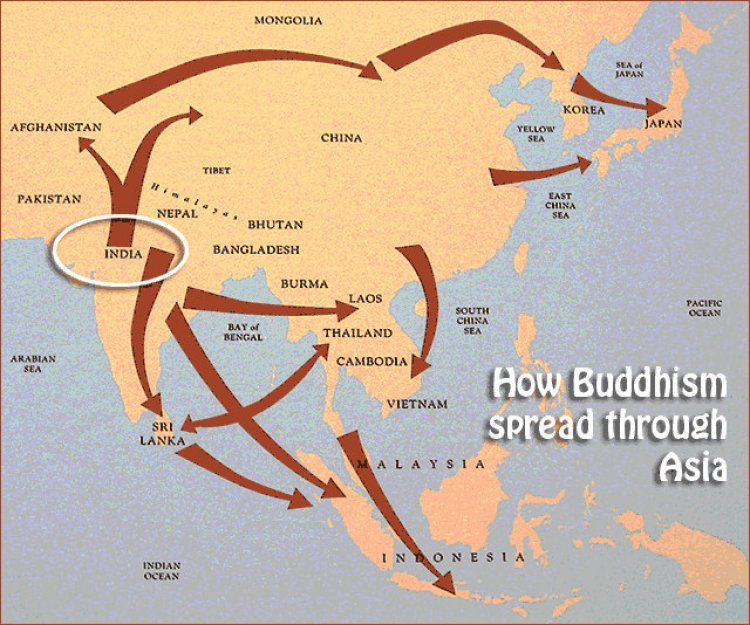

Buddhist Expansion Across Southern Asia

During the time of Ashoka’s reign, trade routes were opened through southern India. Some of the merchants using these roads were Buddhists who took their religion with them. Buddhist monks also used these roads for missionary activity. Buddhism entered Sri Lanka during this time. A Buddhist chronicle known as the Mahavamsa claims that the ruler of Sri Lanka, Devanampiya Tissa, was converted to Buddhism by Mahinda, Ashoka’s son, who was a Buddhist missionary, and Buddhism became associated with Sri Lanka’s kingship. The tight relationship between the Buddhist community and Lankan’s rulers was sustained for more than two millennia until the dethroning of the last Lankan king by the British in 1815 CE.

After reaching Sri Lanka, Buddhism crossed the sea into Myanmar (Burma). Despite the fact that some Burmese accounts say that the Buddha himself converted the inhabitants of Lower and Upper Myanmar, historical evidence suggests otherwise. Buddhism co-existed in Myanmar with other traditions, such as Brahmanism and various local animists’ cults. The records of a Chinese Buddhist pilgrim named Xuanzang (Hsüan-tsang, 602-664 CE) state that in the ancient city of Pyu (the capital of the Kingdom of Sri Ksetra, present day Myanmar), a number of early Buddhist schools were active. After Myanmar, Buddhism travelled into Cambodia, Thailand, Vietnam, and Laos, around 200 CE. Archaeological records from about the 5th century CE support the presence of Buddhism in Indonesia and the Malay Peninsula. (20)

Figure 4.2

Map of how Buddhism spread through Asia

While Buddhism was flourishing all over the rest of Asia, its importance in India gradually diminished. Two important factors contributed to this process: a number of Muslim invasions, and the advancement of Hinduism, which incorporated the Buddha as part of the pantheon of endless gods; he came to be regarded as one of the many manifestations of the god Vishnu. In the end, the Buddha was swallowed up by the realm of Hindu gods, his importance diminished, and in the very land where it was born, Buddhism dwindled to be practiced by very few. (20)

Buddhist Expansion Across Central and East Asia

Expansion into China

Buddhism entered China during the Han dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE). The first Buddhist missionaries accompanied merchant caravans that travelled using the Silk Road, probably during the 1st century BCE. The majority of these missionaries belonged to the Mahayana school.

The initial stage of Buddhism in China was not very promising. Chinese culture had a long-established intellectual and religious tradition and a strong sense of cultural superiority that did not help the reception of Buddhist ideas. Many of the Buddhist ways were considered alien by the Chinese and even contrary to the Confucian ideals that dominated the ruling aristocracy. The monastic order received a serious set of critiques: It was considered unproductive and therefore was seen as placing an unnecessary economic burden on the population, and the independence from secular authority emphasized by the monks was seen as an attempt to undermine the traditional authority of the emperor.

Despite its difficult beginning, Buddhism managed to build a solid presence in China towards the fall of the Han dynasty on 220 CE, and its growth accelerated during the time of disunion and political chaos that dominated China during the Six Dynasties period (220-589 CE). The collapse of the imperial order made many Chinese skeptical about the Confucian ideologies and more open to foreign ideas. Also, the universal spirit of Buddhist teachings made it attractive to many non-Chinese rulers in the north who were looking to legitimate political power. Eventually, Buddhism in China grew strong, deeply influencing virtually every aspect of its culture.

Expansion into Korea

From China, Buddhism entered Korea in 372 CE, during the reign of King Sosurim, the ruler of the Kingdom of Koguryo, or so it is stated in official records. There is archaeological evidence that suggests that Buddhism was known in Korea from an earlier time.

Expansion Into Tibet

The official introduction of Buddhism in Tibet (according to Tibetan records) took place during the reign of the first Tibetan emperor Srong btsan sgam po (Songtsen gampo, 617-649/650 CE), although we know that the proto-Tibetan people had been in touch with Buddhism from an earlier time, through Buddhist merchants and missionaries. Buddhism grew powerful in Tibet, absorbing the local pre-Buddhist Tibetan religions. (20)

Buddhism Today

In the 21st century CE, it is estimated that 488 million (9-10% of the world population) people practice Buddhism. Approximately half are practitioners of Mahayana schools in China and it continues to flourish. The main countries that practice Buddhism currently are China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. Due to the Chinese occupation of Tibet, Tibetan Buddhism has been adopted by international practitioners, notably westerners, in a variety of different countries.

In the 21st century CE, it is estimated that 488 million (9-10% of the world population) people practice Buddhism. Approximately half are practitioners of Mahayana schools in China and it continues to flourish. The main countries that practice Buddhism currently are China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. Due to the Chinese occupation of Tibet, Tibetan Buddhism has been adopted by international practitioners, notably westerners, in a variety of different countries.

‘Socially Engaged Buddhism,’ which originated in 1963 in war-ravaged Vietnam, a term coined by Tchich Nhat Hanh, the international peace activist, is a contemporary movement concerned with developing Buddhist solutions to social, political and ecological global problems. This movement is not divided between monastic and lay members and includes Buddhists from Buddhist countries, as well as western converts. Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar, Bhutan, and Sri Lanka are the major Buddhist countries (over 70% of population practicing) while Japan, Laos, Taiwan, Singapore, South Korea, and Vietnam have smaller but strong minority status.

New movements continue to develop to accommodate the modern world. Perhaps the most notable are the Dalit Buddhist Movement (Dalits are a group of Indians known as the ‘untouchables’ because they fall outside the rigid caste system but who are now gaining respect and status supported by UN); New Kadampa Tradition, led by Tibetan monk Gyatso Kelsang, which claims to be Modern Buddhism focused on lay practitioners; and the Vipassana Movement, consisting of a number of branches of modern Theravada Buddhism which have moved outside the monasteries, focusing on insight meditation.(22)

Buddhist Theology

The Buddha was not concerned with satisfying human curiosity related to metaphysical speculations. The Buddha ignored topics, such as the existence of god, the afterlife, and creation stories. During the centuries, Buddhism has evolved into different branches, and many of them have incorporated a number of diverse metaphysical systems, deities, astrology and other elements that the Buddha did not consider. In spite of this diversity, Buddhism has a relative unity and stability in its moral code. (20)

The Four Noble Truths

The Four Truths, also commonly known as ‘The Four Noble Truths’ explain the basic orientation of Buddhism. They are the truths understood by the ‘worthy ones,’ those who have attained enlightenment or nirvana.

The four truths are dukkha (the truth of suffering); the arising of dukkha (the causes of suffering); the stopping of dukkha (the end of suffering), and the path leading to the stopping of dukkha (the path to freedom from suffering). (23)

Analogy of Understanding the Four Noble Truths

The Four Truths are often best understood using a medical framework:

- Truth 1 is the diagnosis of an illness or condition

- Truth 2 is identifying the underlying causes of it

- Truth 3 is its prognosis or outcome

- Truth 4 is its treatment

Truth 1: The Truth of Suffering

All humans experience surprises, frustrations, betrayals, etc., which lead to unhappiness and suffering. Acknowledging or accepting that we will encounter difficulties in daily life as an inevitable and universal part of life as a human being is the first truth. Within this, there are two types of suffering :

- Natural suffering: Disasters, wars, infections, etc.

- Self-inflicted suffering: Habitual reacting and unnecessary anxiety and regret

Truth 2: The Causes of Suffering

All suffering lies not in external events or circumstances but in the way we react to and deal with them, our perceptions and interpretations. Suffering emerges from craving for life to be other than it is, which derives from the 3 poisons :

- Ignorance (Delusion) of the fact that everything, including the self, is impermanent and interdependent.

- Desire (Greed) of objects and people who will help us to avoid suffering.

- Aversion (Anger) to the things we do not want, thinking we can avoid suffering. We can learn to look at each experience as it happens and be prepared for the next. (23)

Truth 3: The End of Suffering

We hold limiting ideas about ourselves, others, and the world, of which we need to let go. We can unlearn everything from our social conditioning and so bring down all barriers or separations. (23)

Truth 4: The Path that Frees us from Suffering

The mind leads us to live in a dualistic way, but if we are aware of and embrace our habits and illusions, we can abandon our expectations about the ways things should be and instead accept the way they are. We can use mindfulness and meditation to examine our views and gain an accurate perspective.

This Truth contains the Eightfold Path leading out of samsara to nirvana. It consists of:

- Right View: Accepting the fundamental Buddhist teachings

- Right Resolve: Adopting a positive outlook and a mind free from lust, ill-will, and cruelty

- Right Speech: Using positive and productive speech as opposed to lying, frivolous or harsh speech

- Right Action: Keeping the five precepts — refraining from killing, stealing, misconduct, false speech, and taking intoxicants

- Right Livelihood: Avoiding professions which harm others such as slavery of prostitution

- Right Effort: Directing the mind towards wholesome goals

- Right Mindfulness: Being aware of what one is thinking, doing, and feeling at all times

- Right Meditation: Focusing attention in order to enter meditational states

These eight aspects of the path are often divided into 3 groups: Insight (Right View, Right Resolve), morality (Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood), and meditation (Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, Right Meditation).

This eightfold path is not linear, passing from one stage to the next, but cumulative so that ideally all eight factors are practiced simultaneously. (23)

Figure 4.3

Dharma Wheel

Karma and Samsara

In Buddhism, essentially there is no soul. The unresolved karmas manifest into a new form composed of five skandhas (constituent elements of a being) in one of the six realms of samsara. The eventual nirvana (salvation) comes through the annihilation of residual karma, which means the ceasing of the alleged existence of being. The actions with intention (cetana) carried out by the mind, body, and speech and which are driven by ignorance, desire, and hatred lead to implications that tie one down in samsara. Following the eightfold path — the set of eight righteous ways of thinking and acting suggested by Buddha — one can attain nirvana.

Dukkha (Suffering)

Dukkha is defined in more detail as the human tendency to cling to or crave impermanent states or objects, which keep us caught in samsara, the endless cycle of repeated birth, suffering and dying. It is thought that the Buddha taught the Four Truths in the very first teaching after he had attained enlightenment as recorded long after his physical death in the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutra (‘The Discourse that Sets Turning the Wheel of Truth’), but this is still in dispute. They were recognized as perhaps the most important teachings of the Buddha Shakyamuni only at the time the commentaries were written, c. 5th century CE. (23)

Three Schools of Buddhism

Figure 4.4

Map of the Main Modern Buddhist Sects

To clarify this complex movement of spiritual and religious thought and religious practice, it may help to understand the three main classifications of Buddhism to date: Theravada (also known as Hinayana, the vehicle of the Hearers), Mahayana, and Vajrayana.

These are recognized by practitioners as the three main routes to enlightenment (Skt: bodhi, meaning awakening), the state that marks the culmination of all the Buddhist religious paths. The differences between them are as follows:

Click each Path to reveal the description under each one.

It is significant that Theravada texts exclusively concern the Buddha’s life and early teachings; whereas, due to widespread propagation (spreading of the teachings), Mahayana and Vajrayana texts appear in at least six languages. Mahayana texts contain a mixture of ideas, the early texts probably composed in south India and confined to strict monastic Buddhism, the later texts written in northern India and no longer confined to monasticism but lay thinking also. (22)

Mahayana Doctrine of the Bodhisattva

As mentioned, the main tenets of this Mahayana Buddhism are compassion (karuna) and insight or wisdom (prajna). The perfection of these human values culminates in the Bodhisattva, a model being who devotes him or herself altruistically to the service of others, putting aside all self-serving notions; in contrast, is the preceding pursuit of self-interested liberation (Hinayana or Sravakayana). Bodhisattva (Skt; Pali: Bodhisatta) means an enlightened being or one who is oriented to enlightenment. This ideal human being is inspired by the life story of Buddha Shakyamuni who began by generating the wish to attain enlightenment for the sake of all beings in the form of a vow. Then he embarked on a religious life by cultivating the Six Perfections (paramitas).

Early Mahayana texts stipulate that a Bodhisattva can only be male, but later texts allow female Bodhisattvas. The term Bodhicitta is used to describe the state of mind of a Bodhisattva, and there are 2 aspects:

- The relative , a mind directed towards enlightenment, the ceasing of all cravings and attachments

- The absolute , a mind whose nature is enlightenment

A Bodhisattva must place him or herself in the position of others, in order to be selfless and embody compassion: in other words, to exchange him or herself for the other. (22)

Buddhist Texts

Buddhist scriptures and other texts exist in great variety. Different schools of Buddhism place varying levels of value on learning the various texts. Some schools venerate certain texts as religious objects in themselves, while others take a more scholastic approach. Buddhist scriptures are mainly written in Pali, Tibetan, Mongolian, and Chinese. Some texts still exist in Sanskrit and Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit.

The followers of Theravada Buddhism take the scriptures known as the Pali Canon as definitive and authoritative, while the followers of Mahayana Buddhism base their faith and philosophy primarily on the Mahayana sutras and their own vinaya. The Pali sutras, along with other, closely related scriptures, are known to the other schools as the agamas.

Over the years, various attempts have been made to synthesize a single Buddhist text that can encompass all of the major principles of Buddhism. In the Theravada tradition, condensed ‘study texts’ were created that combined popular or influential scriptures into single volumes that could be studied by novice monks. Later in Sri Lanka, the Dhammapada was championed as a unifying scripture.

The Pali Tripitaka, which means ” three baskets ,” refers to:

- Vinaya Pitaka: This contains disciplinary rules for the Buddhist monks and nuns, as well as explanations of why and how these rules were instituted, supporting material, and doctrinal clarification.

- Sutta Pitaka: This contains discourses ascribed to Gautama Buddha.

- Abhidhamma Pitaka: This contains material often described as systematic expositions of the Gautama Buddha’s teachings.

Mahayana Sutras

The Tripitaka Koreana in South Korea, an edition of the Chinese Buddhist canon carved and preserved in over 81,000 wood printing blocks.

The Mahayana sutras are a very broad genre of Buddhist scriptures that the Mahayana Buddhist tradition holds are original teachings of the Buddha. Some adherents of Mahayana accept both the early teachings (including in this the Sarvastivada Abhidharma, which was criticized by Nagarjuna and is, in fact, opposed to early Buddhist thought) and the Mahayana sutras as authentic teachings of Gautama Buddha, and claim they were designed for different types of persons and different levels of spiritual understanding.

The Mahayana sutras often claim to articulate the Buddha’s deeper, more advanced doctrines, reserved for those who follow the bodhisattva path. That path is explained as being built upon the motivation to liberate all living beings from unhappiness. Hence, the name Mahayana (lit., The Great Vehicle). (19)

(19) — Buddhism by Wikipedia for Schools is licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0 .

(20) — Life of the Buddha by Cristian Violatti published in Ancient History Encyclopedia is licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0 .

(21) — Siddhartha Gautama by Cristian Violatti published in Ancient History Encyclopedia is licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0 .

(22) — Mahayana Buddhism by Charley Thorp published in Ancient History Encyclopedia is licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0 .

(23) — Four Noble Truths by Charley Thorp published in Ancient History Encyclopedia is licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0 .