The Division of Institutional Diversity as an Organization within Oklahoma State University

Oklahoma State University (OSU) is a public land-grant university in Stillwater, Oklahoma that houses 10 colleges and six divisions. A large institution such as OSU, with more than 35,000 students across its five campuses, must be well-organized to function smoothly and successfully (“About OSU – Oklahoma State University,” n.d.). Nearly half of generation Z students come from racially and ethnically diverse backgrounds and 59% of 18- to 20-year-olds are pursuing a college degree post high school (Fry & Parker, 2018). At a time when higher education is seeing such a change in student demographics, efforts focused on diversity and inclusion on campus must be university-wide beyond the capacities of a single Chief Diversity Officer, or Office for Diversity and Inclusion as seen on most campuses. Therefore, to be successful in this endeavor, institutional leaders must critically consider, recognize, and address various power structures that exist within their university. An in-depth analysis of the structures, functions, and purposes of organizations within OSU, such as the Division of Institutional Diversity (DIVR), specifically the TRiO Department and Diversity Academic Support (DAS), can assist leaders in identifying the ways in which OSU can successfully meet this challenge beyond current successes. An analysis of the entire DIVR is beyond the scope of this paper.

To this end, this paper serves as platform to first analyze the DIVR and identify the challenges faced by members within the organization in engaging with their mission. Secondly, applying theoretical frameworks will allow for analyzing these challenges from various perspectives of the organization as a unit within the larger university. Finally, the appreciative inquiry framework will help leaders address these concerns to further the institution’s mission for diversity and inclusion.

The DIVR within OSU is comprised of the Office of Multicultural Affairs, TRiO Department, DAS and leads the Oklahoma Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation (OK-LSAMP) in Oklahoma. An exploration of the ways in which this division has developed and interacts within their unit, the larger university, and the university community is crucial to fully understand the dynamics within this higher education organization. An analysis of the structure of the organization, and its role within OSU serves this exploration. Such an understanding informs organizational members of challenges faced by all their constituents in fulfilling their mission and promoting organizational change successfully.

Division of Institutional Diversity

History, Mission and Purpose

A Vice President and an administrative assistant originally led the Division of Institutional Diversity. In 2006, Vice President Dr. Cordell Wilson expanded the division with the inclusion of the Office of Multicultural Affairs from Student Affairs, and TRiO Department from the Office of Scholarships and Financial Aid (J. Dew, personal communication, June 27, 2019). Currently, this division has grown to include the DAS along with an expansion of the TRiO programs including the McNair Scholars Program, Upward Bound, and Educational Talent Search (“Diversity Academic Support/TRIO,” n.d.). The division also leads the state of Oklahoma in OK-LSAMP and manages the National Science Foundation’s grant that funds the initiative. The OK-LSAMP is a consortium of Oklahoma colleges and universities focused on developing “programs aimed at increasing the number of students from under-represented populations who receive degrees in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) disciplines” (“OK-LSAMP,” n.d.).

The primary mission of the DIVR is “to develop and support efforts that help the Oklahoma State University System achieve and maintain environments, where all members are actively broadening their perspectives about differences; actively seeking to know individuals; actively including all members of the community in every aspect of the organization; and where students achieve academic excellence” (“Mission,” n.d.). The mission of the DAS and the TRiO Program within the DIVR “is to provide resources and opportunities for academic, social, and emotional growth” (“Diversity Academic Support/TRIO,” n.d.). The Assistant Vice President of DAS and Director of TRiO Dr. Jovette Dew stated that her personal mission through her roles within the Division is “to see students succeed” (Personal communication, June 27, 2019). It is essential to note the ways in which individual leaders within an organization may bring their own motivations and personal missions to add value to the core mission of the division and the university of which they are a part. Delving deeper into the impact and dynamics of various units and their leaders within the division necessitates the examination of the current organizational structure.

Current Structure

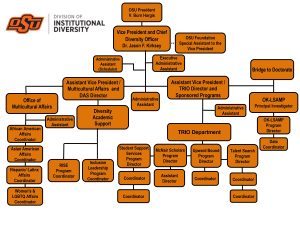

The structure of an organization is reflective of the ways in which an organization intentionally prioritizes the workflow, functions, and processes within itself. Figure 1 details the organizational structure of the DIVR. The Vice President of the DIVR Dr. Jason Kirksey reports directly to the OSU President Burns Hargis. The Associate Vice President Dr. Precious Elmore-Sanders reports directly to the Vice President and serves as the Director of the Office of Multicultural Affairs. In this role, Dr. Elmore-Sanders also oversees the OK-LSAMP. The Assistant Vice President Dr. Jovette Dew reports to the Associate Vice President while serving as the Director for the TRiO Department and Diversity Academic Support. The TRiO Department houses various federally-funded programs including Student Support Services, McNair Scholars, Upward Bound and Educational Talent Search. Coordinators play a crucial role within these programs in student development towards goal attainment. The Diversity Academic Support houses the Retention Initiative for Student Excellence (RISE) and the Inclusion Leadership Program (ILP) funded primarily by donors and companies such as Philips 66.

The federal Department of Education funds the different programs offered through the TRiO Department whose purpose is to advance the educational goals of all program participants. Each of these programs achieves this through different means. For instance, Upward Bound is a program focused on preparing high school students for college success. The McNair Scholars program supports students for a span of 10 years from their sophomore year through attainment of a terminal degree like a PhD or EdD (J. Dew, personal communication, June 27, 2019). The DAS focuses primarily on supporting individuals who wish to “create an inclusively diverse community of learners at OSU” (“Diversity Academic Support/TRIO,” n.d.). The successes of these programs within the DIVR are heavily reliant on the support of OSU as an institution.

Context Within OSU

Many higher education institutions have hired a chief diversity officer to address concerns regarding a lack of inclusivity on campus but do not offer the financial and structural support across the university to make these efforts successful (Brown, 2016). At OSU however, the DIVR and its leadership obtain support behind the scenes in crucial ways from the Office of the President (J. Dew, personal communication, June 27, 2019). There is a focus from the top down across colleges in hiring faculty of color and providing resources to support them resulting in a 53% increase in faculty of color being hired since Fall 2010 (“OSU Diversity Highlights,” n.d.). Such hiring and faculty engagement practices increase students’ sense of belonging as they interact with faculty who look like them and have had similar experiences (Quaye & Harper, 2015).

The DIVR also received structural support in the form of the OSU Inclusive Excellence Wall, Veterans Success Center, Center for Sovereign Nations, and through the DIVR Capital Campaign that raised $3.95 million since 2014 with 36 new endowed scholarships (“OSU Diversity Highlights,” n.d.). Additionally, Diverse Issues in Higher Education ranked OSU within the Top 100 Degree producers for African American, American Indian, Asian American, Latino, and biracial/multiracial graduates (2014-2017) (“OSU Diversity Highlights,” n.d.). While the DIVR has made significant progress within OSU with the support of the larger university leadership, they face multiple challenges in advancing their mission. Some of these are detailed next.

Challenges

Location. As a division focused on helping underrepresented students succeed, the biggest challenge faced by the TRiO Department and DAS is their current physical location (J. Dew, personal communication, June 27, 2019). Students spend most of their time outside the classrooms in the Student Union or the Edmond Low Library located centrally on campus. The DIVR office is located in Scott Hall, approximately a quarter mile west from the central campus. The students who participate in the various programs within DIVR, while provided a few study areas and writing labs within Scott Hall, do not have the additional resources provided by the larger university. These students are also advised by their coordinators within DIVR before meeting with their college advisers. These coordinators focus on “intentional and intrusive advising” to ensure that their students will succeed in obtaining their degree (J. Dew, personal communication, June 27, 2019). Being removed from an accessible central location and unable to meet with students where they typically spend time outside of the classroom, hampers the ability of DIVR staff to successfully assist more students. These students have multiple intersecting identities and must be able to develop holistically by exploring and engaging their identities with various levels of salience. In line with this philosophy, the Office of Multicultural Affairs is located in the Student Union to be accessible to their students. However, TRiO and DAS remain with DIVR in Scott Hall. This tends to further exclude these underrepresented students from the benefits of engaging in High Impact Practices that increase persistence and retention (Kuh, 2015).

Funding Uncertainty. Due to the structure of the division and different types of funding for programs offered to students through the DIVR, there is uncertainty regarding the levels of funding (J. Dew, personal communication, June 27, 2019). State funding may change every fiscal cycle and is limited in its use. Donor funds are less restrictive in their use but require focused fund-raising efforts by executive leadership. For instance, students from these programs are first-generation college students from low socio-economic backgrounds. Federal funds from TRiO programs support their academic needs such as the purchase of stationery. However, when these students attend a conference, or go to internship interviews, federal or state dollars cannot be spent on purchasing or renting interview attire or luggage for travel. These students rely on donor funds for such needs.

The division currently has only seven coordinators between their TRiO programs and DAS to advise their students. The primary role of these coordinators is to help the students plan and prepare for academic success. In addition to being unable to meet with students at a central campus location, the adviser to student ratio is currently insufficient to adequately support all students. Furthermore, members of the DIVR invest time and resources in teaching Diversity courses, a General Education core requirement for undergraduate students at OSU. Since the DIVR is not a college, the courses are housed under the College of Arts and Sciences (CAS). Any income generated from these courses remain with the CAS.

Leaders can use organizational theories to inform their practice in addressing such challenges by viewing higher education as an organization. Student affairs professionals who use theoretical frameworks obtain multiple perspectives into an organization in ways that can stage the division’s priorities, offer ways to achieve their goals, and move the organization forward within the university. Some of the organizational theories that can help analyze the challenges faced by the DIVR include the cultural or symbolic framework and the collegial or human resource framework. Each of these frameworks provide a different perspective, has their own strengths and weaknesses, and can therefore provide holistic solutions and creative ways to address organizational challenges faced by the DIVR. To this end, in the next section, the DIVR is analyzed through these frameworks.

Organizational Analysis

The value of using theory to analyze organizations is expounded with a multi-modal approach. However, some theories may fit certain organizations better than others. A successful analysis of an organization then requires such a multimodal approach while also understanding those characteristics and assumptions of theories that may not represent the organization.

The Cultural or Symbolic Framework

Higher education organizations have a set of core values and assumptions that dictate their historical structures, policies, procedures and mission (Manning, 2018). This culture is situated in the context of the institution’s “history, past players and tradition” (Manning, 2018, p. 71). These institutions have a unified institutional culture or organizational saga, with subcultures within their units and various symbols that are used to promote the culture. As part of promoting the culture, institutions use a variety of symbols, language, stories of heroes and rituals. Storytelling and the use of cultural symbols are intended to unify and engage students and the community in the culture of the institution. All organizational members, while they have their own subcultures within their colleges and divisions, continue to play a role in shaping the institutional culture by giving meaning to these symbols (Manning, 2018). These symbols are socially constructed by members of the institution over time and their meanings are passed on to new members of the institution.

In viewing organizations as cultures, it is important to recognize that symbols remain the same, and new members are taught “the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems” (Schein, 1992, p. 12). This perspective highlights the importance of culture, symbols and the meanings associated with them that have “accumulated over time to shape an organization’s identity and character” (Bolman & Deal, 2017, p. 263). For OSU, such an organizational saga could be represented in our “Cowboy Family” philosophy. Symbols include Pistol Pete, a white American cowboy with guns firing, the university mascot, the slogan “Go Pokes”, the hand gestures that accompany it, and homecoming rituals during games with the sea of orange, the color of the school’s branding. Such cultural symbols based on the history of events and places in Oklahoma may invariably exclude underrepresented populations.

The cultural framework when used as a tool to analyze the DIVR, sheds light on some of their challenges. Organizational structure, through the symbolic framework can be viewed as a theater (Bolman & Deal, 2017). The rituals, symbols, and traditions take place on the center stage. Students from historically underrepresented populations who are a part of TRiO and DAS may not see themselves represented in these stories, symbols, and culture within the OSU saga. They may not be able to participate in various campus traditions due to other academic priorities to maintain academic and program eligibility. The offices of their advisors and computer or writing labs from the DIVR located away from the center of campus life further alienates them from the organizational culture. They may therefore be far removed from the center stage affecting their academic and social engagement.

This framework also suggests that the structure of an organization reflects its history, symbols, and culture over time. This informs the other challenge faced by DIVR, uncertain funding. The lack of dedicated resources may be a result of the DIVR serving student populations that do not fit the stories, cultures, and symbols of the university. If the purpose and mission of the DIVR were central to the mission and saga of the institution, the DIVR would be brought to the center stage. The stories of the constituents of the DIVR would be incorporated into the larger university. The mission of the entire organization would include a renewed focus of a diverse and inclusive “Cowboy Family”. Such a restructuring will allow for increased and dedicated financial support for the DIVR as with other divisions on campus that are a crucial part of the organizational culture, such as the colleges, student affairs and academic affairs. OSU may highlight certain aspects of diversity well as seen in its housing of the Office of Multicultural Affairs and the showcasing of Diversity Awards within the central area of the campus. However, it is crucial to carry these efforts forward to be inclusive of all types of diversity including the lower SES, mostly first-generation, students of color who form the majority of the TRiO program and DAS participants.

The cultural or symbolic framework offers new ways to look at the challenges facing the DIVR. However, it does not offer insight into collaborations between the DIVR and the various colleges of which students are a part. The DIVR advises TRiO and DAS students before they meet their academic advisers within their respective colleges and offer diversity courses in conjunction with the CAS (J. Dew, personal communication, June 27, 2019). The collegial framework serves as a tool to explore such collaborations and reframe the challenges faced by the DIVR.

The Collegial or Human Resource Framework

The collegial or human resource framework describes the collaborative relationship between groups, societies, and communities and their organizations as a function of their respective needs and roles within the organization (Bolman & Deal, 2017; Manning, 2018). This framework assumes a flat structure to the organization and treats constituents as independent, capable and autonomous (Manning, 2018). The structure applied to the organization through this lens tends to be circular and fosters collaboration and improves group dynamics (Bolman & Deal, 2017). This framework shares power among peers and is conducive for consensus building.

This framework, when applied to the DIVR, stages the leadership and staff as peers of the faculty within various colleges within OSU. It positions them in a collaborative environment to promote a culture of diversity and inclusion and obtain faculty support in their mission. For instance, faculty members need the support and guidance of the members of the DIVR during grant writing and letters of the impact on the diverse constituents within OSU (J. Dew, personal communication, June 27, 2019). The DIVR members require the support and engagement of faculty in their diversity and inclusion mission in hiring practices and student support. Being collegial allows for mutual growth and collaboration.

The collegial or human resource framework also addresses the uncertain funding challenge faced by the DIVR. Building relationships with faculty and staff in the colleges allows faculty to be more engaged in diversity issues in the curriculum. A collaborative approach could result in a revenue sharing model for teaching diversity courses in ways that are more financially sustainable for the DIVR. This in turn fosters the ability of colleges to be increasingly inclusive in their curriculum and ways of teaching. These collaborations also allow advisors in the DIVR to communicate freely with the advisors in the colleges providing the best support and guidance for the success of underrepresented student populations. Collegiality can also support fundraising efforts of the DIVR leadership.

The collegial or human resource framework, however, does not provide a complete analysis of the DIVR in consideration of the organizational structure within the division. While the directors and coordinators of the DIVR can work collaboratively with members across the university, they are still part of a structural hierarchy reporting to the Vice President who in turn reports to the president. Some collaborations, therefore, may not be encouraged due to political factors, competition for resources, and conflicting priorities. Additionally, the collegial or human resource framework offers a way to approach some of the contributing factors of the funding challenge faced by the DIVR. However, it does not provide insight into the challenge of location. The ability to use multiple frameworks in analyzing an organization is therefore crucial. Different frameworks offer different perspectives that can help organizations look at their challenges differently and come up with creative ways to solve them.

The mission and purpose of the DIVR must be structurally and symbolically central to the mission of the university. The cultural or symbolic framework could engender the current culture of the organization be more inclusive of the underrepresented voices by creating a multicultural view focused on equitable outcomes. OSU must invest in their stories, symbols, and language use to be inclusive and create sustainable and lasting change. The collegial or human resource framework highlights the importance of collaborations and relationships between the DIVR and constituents of the university. Taken together, for lasting change to take place, and centralizing diversity and inclusion at OSU, these frameworks situate culture and collegiality as most critical. Additionally, applying the appreciative inquiry (AI) framework can further assist in increasing the current successes of the DIVR in fostering the development of a larger diverse student population.

Appreciative Inquiry in Practice/Applying Appreciative Inquiry

In a higher education organization like DIVR, creating a collaborative and appreciative environment can lead to successful operations and sustained impact on diverse student populations. The AI framework serves as a tool that incorporates multiple diverse voices collaboratively in an environment that is engaged in the “positive core” (Cockell & McArthur-Blair, 2012, p. 13) surrounding those elements that work within an organization. Through this process, organizations can “heighten energy, sharpen vision, and inspire action for change” (Cockell & McArthur-Blair, 2012, p. 13).

5-D Model

The AI process guides groups through a 5-D model. This consists of defining the positive focus of inquiry, discovering what works within their organization, dreaming of an ideal future together using images and storytelling, designing various strategies and plans to make their preferred future happen, and delivering results as their organizational destiny (Cockell & McArthur-Blair, 2012).

The AI framework offers an open and creative way to construct an appreciative climate. It allows for collaborative processes that intentionally pull together different groups of people towards promoting positive change for the future (Cockell & McArthur-Blair, 2012). Through the application of AI, institutions can focus on developing those elements that function well and mobilizing groups to action (Cockell & McArthur-Blair, 2012). The success of such an application relies on authenticity and interconnectedness, and the co-constructed practice requires participants being present and engaged in the process (Cockell & McArthur-Blair, 2012). This is crucial in providing a platform for diverse views and ideas informed by participants’ stocks of knowledge and social location through narratives and storytelling and reduces the perpetuation of hegemonic norms. The application of AI to the DIVR addresses the challenges facing the organization. It can inform practice, encourage collaboration, and position the DIVR for success in its mission. The next section serves as a platform to explore the application of the AI framework.

Application

The 5D model of the AI framework consists of definition, discovery, dream, design, and destiny. The definition process involves choosing a positive aspect of the organization and its success as the focus of the inquiry. This process appreciates and values the best of the organization at the present moment (Cockell & McArthur-Blair, 2012). For the DIVR, the definition process would be grounded in their successes with diversity efforts across campus. Their focus of inquiry could be “Diversity at its best”. The discovery process requires identifying the factors that give an organization its life or success; appreciating and valuing the best of what currently works (Cockell & McArthur-Blair, 2012). In considering the DIVR, interviews and conversations with their team members would likely lead to recognizing their storytelling and narratives. The accolades and records including the diversity numbers and rankings, success stories of their students, along with national recognition would become apparent. Additionally, the efforts of the exceptional staff composed of coordinators and program directors who are focused on intentional and intrusive advising towards student success would be revealed as a major aspect of the DIVR’s success.

The next process is the dream focusing on envisioning a future through visual and word images (Cockell & McArthur-Blair, 2012). This process will allow DIVR to envision themselves as a larger team supportive more students through increased TRiO programs. Engaging in multiple programs will increase their operational funding. The dream process will allow the staff to envision an office that is accessible, positioning them in a location central to student life and closer to colleges and departmental faculty, fostering collaboration.

In the design process, strategies and action plans are co-constructed with all the participants with a focus on “provocative propositions…and ways to make it happen” (Cockell & McArthur-Blair, 2012, p. 29). When the AI group includes faculty members, administrators and student representatives, propositions could include ways to collaborate that are mutually beneficial. Faculty members may be able to work out ideas to teach diversity courses, incorporate diversity modules in their current teaching, and design incentives to increase the adoption of best pedagogical practices for teaching diversity across campus. Working with administrators might highlight opportunities for revenue-sharing and in the creation of efficiencies in the utilization of space allowing for effective restructuring to make room for DIVR within the central parts of campus. Different perspectives and the various bodies of institutional knowledge of those involved will allow for new ideas and plans to effect change.

Finally, the destiny process is the delivery phase where action plans are executed. The DIVR may test out a new model for their course offerings and they ways in which they collaborate with the colleges on campus. Restructuring of office spaces and its subsequent functionality will be tested. Various collaborative fundraising efforts may come to pass. This process results in an emergent design where action plans must continually go through the 5D processes as change happens until the DIVR has achieved its preferred future (Cockell & McArthur-Blair, 2012).

Engaging in AI will empower and allow the DIVR to learn, adjust and improvise as they initiate additional TRiO programs, increase their funding, centralize their campus location, and impact more student lives. To this end, the DIVR can address their challenges of location and funding by pursuing the recommendations listed in the next section as informed by the AI framework.

Recommendations

The primary challenges faced by the DIVR is their location away from the central campus, and uncertain and restrictive nature of their funding. The 5-D Model process of the AI framework highlights the strength of the DIVR in its people. The AI framework suggests an approach that focuses on engaging in the strengths of the organization and building the desired future through such a process. This approach focuses less on aspects of the organization that are broken. Instead, it refocuses the efforts of those within the organization on those things that can be enacted more, to begin to act toward the envisioned future (Cockell & McArthur-Blair, 2012).

The principles of constructionist, simultaneity, poetic, anticipatory, positive, awareness, narrative, wholeness, enactment and free choice form the basis of the AI process (Cockell & McArthur-Blair, 2012). Based on the constructionist principle, co-constructing the culture and realities of diversity on campus by using the language of inclusion across all divisions and colleges of OSU is essential. According to the simultaneity principle, asking the right questions begins the process of change. DIVR could begin by asking the Board of Regents, Office of the President, Vice Presidents and Provost, and the College Deans about the importance of diversity and inclusion within their areas of purview. The DIVR can position the impact of diversity and inclusion efforts on campus as crucial to the university goals and highlight the negative impact of the remoteness of their location on the students in the DIVR programs.

The poetic principle informs the DIVR to focus on creative and collaborative ways to address their challenges. The DIVR could rely on their strengths—their staff—to meet with students for appointments at central locations or collaborate with colleges to utilize designated student study areas for appointments. Per the anticipatory principle, the DIVR must visualize the positives to be able to envision and act positively in their planning. Focusing on their storytelling and sharing the positive successes across the university and with their campus partners will reinforce their positive strategic vision and grow the interest of alumni and donors. The positive principle that asking positive questions will bring positive change. The DIVR must ask other campus partners if they have positive stories of diversity and inclusion within their own colleges and divisions. Asking such positive questions will encourage collaboration and shared solutions towards some of the funding and location challenges faced by the DIVR.

Wholeness, enactment, and free choice requires the DIVR to focus on the big picture contribution while acting as if the challenges they face and changes they seek have already happened. The DIVR could conduct their student meetings in a central campus location, they could focus on obtaining more TRiO programs to help more students. Free choice allows them to choose the ways in which they contribute. This empowers the DIVR to influence positive change and demonstrate their impact on student lives within the university.

Finally, the narrative and awareness principle stress the importance of storytelling in bringing positive change. This is paramount for the DIVR considering that their “life-giving forces (p. 2)” rely on their success stories (Cockell & McArthur-Blair, 2012). Consistently engaging in storytelling will assist the DIVR in their fund-raising efforts. Recognition of these success and the impact of the DIVR services across the university will bring to them the attention required for collaboration and support in bringing them to the centerstage of campus. The DIVR must continue to celebrate their successes, share their stories, and engage in the AI process to co-construct the emergent designs required to bring about change.

Institutions of higher education can implement appreciative inquiry by being intentional and collaborative in their processes. They can work on organizational change that is built on appreciative inquiry or apply the 5D model for specific outcomes or purposes of a team or develop a daily practice of appreciative inquiry to support themselves and their teams (Cockell & McArthur-Blair, 2012). During the application of appreciative inquiry, the questions that are asked are crucial. Co-creating visions and action plans stem from the questions asked during the definition, discovery, and design processes. By working with diverse perspectives across all levels within an organization, the appreciative inquiry framework can be a transformative force in higher education.

References

About OSU – Oklahoma State University. (n.d.). Retrieved July 3, 2019, from https://go.okstate.edu/about-osu/index.html

Bolman, L. G., & Deal, T. E. (2017). Reframing organizations: Artistry, choice, and leadership (6th ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: Jossey-Bass.

Brown, S. (2016, March 24). Students should feel like ‘equal partners,’ says Missouri’s first chief diversity officer. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://www.chronicle.com/article/Students-Should-Feel-Like/235821

Cockell, J., & McArthur-Blair, J. (2012). Appreciative inquiry in higher education: A transformative force. San Francisco, CA.: Jossey-Bass.

Diversity Academic Support/TRIO. (n.d.). Retrieved July 3, 2019, from https://das.okstate.edu/

Fry, R., & Parker, K. (2018). Early benchmarks show “post-millennials” on track to be most diverse, best-educated generation yet. Pew Research Center.

Kuh, G. D. (2015). Foreword. In Student Engagement in Higher Education: Theoretical Perspectives and Practical Approaches for Diverse Populations (pp. ix–xiii). Routledge.

Manning, K. (2018). Organizational theory in higher education (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Mission. (n.d.). Retrieved July 3, 2019, from Institutional Diversity website: https://diversity.okstate.edu/mission

OK-LSAMP. (n.d.). Retrieved July 3, 2019, from https://ok-lsamp.okstate.edu/

OSU Diversity Highlights. (n.d.). Retrieved July 3, 2019, from Institutional Diversity website: https://diversity.okstate.edu/osu-diversity-highlights

Quaye, S. J., & Harper, S. R. (2015). Student Engagement in Higher Education: Theoretical Perspectives and Practical Approaches for Diverse Populations. Routledge.

Schein, E. H. (1992). Organizational culture and leadership (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA.: Jossey-Bass.