A Toolkit for Statewide Mixed-Methods Research on OER Adoption: A Case Study from Washington’s Community and Technical Colleges

Boyoung Chae

This chapter presents a methodological case study from Washington’s Community and Technical College system, where a two-phase, mixed-methods project was designed to explore faculty engagement with open educational resources. Instead of emphasizing research results, the chapter details how the study was developed and carried out, highlighting practical decisions made at each stage, from stakeholder collaboration and instrument design to recruitment, data collection, and analysis. Drawing on lessons learned, it offers a replicable toolkit for others conducting OER research across multi-campus systems. The chapter is intended to support researchers and institutions aiming to produce rigorous, context-aware, and policy-relevant evidence around OER use.

Introduction

As Open Educational Resources (OER) continue to gain momentum in higher education, researchers, policymakers, and institutional leaders are increasingly seeking robust, scalable data to inform decisions about their adoption, implementation, and overall effectiveness. Meeting this demand requires research approaches capable of addressing both the breadth of system-wide trends and the depth of localized, context-specific faculty experiences. However, designing large-scale studies that achieve this balance remains a methodological challenge, particularly within multi-institution systems.

To address this gap, this chapter presents a methodological case study of a statewide mixed-methods research conducted in Washington’s Community and Technical College (WA CTC) system. Rather than focusing on the study’s findings, the chapter offers a detailed account of the research design and implementation process. Central to this account is a practical, replicable toolkit outlining strategies used across each phase of the project, from stakeholder engagement and instrument design to data collection, analysis, and dissemination.

By foregrounding the research process itself, and offering this toolkit, this chapter aims to support other researchers, institutions, and policymakers seeking to conduct rigorous and actionable OER studies at scale.

A Practical Toolkit for Replicable OER Research

This toolkit (Table 1) is not a theoretical model, but a set of tested strategies developed through real-world application in a complex, multi-campus system. It offers actionable guidance for each stage of the research process, planning, recruitment, data collection, analysis, and dissemination, with examples rooted in the Washington case.

Table 1

A Toolkit for Replicable OER Research

| Stage | Strategies |

|---|---|

| Planning and Preparation | Leverage Existing Governance Structures: Engage established governance bodies—such as statewide faculty councils, instructional leadership groups, or OER working groups—to share updates about your research and gather early feedback. These forums can increase cross-institutional awareness and offer a non-coercive space for input on timing, relevance, and communication channels.

For institutions or systems that lack centralized OER governance, consider forming temporary advisory groups or informal faculty working circles that serve a similar coordination function. Even a small, representative group of engaged faculty or instructional designers can provide meaningful feedback and support dissemination by sharing recruitment materials through their local networks. Conduct a Pre-Study Environmental Scan: Informally conduct a preliminary environmental scan to identify system-level trends, needs, or tensions. This may involve small-scale exploratory methods such as brief focus group interviews, mini surveys, or informal stakeholder consultations. These early insights can inform the development of research instruments and guide sampling strategies. Align Timing with Academic Calendars: Schedule data collection during periods when faculty are most likely to be available. Coordinate early with institutions to gain access to relevant mailing lists or communication channels. Center Faculty Expertise in Recruitment Materials: Frame participation as an opportunity to influence OER policy and practice. Emphasize respect for faculty perspectives and recognize the value of their time and expertise. Ensure Representation Across Roles and Institutions: Use purposive sampling to ensure participants reflect the full diversity of the system, including variations in institutional type, faculty role, and discipline. Pay particular attention to groups often underrepresented in OER research, such as part-time instructors, faculty in professional technical programs, and those at smaller or rural campuses. Importantly, include faculty who are not currently using OER or who express skepticism about its value. Understanding the concerns, constraints, or misconceptions of non-adopters is critical for designing policies and supports that foster broader adoption across varied contexts. |

| Research Design and Instrument Design | Sequence Methods to Capture Breadth and Depth: Employ a layered research design that begins with a quantitative survey to identify broad patterns, followed by qualitative interviews to explore faculty’s day-to-day experiences with OER in greater depth.

Design for Depth, Not Just Brevity: While short surveys are often favored due to time constraints, overly brief instruments risk generating shallow data. In OER research, this can obscure the complexity of adoption decisions, pedagogical practices, or institutional barriers. Instead of limiting length, focus on a clear, intuitive structure with purposeful, well-sequenced questions. When designed effectively, even longer surveys can achieve high engagement (see this example of a comprehensive OER faculty survey) Design Instruments Iteratively Across Phases: In multi-phase studies, develop initial instruments (e.g., surveys) informed by prior OER research, then revise or expand subsequent instruments (e.g., interview protocols) based on findings from earlier phases. This iterative approach ensures coherence across phases and facilitates deeper exploration of emerging themes. Design a Semi-Structured Interview Protocol: Create an interview protocol that includes consistent core questions to enable comparison across participants, while allowing flexibility to follow up on context-specific issues. In OER research, this approach supports the identification of both shared patterns and institution-specific insights. Use Open-Ended Questions in Interviews: Incorporate open-ended prompts that invite participants to reflect on their individual experiences with OER adoption and implementation (see Table 2 for sample open-ended questions used to explore faculty perspectives with OER). |

| Data Collection | Structure Qualitative Data Collection Around Faculty Narratives: Center qualitative data collection on faculty narratives that trace their full engagement with OER—from initial exposure to current practices. Encourage participants to reflect on pedagogical shifts, institutional supports, and perceived impacts on students. This storytelling approach can reveal both challenges and transformative moments.

Capture Institutional Contexts Concurrently: Alongside faculty interviews, collect institutional artifacts (e.g., OER policies, communications, or course materials) or conduct brief interviews with administrators. These additional sources help triangulate how OER is framed at the institutional level versus how it is experienced by individual faculty. Offer Flexible Participation Options: Provide multiple modes of participation (e.g., Zoom, phone, in-person) to accommodate varied faculty preferences and schedules, reducing participation barriers. |

| Data Analysis | Analyze Qualitative Data Using Structured, Context-Aware Approaches: Apply thematic or domain analysis to identify patterns in how faculty adopt, adapt, and perceive OER. Attend to differences across institutional roles, disciplines, and teaching contexts. Track not only what faculty say, but how they frame their experiences—paying attention to tensions, motivations, and perceived trade-offs related to cost, pedagogy, or institutional support.

Establish methodological rigor: Ensure the credibility and trustworthiness of the research through established strategies such as triangulation (e.g., comparing survey and interview data), thick description (rich contextualization of findings), and member checking (sharing interpretations with participants for validation). Include Faculty Anecdotes Alongside Each Key Finding: Use brief quotes to illustrate faculty's lived experience with OER. These anecdotes not only validate the interpretations but also make the findings more compelling. |

| Dissemination | Translate Findings into Actionable Recommendations: Provide policy recommendations when findings reveal structural or systemic factors affecting OER adoption. Offer administrative recommendations when findings highlight faculty needs related to institutional support for OER use.

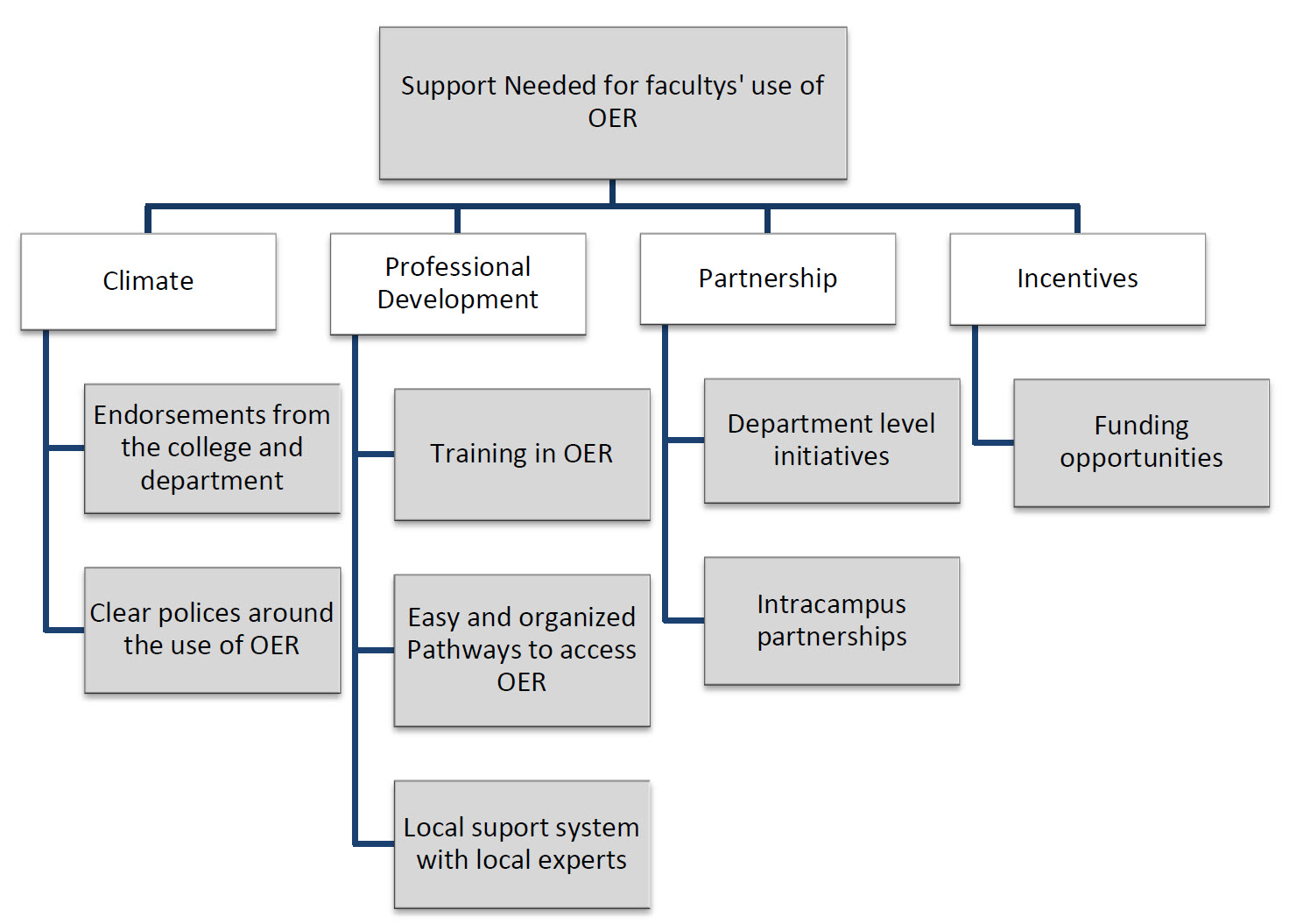

Incorporate Visual Representations: Use diagrams, flowcharts, or tables to visually synthesize key findings. These visuals help bridge narrative depth with analytical structure and offer immediately applicable models for institutional use (see Figure 1 for an example). Engage Multiple Audiences with Targeted Communication: Disseminate findings to researchers, policymakers, and practitioners using tailored formats that reflect the needs and expectations of each audience. |

To operationalize several of the strategies described above, particularly those related to qualitative data collection, faculty narratives, and institutional context, researchers may benefit from a set of thoughtfully designed interview prompts. The open-ended questions in Table 2 were developed to elicit rich, practice-based insights from faculty engaged in various stages of OER adoption. They are intended to support semi-structured interviews that explore both systemic factors and individual experiences.

Table 2

| Question | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Can you walk me through the first time you decided to adopt OER? | Elicit a narrative about the initial motivations and contextual factors that led to OER adoption. |

| Imagine you were leading open education efforts across our college system, with unlimited funding at your disposal. What kinds of supports would you design to help faculty adopt, use, and grow their engagement with OER? | Encourage visionary thinking about structural change and faculty-centered support strategies. |

| How has adopting OER influenced the way you design or teach your courses? | Explore how OER adoption shapes teaching practices and course design. |

| Have you noticed any changes in student success—such as engagement, course completion, or retention—since adopting OER? If so, how do you interpret those changes? | Examine how OER adoption relates to student success outcomes. |

| Have you ever chosen not to use OER in a course? What influenced that decision? | Surface contextual barriers or strategic decisions that limited adoption. |

| What kinds of institutional support have helped—or hindered—your OER work? | Identify systemic enablers or pain points. |

| How do your colleagues or department perceive OER? Has that shifted over time? | Examine departmental culture, peer influence, and diffusion of innovation. |

| Describe a moment when OER changed the way you approached your course—positively or negatively. | Prompt reflection on emotionally significant experiences. |

| If you had the power to redesign your institution’s OER support system, what would it look like? | Invite imaginative, policy-relevant insights tied to faculty needs. |

| Do you see OER as aligned with your values or teaching philosophy? Why or why not? | Reveal underlying professional identity and philosophical alignment |

Figure 1

Applying the Toolkit in Practice

This section illustrates how the toolkit was grounded in the Washington Community and Technical College (WA CTC) system study. Developed inductively, the toolkit emerged through the design, implementation, and reflection on a large-scale, mixed-methods investigation into faculty engagement with OER. Each component of the toolkit represents a strategy that proved effective, necessary, or insightful during the study. Together, they offer a replicable and evidence-based framework for conducting statewide or multi-institutional OER research.

The study was conducted in two phases: (1) a quantitative survey distributed to faculty across all 34 WA CTC institutions and (2) qualitative interviews with a diverse sample of instructors drawn from the survey pool. The following sections describe how the toolkit’s core strategies emerged from the practical realities of this process.

Planning and Institutional Coordination

The decision to structure the research as a multi-phase, mixed-methods project was intentional. At the outset, the researchers recognized that while interest in OER was growing, both nationally and within Washington State, the available data lacked the depth needed to inform meaningful policy and support mechanisms at the college or system level. To meet this need, the study began with a broad survey to establish statewide patterns, followed by in-depth qualitative interviews that explored faculty perspectives more deeply. This layered approach aligned with the toolkit’s emphasis on balancing breadth with depth, and allowed researchers to draw connections between institutional trends and individual experiences.

Initial planning focused on laying the groundwork for system-wide participation. The research team presented the project across various state-level councils to raise awareness, build partnerships, and gather logistical support. While no formal advisory group was established, early collaboration with campus OER leads, librarians, and instructional designers proved instrumental in refining the research design and preparing for broad outreach. These early efforts also helped identify appropriate communication channels and secure permissions where needed—both of which were essential for effective survey distribution and faculty recruitment. This proactive coordination enhanced institutional trust and laid the foundation for strong response rates.

Data Collection: Survey

The first phase of data collection involved a statewide survey distributed through official communication channels of the State Board for Community and Technical Colleges (SBCTC) and through campus-wide emails. Faculty were encouraged to participate by emphasizing the value of their input in shaping statewide OER strategies. A total of 718 faculty members completed the survey, representing a wide range of academic disciplines, institution types, and instructional roles, including a significant number of adjunct instructors.

The survey captured faculty awareness and usage of OER, their perceptions of its benefits and barriers, and their interest in future support. While the results provided useful patterns and broad insights, they also revealed important limitations. The survey alone could not explain the diversity of implementation practices, the underlying pedagogical motivations, or the contextual challenges unique to different institutions. These gaps helped shape the design of the second phase.

Data Collection: Interview

To build on the survey findings, the second phase employed qualitative interviews. Faculty who indicated interest in a follow-up were considered, and a group of 60 participants was selected using criterion sampling. The selection aimed to reflect a diverse cross-section of disciplines, institution sizes and types, geographic locations, and instructional modalities. Particular attention was given to including adjunct faculty, whose perspectives are often underrepresented, and to ensuring regional and institutional diversity. OER advocates, including librarians, instructional designers, and eLearning coordinators, also played a role in identifying and encouraging potential participants.

The interview protocol was semi-structured and designed to invite open, reflective conversations. Faculty were asked to describe their personal journeys with OER, including their motivations for adopting it, the support they received, the challenges they encountered, and the perceived impact on their teaching and students. Interviews were conducted by phone and typically lasted between 40 and 60 minutes. All interviews were recorded with participants’ consent, transcribed, and supported by researcher field notes. The research team followed standard ethical procedures, including informed consent and confidentiality protections.

Framing the interviews as opportunities to contribute to statewide policy development and institutional improvement encouraged honest and thoughtful responses. Many participants expressed appreciation for the chance to reflect on their work, suggesting that the interview process itself served as a meaningful form of professional reflection.

Data Analysis

Interview transcripts were analyzed using Spradley’s domain analysis, a method that organizes qualitative data into key thematic areas while preserving the insider perspective of participants. The researchers categorized findings into three broad domains: faculty use of OER, perceived benefits and challenges, and faculty support needs. Themes within each domain were developed from the language and conceptual frameworks expressed by participants themselves, allowing the researchers to interpret not only what faculty said but how their ideas connected within broader patterns of thought and experience.

Coding was carried out independently by at least two members of the research team. A shared codebook was developed and refined collaboratively, ensuring consistency and rigor in the coding process. Any discrepancies in interpretation were resolved through discussion and consensus. NVivo software was used to organize and query the data, although interpretation remained firmly rooted in qualitative, human-led analysis.

To ensure the trustworthiness of the findings, the research team employed multiple strategies, including triangulation of data sources, member checking with participants, reflexive dialogue among team members, and the use of rich, contextualized quotes to support key themes. Rather than seeking statistical generalizability, the study aimed for transferability—providing detailed descriptions that allow readers to assess the relevance of findings within their own institutional and instructional settings.

Finding and Dissemination

The results of the data analysis were organized into thematic findings. These themes emerged inductively during analysis and are presented alongside corresponding visual representations (see Figure 1 for an example). Additionally, each finding is illustrated with compelling faculty anecdotes that offer deeper insight into their lived experiences with OER.

For example, in describing the perceived benefits of using OER, one faculty member shared:

OER to me is freedom, freedom from this push towards the norm. I am not a big fan of having things in locked steps. As the quarter goes on, I am feeling my class, how it is going and I change on the fly. I always felt constrained by the traditional textbook. I also felt constrained by certain pedagogy based on the traditional view of what mathematics classroom is. This freedom from OER gives me new energy, like what can’t I do?

In addition to thematic findings, the analysis produced detailed and actionable recommendations for policymakers and college administrators, extending beyond those aimed at researchers. These recommendations were supported by relevant anecdotes and organized into actionable categories to support implementation.

Conclusion: Turning Method Into Impact

This chapter has presented a comprehensive account of the design and implementation of a statewide, mixed-methods study examining faculty adoption of OER within Washington’s community and technical colleges. By foregrounding methodological transparency alongside empirical findings, this case study contributes a replicable framework for future research that centers faculty perspectives, attends to institutional context, and informs policy development.

References

Chae, B., & Jenkins, M. (2015). A qualitative investigation of faculty open educational resource usage in the Washington Community and Technical College System: Models for support and implementation (Report). Washington State Board for Community & Technical Colleges.

Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. Jossey-Bass.

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Maxwell, J. A. (2013). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Patton, M. Q. (2001). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Spradley, J. P. (1979). The ethnographic interview. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Weiss, C. H. (1979). The many meanings of research utilization. Public Administration Review, 39(5), 426–431.