7.2 Verbal Elements of Communication

Have you ever said something that someone else misinterpreted as something else? Some of the most common problems in interpersonal communication stem from the use of language. For instance, two students, Kelly and James, are texting each other. Kelly texts James about meeting for dinner, and James texts “K” instead of “okay.” Kelly is worried because she thinks James is mad. She wonders why he texted “K” instead of “k,” “ok,” “yes” or “okay.” James was in a hurry, and he just texted in caps because he was excited to see Kelly.

This example gives us an understanding of how language can influence how our perceptions. Kelly and James had two different perceptions of the same event. One person was worried, and the other person was excited. The words that we use can impact how other people perceive us and how to perceive others.

Language is a system of human communication using a particular form of spoken or written words or other symbols. Language consists of the use of words in a structured way. Language helps us understand others’ wants, needs, and desires. Language can help create connections, but it can also pull us apart. Language is so vital to communication. Imagine if you never learned a language; how would you be able to function? Without language, how could you develop meaningful connections with others? Language allows us to express ourselves and obtain our goals.

Language is the most important element in human communication. Language is made up of words, which are arbitrary symbols. In this chapter, we will learn about how words work, the functions of language, and how to improve verbal communication.

How Words Work

One person might call a shopping cart a buggy, and another person might call it a cart. There are several ways to say you would like a beverage, such as, “liquid refresher,” “soda,” “Coke,” “pop,” “refreshment,” or “drink.” A pacifier for a baby is sometimes called a “paci,” “binkie,” “sookie,” or “mute button.” Linguist Robin Tolmach Lakoff asks, “How can something that is physically just puffs of air, a mere stand-in for reality, have the power to change us and our world?”1 This example illustrates that meanings are in people, and words don’t necessarily represent what they mean.

Words and Meaning

Words can have different rules to help us understand the meaning. There are three rules: semantic, syntactic, and pragmatic.2

Semantic Rules

First, semantic rules are the dictionary definition of the word. However, the meaning can change based on the context in which it is used. For instance, the word fly by itself does not mean anything. It makes more sense if we put the word into a context by saying things like, “There is a fly on the wall;” “I will fly to Dallas tomorrow;” “That girl is so fly;” or “The fly on your pants is open!” We would not be able to communicate with others if we did not have semantic rules.

A cute example of this is about a third-grade teacher who asked about a period. One male student in her class went on and on about how girls have monthly periods, but he did not realize that the teacher meant the use of periods for punctuation at the end of a sentence. Hence, semantic rules need to be understood to avoid embarrassment or misunderstandings.

Syntactic Rules

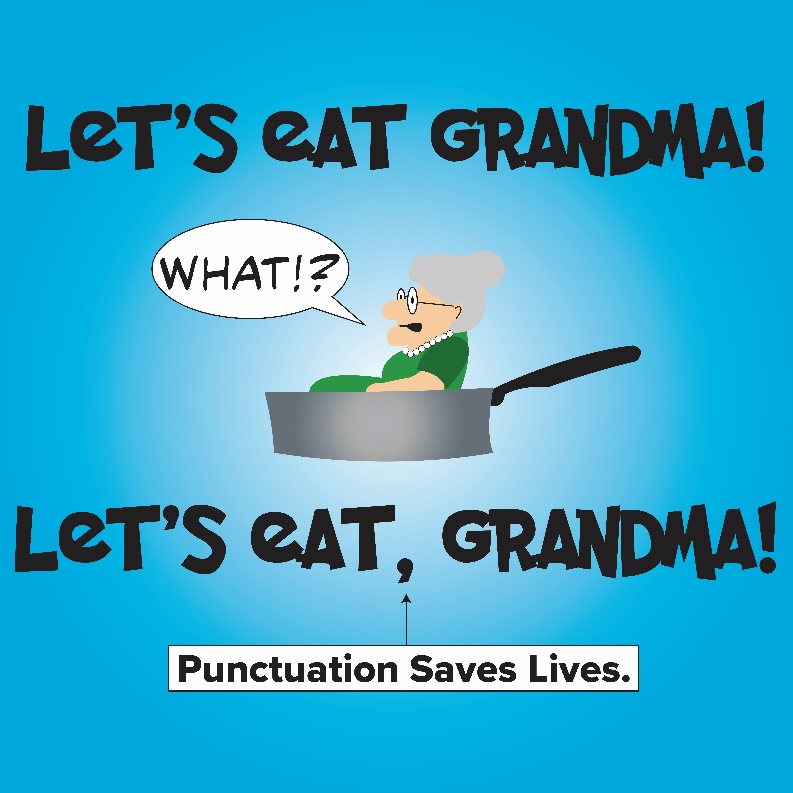

Second, syntactic rules govern how we help guide the words we use. Syntactic rules can refer to the use of grammar, structure, and punctuation to help effectively convey our ideas. For instance, we can say “Where are you” as opposed to “where you are,” which can convey a different meaning and have different perceptions. The same thing can happen when you don’t place a comma in the right place. The comma can make a big difference in how people understand a message.

A great example of how syntactic rules is the Star Wars character, Yoda, who often speaks with different rules. He has said, “Named must be your fear before banish it you can” and “Happens to every guy sometimes this does.” This example illustrates that syntactic rules can vary based on culture or background.

Another example is Figure 4.1. In this case, we learn the importance that a comma can make in written in language. In the first instance, “Let’s eat grandma!” is quite different than the second one, “Let’s eat, grandma!” The first implies cannibalism and the second a family dinner. As the image says, punctuation saves lives.

Figure 7.3

Commas matter

Pragmatic Rules

Third, pragmatic rules help us interpret messages by analyzing the interaction completely. We need to consider the words used, how they are stated, our relationship with the speaker, and the objectives of our communication. For instance, the words “I want to see you now” would mean different things if the speaker was your boss versus your lover. One could be a positive connotation, and another might be a negative one. The same holds true for humor. If we know that the other person understands and appreciates sarcasm, we might be more likely to engage in that behavior and perceive it differently from someone who takes every word literally.

Most pragmatic rules are based on culture and experience. For instance, the term “Netflix and chill” often means that two people will hook up. Imagine someone from a different country who did not know what this meant; they would be shocked if they thought they were going to watch Netflix with the other person and just relax. Another example would be “Want to have a drink?”, which usually infers an alcoholic beverage. Another way of saying this might be to say, “Would you like something to drink?” The second sentence does not imply that the drink has to contain alcohol.

It is common for people to text in capital letters when they are angry or excited. You would interpret the text differently if the text was not in capital letters. For instance, “I love you” might be perceived differently from “I LOVE YOU!!!” Thus, when communicating with others, you should also realize that pragmatic rules can impact the message.

Words Create Reality

Language helps to create reality. Often, humans will label their experiences. For instance, the word “success” has different interpretations depending on your perceptions. Success to you might be a certain type of car or a certain amount of income. However, for someone else, success might be the freedom to do what they love or to travel to exotic places. Success might mean something different based on your background or your culture.

Another example might be the word “intimacy.” Intimacy to one person might be something similar to love, but to another person, it might be the psychological connection that you feel to another person. Words can impact a person’s reality of what they believe and feel.

If a child complains that they don’t feel loved, but the parents/guardians argue that they continuously show affection by giving hugs and doing fun shared activities, who would you believe? The child might say that they never heard their parents/guardians say the word love, and hence, they don’t feel love. So, when we argue that words can create a person’s reality, that is what we mean. Specific words can make a difference in how a person will receive the message. That is why certain rhetoricians and politicians will spend hours looking for the right word to capture the true essence of a message. A personal trainer might be careful to use the word “overweight” as opposed to “fat,” because it just sounds drastically different. At Disney world, they call their employees “cast members” rather than workers, because it gives a perception that each person has a part in helping to run the show. Even on a resume, you might select words that set you apart from the other applicants. For instance, if you were a cook, you might say “culinary artist.” It gives the impression that you weren’t just cooking food, you were making masterpieces with food. Words matter, and how they are used will make a difference.

Words Reflect Attitudes

When we first fall in love with someone, we will use positive adjectives to describe that person. However, if you have fallen out of love with that person, you might use negative or neutral words to describe that same person. Words can reflect attitudes. Some people can label one experience as pleasant and another person can have the opposite experience. This difference is because words reflect our attitudes about things. If a person has positive emotions towards another, they might say that that person is funny, mature, and thrifty. However, if the person has negative feelings or attitudes towards that same person, they might describe them has childish, old, and cheap. These words can give a connotation about how the person perceives them.

Level of Abstraction

When we think of language, it can be pretty. For example, when we say something is “interesting,” it can be positive or negative. That is what we mean when we say that language is abstract. Language can be very specific. You can tell someone specific things to help them better understand what you are trying to say by using specific and concrete examples. For instance, if you say, “You are a jerk!”, the person who receives that message might get pretty angry and wonder why you said that statement. To be clear, it might be better to say something like, “When you slammed that door in my face this morning, it really upset me, and I didn’t think that behavior was appropriate.” The second statement is more descriptive.

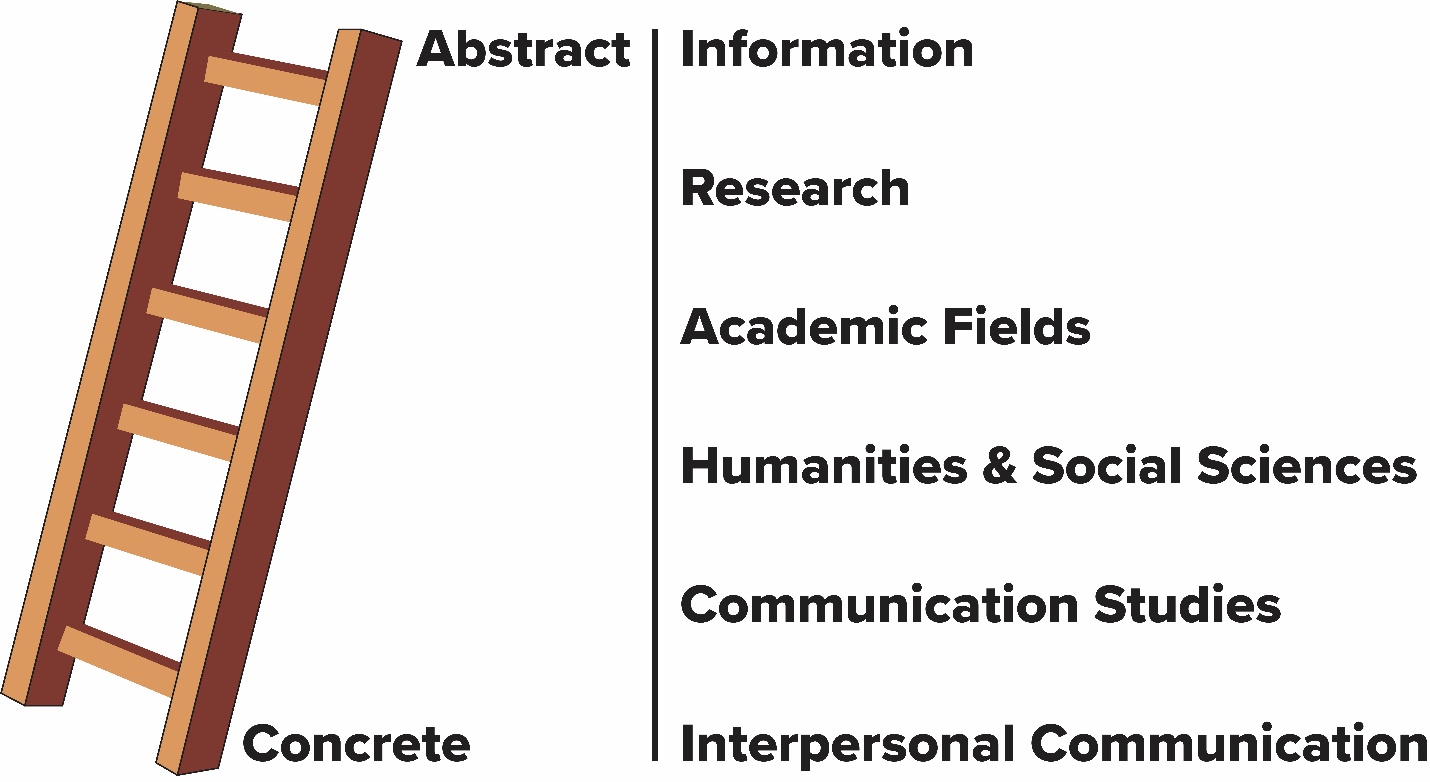

In 1941, linguist S.I. Hayakawa created what is called the abstraction ladder (Figure 4.2).3 The abstraction ladder starts abstract at the top, while the bottom rung and is very concrete. In Figure 4.2, we’ve shown how you can go from abstract ideas (e.g., information) through various levels of more concrete ideas down to the most concrete idea (e.g., interpersonal communication). Ideally, you can see that as we move down the ladder, the topic becomes more fine-tuned and concrete.

In our daily lives, we tend to use high levels of abstraction all the time. For instance, growing up, your parents/guardians probably helped you with homework, cleaning, cooking, and transporting you from one event to another. Yet, we don’t typically say thank you to everything; we might make a general comment, such as a thank you rather than saying, “Thank you so much for helping me with my math homework and helping me figure out how to solve for the volume of spheres.” It takes too long to say that, so people tend to be abstract. However, abstraction can cause problems if you don’t provide enough description.

Figure 7.4

Abstraction Ladder

Metamessages

Metacommunication is known as communication about communication.4 Yet, metamessages are relationship messages that are sent among people who they communicate. These messages can be verbal, nonverbal, direct, or indirect. For instance, if you see two friends just talking about what they did last weekend, they are also sending metamessages as they talk. Metamessages can convey affection, appreciation, disgust, ridicule, scorn, or contempt. Every time you send messages to others, notice the metamessages that they might be sending you. Do they seem upset or annoyed with certain things that you say? In this book, we want to stress the importance of mindfulness when speaking. You may not realize what metamessages you are sending out to others.

Figure 7.5

Perception is key

Words and Meanings

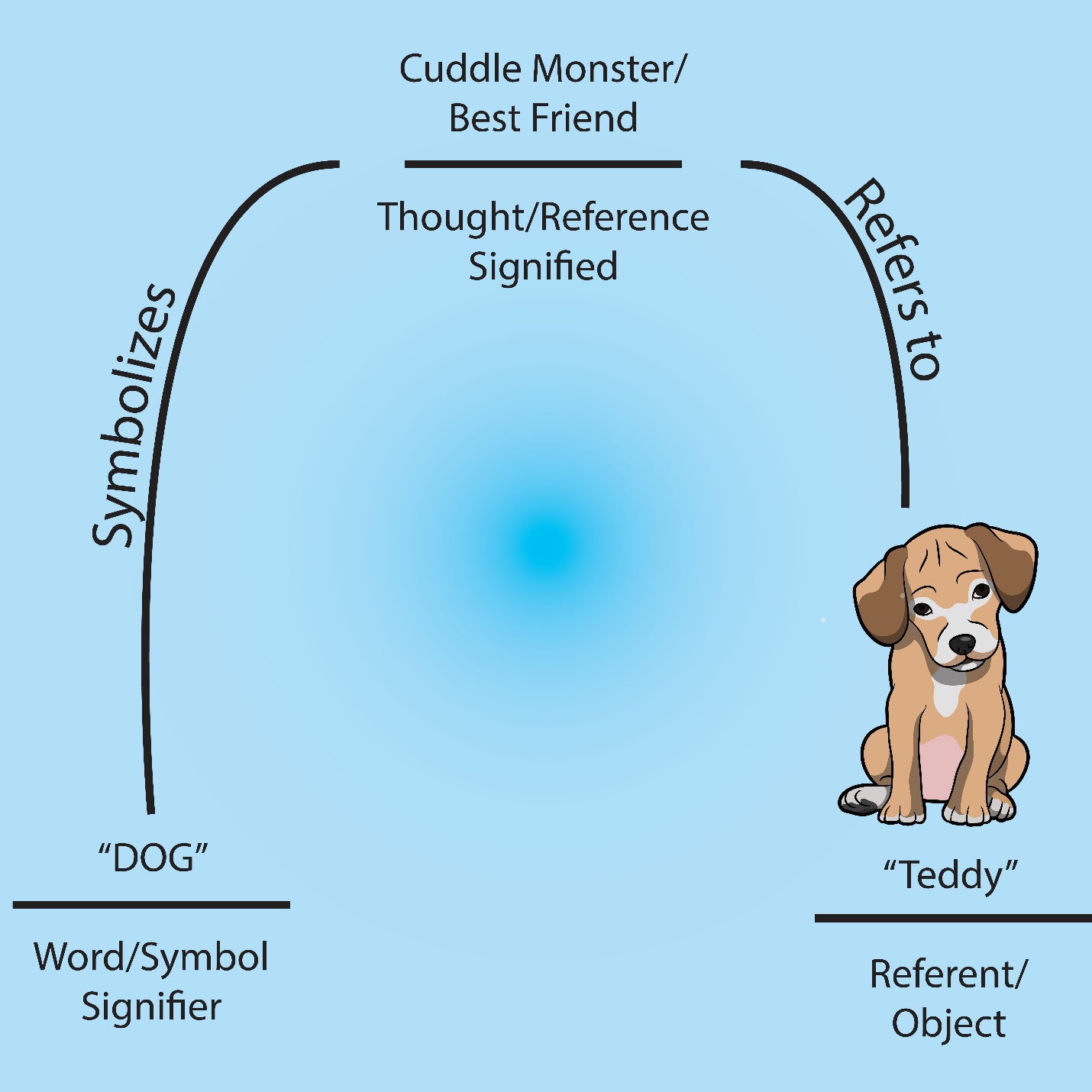

Words can have denotative meanings or connotative meanings. In this section, we will learn about the differences and the triangle of meaning.5 Researchers by the names of Ogden and Richards noticed that misunderstandings occur when people associate different meanings with the same message. Their model (Figure 4.4) illustrates that there is an indirect association between a word and the actual referent or thing it represents.

As you can see, when you hear the word “dog,” it conjures up meaning for different people. The word “dog” itself is a symbol and signifier, or sound elements or other linguistic symbols that represents an underlying concept or meaning. When we hear the word “dog,” it is what we call the “signified,” or the meaning or idea expressed when someone hears the word. In this case, maybe you have a dog, and you really see that dog as your best friend, or, as in my case, you call him your little “cuddle monster” because he always wants to be connected to you at all times. Again, our meaning that we attach to the symbol is still separate from the physical entity itself. In this case, there is a real dog named Teddy, who is the referent, or the physical thing that a word or phrase denotes or stands for.

Figure 7.6

Signifier, Signified, and Referent

Words can have a denotative meaning, which is the dictionary definition. These are words that most people are familiar with, and they all can agree on the understanding of that word. If you asked a person what a car or a phone is, they would most likely know what you are talking about when you use those words.

Words can have a connotative meaning, which is a subjective definition of the word. The word might mean something different from what you meant. For example, you may hear someone referring to their baby. You could fairly safely assume that the person is referring to their infant, but just as easily they could be referring to a significant other.

Key Takeaways

- Words have denotative and connotative meanings. Denotations are the dictionary definition, and connotations are what the words imply.

- Sometimes confusion occurs because people are too abstract in their language. To be clear and concise in language, you need to be descriptive and specific as possible.

- Metamessages involves several meanings and can be conveyed nonverbally and verbally.

Functions of Language

Based on research examining how children learn language, it was found that children are trying to create “meaning potential.”6 In other words, children learn language so they can understand and be understood by others. As children age, language serves different functions.

Instrumental and Regulatory Functions

Children will typically communicate in a fashion that lets parents/guardians know what they want to do. When children are born, parents/guardians have to figure out if the child is hungry, thirsty, dirty, or sick. Later, when the child acquires language, the child can let the parent/guardian know what they want by using simple words like “eat” or “drink.”

Instrumental functions use language to fulfill a need. For us to meet our needs, we need to use language that other people understand.

Language can help us define what we can or cannot do. Often, you might see campaigns that say “Don’t drink and drive” or “Don’t text and drive” to help control behaviors while driving.

Regulatory functions of language are to influence the behaviors of others through requests, rules, or persuasion. These functions do not necessarily coincide with our needs. These might be advertisements that tell us to eat healthier or exercise more using specific products.

Interactional and Imaginative Functions

Interactional functions of language are used to help maintain or develop the relationship. Interactional functions also help to alleviate the interaction. Examples might include “Thank you,” “Please,” or “I care about you.”

Imaginative functions of language help to create imaginary constructs and tell stories. This use of fantasy usually occurs in play or leisure activities. People who roleplay in video games will sometimes engage in imaginative functions to help their character be more effective and persuasive.

Personal Functions

Next, we have personal functions, or the use of language to help you form your identity or sense of self. In job interviews, people are asked, “how do you describe yourself?” For some people, this is a challenging question because it showcases what makes you who you are. The words you pick, as opposed to others, can help define who you are.

Perhaps someone told you that you were funny. You never realized that you were funny until that person told you. Because they used the word “funny” as opposed to “silly” or “crazy,” it caused you to have perceptions about yourself. This example illustrates how words serve as a personal function for us. Personal functions of language are used to express identity, feelings, and options.

Heuristic and Representational Functions

The heuristic function of language is used to learn, discover, and explore. The heuristic function could include asking several questions during a lecture or adding commentary to a child’s behavior. Another example might be “What is that tractor doing?” or “why is the cat sleeping?”

Representational functions of language are used to request or relay information. These statements are straightforward. They do not seek for an explanation. For instance, “my cat is asleep” or “the kitchen light isn’t working.”

Cultural Functions

We know a lot about a culture based on the language that the members of the group speak.7 Some words exist in other languages, but we do not have them in English. For instance, in China, there are five different words for shame, but in the English language, we only have one word for shame. Anthropologist Franz Boas studied the Inuit people of Baffin Island, Canada, in the late 1800s and noted that they had many different words for “snow.” In fact, it’s become a myth over the years that the Inuit have 50 different words for snow. In reality, as Laura Kelly points out, there are a number of Inuit languages, so this myth is problematic because it attempts to generalize to all of them.8 Instead, the Eskimo-Aleut language tends to have long, complicated words that describe ideas; whereas, in English, we’d have a sentence to say the same thing. As such, the Eskimo-Aleut language probably has 100s of different words that can describe snow.

Analyzing the Hopi Native American language, Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf discovered that there is not a difference between nouns and verbs.9 To the Hopi people, their language showcases how their world and perceptions of the world are always in constant flux. The Hopi believe that everything is evolving and changing. Their conceptualization of the world is that there is continuous time. As Whorf wrote, “After a long and careful analysis the Hopi language is seen to contain no words, grammatical forms, construction or expressions that refer directly to what we call ‘time’, or to past, present or future.”10

A very popular theory that helps us understand how culture and language coexist is the Sapir-Worf hypothesis.11 Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf created this hypothesis to help us understand cultural differences in language use. The theory suggests that language impacts perceptions by showing a culture’s worldview. The hypothesis is also seen as linguistic determinism, which is the perspective that language influences our thoughts.

Sometimes, language has special rooted characteristics or linguistic relativity. Language can express not only our thoughts but our feelings as well. Language does not only represent things, but also how we feel about things. For instance, in the United States, most houses will have backyards. In Japan, due to limited space, most houses do not have backyards, and thus, it is not represented in their language. To the Japanese, they do not understand the concept of a backyard, and they don’t have a word for a backyard. All in all, language helps to describe our world and how we understand our world.

Key Takeaways

- Instrumental functions explain that language can help us accomplish tasks, and regulatory function explains that language can help us control behavior.

- Interactional functions help us maintain information, and imaginative functions allow us to create worlds with others.

- When we talk with others, language can be personal, ritual, or cultural. Personal functions help us identify ourselves. Ritual functions of language involve words that we routinely say to others, such as “hello” or “goodbye.” Cultural functions of language help use describe the worldview or perspectives of culture.

The Impact of Language

By now, you can see that language influences how we make sense of the world. In this section, we will understand some of the ways that language can impact our perceptions and possibly our behavior. To be effective communicators, we need to realize the different ways that language can be significant and instrumental.

Naming and Identity

New parents/guardians typically spend a great deal of time trying to pick just the right name for their newborn. We know that names can impact other people’s perceptions.12 Our names impact how we feel and how we behave. For instance, if you heard that someone was named Stacy, you might think that person was female, nice, and friendly, and you would be surprised if that person turned out to be male, mean, and aggressive.

People with unusual names tend to have more emotional distress than those with common names.13 Names impact our identity because others will typically have negative perceptions of unusual names or unique spellings of names. Names can change over time and can gain acceptance. For instance, the name Madison was not even considered a female first name until the movie “Splash” in the 1980s.14

Some names are very distinctive, which also makes them memorable and recognizable. Think about musical artists or celebrities with unique names. It helps you remember them, and it helps you distinguish that person from others.

Some of the names encompass some cultural or ethnic identity. In the popular book, Freakonomics, the authors showed a relationship between names and socioeconomic status.15 They discover that a popular name usually starts with high socioeconomic families, and then it becomes popular with lower socioeconomic families. Hence, it is very conceivable to determine the socioeconomic status of people you associate with based on their birth date and name. Figure 4.5 shows some of the more popular baby names for girls and boys, along with names that are non-binary.

Figure 7.7

Popular Baby Names

Affiliation

When we want others to associate with us or have an affiliation with us, we might change the way we speak and the words we use. All of those things can impact how other people relate to us. Researchers found that when potential romantic partners employed the same word choices regarding pronouns and prepositions, then interest also increased. At the same time, couples that used similar word choices when texting each other significantly increased their relationship duration.16 This study implies that we often inadvertently mimic other people’s use of language when we focus on what they say.

If you have been in a romantic relationship for a long period, you might create special expressions or jargon for the other person, and that specialized vocabulary can create greater closeness and understanding. The same line of thinking occurs for groups in a gang or persons in the military. If we adapt to the other person’s communication style or converge, then we can also impact perceptions of affiliation. Research has shown that people who have similar speech also have more positive feelings for each other.17 However, speech can also work in the opposite direction when we diverge, or when we communicate in a very different fashion. For instance, a group from another culture might speak the same dialect, even though they can speak English, in order to create distance and privacy from others.

Sexism and Racism

Before discussing the concepts of sexism and racism, we must understand the term “bias.” Bias is an attitude that is not objective or balanced, prejudiced, or the use of words that intentionally or unintentionally offend people or express an unfair attitude concerning a person’s race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, age, disability, or illness. We’ll explore more on the issue of biased language later in this chapter.

Sexism or bias against others based on their sex can come across in language. Sexist language can be defined as “words, phrases, and expressions that unnecessarily differentiate between females and males or exclude, trivialize, or diminish either sex.”18 Language can impact how we feel about ourselves and others. For instance, there is a magazine called Working Mother, but there is not one called “Working Father.” Even though the reality is that many men who work also have families and are fathers, there are no words that tend to distinguish them from other working men. Whereas, women are distinguished when they both work and are mothers compared to other women who solely work and also compared to women who are solely mothers and/or wives.

Think about how language has changed over the years. We used to have occupations that were highly male-dominated in the workplace and had words to describe them. For instance, policemen, firemen, and chairmen are now police officers, firefighters, and chairpersons. The same can also be said for some female-dominated occupations. For instance, stewardess, secretary, and waitress have been changed to include males and are often called flight attendants, office assistants, and servers. Thus, to eliminate sexism, we need to be cautious of the word choices we use when talking with others. Sexist language will impact perceptions, and people might be swayed about a person’s capability based on the word choices.

Similarly, racism is the bias people have towards others of a different race. Racist language conveys that a racial group is superior or better than another race. Some words in English have racial connotations. Aaron Smith-McLallen, Blair T. Johnson, John Dovidio, and Adam Pearson wrote:

In the United States and many other cultures, the color white often carries more positive connotations than the color black… Terms such as “Black Monday,” “Black Plague”, “black cats” and the “black market” all have negative connotations, and literature, television, and movies have traditionally portrayed heroes in white and villains in black. The empirical work of John E. Williams and others throughout the 1960s demonstrated that these positive and negative associations with the colors black and white, independent of any explicit connection to race, were evident among Black and White children as young as 3 years old … as well as adults.19

Currently, there is an ongoing debate in the United States about whether President Trump’s use of the phrase “Chinese Virus” when referring to the coronavirus is racially insensitive. The argument for its racial insensitivity is that the President is specifically using the term as an “other” technique to allow his followers to place blame on Chinese people for the coronavirus. Unsurprisingly, as a result of the use of the phase “Chinese Virus,” there have been numerous violent attacks against individuals of Asian descent within the United States. Notice that we don’t say people of Chinese descent here. The people that are generally inflamed by this rhetoric don’t take the time to distinguish among people they label as “other.”

It is important to note that many words do not imply any type of sexual or racial connotations. However, some people might use it to make judgments or expectations of others. For example, when describing a bad learning experience, the student might say “Black professor” or “female student” as opposed to just saying the student and professor argued. These descriptors can be problematic and sometimes not even necessary in the conversation. When using those types of words, it can create slight factors of sexism/racism.

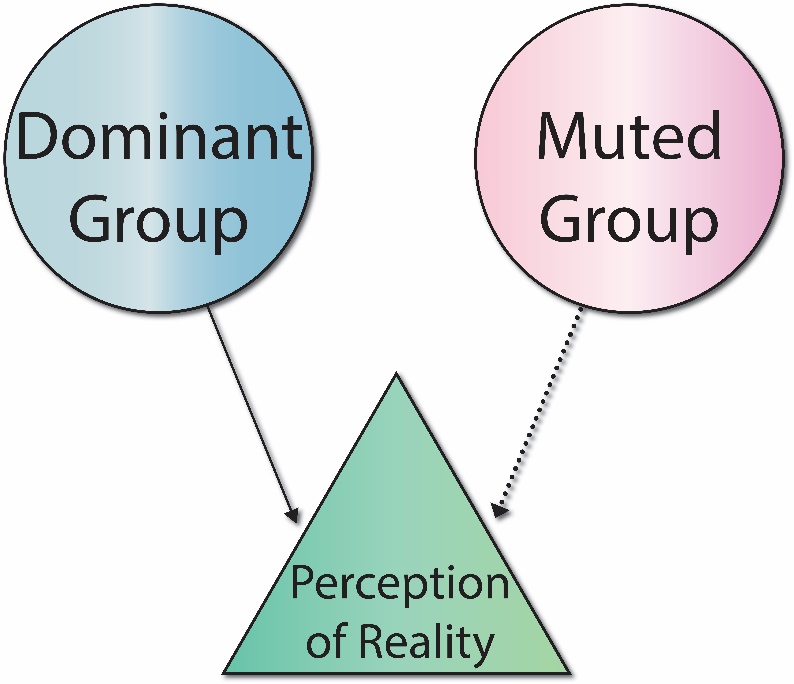

Muted Group Theory

Muted group theory was initially developed to explain the way humans, specifically men and women, communicate.20 The theory claims that man-made communication is, just that, “man”-made. Similar to standpoint theory, muted group theory argues that the dominant members of society, typically men, create a language and system of communication that subverts or reduces other groups, specifically women. Muted group theory has been described as feminist theory, and even this nomenclature is a great example of the claims that the theory is making.21 The term “feminist” exists in a male-dominated culture and language and connotes a negative conception of that which it is used to describe. Even the fact that there is not a popular term used to describe those who fight for the rights and equal status of men, points to the fact that there is a problem. The word “feminist” exists because it deviates from what is perceived as the “norm.” Even the terminology we use to describe women, and a theory that calls attention to their subversion, we see as even more subversion.

Figure 4.6 represents the basic conceptualization of muted group theory. The blue circle represents the dominant group, and the solid arrow points to their perception of reality. Meanwhile, the pink circle represents the muted group, and the dashed line represents their perception of reality. Often what happens in society is that the dominant group’s perception of reality is just seen as reality. As such, the muted group’s perception of reality is seen as less than or more fanciful than the dominant group’s perception. In reality, the muted group often sees things that really do exist in a society that the dominant group either cannot see or chooses not to see based on its position in society as the dominant group.

Figure 7.8

Muted Group Theory

One area in our society where we can examine muted group theory is about socioeconomic status. Here are just a few statements that wealthy people have made:

- When talking about a couple planning their wedding, “I feel sorry for them, because they have a budget.”

- “What do you mean, you don’t know if you should get them? Whenever I want new clothes, I just ask my daddy for the money card.”

- The guy was looking on a website for cars, when a rich coworker asks, “why don’t you just buy the car with cash so you don’t have to make payments?” When the guy told his coworker he couldn’t afford to pay for a car in cash, his rich coworker replied, “Why don’t you just have your parents buy it for you?”

- “If you’re making $50,000 and your salary gets down to $40,000 and you have to cut, it’s very severe to you. But it’s no less severe to these other people with these big numbers.”

- “People who don’t have money don’t understand the stress. Could you imagine what it’s like to say I got three kids in private school, I have to think about pulling them out? How do you do that?”

- “You don’t get the vote if you don’t pay a dollar in taxes. But what I really think is it should be like a corporation. You pay a million dollars, you get a million votes. How’s that?”

The perspectives illustrated in these statements are ones that most of us cannot easily relate to. The opposite is also true. People who live in the top 1% often have very flawed perceptions of what life is like for those who don’t have piles of money sitting around. Often those in the dominant group (in this case the top 1%) have no conceptualization of what life is like for those in muted groups (the bottom 99%). As such, those in muted groups often have a much clearer perception of reality.

Some research in this theory has been done on other subverted groups such as new kids at school.22 They found that it was normative patterns that created a system of subversion in the classroom. When a new student arrived, they inadvertently went against the popular normative habits of the class and, in doing so, ostracized themselves. Other students simultaneously asserted and solidified their dominance while lowering the status of the new student. This same thing can be seen in our male-dominated society. As women seek to make themselves known and heard, they are continually reduced, and male-centric standards are reinforced.

Research Spotlight

Heather Kissack (2010) focused on the subversion and muting of women in email communication within businesses. She found that women are consistently marginalized and muted in organizational emails in the workplace. This is surprising because it would seem that without the nonverbal cues of face-to-face communication, there would be less muting of women in computer-mediated communication. Unfortunately, in this study, one can see that it is the male-centric verbiage that has created this divide in social and organization status. Even as women attempted to un-mute themselves, they were increasingly muted and subverted.

Heather Kissack (2010) focused on the subversion and muting of women in email communication within businesses. She found that women are consistently marginalized and muted in organizational emails in the workplace. This is surprising because it would seem that without the nonverbal cues of face-to-face communication, there would be less muting of women in computer-mediated communication. Unfortunately, in this study, one can see that it is the male-centric verbiage that has created this divide in social and organization status. Even as women attempted to un-mute themselves, they were increasingly muted and subverted.

Kissack, H. (2010). Muted voices: a critical look at e-male in organizations. Journal of European Industrial Training, 34(6), 539-551. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090591011061211

Key Takeaways

- Names can impact how we perceive others. It can also impact how we feel about ourselves.

- We can increase affiliation with others through converging our language to others. We can decrease affiliation with others through diverging our language with others.

- Sexism and racism can be displayed through our language choices. It is important to be aware of the words we use so that we do not come across as sexist or racist.

Types of Language

If you read or watch different types of programming, you will probably notice that there is a difference in language use based on the environment, who you are talking to, and the reason for communicating. In this section, we will discuss the different types of language. The types of language used will impact how others view you and if they will view you positively or negatively.

Formal vs. Informal Language

You probably know by now that how we communicate in different contexts can vary greatly. For example, how you compose a text to your best friend is going to use different grammatical structures and words than when you compose an email to your professor. One of the main reasons for this difference is because of formal and informal language. Table 7.1 provides a general overview of the major differences between formal and informal language.

Table 7.1

Formal vs. Informal Language

| Formal Language | Informal Language |

|---|---|

| Used in carefully edited communication. | Used in impromptu, conversational communication. |

| Used in academic or official content. | Used in everyday communication. |

| The sentence structure is long and complicated. | The sentence structure is short, choppy, and improvised. |

| The emphasis is on grammatical correctness. | The emphasis is on easily understood messages using everyday phrases. |

| Uses the passive voice. | Uses the active voice. |

| Often communicated from a detached, third person perspective. | Perspective is less of a problem (1st, 2nd or 3rd). |

| Speakers/writers avoid the use of contractions. | Speakers/writers can actively include contractions. |

| Avoid the inclusion of emotionally laden ideas and words. | It allows for the inclusion of emotions and empathy. |

| Language should be objective. | Language can be subjective. |

| Language should avoid the use of colloquialisms. | It’s perfectly appropriate to use colloquialisms. |

| Only use an acronym after it has clearly been spelled out once. | People use acronyms without always clearly spelling out what it means. |

| All sentences should be complete (clear subjects and verbs). | Sentences may be incomplete (lacking a clear subject and/or verb). |

| The use of pronouns should be avoided. | The use of personal pronouns is common. |

| Avoids artistic languages as much as possible. | Includes a range of artistic language choices (e.g., alliteration, anaphora, hyperbole, onomatopoeia, etc.). |

| Arguments are supported by facts and documented research. | Arguments are supported by personal beliefs and opinions. |

| Language is gender neutral. | Language includes gender references. |

| Avoids the imperative voice. | Uses the imperative voice. |

Formal Language

When applying for a job, you will most likely use formal language in your cover letter and resume. Formal language is official and academic language. You want to appear intelligent and capable, so formal language helps you accomplish those goals. Formal language often occurs when we write. Formal language uses full sentences and is grammatically correct. Formal language is more objective and more complex. Most legal agreements are written in formal language.

Informal Language

Informal language is common, everyday language, which might include slang words. It is continuous and casual. We use informal language when we talk to other people. It is more simple. Informal language tends to use more contractions and abbreviations. If you look at your text messages, you will probably see several examples of informal language.

Jargon

Jargon is the specialized or technical language of a specific group or profession that may not be understood by outsiders.23 If you are really into cars or computers, you probably know a lot about the different parts and functions. Jargon is normally used in a specific context and may be understood outside that context. Jargon consists of a specific vocabulary that uses words that only certain people understand. The business world is full of jargon. Joanna Cutrara created a list of 14 commonly heard jargon phrases used in the business world:24

- Low Hanging Fruit

- Leverage

- Open the Kimono

- Giving 110%

- Out of Pocket

- Drink the Kool-Aid

- Bio Break

- Blue Sky Training

- Tiger Team

- Idea Shower or Thought Shower

- Moving the Goal Post

- Drill Down

- Gain Traction

If you’re like us, chances are you’ve heard a few of these jargon phrases in your workplace. Heck, you may have even found yourself using a few of them. Your workplace may even have some specific jargon only used in your organization. Take a minute and think through all of the jargon you hear on an average day.

Colloquialisms

Colloquialisms are the use of informal words in communication.25 Colloquialism varies from region to region. Examples might be “wanna” instead of “want to” or “gonna” instead of “going to.” It shows us how a society uses language in their everyday lives. Here’s a short list of some common colloquialisms you may have used yourself:

- Bamboozle – to deceive

- Be blue – to be sad

- Beat around the bush – to avoid a specific topic

- Buzz off – go away

- Fell through the cracks – to be neglected

- Go bananas, or go nuts – go insane or be very angry

- Gobsmacked – shocked

- Gonna – going to

- Hit a writer’s block – unable to write

- Hit the hay – to go to sleep

- Pop into my head – to have a new thought

- Sticktoitiveness – to be persistent

- Threw me for a loop – to be surprised

- Throw someone under the bus – to throw the blame on another person

- Wanna – want to

- Y’all – you all

- Yinz – you all

Slang

Slang refers to words that are employed by certain groups, such as young adults and teens.26 Slang is more common when speaking to others rather than written. Slang is often used with people who are similar and have experience with each other. Here is a list of some common slang terms you may use in your day-to-day life:

- BAE (baby / before all else)

- On Fleek (looking perfect)

- Bye Felica (saying goodbye to someone you don’t like)

- The Tea (gossip)

- Bro (typically a male friend)

- Cash (money)

- Cheesy (cheap or tacky)

- Ship (wanting people to be in a relationship, whether real or fictional)

- Frenemy (someone who is both a friend and an enemy)

- Thirsty (being overly eager or desperate)

- Throw Shade (to insult another person)

- Woke (being acutely aware of social injustice within society)

How many of these slang words do you use? What other slang words do you find yourself using? When it comes to slang, it’s important to understand that this list is constantly evolving. What is common slang today could be completely passé tomorrow. What’s common slang in the United States is not universal in English speaking countries.

Idioms

Idioms are expressions or figures of speech whose meaning cannot be understood by looking at the individual words and interpreting them literally.27 Idioms can help amplify messages. Idioms can be used to provide artistic expression. For instance, “knowledge is power!”

Idioms can be hard to grasp for non-native speakers. As such, many instructors in the English as a Second Language world spend a good deal of time trying to explain idioms to non-native speakers. Table 7.2 presents a wide array of different idioms.

Table 7.2

Common Idioms

| Reused here from Kifissia under a Creative Commons Attribution License. https://tinyurl.com/rtxklo5 | |

| IDIOM | MEANING/SENTENCE |

|---|---|

| ish | About. I’ll meet you at 4ish. |

| a basket case | A wreck. He was a basket case after he was thrown off the basketball team. |

| a breath of fresh air | Refreshing/fun. She’s a breath of fresh air. |

| a change of heart | Change my mind. I’ve had a change of heart. |

| a blessing in disguise | Something bad that turns out good. Losing his job turned out to be a blessing in disguise. |

| a dead end | That’s a dead end job–time to find a new one. |

| a gut feeling | Feeling in my stomach. I have a gut feeling that everything is going to turn out all right. |

| a matter of opinion | It’s a matter of opinion whether eating fried tarantulas is a gourmet treat. |

| a piece of cake | That test was a snap–it was a piece of cake. (easy). |

| a ripoff | You spent $500 for a watermelon! What a ripoff! You were cheated. |

| a pain in the neck | A pest. His little brother is a real pain in the neck. |

| be in hot water | Be in trouble. If you tell your boss off, you’ll really be in hot water. |

| in the same boat | We’re in the same situation. We’re all in the same boat–so be cool. |

| on the same wavelength | We have the same ideas and opinions. We’re on the same wavelength. |

| be on the ball | Very sharp. Very smart. He’s really on the ball. |

| it’s only a matter of time | Very soon. It’s only a matter of time until his boss realizes that he is the one stealing money from the till. |

| be that as it may | As things stand. Be that as it may, I think you should reconsider your decision to move to Antarctica. |

| up in arms | Really angry. His father was up in arms when he learned that he had crashed his new car. |

| up in the air | Not sure. Plans are up in the air–we haven’t decided what to do yet. |

| bend over backwards | Go out of your way. She really bent over backwards to make my stay enjoyable. |

| Big deal! | Not important (sarcastic). Losing an old sock is not a big deal. |

| cost an arm and a leg | Very expensive. His new Ferrari cost an arm and a leg. |

| cross your fingers | For good luck. Cross your fingers that I pass the English exam with flying colors. |

| draw a blank | I can’t remember. I drew a blank when I tried to remember his brother’s name. |

| Easier said than done | More difficult than it seems. |

| Am fed up with | Sick and tired of something. I’m fed up with whining friends who have everything! |

| from scratch | Make from basic ingredients. Her carrot cake was made from scratch. |

| for the time being | For now. For the time being, everything is fine at work. |

| get cold feet | Feel too scared to do something. John wanted to ask Maria out but he got cold feet and decided not to. |

| get out of the wrong side of the bed | In a bad mood. He must have gotten up out of the wrong side of the bed today. |

| get the picture | Understand. Do you get the picture? |

| get your act together | Get organized/stop wasting time. You better get your act together or you’re going to fail all your classes. |

| give it a shot | Try. Why not try bungee jumping. Give it a shot. |

| give him a piece of your mind | Get angry and tell someone off. If I were you I would give him a piece of your mind. |

| give him the cold shoulder | Ignore someone. Brett walked right past me without saying a word. He gave me the cold shoulder. |

| go all out | Do your utmost for someone or something. His parents went all out for his graduation party. |

| go downhill | Get worse. After he got divorced, everything went downhill. |

| go up in smoke | Evaporate/disappear. His dreams of being a professional athlete went up in smoke when he broke his leg. |

| have a chip on your shoulder | I think you are great. He has such a chip on his shoulder that he hardly ever relates to anyone. |

| had it up to here | Can’t take any more. I’ve had it up to here with noisy students! |

| mixed feelings | Positive and negative feelings together. I have very mixed feelings about her marrying a fisherman. |

| second thoughts | Thinking again about a decision. I’m having second thoughts about trekking in Greenland this summer. |

| throw a fit | Get really angry. His mother threw a fit when she heard that he lost her iPhone. |

| I’m all ears | To listen intently. Tell me about your wedding plans–I’m all ears. |

| in the bag | Certain. His new job is in the bag. He signed the contract. |

| in the middle of nowhere | Way out in the country. Their ski chalet is in the middle of nowhere. |

| Just my luck! | Bad luck. Just my luck to lose the winning lottery ticket. |

| keep an eye on | Watch carefully. Will you keep an eye on my nephew while I walk the dog? |

| bear in mind | Keep it in mind. Bear in mind, learning a new language isn’t as easy as it seems. |

| learn by heart | Memorize. You have to learn irregular verbs by heart. |

| let the cat out of the bag | Spill the beans. Tell a secret. Don’t let the cat out of the bag. Keep his surprise birthday party a secret. |

| make my day | Make my day great. The guy I have a crush on finally called me. He made my day. |

| miss the point | Don’t understand the basic meaning. You are missing the point entirely.-. |

| no way | Impossible. You got all A’s on your exams and you never studied. No way! |

| don’t have a clue | I have no idea. I don’t have a clue what the professor was talking about. |

| don’t have the faintest idea | Don’t understand. I don’t have the faintest idea of what that article was talking about. |

| off the top of my head | Without thinking. Off the top of my head, I think it’s worth $6 million. |

| on the dot | Ontime. He arrived at 6 o’clock on the dot. |

| out of sight, out of mind | You forget someone you don’t see anymore. |

| out of the blue | Suddenly. Guess who called me out of the blue? |

| play it by ear | Make no plans–do things spontaneously. Let’s just play it by ear tonight and see what comes up. |

| pull someone’s leg | Kid someone. Stop pulling my leg. I know you are kidding! |

| red tape | Bureaucracy. It’s almost impossible to set up a business in Greece because there is so much red tape. |

| read between the lines | Understand what is not stated. If you read between the lines, you’ll realize that he is trying to dump you. |

| safe and sound | Fine. The Boy Scouts returned safe and sound from their camping adventure in Yellowstone National Park. |

| see eye to eye | Agree. He doesn’t see eye to eye with his parents at all. |

| sour grapes | Pretend to not want something that you are desperate for. It’s just sour grapes that he is criticizing George’s villa in Italy. |

| slipped my mind | Forgot. I meant to call you last night, but it slipped my mind. |

| small talk | Chitchat. It’s important to be able to make small talk when you meet new people for the first time. |

| talk shop | Talk about work. What a boring evening! Everyone talked shop- and they’re all dog walkers! |

| the icing on the cake | Something that makes a good thing great. And the icing on the cake was that the movie for which he earned $12 million, also won the Oscar for best picture. |

| the last straw | The thing that ruins everything. When my boss asked me to cancel my wedding to complete a project–I said that’s the last straw and I quit! |

| time flies | Time goes fast. Time flies when you are having fun. |

| you can say that again | You agree emphatically. Kanye West is a great singer. You can say that again! |

| you name it | Everything you can think of. This camp has every activity you can think it–like swimming, canoeing, basketball and you name it. |

| wouldn’t be caught dead | Not even dead would I do something. I wouldn’t be caught dead wearing that dress to the ball. |

| she’s a doll | Someone really great. Thanks for helping me out. You’re a doll. |

| full of beans | Lively–usually for a child. Little children are usually full of beans. |

| full of baloney | Not true. She’s full of baloney–she doesn’t know what she is talking about. |

| like two peas in a pod | Very similar. His two brothers are like peas in a pod. |

| a piece of cake | Very easy. My math test was so easy–a real piece of cake. |

| sounds fishy | Suspicious. Doubling your money in an hour sounds fishy to me. |

| a frog in my throat | I can’t speak clearly. Ahem! Sorry I had a frog in my throat. |

| smell a rat | Something is suspicious. The policeman didn’t believe the witness–in fact, he smelled a rat. |

| go to the dogs | Go downhill. Everything is going to the dogs in our town since the new mayor took office. |

| cat got your tongue | Silent for no reason. What’s the matter? Cat got your tongue? |

| for the birds | Awful. How was the new Batman movie? Oh, it was for the birds. |

| pay through the nose | Pay lots of money. They paid through the nose to hold their wedding at Buckingham Palace. |

| tongue in cheek | Being ironic. I meant that tongue in cheek. I was kidding. |

| all thumbs | Clumsy. He couldn’t put that simple table together–he’s just all thumbs. |

| get off my back | Leave me alone. Bug off! Get off my back! |

| drive me up a wall | Drive me crazy. Rude people drive me up a wall. |

| spill the beans | Tell a secret. Hey, don’t spill the beans. It’s a secret. |

| hit the ceiling | Blow up. His dad hit the ceiling when he saw his dreadful report card. |

| go fly a kite | Get lost! Oh, leave me alone! Go fly a kite! |

| dressed to kill | Dressed in fancy clothes. Cinderella was dressed to kill when she arrived at the ball. |

| in stitches | Laughing a lot. We were all in stitches when we heard the latest joke. |

| feel like a million dollars | Feel great. I just slept for 15 hours–I feel like a million dollars. |

| at the end of my rope | Can’t stand it anymore. The mother of four little children is at the end of her rope. |

| my head is killing me | Something hurts. My head is killing me–I should take an aspirin. |

| that’s out of the question | Impossible. Me? Stand up and sing and dance in front of the whole school–out of the question! |

| I’m beat | Very tired. |

| It’ll knock your socks off! | Thrills you. You’ll love this summer’s action movie. It’ll knock your socks off. |

| beats me | Don’t know. What’s the capital of Outer Mongolia? Beats me! |

| hands down | No comparison. Hands down Mykonos is the world’s most beautiful island. |

| goody-goody | Behaves perfectly. I can’t stand Matilda–she’s such a goody-goody and no fun at all. |

| pain in the neck | A big problem. Washing dishes is a pain in the neck. |

| like pulling teeth | Very difficult. Trying to get 2-year-olds to cooperate is like pulling teeth. |

| for crying out loud | Oh no! For crying out loud–let me finish this book–will you? |

| I’m at my wit’s end | I’m desperate. I’m at my wit’s end trying to deal with two impossible bosses. |

| like beating a dead horse | A waste of time. Trying to get my father to ever change his mind is like beating a dead horse. |

| out of this world | Fantastic! My vacation to Hawaii was out of this world! |

| cost an arm and a leg | Very expensive. A Rolls Royce costs an arm and a leg. |

| go figure | Try to guess why. Our English teacher gives us five tests a week and this week–no tests at all. Go figure. |

| in the nick of time | Just in time. The hero arrived in the nick of time to save the desperate damsel. |

| I’m up to my eyeballs in | Very busy. I’m up to my eyeballs in work this week. |

| I had a blast/a ball | A great time. I had a blast/ball at Sandy’s slumber party. |

| win-win situation | Both sides win. Selling their old stock of iPhones 10s was a win-win situation. They got rid of the useless phones, and we bought them really cheaply. |

| I’m swamped | Very busy. Let’s get together next week–this week I’m swamped. |

| It’s a steal | Fantastic bargain. Getting a new computer for $300 dollars is a steal. |

| the sticks | Way out in the country. Who would want to live in the sticks–what would you do for excitement? |

| break the ice | Start a conversation. Talking about the weather is a good way to break the ice when you meet someone new. |

| give me a break | Leave me alone! Come on! Give me a break! I’ve been working all day long- and I just want to play a little bit of Angry Birds…. |

| like talking to the wall | A waste of time. Dealing with many teenagers is like talking to a wall–they won’t even respond to your questions. |

| see eye to eye | Agree. I hardly ever see eye to eye with my parents. |

| It’s about time | It’s time. It’s about time you started your homework–it’s midnight! |

| pays peanuts | Pays hardly anything. This job pays peanuts–$1 an hour!. |

| sleep like a log | Sleep soundly. Last night I slept like a log and didn’t hear the thunderstorm at all. |

| ace | Do great. I aced the math test. I got 100%. |

| easy as pie | Super easy. The English test was as easy as pie. |

| blabbermouth | Someone who tells secrets. Don’t tell Sophie your secrets or the whole town will know them. |

| don’t bug me | Don’t bother me. Don’t bug me–I’m busy. |

| by the skin of my teeth | Barely manage something. I passed the geography test by the skin of my teeth. |

| can’t make head nor tail of | I can’t understand. I can’t make head nor tail of this math chapter. |

| cool as a cucumber | Very calm. The policeman was cool as a cucumber when he persuaded the man not to jump off the Brooklyn Bridge. |

Clichés

Cliché is an idea or expression that has been so overused that it has lost its original meaning.28 Clichés are common and can often be heard. For instance, “light as a feather” or “happily ever after” are common clichés. They are important because they express ideas and thoughts that are popular in everyday use. They are prevalent in advertisements, television, and literature.

Improper Language

Improper language is not proper, correct, or applicable in certain situations.29 There are two different types of improper language: vulgarity and cursing. First, vulgarity includes language that is offensive or lacks good taste. Often, vulgar is lewd or obscene. Second, cursing is language that includes evil, doom, misfortune on a person or group. It can also include curse or profane words. People might differ in their perceptions about improper language.

Biased Language

Biased language is language that shows preference in favor of or against a certain point-of-view, shows prejudice, or is demeaning to others.30 Bias in language is uneven or unbalanced. Examples of this may include “mankind” as opposed to “humanity.”

Table 7.3

Biased Language

| Avoid | Consider Using |

|---|---|

| Black Attorney | Attorney |

| Businessman | Businessperson, Business Owner, Executive, Leader, Manager, etc. |

| Chairman | Chair or Chairperson |

| Cleaning Lady / Maid | Cleaner, Cleaning Person, Housecleaner, Housekeeper, Maintenance Worker, Office Cleaner, etc. |

| Male Nurse | Nurse |

| Male Flight Attendant or Stewardess | Flight Attendant |

| Female Doctor | Physician or Doctor |

| Manpower | Personnel or Staff |

| Congressman | Legislator, Member of Congress, or Member of the House of Representatives |

| Postman | Postal Employee or Letter carrier |

| Forefather | Ancestor |

| Policeman | Police Officer / Law Enforcement Officer |

| Fireman | Firefighter |

| Disabled | People with Disabilities |

| Schizophrenic | Person Diagnosed with Schizophrenia |

| Homosexual | Lesbians, Gay Men, Bisexual Men or Women |

One specific type of biased language is called spin, or the manipulation of language to achieve the most positive interpretation of words, to gain political advantage, or to deceive others. In essence, people utilizing spin can make language choices that frame themselves or their clients in a positive way.

Ambiguous Language

Ambiguous language is language that can have various meanings. Google Jay Leno’s headlines videos. Sometimes he uses advertisements that are very abstract. For instance, there is a restaurant ad that says, “People are our best ingredient!” What comes to mind when you hear that? Are they actually using people in their food? Or do they mean their customer service is what makes their restaurant notable? When we are trying to communicate with others, it is important that we are clear in our language. We need others to know exactly what we mean and not imply meaning. That is why you need to make sure that you don’t use ambiguous language.

Euphemisms

Euphemisms also make language unclear. People use euphemisms as a means of saying something more politely or less bluntly. For instance, instead of telling your parents/guardians that you failed a test, you might say that you did sub-optimal. People use euphemisms because it sounds better, and it seems like a better way to express how they feel. People use euphemisms all the time. For instance, instead of saying this person died, they might say the person passed away. Instead of saying that someone farted, you might say someone passed gas.

Relative Language

Relative language depends on the person communicating. People’s backgrounds vary. Hence, their perspectives will vary. I know a college professor that complains about her salary. However, other college professors would love to have a salary like hers. In other words, our language is based on our perception of our experiences. For instance, if someone asked you what would be your ideal salary, would it be based on your previous salary? Your parents? Your friends? Language is relative because of that reason. If I said, “Let’s go eat at an expensive restaurant,” what would be expensive for you? For some person, it would be $50, for another, $20, for someone else it might be $10, and yet there might be someone who would say $5 is expensive!

Static Evaluation

Often times, we think that people and things do not change, but they do change. If you ever watch afternoon talk shows, you might see people who go through amazing transformations, perhaps through weight loss, a makeover, or surgery or some sort. These people changed. Static evaluation states that things are not constant. Things vary over time, and our language should be representative of that change. For instance, Max is bad. It is important to note that Max might be bad at one time or may have displayed bad behavior, but it may not represent how Max will be in the future.

Mindfulness Activity

For the entire day, we want you to take a minute to pause before you text or email someone. When we text or email someone, we typically just put our thoughts together in a quick fashion. Take a second to decide how you plan to use your words. Think about which words would be best to get our message across effectively. After you have typed your message, take another few minutes to reread the message. Be mindful of how others might interpret your message. Would they read it at face value, or would they misinterpret the message because there is a lack of nonverbal messages? Do you need to add emojis or GIFS to change how the message is conveyed?

For the entire day, we want you to take a minute to pause before you text or email someone. When we text or email someone, we typically just put our thoughts together in a quick fashion. Take a second to decide how you plan to use your words. Think about which words would be best to get our message across effectively. After you have typed your message, take another few minutes to reread the message. Be mindful of how others might interpret your message. Would they read it at face value, or would they misinterpret the message because there is a lack of nonverbal messages? Do you need to add emojis or GIFS to change how the message is conveyed?

Researchers have found that when college students can address their emotions and are mindful of their feelings, it can enhance written communication with others.31 After doing this activity, try to be more mindful of the things that you send to other people.

Key Takeaways

- Formal language is more careful and more mannered than everyday speech, whereas informal language is appropriate in casual conversation.

- Informal language includes (1) Jargon, or technical language; (2) Colloquialism, or informal expressions; (3) Slang, or nonstandard language; (4) Idioms, or expressions or figures of speech; (5) clichés, or sayings that are overused and predictable.

Chapter Wrap-Up

In this chapter, we discussed the importance of verbal communication. To be an effective verbal communicator, it is necessary to understand that the words you use convey meanings that you might intentionally or unintentionally communicate to others. However, the meaning of language can vary from person to person.

This chapter also discusses the various rules of language. Verbal communication serves many purposes and works to clarify the meaning of nonverbal communication. The type of language that you use can impact how others will see you.

Finally, this chapter discusses the subcategories of verbal communication. The subcategories of verbal communication allow us to understand how misunderstandings might occur if language is not used effectively.

Notes

People create systems that reflect cultural values. These systems reduce uncertainty for the culture, creating and perpetuating the rules and customs, but may prove a significant challenge to the entrepreneur entering a new market. Political, legal, economic, and ethical systems vary from culture to culture, and may or may not reflect formal boundaries. For example, disputes over who controls what part of their shoreline are common and are still a matter of debate, interpretation, and negotiation in many countries.

To a large extent, a country’s culture is composed of formal systems. Formal systems often direct, guide, constrain, or promote some behaviors over others. A legal system, like taxation, may favor the first-time homebuyer in the United States, and as a consequence, home ownership may be pursued instead of other investment strategies. That same legal system, via tariffs, may levy import taxes on specific goods and services, and reduce their demand as the cost increases. Each of these systems reinforces or discourages actions based on cultural norms, creating regulations that reflect ways that each culture, through its constituents, views the world.

In this section, we’ll examine intercultural communication from the standpoint of international communication. International communication can be defined as communication between nations, but we recognize that nations do not exist independent of people. International communication is typically government to government or, more accurately, governmental representatives to governmental representatives. It often involves topics and issues that relate to the nations as entities, broad issues of trade, and conflict resolution. People use political, legal, and economic systems to guide and regulate behavior, and diverse cultural viewpoints necessarily give rise to many variations. Ethical systems also guide behavior, but often in less formal, institutional ways. Together these areas form much of the basis of international communication, and warrant closer examination.

Political Systems

You may be familiar with democracy, or rule by the people; and theocracy, or rule of God by his or her designates; but the world presents a diverse range of how people are governed. It is also important to note, as we examine political systems, that they are created, maintained, and changed by people. Just as people change over time, so do all systems that humans create. A political climate that was once closed to market forces, including direct and indirect investment, may change over time.

Centuries ago, China built a physical wall to keep out invaders. In the twentieth century, it erected another kind of wall: a political wall that separated the country from the Western world and limited entrepreneurship due to its adherence to its interpretation of communism. In 2009, that closed market is now open for business. To what extent it is open may be a point of debate, but simple observation provides ample evidence of a country, and a culture, open to investment and trade. The opening and closing ceremonies for the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing symbolized this openness, with symbolic representations of culture combined with notable emphasis on welcoming the world. As the nature of global trade and change transforms business, so it also transforms political systems.

Political systems are often framed in terms of how people are governed, and the extent to which they may participate. Democracy is one form of government that promotes the involvement of the individual, but even here we can observe stark differences. In the United States, people are encouraged to vote, but it is not mandatory, and voter turnout is often so low that voting minorities have great influence on the larger political systems. In Chile, voting is mandatory, so that all individuals are expected to participate, with adverse consequences if they do not. This doesn’t mean there are not still voting minorities or groups with disproportionate levels of influence and power, but it does underscore cultural values and their many representations.

Centralized rule of the people also comes in many forms. In a dictatorship, the dictator establishes and enforces the rules with few checks and balances, if any. In a totalitarian system, one party makes the rules. The Communist states of the twentieth century (although egalitarian in theory) were ruled in practice by a small central committee. In a theocracy, one religion makes the rules based on their primary documents or interpretation of them, and religious leaders hold positions of political power. In each case, political power is centralized to a small group over the many.

A third type of political system is anarchy, in which there is no government. A few places in the world, notably Somalia, may be said to exist in a state of anarchy. But even in a state of anarchy, the lack of a central government means that local warlords, elders, and others exercise a certain amount of political, military, and economic power. The lack of an established governing system itself creates the need for informal power structures that regulate behavior and conduct, set and promote ideals, and engage in commerce and trade, even if that engagement involves nonstandard strategies such as the appropriation of ships via piracy. In the absence of appointed or elected leaders, emergent leaders will rise as people attempt to meet their basic needs.

Legal Systems

Legal systems also vary across the planet and come in many forms. Some legal systems promote the rule of law while others promote the rule of culture, including customs, traditions, and religions. The two most common systems are civil and common law. Civil law draws from a Roman history and common law from an English tradition. In civil law the rules are spelled out in detail, and judges are responsible for applying the law to the given case. In common law, the judge interprets the law and considers the concept of precedent, or previous decisions. Common law naturally adapts to changes in technology and modern contexts as precedents accumulate, while civil law requires new rules to be written out to reflect the new context even as the context transforms and changes. Civil law is more predictable and is practiced in the majority of countries, while common law involves more interpretation that can produce conflict with multiple views on the application of the law in question. The third type of law draws its rules from a theological base rooted in religion. This system presents unique challenges to the outsider, and warrants thorough research.

Economic Systems

Economic systems vary in similar ways across cultures, and again reflect the norms and customs of people. Economies are often described on the relationship between people and their government. An economy with a high degree of government intervention may prove challenging for both internal and external businesses. An economy with relatively little government oversight may be said to reflect more of the market(s) and to be less restricted. Along these same lines, government may perceive its role as a representative of the common good, to protect individual consumers, and to prevent fraud and exploitation.

This continuum or range, from high to low degrees of government involvement, reflects the concept of government itself. A government may be designed to give everyone access to the market, with little supervision, in the hope that people will regulate transactions based on their own needs, wants, and desires; in essence, their own self-interest. If everyone operates in one’s self-interest and word gets out that one business produces a product that fails to work as advertised, it is often believed that the market will naturally gravitate away from this faulty product to a competing product that works properly. Individual consumers, however, may have a hard time knowing which product to have faith in and may look to government to provide that measure of safety.

Government certification of food, for example, attempts to reduce disease. Meat from unknown sources would lack the seal of certification, alerting the consumer to evaluate the product closely or choose another product. In terms of supervision, we can see an example of this when Japan restricts the sale of U.S. beef for fear of mad cow disease. The concern may be warranted from the consumer’s viewpoint, or it may be protectionist from a business standpoint, protecting the local producer over the importer.

From meat to financial products, we can see both the dangers and positive attributes of intervention and can also acknowledge that its application may be less than consistent. Some cultures that value the community may naturally look to their government for leadership in economic areas, while those that represent an individualistic tendency may take a more “hands off” approach.

Ethical Systems

Ethical systems, unlike political, legal, and economic systems, are generally not formally institutionalized. This does not imply, however, that they are less influential in interactions, trade, and commerce. Ethics refers to a set of norms and principles that relate to individual and group behavior, including businesses and organizations. They may be explicit, in the form of an organization’s code of conduct; may be represented in religion, as in the Ten Commandments; or may reflect cultural values in law. What is legal and what is ethical are at times quite distinct.

For example, the question of executive bonuses was hotly debated when several U.S. financial services companies accepted taxpayer money under the Troubled Assets Relief Program (TARP) in 2008. It was legal for TARP recipient firms to pay bonuses—indeed, some lawyers argued that failing to pay promised bonuses would violate contract law—but many taxpayers believed it was unethical.

Some cultures have systems of respect and honor that require tribute and compensation for service, while others may view payment as a form of bribe. It may be legal in one country to make a donation or support a public official in order to gain influence over a decision, but it may be unethical. In some countries, it may be both illegal and unethical. Given the complexity of human values and their expression across behaviors, it is wise to research the legal and ethical norms of the place or community where you want to do business.

Global Village

International trade has advantages and disadvantages, again based on your viewpoint and cultural reference. If you come from a traditional culture, with strong gender norms and codes of conduct, you may not appreciate the importation of some Western television programs that promote what you consider to be content that contradicts your cultural values. You may also take the viewpoint from a basic perspective and assert that basic goods and services that can only be obtained through trade pose a security risk. If you cannot obtain the product or service, it may put you, your business, or your community at risk.

Furthermore, “just in time” delivery methods may produce shortages when the systems break down due to weather, transportation delays, or conflict. People come to know each other through interactions (and transactions are fundamental to global trade), but cultural viewpoints may come into conflict. Some cultures may want a traditional framework to continue and will promote their traditional cultural values and norms at the expense of innovation and trade. Other cultures may come to embrace diverse cultures and trade, only to find that they have welcomed some who wish to do harm. In a modern world, transactions have a cultural dynamic that cannot be ignored.

Intercultural communication and business have been related since the first exchange of value. People, even from the same community, had to arrive at a common understanding of value. Symbols, gestures, and even language reflect these values. Attention to this central concept will enable the skilled business communicator to look beyond his or her own viewpoint.

It was once the privilege of the wealthy to travel, and the merchant or explorer knew firsthand what many could only read about. Now we can take virtual tours of locations we may never travel to, and as the cost of travel decreases, we can increasingly see the world for ourselves. As global trade has developed, and time to market has decreased, the world has effectively grown smaller. While the size has not changed, our ability to navigate has been dramatically decreased. Time and distance are no longer the obstacles they once were. The Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan, a pioneer in the field of communication, predicted what we now know as the “global village.” The global village is characterized by information and transportation technologies that reduce the time and space required to interact (McLuhan, M., 1964).

Key Takeaway

People create political, legal, economic, and ethical systems to guide them in transacting business domestically and internationally.

LICENSE