A Comparison of OER Materials and Traditional Resources in General Chemistry

Sonali Raje

CHEM 131 is the first part of a two-part General Chemistry course sequence at Towson University, a public institution in Maryland. Students take it concurrently with CHEM 131L, the laboratory part of the course, that involves experiential learning. The typical cohort enrollment is about 400-450 students in the Fall and 300-350 in the Spring. The course is a requirement for all chemistry majors. Additionally, several students from other majors also use this course to fulfill a general education requirement for graduation. For several semesters, the course used Pearson’s Mastering as its online learning platform, along with its self-paced learning modules in addition to the associated textbook. The cost ranged between $70-$90 for access to materials for one term. Students were required to pay an additional amount for the second part of the General Chemistry course. To ensure standardization in the curriculum, all faculty teaching the general chemistry courses provide collective input on the course textbook that is adopted. All sections follow identical coverage of topics, the laboratory experiments are the same for the entire cohort and we follow a common syllabus. The final exam is created by all instructors teaching the course.

Rationale for Open Education Resources

At our institution, students have historically struggled in CHEM 131. Our Drop-Fail-Withdraw (DFW) rates are comparable to the national average (approximately 40%). To help students succeed in the course, instructors have used different textbooks from various publishers in addition to various pedagogical strategies to address the high DFW rates for the general chemistry course sequence. Many of these publisher-based learning systems provide a self- paced tutoring model for students by giving them repeated practice on concepts that they answer incorrectly. These learning systems also provide question banks which can be used for online quizzes and for generating practice homework questions. Despite the use of these often- expensive resources, our grades in CHEM 131 remained at a 40% DFW rate. A parallel study from our department has shown a correlation between work-life balance and final exam scores in CHEM 131. Several students in our classes reported an inability to access campus resources like instructor office hours and help sessions or free tutoring on campus, because they had to work to pay for college (Stitzel & Raje, 2022). These issues were compounded by the pandemic, not just at our campus, but nationwide.

Post COVID era, several families faced financial hardships resulting in a drop in college enrollments. Prior research has shown that commercially available textbook costs can be prohibitively expensive for families (Opper, Porter and Aguero, 2022) and a cause of stress for students (Murphy and Rose, 2018). Studies have indicated that the inability to afford course materials results in negative consequences like failing or withdrawing from courses while adding more financial burden due to delayed graduation (Arnaud, 2019; Richard, Cleavenger and Storey, 2014). Other studies on college affordability have indicated that about half of the students enrolled in colleges report food insecurity and a third report housing insecurity (Broton and Goldrick-Rab, 2018). Previous research on the use of open education resources (OER) shows that using these materials potentially enables a 29% reduction on withdrawal from courses (Clinton and Khan, 2019). Brandle et al. (2019) show that students feel relieved of the financial stress when they are able to use zero cost textbooks. In a quantitative study showing student perceptions on the use of OER, Mayer (2023) has shown that course passing rates for students went up by seven percent. As such, using OER for instruction could be one potential way of alleviating the financial burden on families while allowing students to navigate college.

Methodology

OER Adaptation

A survey of multiple chemistry textbooks and conversations with instructors at national and international conferences has shown that the content covered in general chemistry remains consistent across the country. Earlier work that examined how frequently students used textbooks created by for-profit publishing companies versus OER texts have either shown no difference in the usage of textbooks (Jhangiani et al. 2018; Grissett and Huffman, 2019) or greater use of the textbook for the OER text (Cuttler, 2019; Allen, et al., 2015).

In the discipline of chemistry, open access resources are required for lab and lecture. Researchers are currently engaged in creating learner friendly open access content for students in chemistry lab (Carmel et al., 2021). For lecture, in addition to several websites like YouTube and Khan Academy, free online videos (Jackson, 2017) and hyperlinked topic modules (Russay, et al., 2011), there are two main OER texts, Libretexts (earlier ChemWiki) and OpenStax Atoms First. As the OpenStax Atoms First content was closely aligned with the sequence of content coverage in our department, the decision was made to adopt the OpenStax book for the pilot study to determine the efficacy of OER texts.

Participants

All students enrolled in the author’s class for three semesters (Fall 2019, Fall 2021 and Spring 2022) were participants in the study. The pandemic semesters were not included as outliers. The study has received clearance from our institutional review board.

Research Design

As a chemistry education faculty member, the author received an OER Adapt/Adopt mini grant through our Faculty Center for Teaching Excellence (FACET). The pilot OER study was first carried out in Fall 2021, the first semester after the pandemic when instruction was fully in-person. Data analysis was carried out using a quantitative approach, with a combination of student surveys and statistical analyses.

The pilot study addressed the following research question: Is there a difference in student performance between students who use OER materials versus those who use publisher content?

In the first part of the study, pre and post COVID data was compared on the use of publisher generated materials in the Fall 2019 semester versus OER materials Fall 2021, as the primary unit of analysis. Data was not collected in Fall 2020 as it was the first time instruction went virtual. As CHEM 131 is a multi-section course, to ensure that the findings were not limited to one instructional style alone, in Fall 2021, the study was extended to compare data between multiple sections using publisher generated materials and the pilot sections that used OER materials. To triangulate the results, a comparison was also done between publisher materials from the author’s Fall 2019 section and Fall 2021 sections taught by other instructors. To eliminate instructor bias as a confounding variable, course grades across multiple sections were compared to determine the impact of the different types of learning materials on student performance. To ensure reliability in the analysis, the data was collected over multiple semesters. Additionally, a Likert scale survey was given to students to specifically get feedback on the OER content and the utility of the material for learning.

Results and Discussion

As mentioned earlier, faculty teaching general chemistry have used multiple pedagogical strategies to lower the DFW rates. One factor that has been identified early-on as a predictor of success in CHEM 131, were quiz one scores in any given semester. This finding was based on observations over multiple semesters, prior to COVID. Consequently, quiz one scores from the author’s Fall 2019 that used publisher generated materials, were compared to quiz one scores from the author’s pilot Fall 2021 section that used the OER materials. Data was analyzed using a two-sample t-test with independent means. The table below shows the results of the analysis. As seen by the p-values, which are considerably more than 0.05, the difference in scores for the two samples are not significant. This indicated that students using OER materials had comparable scores as those with publisher-generated materials for the first quiz of the semester.

Table 1

| Quiz 1 | N | Mean scores | t(df) value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fall 2019 | 64 | 38.5 | t(103)=0.205 | 0.838 |

| Fall 2021 | 41 | 38.1 | t(101)=0.220 | 0.826 |

Two-sample t-test of independent means for publisher and OER materials pilot study

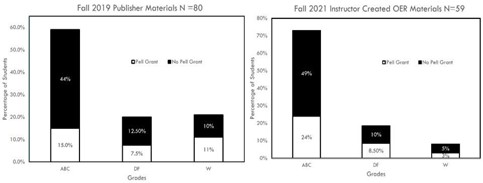

These results were encouraging as we continued to use OER materials for the rest of the semester of the pilot study. Figure 1 shows the grade distributions between the Fall 2019 and Fall 2021 grades for those sections.

End of term exam scores between the pilot section and sections taught using publisher materials show similar outcomes. The passing grades are ‘ABC’, and the failing grades are ‘DF’. The Withdrawals (W) are measured separately based on prior research that shows a lower withdrawal of students when OER materials are used (Clinton and Khan, 2019). The primary reason for comparing students with Pell grants and those without Pell grants was to determine if the accessibility of the free materials would be helpful, as these grants are typically given to students from low-income families.

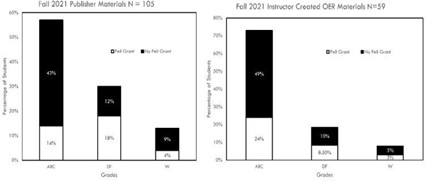

From Figure 1, in the Fall 2021 semester, it appears that the students who use OER materials have a higher passing rate than those who use publisher-generated materials. The withdrawal rates for the section using OER materials is 8% versus 13% for sections using publisher generated paid materials. Pell grantees had passing grades for 24% of the total number of students, whereas the percentage of students with Pell grants who showed passing scores were 14% for the publisher generated materials. The DF rates for students were lower in the OER pilot section as compared to those in sections using publisher materials. These results appear to show that OER materials can be beneficial to students over publisher generated materials.

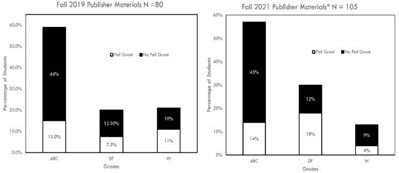

To verify if this was indeed the case, a comparison was made between publisher materials from Fall 2019 (pre-pandemic) and data from sections using publisher materials in Fall 2021 (post-pandemic). Figure 2 shows that the passing grades are comparable between the two terms for students receiving Pell grants as well as those who did not receive those grants. It is to be noted that while the ‘W’ rates were lower in Fall 2021for Pell grant recipients, the ‘DF’ grades were higher than for those in Fall 2019 for that same population.

A comparison of grades in Fall 2021 for publisher materials and the OER pilot section shows similar trends in the passing grades. However, the OER section appears to have lower DF and W grades as compared to the publisher materials users.

While these preliminary results were encouraging and comparable to a study in Turkey (Islim, 2016), we did not see these trends reproducibly over later semesters. A comparison of scores on a common final exam showed similar scores for OER users and those who used publisher materials after the initial results from Fall 2021. These results are consistent with findings from several other studies using OER materials in chemistry (Sansom, Clinton-Lisell and Fischer, 2021; Hilton, 2018; Hilton, 2016), where OER materials are neither better nor worse than traditional publisher created content.

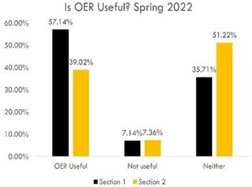

Another aspect of our study involved getting feedback from the population who is directly impacted by the content used for learning: our students. At the end of the semester, all participants enrolled in the course were given a Likert scale survey. Survey questions solicited feedback about the cost affordability of the materials, if students would prefer to pay for publisher resources that would enable students to learn the content better and finally, if using OER content helped facilitate learning. For brevity, only results from a question that asked for overall utility of OER materials are included. Figure 4 shows results from Spring 2022, from two separate CHEM 131 sections. Only about 7% of students did not find the OER materials useful.

Some limitations of OER

During the pandemic, all the instructors teaching the course had developed materials that could help students learn the content. However, some of the publisher content was certainly helpful. The publisher-created textbook and online learning system had some artificial intelligence (AI) materials that allowed students to get repeated practice with some of their content based on their performance. The publisher algorithm presented students questions that were uniquely tailored to their preparation levels and then gave them repeated practice till mastery- this would be almost impossible to replicate using open educational resources. For one thing, OER requires periodic monitoring to ensure that the content being uploaded is accurate and relevant. One of the objectives of the ADAPT/ADOPT OER grant was to disseminate the materials that were created to the bigger Chemistry OER community of practice. In the past, faculty in our department have used some in-house instructor-generated questions on homework help sites like Chegg and Quizlet that students can simply download (Raje and Stitzel, 2020). Instructors perceive the time and effort to develop OER materials as the biggest barrier to using these materials (Belikov and Bodily, 2016), Similar observations were seen in other studies where faculty displayed reluctance to dedicating time and effort to improve teaching and learning when it may not be a priority over research and securing extra-mural funding at various institutions (Walczyk et.al. 2007; Todoriniva & Wilkinson, 2020).

Conclusions

As mentioned above, our results were comparable to previous work carried out by other researchers studying the efficacy of OER in introductory chemistry courses. Even though OER materials do not seem to improve student performance, our findings consistently showed that students who used OER materials perform just as well as students who used publisher-generated materials. Consequently, we stopped using publisher generated materials completely in Fall 2023 and switched to using OER for the entire general chemistry cohort and both parts of the two-part sequence (CHEM 131 and CHEM 132; N = 59 for pilot in Fall 2021to N > 400 cohort-wide per semester). The number of students who took CHEM 131 and 132 from Fall 2023 through Fall 2024 (three semesters) is as follows: CHEM 131 (General Chemistry I) = 1049 students (CHEM 132 (General Chemistry II) = 581 students. Using the lower bound of the textbook cost of $70 per student per semester, we have found a cost savings of $66,087 for CHEM 131 students and $36,603 for CHEM 132 students from Fall 2023 through Fall 2024, without compromising on student performance compared to more expensive materials.

Although our findings suggest that using OER materials do not provide additional gains in student grades, the scores are comparable to those that students obtain through publisher generated materials. For future work, we intend to couple our current OER resources with AI generated materials from various sources to supplement student learning that was earlier available through publisher created materials. This would enable us to provide students with a no-cost resource that could supplement the deficit that paid publisher generated materials could provide, before the advent of integrative AI.

References

- Allen, G.; Guzman-Alvarez, A.; Smith, A.; Gamage, A.; Molinaro, M.; Larsen, D. S.(2015). Evaluating the Effectiveness of the Open-Access ChemWiki Resource as a replacement for traditional General Chemistry textbooks. Chemistry Education Research and Practice. 16 (4), 939−948.

- Arnaud, C. H. (2019). Open-Access Textbooks Move Ahead. Chemical Engineering News, 7 (11), 20−22.

- Belikov, O. M.; Bodily, R. (2016). Incentives and Barriers to OER Adoption: A Qualitative Analysis of Faculty Perceptions. Open Praxis, 8 (3), 235−246.

- Brandle, S.; Katz, S.; Hays, A.; Beth, A.; Cooney, C.; DiSanto, J.; Miles, L.; Morrison, A. (2019). But What do the Students Think: Results of the CUNY Cross-Campus Zero-Textbook Cost Student Survey. Open Praxis, 11 (1), 85−101.

- Broton, K. M.; Goldrick-Rab, S. (2018). Going without: An exploration of food and housing insecurity among undergraduates. Educational Researcher, 47 (2), 121−133.

- Clinton, V.; Khan, S. (2019). Efficacy of Open Textbook Adoption on Learning Performance and Course Withdrawal Rates: A Meta-Analysis. AERA Open, 5 (3), 1−20.

- Carmel, V., Maillard, M-N., Descharles, N., Le Roux, E., Cladière, M. Billault, I. (2021). Open Digital Educational Resources for Self-Training Chemistry Lab Safety Rules. Journal of Chemical Education, 98, 1, 208-217.

- Cuttler, C. (2019). Students’ Use and Perceptions of the Relevance and Quality of Open Textbooks Compared to Traditional Textbooks in Online and Traditional Classroom Environments. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 18 (1), 65−83.

- Grissett, J. O.; Huffman, C. (2019). An Open Versus Traditional Psychology Textbook: Student Performance, Perceptions, and Use. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 18 (1), 21−35.

- Hilton, J. (2016). Open Educational Resources and College Textbook Choices: A Review of Research on Efficacy and Perceptions. Educational Technology Research and Development, 64 (4), 573−590.

- Hilton, J. (2018). A Synthesis of Research on OER Efficacy and Perceptions Published between September 2015−2018. Paper Presented at the 15th Annual Open Education Conference; Niagara Falls, NY.

- Islim, O.F. (2016). The Impact of OER on Instructional Effectiveness: A Case Study. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science & Technology Education, 2016, 12(3), 559-567

- Jackson, D. M. (2017). Establishing an Instructor YouTube Channel as an Open Educational Resource (OER) Supplementing General and Organic Chemistry Courses. In Teaching and the Internet: The Application of Web Apps, Networking, and Online Tech for Chemistry Education; Christiansen, M. A., Weber, J. M., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC; pp 115−135.

- Jhangiani, R. S.; Dastur, F. N.; Le Grand, R.; Penner, K. (2018) As Good or Better than Commercial Textbooks: Students’ Perceptions and Outcomes from Using Open Digital and Open Print Textbooks. Canadian Journal on the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 9 (1), 1−22

- Mayer, J. (2023). Open Educational Resources (OER) Efficacy and Experiences: A Mixed Methods Study. University Libraries Publications. 23, 4 pp. 773-798.

- Murphy, L.; Rose, D. (2018). Are private universities exempt from student concerns about textbook costs? A survey of students at American University. Open Praxis, 10 (3), 289−303.

- Opper, J., Porter, M.K., Aguero, D.B. (2022) Florida Virtual Campus. Florida Student Textbook Survey; Florida Virtual Campus: Tallahassee, FL

- Richard, B.; Cleavenger, D.; Storey, V. The Buy-In: A Qualitative Investigation of the Textbook Purchase Decision. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice 2014, 14 (3), 20−31.

- Raje, S., Stitzel, S. (2020). Strategies for effective assessments while ensuring academic integrity in general chemistry courses during COVID. Journal of Chemical Education, 97, 9, 3436-3440.

- Russay, R. J.; McCombs, M. R.; Barkovich, M. J.; Larsen, D. S. (2011). Enhancing Undergraduate Chemistry Education with the Online Dynamic ChemWiki Resource. J. Chem. Educ. 88 (6), 840.

- Sansom, R.L., Clinton-Lisell, V., Fischer, L. (2021). Let Students Choose: Examining the Impact of Open Educational Resources on Performance in General Chemistry. Journal of Chemical Education, 98, 745-755.

- Stitzel, S., Raje S. (2022). “Understanding diverse needs and access to resources for student success in an introductory college chemistry course”. Journal of Chemical Education, 99, 1, 49-55.

- Todorinova, L.; Wilkinson, T. D. (2020). Incentivizing faculty for open educational resources (OER) adoption and open textbook authoring. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 46 (6), 102220. (80) CAST. Universal Design for Learning Guidelines.

- Walczyk, J. J.; Ramsey, L. L.; Zha, P. (2007). Obstacles to instructional innovation according to college science and mathematics faculty. Journal Research in Science Teaching, 44 (1), 85−106.