Islam: A Brief Introduction

Islam is a monotheistic and Abrahamic religion articulated by the Qur’an, a book considered by its adherents to be the verbatim word of God (Allāh) and by the teachings and normative example (called the Sunnah and composed of Hadith) of Muhammad, considered by them to be the last prophet of God. An adherent of Islam is called a Muslim.

Muslims believe that God is one and incomparable and the purpose of existence is to love and serve God. Muslims also believe that Islam is the complete and universal version of a primordial faith that was revealed at many times and places before, including through Abraham, Moses, and Jesus, whom they consider prophets. Muslims maintain that the previous messages and revelations have been partially misinterpreted or altered over time, but consider the Arabic Qur’an to be both the unaltered and the final revelation of God. Religious concepts and practices include the five pillars of Islam, which are basic concepts and obligatory acts of worship, and following Islamic law, which touches on virtually every aspect of life and society, providing guidance on multifarious topics from banking and welfare, to warfare and the environment.

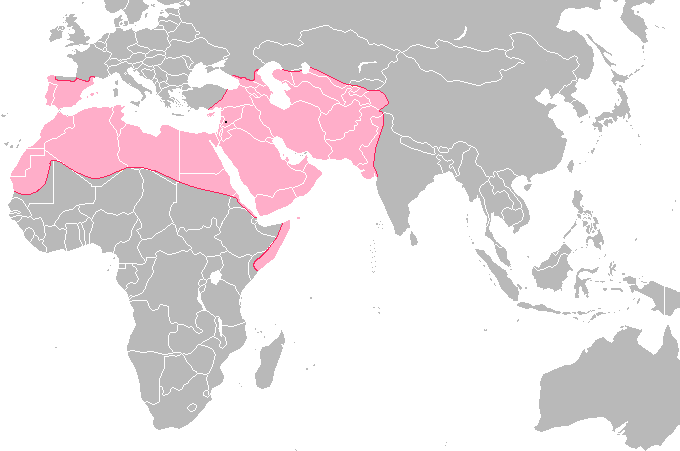

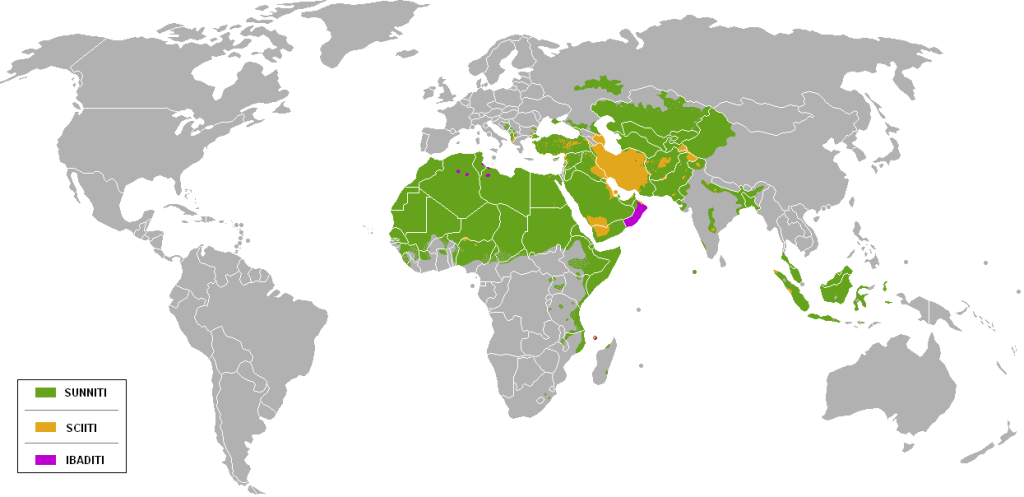

Most Muslims are of two denominations, Sunni (75–90%), or Shia (10–20%). About 13% of Muslims live in Indonesia, the largest Muslim-majority country, 25% in South Asia, 20% in the Middle East, and 15% in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sizable minorities are also found in China, Russia, and the Americas. Converts and immigrant communities are found in almost every part of the world (see Islam by country). With about 1.57 billion followers or 23% of earth’s population, Islam is the second-largest religion and one of the fastest-growing religions in the world. (45)

A Brief History of Muhammad

In Muslim tradition, Muhammad (c. 570 – June 8, 632) is viewed as the last in a series of prophets. During the last 22 years of his life, beginning at age 40 in 610 CE, according to the earliest surviving biographies, Muhammad reported revelations that he believed to be from God conveyed to him through the archangel Gabriel (Jibril). The content of these revelations, known as the Qur’an, was memorized and recorded by his companions. During this time, Muhammad preached to the people in Mecca, imploring them to abandon polytheism and to worship one God. Although some converted to Islam, Muhammad and his followers were persecuted by the leading Meccan authorities.

After 12 years of the persecution of Muslims by the Meccans and the Meccan boycott of Muhammad’s relatives, Muhammad and the Muslims performed the Hijra (“emigration”) to the city of Medina (formerly known as Yathrib) in 622 CE. There, with the Medinan converts and the Meccan migrants, Muhammad in Medina established his political and religious authority. A state was established in accordance with Islamic economic jurisprudence.

Within a few years, two battles were fought against the Meccan forces:

- First, the Battle of Badr in 624 CE, which was a Muslim victory.

- Then a year later, when the Meccans returned to Medina, the Battle of Uhud, which ended inconclusively.

The Arab tribes in the rest of Arabia then formed a confederation and during the Battle of the Trench besieged Medina with the intent of finishing off Islam. In 628 CE, a treaty was signed between Mecca and the Muslims and was broken by Mecca two years later. After the signing of the treaty many more people converted to Islam. At the same time, Meccan trade routes were cut off as Muhammad brought surrounding desert tribes under his control. By 629 CE Muhammad was victorious in the nearly bloodless Conquest of Mecca, and by the time of his death in 632 CE (at the age of 62) he united the tribes of Arabia into a single religious polity. (45)

The Early Caliphates

With Muhammad’s death in 632 CE, disagreement broke out over who would succeed him as leader of the Muslim community. Abu Bakr, a companion and close friend of Muhammad, was made the first caliph. The Quran was compiled into one book during this time.

Abu Bakr’s death in 634 CE resulted in the succession of Umar ibn al-Khattab as the caliph, followed by Uthman ibn al-Affan, Ali ibn Abi Talib, and Hasan ibn Ali. The first caliphs are known as the “Rightly Guided Caliphs.” Under them, the territory under Muslim rule expanded deeply into the Persian and Byzantine territories. When Umar was assassinated in 644 CE, the election of Uthman as successor was met with increasing opposition. The Quran was standardized during this time. In 656 CE, Uthman was also killed, and Ali assumed the position of caliph. After the first civil war (the “First Fitna”), Ali was assassinated by the Kharijites in 661 CE. Following this, Mu’awiyah seized power and began the Umayyad Dynasty. (45)

After being united under the aegis of Islam, the Arabs—known as the Umayyads—began military campaigns outside of their realm. In the mid-seventh century, Muslim armies began invading parts of the increasingly vulnerable Sassanid and Byzantine empires, claiming land in what are now Egypt, Syria, and Palestine. In fact, so powerful were the Islamic army and navy that Byzantium was permanently crippled by the invasions.

The Umayyads went on to conquer northern Africa and invade India, building a kingdom that exceeded the size of the Roman Empire. But despite their success abroad, the Umayyads suffered a period of discord at home: a succession dispute resulted in a division of Muslims into Sunni and Shi’a factions. While the Sunnis retained temporary control of the caliphate, a Shi’ite uprising in 750 CE toppled the Umayyads and established Abbasid rule. Under the Abbasids, mass conversion to Islam was encouraged, as was a dynamic Afro-Eurasian trade network. The Abbasids also established Persian as the official language, and encouraged the flowering of Islamic culture. (46)

When a Shi’a leader—Abu al-Abbas—usurped power from the reigning Sunni caliph in 750 CE, the Umayyad era officially came to a close. While al-Abbas tried to execute all members of the Sunni Umayyads, one leader escaped to the Iberian Peninsula, where he established a new Umayyad kingdom. However, Abd ar-Rahman I was not the first Muslim to invade Spain; Muslim Berbers had overthrown the Visigoths and established the kingdom of Al-Andalus in the early eighth century. Still, the Umayyads in Spain—known as the Caliphate of Cordoba—retained power until the 1000s. With the decline of the Caliphate, several smaller kingdoms, called “taifas,” claimed control over southern Spain. It was not until 1492, when the Christian monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella declared a holy war against the Spanish Muslims did Muslim control of the regions come to an end. (47)

Islam in Late Middle Ages

The Mongols —nomads of central Eurasia—dominated world history during the thirteenth century. The Mongols invaded many postclassical empires and built an extensive cultural and commercial network. Led by Chinggis Khan and his successors, the Mongols brought China, Persia, Tibet, Eurasia Minor, and southern Russia under their control. The Mongol Empire also opened trade routes—primarily along the Silk Road —as well as lines of communication between Asia and the Middle East. Under Hulegu Khan, the Mongols sacked the Abbasid capital at Baghdad and decimated much of the Islamic civilization. They killed the last Abbasid caliphate and established the Ilkhanate, which ruled Persia until the fourteenth century. The Ilkhans embraced many religions, particularly Christianity, in their quest to create an alliance with Europe. However, beginning in 1295, the Ilkhans converted to Islam. (48)

The Crusades—a series of religious wars launched to restore Christian control of the Holy Land—began in 1096 and were the most conspicuous sign of the rise and expansion of Christian Europe. The first crusade resulted in the division of Syria and Palestine into smaller Christian kingdoms, although subsequent crusades had less successful outcomes. Under the Muslim ruler Saladin, most of the Holy Land was reclaimed for Islam by the late 1100s; by 1251, Muslim armies had expelled all Christian kingdoms. The impact of the Crusades was twofold: first, they established a precedent for the rift between Western Christendom and the Middle Eastern Muslim world and second, they intensified commercial contact between the two regions. While Europeans were interested in obtaining textiles, scientific knowledge, and medicine from the Muslim world, Muslims had little interest in European goods or culture. (49)

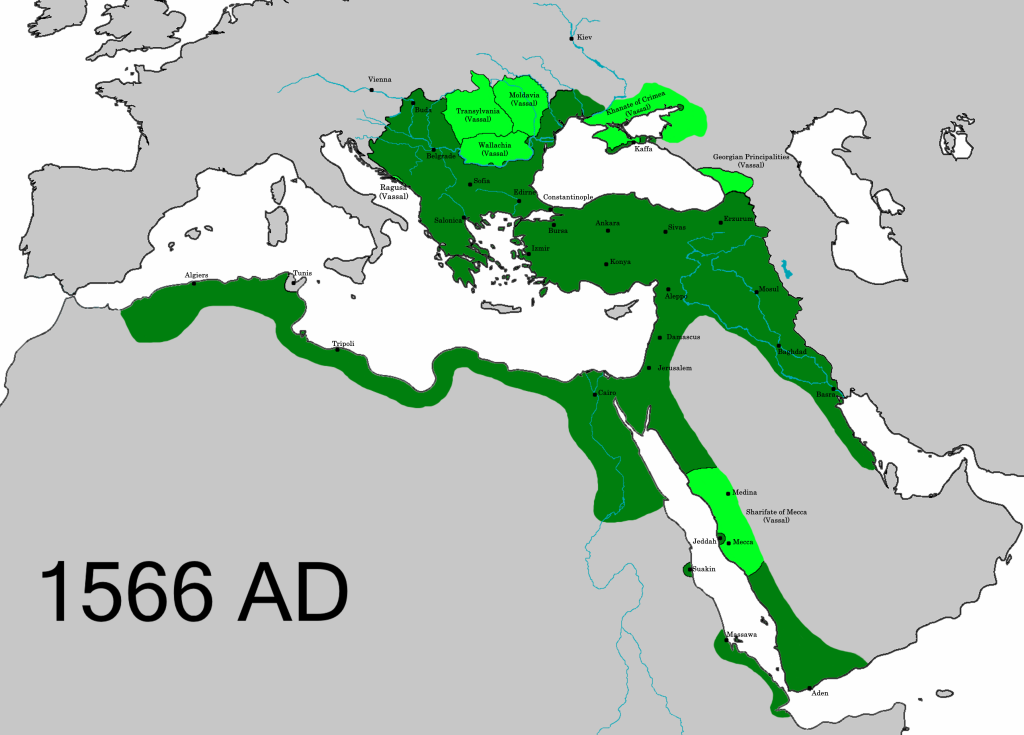

Two powerful Muslim empires emerged in the Middle East in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. The Ottomans ruled Asia Minor, eastern Europe, northern Africa, and parts of the Middle East, while the Safavids built an empire that included present-day Afghanistan and Iran. Both, however, possessed a religious zeal for the expansion of Islam. The Ottomans emerged in the wake of Mongol defeat: they invaded the Balkans, captured Constantinople, and toppled Byzantium, forging a military state ruled by a sultanate and dominated by a warrior aristocracy. The Safavids also rose to power in the wake of the Mongol invasions. The Safavids were Shi’a Muslims who claimed leadership and established rule by a shah and his court. Both the Ottomans and the Safavids encouraged Islamic learning and cultural advancement while also bolstering trade. (50)

Islam in the Modern Era (1924–present)

By the nineteenth century, the Ottoman Empire was in decline. The Ottomans, their imperial holdings much reduced since their heyday in the sixteenth century, became increasingly dependent on European resources to buoy their empire. Beginning in the late 1800s, Ottoman leaders embarked upon a policy of reform that they believed would modernize their state by implementing constitutional government, educational systems, new technology, and new industry with European monies. As a result of this financial dependence, many European powers began to dominate or annex Ottoman holdings in the Middle East in the 1800s. With the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the Ottomans allied themselves with the Central Powers—Austria-Hungary and Germany—but were defeated by the Allied forces in 1918. (51)

The collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the end of World War I, and the discovery of oil allowed European powers to gain new influence in the Middle East. Near the end of World War I, Britain and France negotiated for the partition of the Middle East between them, proclaiming territorial “mandates.” In addition, Britain promised European Zionists a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Not only were Britain and France interested in expanding their influence in the Middle East, but they were keen on exploiting the Middle East’s primary resource: oil. Oil fueled the development of industrial Europe, and by mandating control over Middle Eastern countries; Britain and France were guaranteed access to sought-after petroleum products.

Beginning in 1940s, Britain and France abandoned their protectorates and ended their mandates in the Middle East, largely due to conflicts that erupted between local governments and their foreign occupiers. Between 1941 and 1947, Iran, Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Iraq, and Egypt (with the exception of the British-dominated Suez Canal) became independent of European rule. And in 1948, Zionists established the state of Israel, a declaration that precipitated the 1948 Arab-Israeli war and decades of subsequent conflict. However, while many Middle Eastern nations became independent of British and French rule in the 1940s, the onset of the Cold War attracted new foreign interest in the region. As a result, the United States and the Soviet Union vied for control of the Middle East throughout much of the twentieth century. (52)

The Islamic Revolution of 1979 (also known as the Iranian Revolution) overthrew the reigning shah (king) and established a theocratic state. The leader of the revolt, a Shi’ite Muslim cleric, proclaimed himself Ayatollah—or “supreme leader”—of Iran.

The Ayatollah asserted the importance of the Islamic faith and decried Western influence and policy. The revolution established an important precedent in the Middle East by encouraging the proliferation of an Islamic ideology throughout the region. As a result, in the 1980s and 1990s, many fundamentalist Muslim groups emerged, including Al Qaeda and the Taliban. Many of these groups embraced an extreme strain of Islam as well as violent anti-Western sentiment. Islamic fundamentalists were responsible for numerous terrorist attacks against Western powers, including the 1998 embassy bombings in Africa and the September 11, 2001 attacks in New York City. (53)

At the same time, new Muslim intellectuals are beginning to arise, and are increasingly separating perennial Islamic beliefs from archaic cultural traditions. Liberal Islam is a movement that attempts to reconcile religious tradition with modern norms of secular governance and human rights. Its supporters say that there are multiple ways to read Islam’s sacred texts, and stress the need to leave room for “independent thought on religious matters.” Women’s issues receive a significant weight in the modern discourse on Islam. (45)

Articles of Faith

God

Islam’s most fundamental concept is a rigorous monotheism. Allāh is the term that Muslims use to refer to God. In Islam, God is beyond all comprehension and Muslims are not expected to visualize God. God is described and referred to by certain names or attributes, the most common being Al-Rahmān, meaning “The Compassionate” and Al-Rahī m, meaning “The Merciful” (See Names of God in Islam). Muslims believe that the creation of everything in the universe was brought into being by God’s sheer command, ” ‘Be’ and so it is, ” and that the purpose of existence is to worship God.

Angels

Belief in angels is fundamental to the faith of Islam. The Arabic word for angel (malak) means, “messenger.” According to the Qur’an, angels do not possess free will; they worship and obey God in total obedience. Angels’ duties include:

- Communicating revelations from God

- Glorifying God

- Recording every person’s actions

- Taking a person’s soul at the time of death

Muslims believe that angels are made of light.

Revelations

Muslims believe that the verses of the Qur’an were revealed to Muhammad by God through the Archangel Gabriel (Jibrīl) on many occasions between 610 CE until his death on June 8, 632 CE. While Muhammad was alive, all of these revelations were written down by his companions (sahabah), although the prime method of transmission was orally through memorization.

The Qur’an is divided into 114 suras, or chapters, which combined, contain 6,236 āyāt, or verses. The chronologically earlier suras, revealed at Mecca, are primarily concerned with ethical and spiritual topics. The later Medinan suras mostly discuss social and moral issues relevant to the Muslim community. The Qur’an is more concerned with moral guidance than legal instruction, and is considered the “sourcebook of Islamic principles and values.” Muslim jurists consult the hadith, or the written record of Prophet Muhammad’s life, to both supplement the Qur’an and assist with its interpretation. The science of Qur’anic commentary and exegesis is known as tafsir. Rules governing proper pronunciation are called tajwid.

Muslims usually view “the Qur’an” as the original scripture as revealed in Arabic and that any translations are necessarily deficient, which are regarded only as commentaries on the Qur’an.

Prophets

Muslims identify the prophets of Islam as those humans chosen by God to be his messengers. According to the Qur’an, the descendants of Abraham were chosen by God to bring the “Will of God” to the peoples of the nations. Muslims believe that prophets are human and not divine, though some are able to perform miracles to prove their claim. Islamic theology says that all of God’s messengers preached the message of Islam—submission to the will of God. The Qur’an mentions the names of numerous figures considered prophets in Islam, including Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses and Jesus, among others.

In Islam, the “normative” example of Muhammad’s life is called the Sunnah (literally “trodden path”). This example is preserved in traditions known as hadith (“reports”), which recount his words, his actions, and his personal characteristics.

Resurrection and Judgment

Belief in the “Day of Resurrection,” Yawm al-Qiyāmah is also crucial for Muslims. They believe the time of Qiyāmah is preordained by God but unknown to man. The trials and tribulations preceding and during the Qiyāmah are described in the Qur’an and the hadith, and also in the commentaries of scholars. The Qur’an emphasizes bodily resurrection, a break from the pre-Islamic Arabian understanding of death.

On the Day of Resurrection, Muslims believe all mankind will be judged on their good and bad deeds. The Qur’an lists several sins that can condemn a person to hell, such as disbelief in God, and dishonesty; however, the Qur’an makes it clear God will forgive the sins of those who repent if he so wills. Good deeds, such as charity, prayer and compassion towards animals, will be rewarded with entry to heaven. Muslims view heaven as a place of joy and bliss, with Qur’anic references describing its features and the physical pleasures to come. Mystical traditions in Islam place these heavenly delights in the context of an ecstatic awareness of God.

Art

Making images of human beings and animals is frowned on in many Islamic cultures with image-makers receiving punishment in the Day of Resurrection. However this rule has been interpreted in different ways by different scholars and in different historical periods, and there are examples of paintings of both animals and humans in Mughal, Persian, and Turkish art. The existence of this aversion to creating images of animate beings has been used to explain the prevalence of calligraphy, tessellation, and pattern as key aspects of Islamic artistic culture. (45)

Five Pillars of Islam

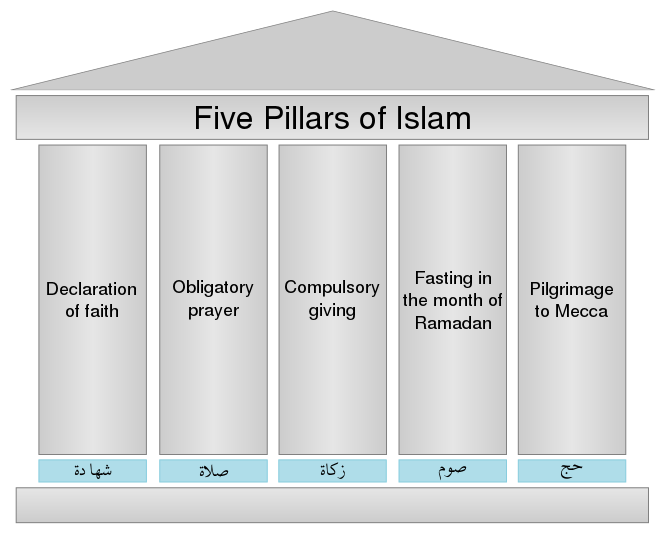

The Pillars of Islam are five basic acts in Islam, considered obligatory for all believers. The Quran presents them as a framework for worship and a sign of commitment to the faith. They are:

- Shahadah (creed)

- Daily prayers (salat)

- Almsgiving (zakah)

- Fasting during Ramadan

- Pilgrimage to Mecca (hajj) at least once in a lifetime

The Shia and Sunni sects both agree on the essential details for the performance of these acts.

Prayer

Ritual prayers, called Ṣalāh or Ṣalāt, must be performed five times a day. Salah is intended to focus the mind on God, and is seen as a personal communication with him that expresses gratitude and worship. Salah is compulsory but flexibility in the specifics is allowed depending on circumstances. The prayers are recited in the Arabic language, and consist of verses from the Qur’an.

A mosque is a place of worship for Muslims, who often refer to it by its Arabic name, masjid. The word mosque in English refers to all types of buildings dedicated to Islamic worship, although there is a distinction in Arabic between the smaller, privately owned mosque and the larger, “collective” mosque. Although the primary purpose of the mosque is to serve as a place of prayer, it is also important to the Muslim community as a place to meet and study. Modern mosques have evolved greatly from the early designs of the 7th century, and contain a variety of architectural elements such as minarets.

Alms-giving

“Zakāt” (“alms”) is giving a fixed portion of accumulated wealth by those who can afford it to help the poor or needy and for those employed to collect Zakat; also, for bringing hearts together, freeing captives, for those in debt (or bonded labour) and for the (stranded) traveller. It is considered a religious obligation (as opposed to voluntary charity) that the well-off owe to the needy because their wealth is seen as a “trust from God’s bounty.” Conservative estimates of annual Zakat are estimated to be 15 times global humanitarian aid contributions. The amount of zakat to be paid on capital assets (e.g. money) is 2.5% (1/40), for people who are not poor. The Qur’an and the hadith also urge a Muslim to give even more as an act of voluntary alms-giving called ṣadaqah.

Fasting

Fasting (ṣawm) from food and drink (among other things) must be performed from dawn to dusk during the month of Ramadhan. The fast is to encourage a feeling of nearness to God, and during it, Muslims should express their gratitude for and dependence on him, atone for their past sins, and think of the needy. Sawm is not obligatory for several groups for whom it would constitute an undue burden. For others, flexibility is allowed depending on circumstances, but missed fasts usually must be made up quickly.

Pilgrimage

The pilgrimage, called the ḥajj, has to be done during the Islamic month of Dhu al-Hijjah in the city of Mecca. Every able-bodied Muslim who can afford it must make the pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in his or her lifetime. Rituals of the Hajj include:

- Walking seven times around the Kaaba

- Walking seven times between Mount Safa and Mount Marwah recounting the steps of Abraham’s wife, while she was looking for water in the desert before Mecca developed into a settlement

- Spending a day in the desert at Mina and then a day in the desert in Arafat praying and worshiping God and following the foot steps of Abraham

- Symbolically stoning the Devil in Mina recounting Abraham’s actions (45)

Schools of Islam

Sunni

The largest denomination in Islam is Sunni Islam, which makes up 75%–90% of all Muslims. Sunni Muslims also go by the name Ahl as-Sunnah, which means “people of the tradition [of Muhammad].” These hadiths (“reports”), recounting Muhammad’s words, actions, and personal characteristics, are preserved in traditions known as Al-Kutub Al-Sittah (six major books). Sunnis believe that the first four caliphs were the rightful successors to Muhammad; since God did not specify any particular leaders to succeed him and those leaders were elected.

Shia

The Shi’a constitute 10–20% of Islam and are its second-largest branch.

Shia Islam has several branches, the largest of which is the Twelvers, followed by Zaidis and Ismailis. After the death of Imam Jafar al-Sadiq (the great grand son of Abu Bakr and Ali ibn Abi Talib) considered the sixth Imam by the Shia’s, the Ismailis started to follow his son Isma’il ibn Jafar and the Twelver Shia’s (Ithna Asheri) started to follow his other son Musa al-Kazim as their seventh Imam. The Zaydis follow Zayd ibn Ali, the uncle of Imam Jafar al-Sadiq, as their fifth Imam.

While Sunnis believe that Muhammad did not appoint a successor and a caliph should be chosen by the whole community, the Twelver Shias and the Ismaili Shias believe that during Muhammad’s final pilgrimage to Mecca, he appointed his son-in-law, Ali ibn Abi Talib, as his successor in the Hadith of the pond of Khumm. As a result, they believe that Ali ibn Abi Talib was the first Imam (leader), rejecting the legitimacy of the previous Muslim caliphs Abu Bakr, Uthman ibn al-Affan and Umar ibn al-Khattab.

Sufism

Sufism is a mystical-ascetic approach to Islam that seeks to find divine love and knowledge through direct personal experience of God. By focusing on the more spiritual aspects of religion, Sufis strive to obtain direct experience of God by making use of “intuitive and emotional faculties” that one must be trained to use. However, Sufism has been criticized by the Salafi sect for what they see as an unjustified religious innovation. Many Sufi orders, or tariqas, can be classified as either Sunni or Shi’a, but others classify themselves simply as “Sufi.” (45)

Women in Islam

Women play a vital role in the story of Muhammad. Muhammad’s loss of his own mother at an early age provides some context for his sensitivity to the cause of women throughout his life. When Muhammad began spending many hours alone in prayer, for instance, one of his concerns was the widespread discrimination he witnessed against women. Later in life, Muhammad will take on wives deemed poor and outcast by society as an act of kindness. In terms of his own story, Muhammad’s first wife, Khadijah — a woman fifteen years his elder — will give the future prophet his first job as a caravan driven. Later, after Muhammad’s first encounter with Gabriel left him frightened, Khadijah is also the one who consoles the future prophet, even encouraging him to return to the cave of his encounter. Khadijah is also among the first to convert to the new religion as well.

Muhammad’s second wife, Aisha, will serve as an important figure for verifying Muhammad’s piousness. She reports, for instance, “I saw the Prophet being inspired Divinely on a very cold day and noticed the sweat dropping from his forehead (as the Inspiration was over).” Aisha also proves pivotal in that her father, Abu Bakr, becomes the first recognized caliph following Muhammad’s passing. Muhammad’s daughter, Fatima, will prove an important figure as well, her husband Ali becoming the fourth caliphs and the rightful successor of Muhammad within the Shiite Islamic tradition. (1)

After the rise of Islam, the Quran (the word of God) and the Hadith (the traditions of the prophet Muhammad) developed into Sharia, or Islamic religious law. Sharia dictates that women should cover themselves with a veil. Women who follow these traditions feel in wearing the hijab is their claim to respectability and piety. One of the relevant passages from the Quran translates as:

“O Prophet! Tell thy wives and daughters, and the believing women, that they should cast their outer garments over their persons, that are most convenient, that they should be known and not molested. And Allah is Oft-Forgiving, Most Merciful” (Quran Surat Al-Ahzab 33:59).

These areas of the body are known as “awrah” (parts of the body that should be covered) and are referred to in both the Quran and the Hadith. “Hijab” can also be used to refer to the seclusion of women from men in the public sphere.

In pre-Islamic Arabian culture, women had little control over their marriages and were rarely allowed to divorce their husbands. Marriages usually consisted of an agreement between a man and his future wife’s family, and occurred either within the tribe or between two families of different tribes. As part of the agreement, the man’s family might offer property, such as camels or horses in exchange for the woman. Upon marriage, the woman would leave her family and reside permanently in the tribe of her husband. Marriage by capture, or “Ba’al,” was also a common pre-Islamic practice.

Under Islam, polygyny (the marriage of multiple women to one man) is allowed, but not widespread. In some Islamic countries, such as Iran, a woman’s husband may enter into temporary marriages in addition to permanent marriage. Islam forbids Muslim women from marrying non-Muslims. (56)

“Islam” by Dr. Kathryn Weinland is adapted from “Islam” in World Religions by Lumen Learning as published by Florida State College at Jacksonville, licensed CC BY except where otherwise noted.

Licensing and attribution information updated by Kathy Essmiller, 3.16.23. Please contact kathy.essmiller@okstate.edu with corrections or suggestions.

(1) — Content by Florida State College at Jacksonville is licensed under CC-BY 4.0 .

(45) — Islam by Wikipedia for Schools is licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0 .

(46) — Islam, The Middle East, and the West (Unit 3: Arab Conquests and the Rise of the Caliphate) by Saylor Academy is licensed under CC-BY 3.0 .

(47) — Islam, The Middle East, and the West (Unit 4: The Expansion of Islam into Europe ) by Saylor

(48) — Islam, The Middle East, and the West (Unit 6: The Mongol Invasions) by Saylor Academy is licensed under CC-BY 3.0 .

(49) — Islam, The Middle East, and the West (Unit 5: The Crusades) by Saylor Academy is licensed under CC-BY 3.0 .

(50) — Islam, The Middle East, and the West (Unit 7: The Ottomans and the Safavids) by Saylor Academy is licensed under CC-BY 3.0.

(51) — Islam, The Middle East, and the West (Unit 8: European Challenges and the Ottoman Empire) by Saylor Academy is licensed under CC-BY 3.0 .

(52) — Islam, The Middle East, and the West (Unit 9: The Islamic World in an Age of European Domination) by Saylor Academy is licensed under CC-BY 3.0 .

(53) — Islam, The Middle East, and the West (Unit 11: The Islamic Revolution, Terrorism, and the West) by Saylor Academy is licensed under CC-BY 3.0 .

(54) — Constantine I by Donald L. Wasson published in Ancient History Encyclopedia is licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0 .

(55) — Song Dynasty by Mark Cartwright published in Ancient History Encyclopedia is licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0 .

(56) — Women in Pre-Islamic Arabia by Lumen from Boundless World History is licensed under CC-BY-SA 4.0 .