12 Hidden Student Populations: Third-Culture Kids

Rebecca Krouse

Prior to this semester, I had never heard the term “Third Culture Kid.” Initially when I heard this, I thought of third world, or third world country. I soon learned that the concept of the TCK is something much more abstract and complex. Those who experience their developmental years abroad may be thought of as privileged. Who wouldn’t want to travel the world with their families? The opportunity to see other countries and immerse yourself in other cultures sounds like a dream, right? Although there is much debate concerning whether the life of TCKs is positive or negative, I think the focus should be on how their experiences can adversely affect their mental health. Many will experience depression and anxiety and repatriation and transitioning to college will bring even more stress onto them. Higher education practitioners should work to implement support programs specific to their unique needs.

Third Culture Kids’ Integration within Higher Education

College can be an exciting time for multiple opportunities, new friends, and a newfound freedom to be oneself. It can also be quite stressful. The transition from high school to college can be difficult for many students, especially those who may not be going to a school close to home. Furthermore, the concept of “home” might be too abstract to define for some students. Some of the incoming freshmen stepping onto campus next fall may have spent a great deal of their young lives living overseas. These students are known as Third Culture Kids, or TCKs, and their experience is unique because they have had a different upbringing from their peers who grew up in a static and stable environment. Many TCKs experience issues with identity, depression and anxiety, and social engagement. Higher education institutions should consider designing a program to cater to the specific needs of this student population. To better prepare them for the transition to college and the repatriation to their passport country, or the country where they were born, they should provide resources from the time the student applies to college to the time they graduate. Support should be ongoing and readily available. Four major areas to consider implementing support are the application process, campus counseling services, campus living, and campus organizations.

Application Process

When students apply to college, they are required to fill out multiple forms, many with personal, identifying information such as gender identity, ethnic background, and educational history. The application process could potentially allow colleges to flag incoming submissions from students who are potential TCKs. They could ask more detailed questions regarding where the student has lived throughout their lives. A question as simple as “Have you ever lived outside of the US for more than 3 years” could allow colleges to reach out to applicants who respond affirmatively with more information about available resources. These resources could also be published on the university website for potential applicants to view when considering where to apply. Schools with specialized programs designed to support TCKs could also be a way for institutions to recruit prospective students.

Repatriation

Like most of the other incoming students, TCKs experience the same traditional student development tasks that their peers experience, but they also go through the process of repatriation into their passport country while attempting to navigate cultural shock (Kortegast and Yount, 2016). They are often referred to on campus as “hidden immigrants” because their citizenship status often hides their personal experiences living abroad. They also tend to be thought of as privileged, therefore drawing attention further away from their specific needs within higher education (Kortegast and Yount, 2016). Due to their assumed privilege, many would not consider how these students may need additional support during the transition into college while also repatriating to their passport country. They may not have their families physically there with them to support them, which can cause them to grieve and cope with feelings of loss, creating and piling even more stress onto them while in college (Kortegast and Yount, 2016). They may also feel pressured to succeed and to not fail. Crossman (2016) notes that many TCKs will experience the four stages of starting again: isolation, investment, enjoyment, and settling. If colleges could design a program to assist students through these four stages, then they could potentially shorten the time it takes for students to get through the rough phase of isolation.

Academic Expectations

The college experience of TCKs is unique for many reasons, but one of the most important ones to consider when discussing how to frame means to support them is how they often feel as though they must live up to a certain standard. Many come from families with parents who work for embassies, mission organizations, or international corporations (Crossman, 2016). These students often believe their academic performance is a direct reflection of their parents and thus they do not wish to disappoint them. When they arrive at college, they need a support network in place, ready to assist them throughout the course of their academic journeys.

Loss of Identity

When other students ask them simple questions such as “Where are you from” or “Where does your family live,” they can trigger feelings of isolation, anxiety, and self-doubt (Crossman, 2016). When TCKs come to college, they often must leave virtually everything they know behind. The cultural differences can be difficult to adjust to and they can struggle with their personal sense of identity. The concept of “home” may feel unstable, and many may redefine what “home” means to them over time (Kortegast and Yount, 2016). These feelings of uncertainty can add unnecessary stress, leading to anxiety and depression. This could stem from the first stage of starting again, isolation, as noted by Crossman (2016). Institutions should consider developing specialized counseling services for TCKs to ensure them that while they may feel isolated or disconnected from their peers, they are not alone.

Campus Counseling Services

Smith and Kearney (2016) note that “TCKs are a large and rapidly growing demographic in global society and yet one that is mostly invisible and unsupported on US college campuses” (p. 958). Campus counselors could benefit from learning more about TCKs and their unique college experience to better serve them in their mental health needs. Ensuring these students that they are supported and that their feelings are valid could help take some of the stress off them while also allowing them to express their emotions, which can reduce anxiety and depression.

On-Campus Housing

One potential way for institutions to support TCKs in their learning journeys is to provide a unique on-campus living experience. When TCKs attend international schools overseas, they are often in classes with many other students like themselves from all over the globe. Colleges should consider working with their on-campus housing to design a specific dorm that is reserved for TCKs as well as international students. This could potentially allow them to feel more comfortable while at school because they would be in the company of other students with similar backgrounds. These dorms should also allow students to remain on campus during breaks if they do not have anywhere to go for the holidays. While TCKs are not categorized as international students within their campus student population, their cultural development is quite different from their American peers. Rooming TCKs with each other or with international students creates a special environment for these students to interact with others who will understand them better than students who were grew up in the US. It is essential for institutions to encourage them to make new friends and get involved with their peers.

Many TCKs who fail to establish connections do not feel as though they belong, and they may transfer several times or drop out of school altogether (Smith and Kearney, 2016). By allowing them to room with other students with similar backgrounds, these specialized dorms could potentially allow them to establish friendships early on, enabling them to form a sense of belonging, making it more likely that the students will acquire long-term success (Smith and Kearney, 2016). Another way for institutions to support TCKs is by partnering with on-campus organizations to provide additional resources that they may need during their academic careers.

On-Campus Organizations

Many campuses have International Student Organizations that host events for students like social mixers, cultural nights, international dinners, and more. Institutions should consider working with these on-campus organizations to develop specialized programs that cater to the unique lived experiences of TCKs. These students should be contacted by organizations to inform them of available resources as well as upcoming events. On-campus involvement is a great way for students to develop a sense of belonging and a sense of pride within their campus communities. On-campus organizations can also provide a sense of family for those who may be far away from their parents or relatives. They could host holiday dinners to ensure that every student has a place to go on days like Thanksgiving or Christmas, or they could create a network of local host families to welcome students over for dinners or holiday gatherings. Organizations could send welcome emails to incoming students during the application process to give them enough time to learn more about the organization’s mission statements and how they aim to support this student population and their specific needs within higher education.

Assessment

On-campus housing, counseling services, and organizations that aim to assist TCKs should keep records for those that utilize their services. There is a need for further research concerning this population and how to better serve them. Assessment projects to analyze and record the effectiveness of support programs for TCKs could potentially provide higher education practitioners with means to improve upon their programs.

College can be stressful and intimidating for many incoming students, but for TCKs who are also navigating repatriation while coping with the separation from their parents and families, it can be even more difficult to adjust. This student population is unique because while they are categorized with their passport countries, they may not feel culturally connected. They are one of the most underserved and under researched student populations, and they often struggle with anxiety, depression, and with their sense of identity. Higher education institutions should consider developing specialized resources and programs to assist these students by flagging potential TCKs during the application process, providing specialized counseling services with culturally educated mental health professionals, offering priority dorm assignments for TCKs and international students, and circulating initial welcome packets from on-campus organizations such as International Student Associations to TCKs via email at the start of the academic year. Providing these students with resources to address their specific needs can allow them to feel a better sense of belonging while in school, which can ultimately allow them to remain enrolled and to see their degrees to completion.

References

Crossman, T. (2016). Misunderstood: The Impact of Growing up Overseas in the 21st Century. Summertime Publishing.

Kortegast, C. & Yount, E.M. (2016). Identity, family, and faith: U.S. Third Culture Kids transition to college. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 53(2), 230-242. ISSN: 1949-6591 (print)/1949-6605 (online)

Smith, V.J. & Kearney, K.S. (2016). A qualitative exploitation of the repatriation experiences of US Third Culture Kids in college. Journal of College Student Development, 57(8), 958-972. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2016.0093

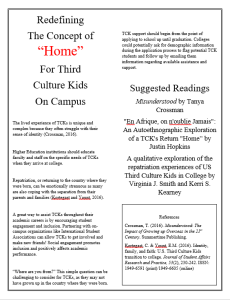

Third-Culture Kids Informational Handout

In addition to the applications and considerations paper for this course, we also designed handouts with useful information and available on-campus resources regarding third-culture kids and their unique experiences within higher education.

ACPA and NASPA (2015) Competency Statement:

Advising and supporting seems like the best competency to apply to the course concerning the lived experience of Third Culture Kids. TCKs often have trouble with the transition from secondary education to higher education and they may need additional support to help them adjust to college life.