6.1 Modern World History Begins in Asia

As mentioned in the Introduction, civilization began in India about 4,600 years ago and China’s recorded history began about 2000 BCE. Based on irrigated rice agriculture, the population of China grew to 50 to 60 million people as early as 2,000 years ago. This population was originally divided into several small kingdoms whose ruling families were connected through political marriages. Beginning in 221 BCE, the Chinese created an empire that lasted over two thousand years under a series of more than a dozen dynasties. The early imperial governments began construction of the called Long Walls, and dug the Grand Canal to connect the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers in the sixth century CE. China held a monopoly on the creation of silk, which was a closely-held state secret for millennia, and led the world in iron, copper, and porcelain production as well as a variety of technological inventions including the compass, gunpowder, paper-making, mechanical clocks, and moveable type printing.

The social stability that allowed Chinese culture to produce these innovations was based on not only the imperial form of government, but on an elaborate system of professional civil service. The early establishment of a professional administrative class of “scholar-officials” was a remarkable element of imperial Chinese rule that made it more stable, longer-lasting, and at least potentially less oppressive than empires in other parts of the world. The imperial courts sent thousands of highly-educated administrators throughout the empire and China was ruled not by hereditary nobles or even elected representatives, but by a class of men who had received rigorous training and had passed very stringent examinations to prove themselves qualified to lead.

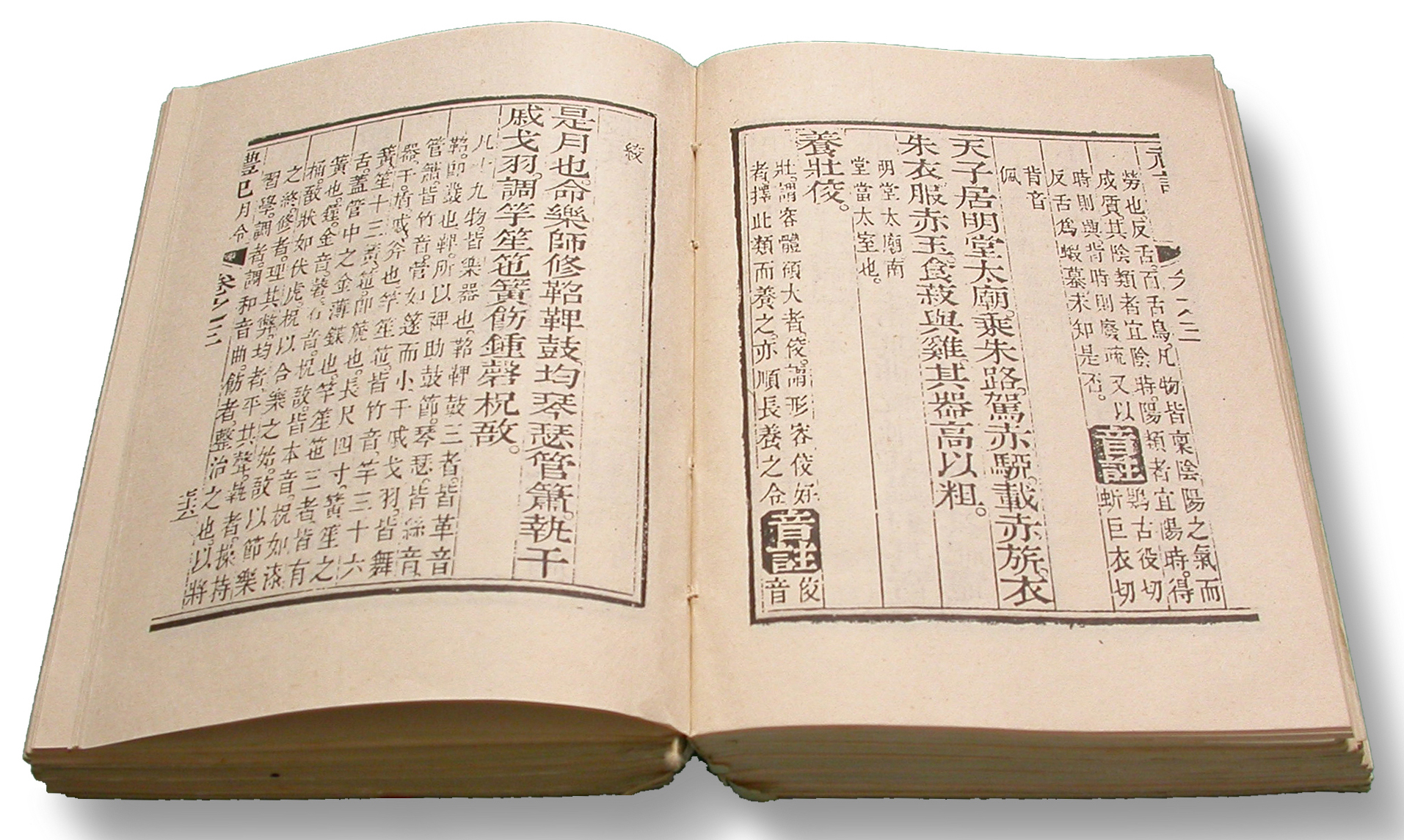

Young men who wanted to become civil administrators in China entered training schools that concentrated on calligraphy and the teachings of Confucius. Calligraphy in China equaled literacy. Chinese language is based on characters rather than on an alphabet, and is said to be the world’s oldest continually-used writing system. A dictionary published in 1039 CE listed 53,525 characters, and a 2004 Chinese dictionary included 106,230. Most Chinese words are made of one or more characters. For comparison, the English alphabet uses 26 letters and the average American has a practical vocabulary of about 10,000 words. While a foreigner learning Chinese today would be judged proficient on the national exam (the Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi or HSK) with a vocabulary of about 9,000 words, they would need to know the 2,865 characters that made up these words in order to study at a Chinese university or work in a Chinese business.

In addition to literacy, civil service training focused on the philosophy of Confucius, a Chinese philosopher who had lived from 551 to 479 BCE. Kong Fuzi (Master Kong—he is known as “Confucius” in the West) taught principles derived from what he described as old Chinese classics. Confucius claimed he was not so much creating a new philosophy as preserving and combining the best traditions of the past, which was very appropriate in a culture devoted to reverence of its ancestors. He traveled as a teacher and advisor of local rulers, and his practical philosophy spread. Confucian ideas about conduct focus on five basic virtues: seriousness, generosity, sincerity, diligence, and kindness.

When a student asked him “Is there any one word that could guide a person throughout life?” Confucius replied, “How about ‘reciprocity’! Never impose on others what you would not choose for yourself.” (Analects XV.24) The Chinese, who valued silver higher than gold, called this the silver rule. Confucian social morality is based on this reciprocity and on empathy and understanding others rather than on divinely ordained rules. Although Confucius occasionally talked about heaven and an afterlife, his moral system was not based on the idea of supernatural rewards and punishments. Confucian morality is secular rather than religious, which left room for the Emperor to be a representative of Divinity and claim “the Mandate of Heaven” without the Chinese Empire becoming a theocracy.

Centuries after his death, Confucian ideas became the basis of civil service education in imperial China. Scholars would travel to testing centers and sit for exams that often took days to complete. They brought food and a bedroll and remained in their small testing cells until they had completed the exam. There were four increasingly-difficult levels of testing: County, District, Province, and Imperial. The highest exam was administered by the emperor himself and passing it qualified a scholar for assignments in the imperial court. The exams were extremely difficult and at each level more people failed than passed. But the exams were also democratic in a way: even a scholar from a poor family could take the exam if he could educate himself; success on the top exam was a ticket to the highest levels of imperial society. Over the centuries, the scholars became an upper class in Chinese society, a gentry based on educational merit rather than merely on birth or wealth. Although there were times when the system was corrupted, for most of its history Chinese society was run by educated men rather than by nobles who had inherited their positions.

Confucianism is not a perfect philosophy, since it accepted and even reinforced certain societal injustices. Confucius incorporated traditional Chinese ancestor-worship into his system, which implied a degree of sacredness for ancestral practices. For this reason, Confucian principles perpetuated and exacerbated the oppression of women, who had no standing in the male-dominated family structure. Girls were considered an expense to their birth families, since they only became valuable when they married and bore sons for their new families. Female infanticide has been a problem throughout Chinese history, as was, until the last century, the practice of foot-binding, which rendered generations of Chinese women crippled and semi-mobile for the sake of what amounted to a fetish of Chinese fashion.

But despite its faults, Confucian civil service insured that for much of its history the Chinese empire, its various districts and regions, and even small communities were run by educated administrators and magistrates rather than by random rulers who achieved power by conquest or inheritance.

The Chinese Empire did face conquest several times, but Chinese culture and social organization managed to absorb its conquerors. In 1271, the Mongol leader Kublai Khan, the grandson of Genghis Khan, defeated the Chinese army and established the Yuan dynasty, which that lasted 98 years until 1368. Although Kublai Khan never completely conquered China despite 65 years of struggle, Yuan rule marked the first time the Chinese Empire was controlled by foreigners. The Khan distrusted Confucian officials, but he did not completely replace them as regional administrators. Still, through the Yuan dynasty, China was exposed to foreign cultures, especially Islamic cartography, mathematics, astronomy, medicine, food, and clothing, while likewise, the West encountered Chinese culture and technological advances in a serious way. The Silk Road, the ancient trade route connecting China with Europe had languished for several centuries under the Islamic Caliphate in the Middle East; it was reestablished and in 1271 the Venetian merchants Niccolo, Maffeo, and Marco Polo visited Kublai Khan at his summer palace in Shangdu (Xanadu). The Mongol rulers also patronized China’s new printing industry, which helped spread the idea of moveable type printing into Europe.

Despite the fact that China’s Mongol Yuan rulers abandoned many of their own traditions and adopted the ways of the people they had conquered, the ethnic Han Chinese majority continued to resent being ruled by foreigners. Along with exposure to foreign cultures, the Mongols’ reopening of the Silk Road brought foreign diseases to China. Bubonic Plague, the “Black Death” that killed a quarter of the European population in the 14th century, actually hit China first. The plague began in central Kyrgystan and killed up to 25 million people in China in the 1330s and 1340s, about 15 years before it first arrived in Constantinople. As in Europe, famine and social chaos followed the plague when agriculture failed to produce enough to feed the survivors.

A young man named Zhu Yuanzhang, born during the plague years, watched his entire family die in famines that swept through southern China in the 1340s. After taking refuge in a Buddhist monastery, Zhu joined local rebels when the monastery was destroyed by Yuan forces trying to contain a local insurrection. Zhu joined forces with a rebel army called the Red Turbans and rose quickly through the ranks. Zhu married the daughter of the founder of the Red Turbans and inherited his leadership position after eliminating several rival generals. In 1356, the 28-year old general conquered the ancient city of Nanjing and made it his base. In 1368, Zhu led his troops north and chased the Yuans out of their capital of Dadu (now Beijing). The Mongols retreated to Mongolia and Zhu claimed the Mandate of Heaven and declared himself the first emperor of the Ming (brilliant) Dynasty.

Zhu Yuanzhang called himself the Hongwu Emperor (expansive and martial) and made Nanjing his capital. Imperial titles like “Hongwu” relate to the reign of each emperor, in which they declare the nature of their particular rule. These titles are not the actual name of the emperor, but this is how they are known in Chinese history.

Hongwu ruled for thirty years and tried to return the empire to its ethnic Chinese roots. Hongwu issued decrees abolishing Mongol dress and requiring people to abandon their Mongol-influenced names in favor of traditional Han Chinese names. Administration of the empire by Confucian scholars was reinstated, along with the elaborate system of civil service examinations. Remembering the suffering and famines during his youth, partly caused by the flooding of the Yangtze River, Hongwu promoted public works and infrastructure projects including new dikes and irrigation systems to serve an agricultural system dominated by paddy rice. He organized the building or repair of nearly 41,000 reservoirs and planted over a billion trees in his land reclamation program. Hongwu distributed land to peasants and forced many to move to less populated areas. During his three-decade reign, China’s population recovered from plague and famine, and grew from 60 to 100 million.

Hongwu had fought his way to prominence by eliminating his rivals and trusting only his family. But when his first son, the crown prince, died, Hongwu left his throne to the son of his favorite son, rather than picking one of his other sons.. Hongwu’s grandson became emperor at 20, but his reign was a short one. His uncle Zhu Di, the emperor’s younger son, had been passed over for the crown but remained prince of a northern territory around Dadu, the previous Yuan capital close to the Mongol border. In 1402 Zhu Di overthrew his nephew and declared himself the Yongle (perpetual happiness) Emperor.

Yongle tried to erase the memory of his rebellion by purging a large number of Confucian scholars in the capital of Nanjing and moving the government to his home in Dadu, which he renamed Beijing. Yongle ruled through an extensive network of court eunuchs who formed his palace guard and secret police. Yongle repaired and reopened China’s Grand Canal, the 1,104-mile waterway that linked the Yellow and Yangxi Rivers and enabled the new capital to receive rice shipments from the south. Between 1406 and 1420, he also directed 100,000 artisans and 1 million laborers in building the Forbidden City in Beijing as a permanent imperial residence.

One of Yongle’s most trusted subordinates was the eunuch admiral Zheng He (1371-1433), the son of a Muslim soldier from southwestern China. At the age of ten Zheng He was captured, castrated, and sent to serve Prince Zhu Di in Dadu. Castration was a common practice throughout the ancient and early modern world, used in China to insure loyalty by eliminating conflict between family and duty. Educated in the prince’s household, Zheng He became a loyal soldier and later a general. Zheng He helped Zhu Di depose his nephew and take control of the empire, and the new Yongle Emperor appointed Zheng He admiral of his fleet and sent him on seven expeditions between 1405 and 1430.

Zheng He’s first expedition left China in July 1405 with 62 large ships, over 200 smaller ships, and 28,000 soldiers. The largest ships were 425 feet long, over six times the length of the 65-foot caravels the Spanish and Portuguese would use on their explorations nearly a century later. China’s four-decked, 1,500-ton flagships had shallow drafts to allow them to navigate in river estuaries and watertight bulkheads to protect them from sinking. Their nine masts were up to two hundred feet tall and fitted with rattan sails.

Zheng He’s fleet was not interested in establishing colonies, but in exacting tribute and opening trade relationships throughout South Asia. The fleet traded for ivory, spices, ointments, exotic woods, giraffes, zebras, and ostriches; while also demanding tribute from the rulers of nations like Sumatra and Sri Lanka. Often, when local leaders seemed unwilling to submit, Zheng He seized them and brought them to Beijing where they could be convinced of the overwhelming power of the Chinese Empire. Among the places Zheng visited were Bangkok, Java, Melaka, Burma, the east and west coasts of India, Hormuz in the Persian Gulf, Jedda on the Red Sea, and Mogadishu and Mombasa on the east coast of Africa. Ninety-five delegations from Southeast Asia and other more distant nations reached the Yongle Emperor’s court during his 22-year reign, and he established a College of Translators to handle all the correspondence he received from foreign contacts. Zheng He’s seven expeditions extracted tribute from many neighboring kingdoms, and Yongle trusted him so completely that he sent Zheng He blank scrolls with his imperial seal on them, to use in whatever way he chose.

For many centuries the voyages of Zheng He were not featured in histories of China, even in China itself. As historians have rediscovered these expeditions, the superiority of Chinese naval technology has challenged the belief that western nations were the first to establish maritime power. One of the most interesting questions about Zheng He’s voyages is, “Why did they end?” China did not establish offshore colonies, perhaps partly because there was so much territory available on the empire’s northern and western frontiers. China’s rapidly-growing population was a ready market for most of the empire’s farm products and manufactures, and the international trade that interested China already found its way to the empire without much effort on China’s part. And unlike European kings, the Yongle emperor was not interested in evangelizing Confucianism or Buddhism to the rest of the world—the Spanish and Portuguese, in particular, wanted to convert the world to Catholic Christianity, which became not only a goal but a justification for conquest and colonization.

When the Yongle Emperor’s son and grandson inherited the throne, Zheng He’s expeditions gradually became less of a priority. After a final voyage in 1433, expeditions were halted and the fleet was retired and ultimately burned. Ending China’s navy was one of the major changes made by Yongle’s descendants. The burning of the Chinese fleet left a power vacuum in the South China Sea, which in the sixteenth century was filled by Japanese and Chinese coastal pirates. Finally, shortly after Yongle and Zheng He’s deaths, China was challenged from the north again. Sixteen years after Zheng He’s final expedition, Yongle’s great grandson, the sixth Ming emperor, was captured and held hostage by Mongol raiders in 1449.

The alarmed Chinese turned their attention to their border defenses and rebuilt the crumbling Long Walls into a 1,550-mile long fortification with hundreds of guard towers. The Long Walls had existed since the beginning of the Chinese Empire, but had failed to hold off Mongol invaders. Under the Mings the Great Wall was improved and extended, especially around the capital of Beijing and the agricultural heartland in the Liaodong Province north of the Korean Peninsula. These defenses enabled the Chinese population to rise from 100 million in 1500 to 160 million in 1600. However, the threat of a Manchurian land invasion from the north was taken very seriously, to the detriment of authorizing further naval expeditions. China’s turning away from the ocean was a momentous decision in world history, opening the door for Southeast Asians, Muslims, and eventually Europeans to dominate the Indian Ocean and the Pacific.

As the generations passed, Ming emperors and their courts became increasingly isolated in the Forbidden City the Yongle Emperor had built. Some were incompetent rulers, others were just uninterested in ruling. Similar to other new imperial dynasties, the Ming Dynasty began by concentrating political power in the Emperor and in the civil servants chosen through the Confucian examination process. As time passed, a ruling class grew and power shifted as the new elite protected their lands and possessions from taxation. Corrupt officials siphoned funds designated for public works into their own pockets and infrastructure such as dams and dikes crumbled. Eventually, irrigation systems failed and peasants died in widespread famines.

At the same time, Manchuria was being unified under strong military leaders who had adopted Chinese ways and who even employed Confucian administrators. In 1644, a Ming government official dealing with a local peasant insurrection that threatened Beijing asked the Manchurians for military aid. Of course, once the Manchu armies were past the Wall, there was no way to send them back. They took control of Beijing and declared the end of the Ming Empire and the beginning of a new dynasty, the Qing (pure).

We will return later to the history of China, the Qing Dynasty, and what came after. For now, the point of beginning modern world history with China is that in terms of population and economic power, it was the center of the world in 1500 when our survey of Modern World History begins. In 1500, the Chinese population was growing rapidly, the Ming Empire had a standing army of over a million soldiers and the Chinese navy of Zheng He had recently projected the empire’s power throughout Asia. The Chinese economy produced one quarter of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 1500, followed by India which produced nearly another quarter. In comparison, the fourteen nations of western Europe produced just about half of China’s GDP or only one-eight of the global total production. The largest European economy, in Italy, produced only about one-sixth of China’s output.

The Ming Empire’s population in 1500 was about 125 million. The next largest empires were Southern India’s Vijayanagara Empire (16 million), followed by the Inca Empire of South America (12 million), the Ottoman Empire (11 million), the Spanish Empire (about 8.5 million), and the Ashikaga Shogunate of Japan (8 million). Keep the immense mass of China and the gravity exerted by its economy in mind as we move on to discuss events like the creation of a Spanish colonial empire in the Americas—Spanish-American mines produced the silver that accidentally became the world’s currency, filling not only the treasuries Europe, but also that of China in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Primary Source Supplement #1: 99 Famous Sayings attributed to Confucius:

Confucius (551-479 BCE) is the most famous philosopher of China. The teachings of Kong Fuzi (Master Kong—known as “Confucius” in the West) were the basis of regulating relationships in Chinese society. For centuries, would-be civil servants needed to study Confucian precepts for the examinations used to choose imperial administrators. Much of Confucian teaching comes in the form of short aphorisms. Drawing on ancient Chinese customs of patriarchy, filial piety, and veneration of ancestors, Confucianism was extremely chauvinistic and led to centuries of oppression of women in Chinese culture–when Confucius said “man” or “he”, he actually meant it. However, that doesn’t mean Confucius didn’t make some thought-provoking statements, if we expand them to include all people. Here are 99 aphorisms considered noteworthy by contemporary collectors of quotes :

“The man who says he can, and the man who says he cannot, are both correct.”

“Your life is what your thoughts make it.”

“Real knowledge is to know the extent of one’s ignorance.”

“The man who asks a question is a fool for a minute, the man who does not ask is a fool for life.”

“The journey with a thousand miles begins with one step.”

“Choose a job you love, and you will never have to work a day in your life.”

“You are what you think.”

“Looking at small advantages prevents great affairs from being accomplished.”

“All people are the same; only their habits differ.”

“Learn avidly. Question it repeatedly. Analyze it carefully. Then put what you have learned into practice intelligently.”

“We have two lives, and the second begins when we realize we only have one.”

“If you are the smartest person in the room, then you are in the wrong room.”

“Act with kindness but do not expect gratitude.”

“Worry not that no one knows you; seek to be worth knowing.”

“The man who moves a mountain begins by carrying away small stones.”

“When it is obvious that the goals cannot be reached, don’t adjust the goals, adjust the action steps.”

“The essence of knowledge is, having it, to use it.”

“One joy dispels a hundred cares.”

“When you see a good person, think of becoming like her/him. When you see someone not so good, reflect on your own weak points.”

“I slept and dreamt life is beauty, I woke and found life is duty.”

“They must often change who would remain constant in happiness and wisdom.”

“Don’t complain about the snow on your neighbor’s roof when your own doorstep is unclean.”

“A lion chased me up a tree, and I greatly enjoyed the view from the top.”

“Be not ashamed of mistakes and thus make them crimes.”

“The superior man is modest in his speech but exceeds in his actions.”

“Be strict with yourself but least reproachful of others and complaint is kept afar.”

“Roads were made for journeys not destinations.”

“No matter how busy you may think you are you must find time for reading or surrender yourself to self-chosen ignorance.”

“Think of tomorrow, the past can’t be mended.”

“Respect yourself and others will respect you.”

“To be wronged is nothing, unless you continue to remember it.”

“I hear and I forget. I see and I remember. I do and I understand.”

“By nature, men are nearly alike; by practice, they get to be wide apart.”

“Learn as if you were not reaching your goal and as though you were scared of missing it.”

“Never contract friendship with a man that is not better than thyself.”

“He who knows all the answers has not been asked all the questions.”

“Those who cannot forgive others break the bridge over which they themselves must pass.”

“Those who know the truth are not equal to those who love it.”

“The superior man thinks always of virtue; the common man thinks of comfort.”

“The superior man acts before he speaks, and afterwards speaks according to his action.”

“Success depends upon previous preparation, and without such preparation there is sure to be failure.”

“Only the wisest and stupidest of men never change.”

“Study the past if you would define the future.”

“Our greatest glory is not in never falling, but in rising every time we fall.”

“Learning without thought is labor lost; thought without learning is perilous.”

“Do not impose on others what you yourself do not desire.”

“The superior man makes the difficulty to be overcome his first interest; success only comes later.”

“If you make a mistake and do not correct it, this is called a mistake.”

“Education breeds confidence. Confidence breeds hope. Hope breeds peace.”

“To see the right and not to do it is cowardice.”

“Virtuous people often revenge themselves for the constraints to which they submit by the boredom which they inspire.”

“He who acts with a constant view to his own advantage will be much murmured against.”

“The superior man is distressed by the limitations of his ability; he is not distressed by the fact that men do not recognize the ability that he has.”

“To see what is right and not to do it is want of courage, or of principle.”

“When anger rises, think of the consequences.”

“To know what you know and what you do not know, that is true knowledge.”

“I want you to be everything that’s you, deep at the center of your being.”

“The object of the superior man is truth.”

“When you have faults, do not fear to abandon them.”

“To go beyond is as wrong as to fall short.”

“If you think in terms of a year, plant a seed; if in terms of ten years, plant trees; if in terms of 100 years, teach the people.”

“If you look into your own heart, and you find nothing wrong there, what is there to worry about? What is there to fear?”

“It does not matter how slowly you go as long as you do not stop.”

“Virtue is not left to stand alone. He who practices it will have neighbors.”

“Better a diamond with a flaw than a pebble without.”

“The superior man does not, even for the space of a single meal, act contrary to virtue. In moments of haste, he cleaves to it. In seasons of danger, he cleaves to it.”

“The will to win, the desire to succeed, the urge to reach your full potential: these are the keys that will unlock the door to personal excellence.”

“Go before the people with your example and be laborious in their affairs.”

“When we see persons of worth, we should think of equaling them; when we see persons of a contrary character, we should turn inwards and examine ourselves.”

“If we don’t know life, how can we know death?”

“The expectations of life depend upon diligence; the mechanic that would perfect his work must first sharpen his tools.”

“He who speaks without modesty will find it difficult to make his words good.”

“What you do not want done to yourself, do not do to others.”

“Without feelings of respect, what is there to distinguish men from beasts?”

“You cannot open a book without learning something.”

“A gentleman would be ashamed should his deeds not match his words.”

“When a person should be spoken with, and you don’t speak with them, you lose them. When a person shouldn’t be spoken with and you speak to them, you waste your breath. The wise do not lose people, nor do they waste their breath.”

“To see and listen to the wicked is already the beginning of wickedness.”

“Wherever you go, go with all your heart.”

“Give a bowl of rice to a man and you will feed him for a day. Teach him how to grow his own rice and you will save his life.”

“Study the past, if you would divine the future.”

“It is more shameful to distrust our friends than to be deceived by them.”

“Life is really simple, but we insist on making it complicated.”

“Silence is a true friend who never betrays.”

“By three methods we may learn wisdom: first, by reflection, which is noblest; second, by imitation, which is easiest; and third by experience, which is the bitterest.”

“Wisdom, compassion, and courage are the three universally recognized moral qualities of men.”

“Death and life have their determined appointments; riches and honors depend upon heaven.”

“Everything has beauty, but not everyone sees it.”

“The more man meditates upon good thoughts, the better will be his world and the world at large.”

“He who learns but does not think, is lost! He who thinks but does not learn is in great danger.”

“If you don’t want to do something, don’t impose on others.”

“It is easy to hate and it is difficult to love. This is how the whole scheme of things works. All good things are difficult to achieve and bad things are very easy to get.”

“The strength of a nation derives from the integrity of the home.”

“The superior man understands what is right; the inferior man understands what will sell.”

“Never give a sword to a man who can’t dance.”

“We should feel sorrow, but not sink under its oppression.”

“Imagination is more important than knowledge.”

“When you know a thing, to hold that you know it; and when you do not know a thing, to allow that you do not know it – this is knowledge.”

Source: http://www.quoteambition.com/famous-confucius-quotes/

Primary Source Supplement #2: Zheng He’s Voyages

The Ming Shi-lu (The Veritable Records of the Ming) are the imperial annals of the Ming Dynasty emperors (1368-1644). The National University of Singapore has published an online archive of over 2,800 pages of Geoff Wade’s translations of the annals . They contain a wealth of information about Ming China, including twenty-two references to Chinese Admiral Zheng He and his diplomatic voyages, dated from July 1405 to March 1431. Here are some entries, describing Zheng He’s missions and incidents related to them. In several, Zheng is described as being sent as an emissary to fan countries. The Mandarin word fan translates roughly as ordinary or mortal, suggesting the attitude of the Chinese emperors toward foreign nations and their rulers. The English word “enfeoff” is also not well known. It means to grant something to a lesser lord or noble, like a fiefdom. Entries are dated by imperial era dates, with western calendar dates in parentheses:

“The eunuch Zheng He and others were sent to take Imperial orders of instruction to the various countries in the Western Ocean, and to confer upon the kings of those countries patterned fine silks and variegated thin silks interwoven with gold thread, as appropriate.”

Yongle: Year 3, Month 6, Day 15 (11 Jul 1405)

“The Eunuch Director Zheng He who had been sent to the various countries of the Western Ocean, returned, bringing the pirate Chen Zuyi and others in fetters. Previously, when he had arrived at Old Port, he came across Zuyi and so on and sent people to bring them to negotiated pacification. Zuyi and the others feigned surrender but secretly plotted to attack the Imperial army. He and the others found out about this and, marshalling the troops, prepared defenses. When the forces led by Zuyi attacked, He sent his troops out to do battle. Zuyi suffered a great defeat. Over 5,000 of the bandit gang were killed, while ten of the bandit ships were burnt and seven captured. Further, two false bronze seals were seized and three prisoners, including Zuyi, were taken alive. When they arrived at the capital, it was ordered that all the prisoners be beheaded.”

Yongle: Year 5, Month 9, Day 2 (2 Oct 1407)

“The eunuch Zheng He and others, who had been sent as envoys to the various countries in the Western Ocean, returned and presented Yalie Kunaier, the captured king of the country of Sri Lanka, and his family members. Previously, He and the others had been sent as envoys to the various fan countries. However, when they reached Sri Lanka, Yalie Kunaier was insulting and disrespectful. He wished to harm He, but He came to know of this and left. Yalie Kunaier also acted in an unfriendly way to neighboring countries and repeatedly intercepted and robbed their envoys. All the fan countries suffered from his actions. When He returned, he again passed Sri Lanka and the king enticed him to the country. The king then had his son Nayan demand gold, silver and precious objects, but He would not give these to him. The king then secretly dispatched over 50,000 fan troops to rob He’s ships. They also felled trees to create obstructions and impede He’s route of return, so that he could not render assistance. He and the others found out about this and they gathered their force and set off back to their ships. However, the route had already been blocked. He thus spoke to his subordinates, saying: ‘The majority of the troops have already been dispatched. The middle of the country will be empty.’ He also said: ‘Our merchants and troops are isolated and nervous and will be unable to act. If they are attacked by surprise, the attackers will achieve their purpose.’ Thus, he secretly ordered persons to go to the ships by another route with orders that the government troops were to fight to the death in opposing the attackers. He then personally led 2,000 of his troops through a by-path and attacked the royal city by surprise. They took the city and captured alive Yalie Kunaier, his family members and chieftains. The fan army returned and surrounded the city and several battles were fought, but He greatly defeated them. He and the others subsequently returned to the Court. The assembled ministers requested that the king be executed. The Emperor pitied the king for his stupidity and ignorance and leniently ordered that he and the others be released and given food and clothing. The Ministry of Rites was ordered to deliberate on and select a worthy member of the family to be established as the country’s king in order to handle the country’s sacrifices.”

Yongle: Year 9, Month 6, Day 16 (6 Jul 1411)

“As the envoys from the various countries of Calicut, Java, Melaka, Champa, Sri Lanka, Mogadishu, Liushan, Nanboli, Bulawa, Aden, Samudera, Malin, Lasa, Hormuz, Cochin, Nanwuli, Shaliwanni and Pahang, as well as from the Old Port Pacification Superintendency, were departing to return home, suits of clothing made from patterned fine silks were conferred upon all of them. The eunuch Zheng He and others were sent with Imperial orders as well as embroidered fine silks, silk gauzes, variegated thin silks and other goods to confer upon the kings of these countries, to confer a seal upon Keyili, the king of the country of Cochin, and to enfeoff a mountain in his country as the ‘Mountain Which Protects the Country’.

The Emperor personally composed and conferred an inscription for the tablet, as follows:

‘The civilizing influences and Heaven and Earth intermingle. Everything which is covered and contained has been placed in the charge of the Moulder, who manifests the benevolence of the Creator. The world does not have two ultimate principles and people do not have two hearts. They are sorrowful or happy in the same way and have the same feelings and desires. How can they be divided into the near and the distant!

One who is outstanding in ruling the people should do his best to treat the people as his children. The Book of Odes says: `The Imperial domain stretches for thousands of li, and there the people have settled, while the borders reach to the four seas.’ The Book of Documents says: ‘To the East, extending to the sea, to the West reaching to the shifting sands and stretching to the limits of North and South, culture and civilizing influences reach to the four seas.’ I rule all under Heaven and soothe and govern the Chinese and the yi. I look on all equally and do not differentiate between one and the other. I promote the ways of the ancient Sagely Emperors and Perspicacious Kings, so as to accord with the will of Heaven and Earth. I wish all of the distant lands and foreign regions to have their proper places.

Those who respond to the influences and move towards culture are not singular. The country of Cochin is far away in the South-west, on the shore of the vast ocean, further distant than the other fan countries. It has long inclined towards Chinese culture and been accepting of civilizing influences. When the Imperial orders arrived, the people there went down on their hands and knees and were greatly excited. They loyally came to allegiance and then, looking to Heaven, they bowed and all said: `How fortunate we are that the civilizing influences of the Chinese sages should reach us. For the last several years, the country has had fertile soil, and the people have had houses in which to live, enough fish and turtles to eat, and enough cloth and silk to make clothes. Parents have looked after their children and the young have respected their elders. Everything has been prosperous and pleasing. There has been no oppression or contention. In the mountains no savage beasts have appeared and in the streams no noxious fishes have been seen. The sea has brought forth treasures and the forests have produced excellent woods. Everything has been in bountiful supply, several times more bountiful than in ordinary times. There have been no destructive winds, and damaging rains have not occurred. Confusion has been eliminated and there is no evil to be found. This is all indeed the result of the civilizing influences of the Sage.’ I possess but slight virtuous power. How could I have been capable of this! Is it not the elders and people who brought this about? I am now enfeoffing Keyili as king of the country and conferring upon him a seal so that he can govern the people. I am also enfeoffing the mountain in the country as ‘Mountain Which Protects the Country’. An engraved tablet is to be erected on this mountain to record these facts forever. It will also be engraved as follows: The high peak which rules the land, guards this ocean state, It spits fire and fumes, bringing great prosperity to the country below, It brings rain and sunshine in a timely way, and soothes away troubles, It brings fertile soil and drives off evil vapors, It shelters the people, and eliminates calamities and disharmony, Families are joyful together, and people have plenty throughout the year, The mountain’s height is as the ocean’s depths! This poem is inscribed to record all for prosperity.”

Yongle: Year 14, Month 12, Day 10 (28 Dec 1416)

“The envoys from the 16 countries of Hormuz and so on departed on their return to their countries. Paper money and biao-li of silks were conferred upon them. In addition, the Eunuch Director Zheng He and others were sent with Imperial orders, together with brocades, fine silks, silk gauzes, damasks and thin silks to confer upon the kings of these countries. They departed together with the envoys.”

Yongle: Year 19, Month 1, Day 30 (3 Mar 1421)

“The Eunuch Director Zheng He and others were sent with an Imperial proclamation to go and instruct the various fan countries. The proclamation read: ‘I have respectfully taken on the mandate of Heaven and reverently inherited the Great Rule from the Taizu Gao Emperor, the Taizong Wen Emperor and the Renzong Zhao Emperor. I rule over the ten thousand states, manifest the supreme benevolence of my ancestors and spread peace to all things. I have already issued a general amnesty to all under Heaven and declared the commencement of the Xuande reign. All has begun anew. You, the various fan countries far across the ocean, will not yet have heard. Now I am especially sending the Eunuch Directors Zheng He and Wang Jinghong carrying this proclamation with which to instruct you. You must all respect and accord with the Way of Heaven, care for your people and keep them in peace. Thus will you all enjoy the prosperity of Great Peace.’ Variegated silks, as appropriate, were to be conferred upon the rulers or chiefs of all 20 countries through which the eunuchs were to pass, including Hormuz, Sri Lanka, Calicut, Melaka, Cochin, Bulawa, Mogadishu, Nanboli, Samudera, Lasa, Liushan, Aru, Ganbali, Aden, Zuofaer, Zhubu, Jiayile and so on, as well as the Old Port Pacification Superintendency.

Xuande: Year 5, Month 6, Day 9 (29 Jun 1430)

“The chieftain Wubaochina and others from the country of Melaka, arrived at the Court. They advised that the king of their country wanted to personally come to Court and offer tribute, but that he had been obstructed by the king of the country of Siam. They also said that Siam had long wanted to invade their country and that their country wanted to memorialize but had had no one who could write the memorial. At this time, the king had ordered that these three ministers secretly attach themselves to a Samuderan tribute ship and come to Court. They requested that the Court send people to instruct the king of Siam to no longer oppress or mistreat their country and that thereby they would be unendingly grateful for the Court’s grace. The Emperor ordered the Auxiliary Ministry of Rites to confer rewards upon Wubaochina and the others and to send them back to their country with the ships of the eunuch director Zheng He. Zheng He was ordered to take Imperial orders of instruction for the king of the country of Siam as follows:

‘I rule all under Heaven and look on all equally. You have been able to respect the Court and have repeatedly sent envoys to come to Court and offer tribute. I am pleased with your service. However, recently, it has been heard that the king of the country of Melaka wanted to personally come to Court, but was obstructed by you. In my opinion, this certainly cannot have been your will, king. Rather, it must have been some of your attendants, who are unable to think deeply about things, who have obstructed avenues and started strife with neighboring states. How can such actions be a way to long maintain prosperity? You, king should respect my orders, develop good relations with your neighbors, examine and instruct your subordinates and not act recklessly or aggressively. Then it will be seen that you are able to respect Heaven and serve the superior, protect the country and the people’s peace and maintain good relations with neighboring states. This will accord with my will of looking on all equally.’

The Ministry of Rites said:

‘There are precedents for conferring rewards on tribute envoys from the various fan. However, Wubaochina did not bring any tribute and there is no precedent on which to base rewards.’

The Emperor said:

‘This distant person has come tens of thousands of li from abroad to complain of injustice. How can we not reward him!’

Accordingly, ramie-silk clothing, biao-li of variegated silks, silks and cotton cloth were conferred upon him in the same quantities as those conferred upon tribute envoys from other countries.

Xuande: Year 6, Month 2, Day 7 (20 Mar 1431)

Source: Geoff Wade, translator, Southeast Asia in the Ming Shi-lu: An Open Access Resource, Singapore: Asia Research Institute and the Singapore E-Press, National University of Singapore, http://epress.nus.edu.sg/msl/person/zheng-he, accessed July 02, 2018

“Modern World History Begins in Asia” from Modern World History by Dan Allosso and Tom Williford is licensed CC BY-NC-SA except where otherwise noted.

Updated attribution and licensing edit by Kathy Essmiller, 3.26.23. Contact kathy.essmiller@okstate.edu if corrections are needed or suggested.