Introduction to Chinese Religions

Religious practices in ancient China go back over 7,000 years. Long before the philosophical and spiritual teachings of Confucius and Lao-Tzu developed or before the teachings of the Buddha came to China, the people worshipped personifications of nature and then of concepts like “wealth” or “fortune” which developed into a religion. These beliefs still influence religious practices today. For example, the Tao te Ching of Taoism maintains that there is a universal force known as the Tao which flows through all things and binds all things but makes no mention of specific gods to be worshipped; still, modern Taoists in China (and elsewhere) worship many gods at private altars and in public ceremonies which originated in the country’s ancient past. (24)

An Overview of Chinese Religious History

Chinese Prehistoric Religious Practice

In China, religious beliefs are evident in the Yangshao Culture of the Yellow River Valley, which prospered between 5000-3000 BCE. At the Neolithic site of Banpo Village in modern Shaanxi Province (dated to between c. 4500–3750 BCE) 250 tombs were found containing grave goods, which point to a belief in life after death. There is also a ritualistic pattern to how the dead were buried with tombs oriented west to east to symbolize death and rebirth. Grave goods provide evidence of specific people in the village who acted as priests and presided over some kind of divination and religious observance.

The Yangshao Culture was matrilineal, meaning women were dominant, so this religious figure would have been a woman based on the grave goods found. There is no evidence of any high-ranking males in the burials, but a significant number of females. Scholars believe that the early religious practices were also matrilineal and most likely animistic, where people worship personifications of nature, and usually feminine deities were benevolent and male deities malevolent, or at least more to be feared.

These practices continued with the Qijia Culture (c. 2200–1600 BCE) who inhabited the Upper Yellow River Valley but whose culture could have been patriarchal. Examinations of the Bronze Age site of Lajia Village in modern-day Qinghai Province (and elsewhere) have uncovered evidence of religious practices. Lajia Village is often referred to as the “Chinese Pompeii” because it was destroyed by an earthquake, which caused a flood and the resulting mudslides buried the village intact. Among the artifacts uncovered was a bowl of noodles which scientists have examined and believe to be the oldest noodles in the world and precursors to China’s staple dish “Long-Life Noodles.” Even though not all scholars or archaeologists agree on China as the creator of the noodle, the finds at Lajia support the claim of religious practices there as early as c. 2200 BCE. There is evidence that the people worshipped a supreme god who was king of many other lesser deities. (24)

Religious Practice During the Shang Dynasty

By the time of the Shang Dynasty (1600–1046 BCE) these religious beliefs had developed so that now there was a definite “k ing of the gods ” named Shangti and many lesser gods of other names. Shangti presided over all the important matters of state and was a very busy god. He was rarely sacrificed to because people were encouraged not to bother him with their problems. Ancestor worship may have begun at this time but more likely, started much earlier.

Evidence of a strong belief in ghosts , in the form of amulets and charms , goes back to at least the Shang Dynasty and ghost stories are among the earliest form of Chinese literature. Ghosts (known as guei or kuei) were the spirits of deceased persons who had not been buried correctly with due honors or were still attached to the earth for other reasons. They were called by a number of names but in one form, jiangshi (“stiff body”), they appear as zombies . Ghosts played a very important role in Chinese religion and culture and still do. The ritual still practiced in China today known as Tomb Sweeping Day (usually around 4 April) is observed to honor the dead and make sure they are happy in the afterlife. If they are not, they are thought to return to haunt the living. The Chinese visit the graves of their ancestors on Tomb Sweeping Day during the Festival of Qingming, even if they never do at any other time of the year, to tend the graves and pay their respects.

When someone died naturally or was buried with the proper honors, there was no fear of them returning as a ghost. The Chinese believed that, if the person had lived a good life, they went to live with the gods after death. These spirits of one’s ancestors were prayed to so they could approach Shangti with the problems and praise of those on earth. Tanner (2010) writes:

Ancestors were represented by a physical symbol such as a spirit tablet engraved or painted with the ancestor’s honorific name. Rituals were held to honor these ancestors, and sacrifices of millet ale, cattle, dogs, sheep, and humans were offered. The scale of the sacrifices varied, but at important rituals, hundreds of animals and/or human sacrifices would be slaughtered. Believing that the spirits of the dead continued to exist and to take an interest in the world of the living, the Shang elite buried their dead in elaborate and well-furnished tombs.

The spirits of these ancestors could help a person in life by revealing the future to them. Divination became a significant part of Chinese religious beliefs and was performed by people with mystical powers (what one would call a “psychic” in the modern day) one would pay to tell one’s future through oracle bones. It is through these oracle bones that writing developed in China. The mystic would write the question on the shoulder bone of an ox or turtle shell and apply heat until it cracked; whichever way the crack went would determine the answer. It was not the mystic or the bone that gave the answer but one’s ancestors who the mystic communed with. These ancestors were in touch with eternal spirits, the gods, who controlled and maintained the universe. (24)

Religious Practice During the Zhou Dynasty

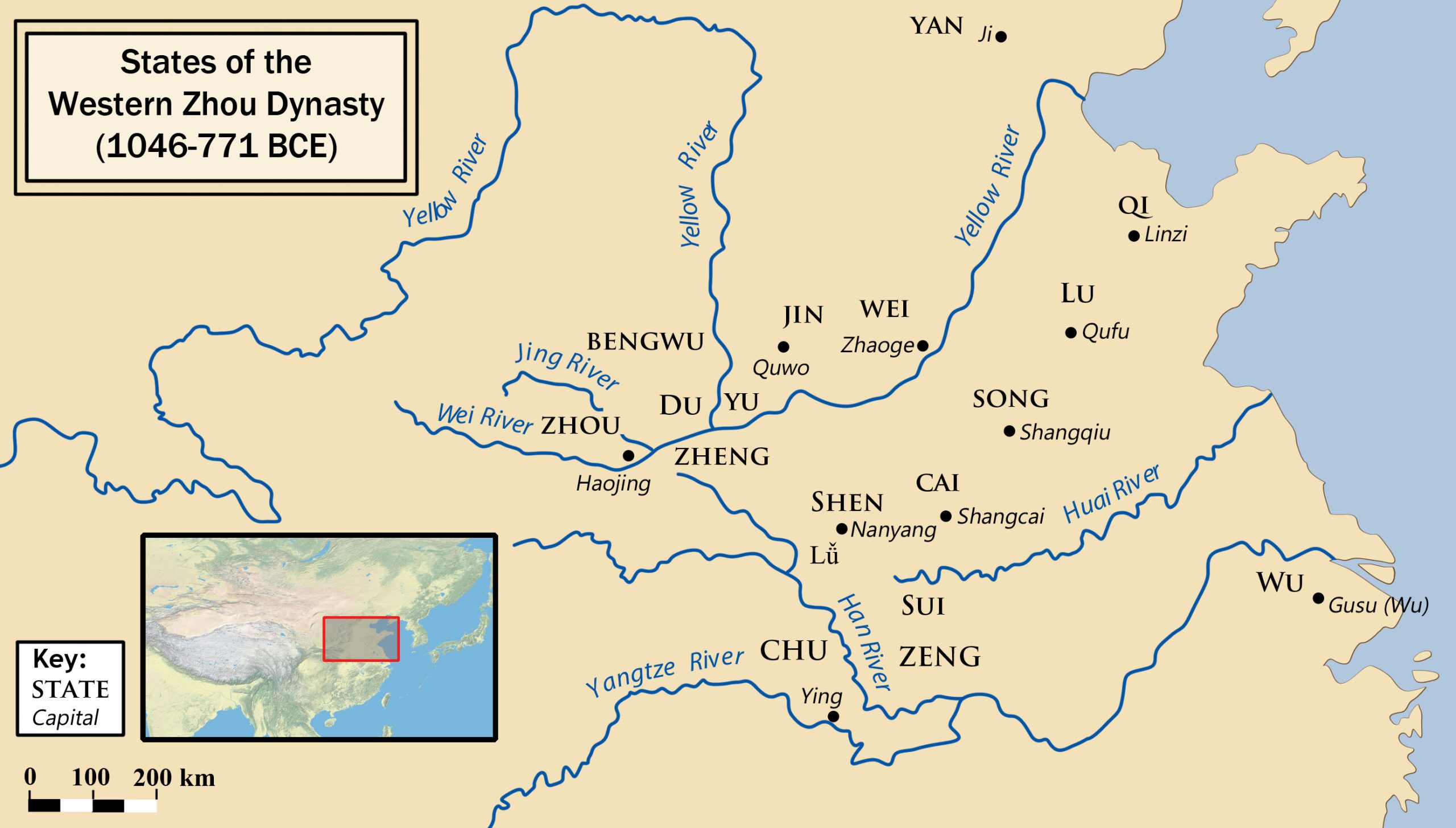

In the Zhou Dynasty (c. 1046–226 BCE) the concept of the Mandate of Heaven was developed. The Mandate of Heaven was the belief that Shangti ordained a certain emperor or dynasty to rule and allowed them to rule as long as they pleased him. When the rulers were no longer taking care of the people responsibly, they were said to have lost the Mandate of Heaven and were replaced by another. Modern scholars have seen this simply as a justification for changing a regime, but the people at the time believed in the concept. The gods were thought to watch over the people and would pay special attention to the emperor. People continued a practice, which began toward the end of the Shang Dynasty, of wearing charms and amulets of their god of choice or their ancestors for protection or in the hope of blessings, and the emperor did this as well. Religious practices changed during the latter part of the Zhou Dynasty owing to its decline and eventual fall, but the practice of wearing religious jewelry continued.

The Zhou Dynasty is divided into two periods: Western Zhou (1046–771 BCE) and Eastern Zhou (771–226 BCE). Chinese culture and religious practices flourished during the Western Zhou period but began to break apart during the Eastern Zhou. Religious practices of divination, ancestor worship, and veneration for the gods continued, but during the Spring and Autumn Period (772–476 BCE) philosophical ideas began to challenge the ancient beliefs.

Confucius (c. 551–479 BCE) encouraged ancestor worship as a way of remembering and honoring one’s past but emphasized people’s individual responsibility in making choices and criticized an over-reliance on supernatural powers. Mencius (c. 372–289 BCE) developed the ideas of Confucius, and his work resulted in a more rational and restrained view of the world.

The work of Lao-Tzu (c. 500 BCE) and the development of Taoism might be seen as a reaction to Confucian principles if not for the fact that Taoism developed many centuries before the traditional date assigned to Lao-Tzu.

It is much more probable that Taoism developed from the original nature/folk religion of the people of China than that it was created by a 6th-century BCE philosopher. Therefore, it is more accurate to say that the rationalism of Confucianism probably developed as a reaction to the emotionalism and spiritualism of those earlier beliefs. (24)

Warring States Period

Religious beliefs developed further during the next period in China’s history, The Warring States Period (476–221 BCE), which was very chaotic. The seven states of China were all independent now that the Zhou had lost the Mandate of Heaven, and each one fought the others for control of the country. Confucianism was the most popular belief during this time, but there was another, which was growing stronger.

A statesman named Shang Yang (died 338 BCE) from the region of Qin developed a philosophy called Legalism , which maintained that people were only motivated by self-interest, were inherently evil, and had to be controlled by law. Shang Yang’s philosophy helped the State of Qin overpower the six other states and from that the Qin Dynasty was founded by the first emperor, Shi Huangti, in 221 BCE. (24)

Daoism: An Overview

Taoism (also known as Daoism ) is a Chinese philosophy attributed to Lao Tzu (c. 500 BCE), which contributed to the folk religion of the people primarily in the rural areas of China and became the official religion of the country under the Tang Dynasty. Taoism is therefore both a philosophy and a religion. It emphasizes doing what is natural and ” going with the flow ” in accordance with the Tao (or Dao), a cosmic force which flows through all things and binds and releases them. The notion that humans should reconnect with their natural selves by “going with the flow” is called wu wei .

The philosophy grew from an observance of the natural world, and the religion developed out of a belief in cosmic balance maintained and regulated by the Tao. The original belief may or may not have included practices, such as ancestor and spirit worship, but both of these principles are observed by many Taoists today and have been for centuries.

Taoism exerted a great influence during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE) and the emperor Xuanzong (reigned 712–756 CE) decreed it a state religion, mandating that people keep Taoist writings in their home. It fell out of favor as the Tang Dynasty declined and was replaced by Confucianism and Buddhism but the religion is still practiced throughout China and other countries today. (25)

Origins of Daoism

The historian Sima Qian (145–86 BCE) tells the story of Lao-Tzu , a curator at the Royal Library in the state of Chu, who was a natural philosopher. Lao-Tzu believed in the harmony of all things and that people could live easily together if they only considered each other’s feelings once in a while and recognized that their self-interest was not always in the interest of others. Lao-Tzu grew impatient with people and with the corruption he saw in government, which caused the people so much pain and misery. He was so frustrated by his inability to change people’s behavior that he decided to go into exile.

As he was leaving China through the western pass, the gatekeeper Yin Hsi stopped him because he recognized him as a philosopher. Yin Hsi asked Lao-Tzu to write a book for him before he left civilization forever and Lao-Tzu agreed. He sat down on a rock beside the gatekeeper and wrote the Tao-Te-Ching (The Book of the Way) . He stopped writing when he felt he was finished, handed the book to Yin Hsi, and walked through the western pass to vanish into the mist beyond. Sima Qian does not continue the story after this, but presumably (if the story is true) Yin Hsi would have then had the Tao-Te-Ching copied and distributed.

The Tao Te Ching

The Tao-Te-Ching is not a ‘scripture’ in any way. It is a book of poetry presenting the simple way of following the Tao and living life at peace with one’s self, others, and the world of changes.

A typical verse advises, ” Yield and overcome /Empty and become full/ Bend and become straight ” to direct a reader to a simpler way of living.

Instead of fighting against life and others, one can yield to circumstances and let the things, which are not really important go. Instead of insisting one is right all the time, one can empty one’s self of that kind of pride and be open to learning from other people. Instead of clinging to old belief patterns and hanging onto the past, one can bend to new ideas and new ways of living.

The Tao-Te-Ching was most likely not written by Lao-Tzu at the western pass and may not have been written by him at all. Lao-Tzu probably did not exist and the Tao-Te-Ching is a compilation of sayings set down by an unknown scribe. Whether the origin of the book and the belief system originated with a man named Lao-Tzu or when it was written or how, is immaterial (the book itself would agree); all that matters is what the work says and what it has come to mean to readers.

The Tao-Te-Ching is an attempt to remind people that they are connected to others and to the earth and that everyone could live together peacefully if people would only be mindful of how their thoughts and actions affect themselves, others, and the earth.

Yin-Yang Thought

A good reason to believe that Lao-Tzu was not the author of the Tao-Te-Ching is that the core philosophy of Taoism grew up from the peasant class during the Shang Dynasty long before the accepted dates for Lao-Tzu. During the Shang era, the practice of divination became more popular through the reading of oracle bones, which would tell one’s future. Reading oracle bones led to a written text called the I-Ching (c. 1250–1150 BCE), the Book of Changes , which is a book still available today providing a reader with interpretations for certain hexagrams, which supposedly tell the future.

A person would ask a question and then throw a handful of yarrow sticks onto a flat surface (such as a table) and the I-Ching would be consulted for an answer to the person’s question. These hexagrams consist of six unbroken lines (calledYang ) and six broken lines (called Yin ). When a person looked at the pattern the yarrow sticks made when they were thrown, and then consulted the hexagrams in the book, they would have their answer. The broken and the unbroken lines, the yin and yang , were both necessary for that answer because the principles of yin and yang were necessary for life.

“Yin-yang thought began as an attempt to answer the question of the origin of the universe. According to yin-yang thought, the universe came to be as a result of the interactions between the two primordial opposing forces of yin and yang. Because things are experienced as changing, as processes coming into being and passing out of being, they must have both yang , or ” being ,” and yin , or ” lack of being .” The world of changing things that constitutes nature can exist only when there are both yang and yin. Without yang nothing can come into existence. Without yin nothing can pass out of existence.”

Although Taoism and the Tao-Te-Ching were not originally associated with the symbol known as the yin-yang, they have both come to be because the philosophy of Taoism embodies the yin-yang principle and yin-yang thought . Life is supposed to be lived in balance, as the symbol of the yin and the yang expresses. The yin-yang is a symbol of opposites in balance – dark/light, passive/aggressive, female/male – everything except good and evil, life and death, because nature does not recognize anything as good or evil and nature does not recognize a difference between life and non-life. All is in harmony in nature, and Taoism tries to encourage people to accept and live that kind of harmony as well. (25)

Taoist Beliefs

Other Chinese texts relating to Taoism are the Chaung-Tzu (also known as the Zhuangzi, written by Zhuang Zhou, c. 369–286 BCE) and the Daozang from the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE) and Song Dynasty (960–1234 CE), which was compiled in the later Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 CE). All of these texts are based on the same kinds of observation of the natural world and the belief that human beings are innately good and only needed a reminder of their inner nature to pursue virtue over vice. There are no “bad people” according to Taoist principles, only people who behave badly. Given the proper education and guidance toward understanding how the universe works, anyone could be a “good person” living in harmony with the earth and with others.

According to this belief, the way of the Tao is in accordance with nature while resistance to the Tao is unnatural and causes friction. The best way for a person to live, according to Taoism, is to submit to whatever life brings and be flexible. If a person adapts to the changes in life easily, that person will be happy; if a person resists the changes in life, that person will be unhappy. One’s ultimate goal is to live at peace with the way of the Tao and recognize that everything that happens in life should be accepted as part of the eternal force, which binds and moves through all things.

Unlike Buddhism (which came from India but became very popular in China), Taoism arose from the observations and beliefs of the Chinese people. The principles of Taoism impacted Chinese culture greatly because it came from the people themselves and was a natural expression of the way the Chinese understood the universe. The concept of the importance of a harmonious existence of balance fit well with the equally popular philosophy of Confucianism (also native to China). Taoism and Confucianism were aligned in their view of the innate goodness of human beings, but differed in how to bring that goodness to the surface and lead people to act in better, unselfish, ways.

Taoist Rituals

This belief in allowing life to unfold in accordance with the Tao does not extend to Taoist rituals, however. The rituals of Taoist practice are absolutely in accordance with the Taoist understanding, but have been influenced by Buddhist and Confucian practices so that, in the present day, they are sometimes quite elaborate. Every prayer and spell which makes up a Taoist ritual or festival must be spoken precisely and every step of the ritual observed perfectly.

Taoist religious festivals are presided over by a Grand Master (a kind of High Priest ) who officiates, and these celebrations can last anywhere from a few days to over a week. During the ritual, the Grand Master and his assistants must perform every action and recitation in accordance with tradition or else their efforts are wasted. This is an interesting departure from the usual Taoist understanding of ” going with the flow ” and not worrying about external rules or elaborate religious practices.

Taoist rituals are concerned with honoring the ancestors of a village, community, or city, and the Grand Master will invoke the spirits of these ancestors while incense burns to purify the area. Purification is a very important element throughout the ritual. The common space of everyday life must be transformed into sacred space to invite communion with the spirits and the gods. There are usually four assistants who attend the Grand Master in different capacities, either as musicians, sacred dancers, or readers. The Grand Master will act out the text as read by one of his assistants, and this text has to do with the ascent of the soul to join with the gods and one’s ancestors. In ancient times, the ritual was performed on a staircase leading to an altar to symbolize ascent from one’s common surroundings to the higher elevation of the gods. In the present day, the ritual may be performed on a stage or the ground, and it is understood from the text and the actions of the Grand Master that he is ascending.

The altar still plays an important part in the ritual as it is seen as the place where the earthly realm meets with the divine. Taoist households have their own private altars where people will pray and honor their ancestors, household spirits, and the spirits of their village. Taoism encourages individual worship in the home, and the rituals and festivals are community events which bring people together, but they should not be equated with worship practices of other religions such as attending church or temple. A Taoist can worship at home without ever attending a festival, and throughout its history most people have. Festivals are very expensive to stage and are usually funded by members of the town, village, or city. They are usually seen as celebrations of community, though are sometimes performed in times of need such as an epidemic or financial struggle. The spirits and the gods are invoked during these times to drive away the dark spirits causing the problems.

Legacy

Taoism significantly influenced Chinese culture from the Shang Dynasty forward. The recognition that all things and all people are connected is expressed in the development of the arts, which reflect the people’s understanding of their place in the universe and their obligation to each other. During the Tang Dynasty, Taoism became the state religion under the reign of the emperor Xuanzong because he believed it would create harmonious balance in his subjects and, for a while, he was correct. Xuanzong’s rule is still considered one of the most prosperous and stable in the history of China and the high point of the Tang Dynasty.

Taoism has been nominated as a state religion a number of times throughout China’s history but the majority preferred the teachings of Confucius (or, at times, Buddhism), most likely because of the rituals of these beliefs, which provide a structure Taoism lacks. Today, Taoism is recognized as one of the great world religions and continues to be practiced by people in China and throughout the world. (25)

Religious Practice During the Qin and Han Empires

Qin Dynasty

During the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE), Shi Huangti banned religion and burned philosophical and religious works. Legalism became the official philosophy of the Qin government and the people were subject to harsh penalties for breaking even minor laws. Shi Huangti outlawed any books, which did not deal with his family line, his dynasty, or Legalism, even though he was personally obsessed with immortality and the afterlife, and his private library was full of books on these subjects. Confucian scholars hid books as best as they could and people would worship their gods in secret but were no longer allowed to carry amulets or wear religious charms.

Han Dynasty

Shi Huangti died in 210 BCE while searching for immortality on a tour through his kingdom. The Qin Dynasty fell soon after, in 206 BCE, and the Han Dynasty took its place. The Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE) at first continued the policy of Legalism but abandoned it under Emperor Wu (141–87 BCE). Confucianism became the state religion and grew more and more popular even though other religions, like Taoism, were also practiced.

During the Han Dynasty, the emperor became distinctly identified as the mediator between the gods and the people. The position of the emperor had been seen as linked to the gods through the Mandate of Heaven from the early Zhou Dynasty, but now it was his express responsibility to behave so that heaven would bless the people.

Arrival of Buddhism

In the 1st century CE, Buddhism arrived in China via trade through the Silk Road. According to the legend, the Han emperor Ming (28–75 CE) had a vision of a golden god flying through the air and asked his secretary who that could be. The assistant told him he had heard of a god in India who shone like the sun and flew in the air, and so Ming sent emissaries to bring Buddhist teachings to China. Buddhism quickly combined with the earlier folk religion and incorporated ancestor worship and veneration of Buddha as a god.

Buddhism was welcomed in China and took its place alongside Confucianism, Taoism, and the blended folk religion as a major influence on the spiritual lives of the people. When the Han Dynasty fell, China entered a period known as The Three Kingdoms (220–263 CE), which was similar to the Warring States Period in bloodshed, violence, and disorder. The brutality and uncertainty of the period influenced Buddhism in China which struggled to meet the spiritual needs of the people at the time by developing rituals and practices of transcendence. The Buddhist schools of Ch’an (better known asZen ), Pure Land, and others took on form at this time. (24)

Religious Practice During the Empire and Beyond

The major religious influences on Chinese culture were in place by the time of the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE) but there were more to come. The second emperor, Taizong (626–649 CE), was a Buddhist who believed in toleration of other faiths and allowed Manichaeism, Christianity, and others to set up communities of faith in China. His successor, Wu Zeitian (690–704 CE), elevated Buddhism and presented herself as a Maitreya (a future Buddha) while her successor, Xuanzong (712–756 CE), rejected Buddhism as divisive and made Taoism the state religion.

Although Xuanzong allowed and encouraged all faiths to practice in the country, by 817 CE Buddhism was condemned as a dividing force, which undermined traditional values. Between 842–845 CE Buddhist nuns and priests were persecuted and murdered and temples were closed. Any religion other than Taoism was prohibited, and persecutions affected communities of Jews, Christians, and any other faith. The emperor Xuanzong II (846–859 CE) ended these persecutions and restored religious tolerance. The dynasties, which followed the Tang up to the present day all had their own experiences with the development of religion and the benefits and drawbacks which come with it, but the basic form of what they dealt with was in place by the end of the Tang Dynasty. (24)

Rise of the Song Dynasty

The chaos and political void caused by the collapse of the Tang Dynasty led to the break-up of China into five dynasties and ten kingdoms, but one warlord would, as had happened so often before, rise to the challenge and collect at least some of the various states back into a resemblance of a unified China.

The Song Dynasty was, thus, founded. Although the Song Dynasty were able to govern over a united China after a significant period of division, their reign was beset by the problems of a new political and intellectual climate which questioned imperial authority and sought to explain where it had gone wrong in the final years of the Tang dynasty. A symptom of this new thinking was the revival of the ideals of Confucianism, Neo-Confucianism as it came to be called, which emphasized the improvement of the self within a more rational metaphysical framework. This new approach to Confucianism, with its metaphysical add-on, now allowed for a reversal of the prominence the Tang had given to Buddhism, seen by many intellectuals as a non-Chinese religion. (55)

Foundation of Chinese Culture

Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism, and the early folk religion combined to form the basis of Chinese culture. Other religions have added their own influences but these four belief structures had the most impact on the country and the culture. Religious beliefs have always been very important to the Chinese people even though the People’s Republic of China originally outlawed religion when it took power in 1949 CE. The People’s Republic saw religion as unnecessary and divisive, and during the Cultural Revolution temples were destroyed, churches burned, or converted to secular uses. In the 1970’s CE the People’s Republic relaxed its stand on religion and since then has worked to encourage organized religion as “psychologically hygienic” and a stabilizing influence in the lives of its citizens. (24)

Confucianism: An Overview

Confucius (or Kongzi) was a Chinese philosopher who lived in the 6th century BCE and whose thoughts, expressed in the philosophy of Confucianism , have influenced Chinese culture right up to the present day. Confucius has become a larger than life figure and it is difficult to separate the reality from the myth. He is considered the first teacher and his teachings are usually expressed in short phrases, which are open to various interpretations. Chief among his philosophical ideas is the importance of a virtuous life, filial piety and ancestor worship. Also emphasized is the necessity for benevolent and frugal rulers, the importance of inner moral harmony and its direct connection with harmony in the physical world and that rulers and teachers are important role models for wider society.

Life of Confucius

Confucius is believed to have lived from c. 551 to c. 479 BCE in the state of Lu (now Shandong or Shantung). However, the earliest written record of him dates from some four hundred years after his death in the Historical Records of Sima Qian (or Si-ma Ts‘ien). Raised in the city of Qufu (or K‘u-fou), Confucius worked for the Prince of Lu in various capacities, notably as the Director of Public Works in 503 BCE and then the Director of the Justice Department in 501 BCE. Later, he travelled widely in China and met with several minor adventures, including imprisonment for five days due to a case of mistaken identity. Confucius met the incident with typical restraint and was said to have calmly played his lute until the error was discovered. Eventually, Confucius returned to his hometown where he established his own school in order to provide students with the teachings of the ancients. Confucius did not consider himself a ‘creator’ but rather a ‘transmitter’ of these ancient moral traditions. Confucius’ school was also open to all classes, rich and poor.

It was whilst he was teaching in his school that Confucius started to write. Two collections of poetry were the Book of Odes (Shijing or Shi king) and the Book of Documents (Shujing or Shu king). The Spring and Autumn Annals (Lin Jing or Lin King), which told the history of Lu, and the Book of Changes (Yi Jing or Yi king) was a collection of treatises on divination.

Unfortunately for posterity, none of these works outlined Confucius’ philosophy. Confucianism, therefore, had to be created from second-hand accounts and the most reliable documentation of the ideas of Confucius is considered to be theAnalects , although even here there is no absolute evidence that the sayings and short stories were actually said by him and often the lack of context and clarity leave many of his teachings open to individual interpretation.

The other three major sources of Confucian thought are Mencius , Great Learning , and Mean . With Analects , these works constitute the Four Books of Confucianism , otherwise referred to as, the Confucian Classics . Through these texts, Confucianism became the official state religion of China from the second century BCE. (26)

Confucian Philosophy

The Confucian system looks less like a religion than a philosophy or way of life. This may be because it focuses on earthly relationships and duty and not on deities or the divine. Confucianism teaches that the gentleman-scholar is the highest calling. Confucius believed that the gentleman, or junzi , is a role model and the highest calling for a person. The gentleman holds fast to high principles regardless of life’s hardships. The gentleman does not remove himself from the world but fulfills his capacity for goodness. He does so by a commitment to virtue developed through moral formation.

Though ritual is quite important, there is not much concern with an afterlife or eschatology. Whereas a religion like Hinduism devotes much of its doctrine to accomplishing spiritual fulfillment, Confucianism is concerned with social fulfillment. Unlike Buddhism, there are no monks. There are no priests or religious leaders. It does not have many of the conventions of a religion.

Confucius did not give his followers a god or gods to be worshipped. Confucianism is not against worship, but teaches that social duties are more important. The focus is on ethical behavior and good government and social responsibility. (26)

Relationships

Relationships are important in Confucianism. Order begins with the family. Children are to respect their parents. A son ought to study his father’s wishes as long as the father lives; and after the father is dead, he should study his life, and respect his memory (Confucius 102).

A person needs to respect the position that s/he has in all relationships. Due honor must be given to those people above and below oneself. This makes for good social order. The respect is typified through the idea of Li . Li is the term used to describe Chinese proprietary rites and good manners. These include ritual, etiquette, and other facets that support good social order. The belief is that when Li is observed, everything runs smoothly and is in its right place.

Relationships are important for a healthy social order and harmony. The relationships in Li are

- Father over son

- Older brother over younger

- Husband over wife

- Ruler over subject

- Friend is equal to Friend

Each of these relationships is important for balance in a person’s life. There are five main relationship principles : hsiao ,chung , yi , xin , and jen .

- Hsiao is love within the family. Examples include love of parents for their children and of children for their parents. Respect in the family is demonstrated through Li and Hsiao.

- Chung is loyalty to the state. This element is closely tied to the five relationships of Li. Chung is also basic to the Confucian political philosophy. An important note is that Confucius thought that the political institutions of his day were broken. He attributed this to unworthy people being in positions of power. He believed rulers were expected to learn self-discipline and lead through example.

- Yi is righteousness or duty in an ordered society. It is an element of social relationships in Confucianism. Yi can be thought of as internalized Li.

- Xin is honesty and trustworthiness. It is part of the Confucian social philosophy. Confucius believed that people were responsible for their actions and treatment of other people. Jen and Xin are closely connected.

- Jen is benevolence and humaneness towards others. It is the highest Confucian virtue and can also be translated as love. This is the goal for which individuals should strive.

Together, these principles balance people and society. A balanced, harmonious life requires attention to one’s social position.

For Confucius, correct relationships establish a well-ordered hierarchy in which each individual fulfills her/his duty. (1)

Confucian Rituals

Birth rituals center on T’ai-shen or the spirit of the fetus. These rituals are designed to protect an expectant mother. A special procedure is prescribed for disposal of placenta. The mother is given a special diet and is allowed rest for a month after delivery. The mother’s family supplies all the items required by the baby on the first, fourth and twelfth monthly anniversaries of the birth. Maturity is no longer being celebrated, except in traditional families. A ceremony in which a group meal is served celebrates a young adult who is coming of age; s/he is served chicken.

Marriage rituals are very important. They are conducted in six stages. At the proposal stage, the couple exchanges eight Chinese characters. These characters are the year, month, day, and hour of each of their births. If anything unfavorable happens within the bride-to-be’s family during the next three days, the proposal is considered to have been rejected. The engagement stage occurs after the wedding day is selected. The bride may announce the wedding with invitations and a gift of cookies made in the shape of the moon. This is the formal announcement. The dowry is the third stage. The bride’s family carries it to the groom’s home in a procession. The bride-price is then sent to the bride by the groom’s parents. Gifts by the groom to the bride, equal in value to the dowry, are sent to her. Procession is the fourth stage. It is brief but important. The groom visits the bride’s home and brings her back to his house. The procession is accompanied by a great deal of singing and drum beating. The marriage ceremony and reception is the stage in which the couple recite their vows, toast each other with wine, and then take center stage at a banquet. The morning after the ceremony is the final stage. The bride serves breakfast to the groom’s parents, who then reciprocate. This completes the marriage.

Death rituals seem elaborate to many Westerners. At the time of death, the relatives cry loudly. This is a way of informing the neighbors. The family begins mourning. They dress in clothes made of rough material. The corpse is washed and placed in a coffin. Mourners bring incense and money to offset the cost of the funeral. Food and significant objects of the deceased are placed in the coffin. A Buddhist, Christian, or Taoist priest performs the burial ceremony. Liturgies are performed on the seventh, ninth, and forty-ninth days after the burial. On the first and third anniversaries of the death, friends, and family follow the coffin to the cemetery. They carry a willow branch which symbolizes the soul of the person who has died. The branch is carried back to the family altar where it is used to “install” the spirit of the deceased.

Legacy

Following his death in 479 BCE, Confucius was buried in his family’s tomb in Qufu (in Shandong) and, over the following centuries, his stature grew so that he became the subject of worship in schools during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) and temples were established in his name at all administrative capitals during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE). Throughout the imperial period an extensive knowledge of the fundamental texts of Confucianism was a necessity in order to pass the civil service selection examinations. Educated people often had a tablet of Confucius’ writings prominently displayed in their houses and sometimes also statues, most often seated and dressed in imperial costume to symbolize his status as ‘the king without a throne’. Portrait prints were also popular, especially those taken from the lost original attributed to Wu Daozi (or Wu Taoutsi) and made in the 8th century CE. Unfortunately, no contemporary portrait of Confucius survives but he is most often portrayed as a wise old man with long grey hair and moustaches, sometimes carrying scrolls.

The teachings of Confucius and his followers have, then, been an integral part of Chinese education for centuries and the influence of Confucianism is still visible today in contemporary Chinese culture with its continued emphasis on family relationships and respect, the importance of rituals, the value given to restraint and ceremonies, and the strong belief in the power and benefits of education. (26)

“Confucianism and Daoism” by Dr. Kathryn Weinland is adapted from “Confucianism and Daoism” in World Religions by Lumen Learning as published by Florida State College at Jacksonville, licensed CC BY except where otherwise noted.

Licensing and attribution information updated by Kathy Essmiller, 3.16.23. Please contact kathy.essmiller@okstate.edu with corrections or suggestions.

(24) — Religion in Ancient China by Emily Mark published in Ancient History Encyclopedia is licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0 .

(25) — Taoism by Emily Mark published in Ancient History Encyclopedia is licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0 .

(26) — Confucius by Mark Cartwright published in Ancient History Encyclopedia is licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0 .