On the Basis of Sex: The Origins of the Title IX Reforms in the 21st Century

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 is a federal law that prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in an educational institution, public or private, receiving federal funding (Kaplin, 2007). In recent months, the Department of Education, under the leadership of Betsy DeVos, has proposed certain policy changes that would undermine the Title IX protections afforded to victims of sexual harassment and assault in these institutions. Those in favor of the proposed changes question the “excesses” of the amendment’s current protections including over-policing college students (Yoffe, 2018) and due process rights (Brown & Mangan, 2018). Understanding the social, political, and philosophical foundations of Title IX and its interpretations over time will inform our understanding of current arguments surrounding these proposed reforms (Moore, 2018). This paper will delve into these historical foundations of Title IX in the late 20th century and discuss their influences on the present-day challenges.

Foundations of Title IX

Creation

Higher education in the United States was traditionally under the governance of the states (Mumper, Gladieux, King, & Corrigan, 2016). Federal entry and involvement in higher education began with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Higher Education Act of 1965 (Mumper et al., 2016). The Civil Rights Act does not allow discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin in the areas of employment and public accommodation (Kaplin, 2007). This law however, does not apply to educational institutions. Title VI, enacted in 1964, prohibits discrimination in federally funded educational institutions on the basis of race, color and national origin, but ignores sex; Title VII applied only to the private sector (McBride & Parry, 2011). Due to the persistent efforts of the National Organization for Women (NOW), President Lyndyn B. Johnson forbid sex discrimination in federal contracts by signing the Executive Order 11375 in 1965 (McBride & Parry, 2011). Bernice Sandler of NOW and Women’s Equity Action League (WEAL), conceived Title IX with Rep. Edith Green (McBride & Parry, 2011). Rep. Patsy Mink authored Title IX draft with Green and it was presented to the congress by Sen. Birch Bayh in 1971. President Nixon enacted Title IX on 23 June 1972, prohibiting the discrimination on the basis of sex in all federally funded education programs under the oversight of the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) (McBride & Parry, 2011).

Implementation

Although Title IX became the law in 1972, regulations for complying with the law were not published until 1975 (McBride & Parry, 2011). The Department of Health, Aviation and Welfare (HEW), responsible for creating these regulations, were faced with conflicts regarding the extent of “integration of the sexes”, opposition to federal interference in private schools under the states’ purview (McBride & Parry, 2011, p. 129), and athletic interest groups pushing to keep athletics outside the jurisdiction of Title IX (Walters & McNeely, 2010).

These issues may have hampered the ability to enforce Title IX and slowed down the progress of its effects. Durrant (1992) notes that schools were required to identify areas of noncompliance, and develop strategies and timelines for compliance. Legal arguments were not always about the occurrence of sex discrimination but rather if it fell under Title IX’s purview. The scope of its applicability to institutions not accepting federal funds for certain programs such as athletics contrasted as “institutional approach” or “programmatic approach”. Contradictory court decisions exacerbated this issue, and OCR was not adequately funded. The Secretary of Education found institutions to be “in compliance” if they “voluntarily formed a committee to adopt a plan to correct the violations within a reasonable period of time” (Durrant, 1992, p. 62).

Interpretations

Decisions from the United States Supreme Court on cases in the 1980’s and 90’s held sexual harassment and assault as a form of sex discrimination that could be brought forward through Title IX or other civil rights laws (Kaplin, 2007). In 2011, in response to the National Institute of Justice’s reporting that about 20% of women and 6.1% of men are victims of completed or attempted sexual assault while in college, the OCR, under President Barack Obama released a Dear Colleague Letter (Creeley, 2012). This letter reiterated longstanding requirements of Title IX and served as a reminder to federally funded educational institutions to treat sexual harassment and assault cases as civil rights issues (Office for Civil Rights, 2010). The letter also outlined the applicability of Title IX to LGBT students (Office for Civil Rights, 2010).

The guidelines required colleges to change their definition of sexual harassment to include those unwelcome acts of a sexual nature that “limits or denies” versus “denies” a person equal access to education (Medley, 2018). It suggested using a ‘preponderance of evidence’ standard over higher standards of evidence in sexual harassment cases, discouraged cross-examination of the victim by the accused due to its potential to retraumatize victims and suggested a 60-day time period to complete investigations (Brown & Mangan, 2018).

Current Challenges

The U.S. Department of Education, in 2017, rescinded the Title IX enforcement guidelines provided with the Dear Colleague Letter and released proposed regulations in November 2018 (Brown & Mangan, 2018). These new regulations require a much higher standard of “clear and convincing evidence” and uses a more extreme definition of sexual harassment as “an unwelcome conduct on the basis of sex that is so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive that it denies a person equal access to the recipients education program or activity” (Brown & Mangan, 2018, para. 7). Further, the accused will be guaranteed the right to cross-examine the victim and the educational institutions receiving federal funding are relieved from investigating formal complaints from students if the alleged incident did not occur on campus property or within an educational program (Brown & Mangan, 2018). The overarching motivation for these changes appears to be the supposed lack of due process protections for the accused.

To understand the current arguments and motivations for reforming Title IX, it is critical to explore the various social ideas, political attitudes and philosophies that guided and challenged the underlying rhetoric during its creation. While there are many issues surrounding Title IX, the most common theme underlying these issues involve women’s rights and equality. In the next section, I provide a background of the status of women in the 20th century that will inform the uncertainty surrounding Title IX, 46 years later, in the 21st century.

Contextualizing Title IX

There are multiple viewpoints and arguments surrounding Title IX and its applicability. These perspectives can have a large impact on the ways in which Title IX policies are enforced at the institutional level. It is therefore crucial for institutional agents to contextualize Title IX policies in its roots to begin to understand some of these impacts and comprehend the arguments surrounding Title IX.

Historical context

In the mid 18th century, a religious revival known as the Great Awakening spread evangelical theology across the colonies (Lunardini, 1996). Women were the spiritual leaders of their families who volunteered to eradicate societal ills by applying the tenets of their religion (Lunardini, 1996). By the early 19th century, women focused on the injustices and immorality of slavery, and sought its abolition. Upon facing discrimination and not being allowed membership into the established Anti-Slavery Society by male abolitionist leaders, women like Lucrietta Mott, Elizabeth Stanton, and Susan Anthony, in addition to fighting for the abolition of slavery, fought for women’s rights to education, economic opportunity, voting rights, and access to various professions limited to men. Realizing that demands for women’s rights may prevent the passing of anti-slavery laws, the women’s rights movement suspended their activities until African American slaves had been freed (Lunardini, 1996).

By the 19th century, there was an increase in immigrant women who also participated in the labor force and women’s rights movement resurfaced with the Equal Rights Association in 1866, the first national suffrage organization (Lunardini, 1996). The early 20th century saw the birth of the Equal Rights Amendment during WWII when more women were engaged in professional work. By 1963, the Equal Pay Act, the first federal legislation prohibiting sex discrimination had passed (Lunardini, 1996). During the 19th century, higher education dramatically changed by providing access to women, African Americans, and Roman Catholic immigrants (Thelin, 2004). In 1965, federal government entered the higher education arena, primarily under the governance of the states, with the introduction of the Higher Education Act with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Mumper et al., 2016).

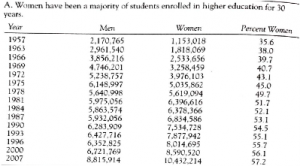

During this time, women were not allowed to engage in physical activity as it was thought to be detrimental for them (Lunardini, 1996). Such constraints against women in sports continued even after Title IX was passed. The impact of Title IX can be seen in the 162.37% increase of women enrolled in higher education compared to the 68.28% increase in men enrolled from 1957 to 2007 as calculated from data presented in Figure 1 (McBride & Parry, 2011, p. 130). Growth in these programs, similar to women’s enrollment, continued to increase over the next 30 years (McBride & Parry, 2011). In 1970, only 7.5% of women in higher education participated in athletics; by 1978 it was 32%, a 570% increase compared to the 13% increase for men in collegiate athletics (Lunardini, 1996). In the 1980’s sexual harassment issues came to the fore and federal legislation required universities to implement written policies and procedures to improve campus culture (Kopecky, 1990)

Figure 1. Enrollment in higher education during the Title IX years (Bledsoe, 1972)

Social Context

In 1922, Alice Paul, an American suffragist, along with other women’s rights activists, drafted the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) which prohibits discrimination against all American citizens regardless of sex. This amendment sparked a national conversation on women’s rights and the meaning of equality as the states were considering the ratification of the bill (Lunardini, 1996). NOW, the Women’s Political caucus, and the Women’s Legal Defense Fund mention employment, property, and credit rights and domestic relations including child care as main concerns in an article in the Commercial Appeal newspaper (Fogg, 1972).

“Equality may be in the process of becoming at least as important to Americans as liberty”, writes sociologist Herbert Gans in an article where he discusses social inequities (“Saturday Review of Society,” 1972). While women were actively participating in fighting for equality, there were others opposed to such rights and created groups such as the “Stop ERA” to spread the message of the devastating effects, in their view, such equality would bring to women everywhere. Archival materials show some first person accounts of concerns of women opposed to equal rights. Mrs. Patterson believed equal rights “would result in women being eligible for drafting into the armed services and in divorcees being unable to collect alimony” (“Women Fight ‘Rights’ Bill,” 1972). Legislators echoed her concerns and added that such rights “force women to lift heavy loads on the job and raise critical questions in areas of child welfare and parental responsibilities” (“House Vote Beats Back Atkins Push,” 1972).

Political Context

The late 19th century was a period of economic and social change in the United States. Activism surrounding women’s rights issues could be seen as early as the Suffrage Movement led by the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), and American Association of University Women (AAUW). These groups, along with the National Organization for Women (NOW) founded in 1966, worked on engaging their communities, developing women to run for office, and working with legislatures to pass legislation to stop discrimination. For example, when women did not succeed as they had hoped during the elections, they put together workshops that empowered and strengthened their chances for the next elections. Some of these include the “Women in Politics” workshop in Baton Rouge consisting of talk sessions by women leaders of the time. Some examples include former Louisiana Representative Lillian Walker’s ”What Must You Do to Run for Office?”, Tennessee coordinator for the National Women’s Political Caucus, or Carleen Waller’s “What Can a Women’s Political Caucus Do for You?”. Others include Margaret McIllhenny of New Orleans and attorney Liz Norman’s discussion on what the ERA would mean to a woman and her family (Marvin, 1972).

Gender differences were brought to light, and women’s place in society was a matter of national discussion and policy debates (Marvin, 1972). Post-World War II, after 1960, assumptions of equality and women’s rights rose. Feminists called for legislation surrounding sex discrimination and litigation began during the mid-1970s with a primary focus on the ERA. Policy debates on women’s rights issues, until President Lyndon Johnson were mostly bipartisan. However, by the 1980’s, there was increasing conservatism in the federal courts, and such bipartisanship withered. Women found support only with the democratic party (McBride & Parry, 2011). This can be seen in an excerpt from a letter written by Anita Miller, President of the Institute for Studies in Equality to Representative Hannah Atkins,

“The women’s movement is in a very dangerous place for the growing climate of conservatism is pervasive. We have begun to feel its impact at every turn: the Congressional action refusing funds for abortion for poor women and legal aid for cases of homosexual discrimination, the Supreme Court’s barbaric ruling which will not recognize pregnancy as a legitimate disability in employee insurance claims, and, most disheartently (sic), the rabid opposition to the ERA (Miller, 1977).”

Miller reflects on the ways conservative politics has impacted womens’ reproductive rights through actions by the congress and the supreme court through “barbaric ruling[s]” and “rabid opposition”.

Conservative influence came for instance, from President Reagan whose administration did not make civil rights issues a high priority (Kopecky, 1990). Their motivation to find loopholes in Title IX along with a conservative federal court allowed only a programmatic approach to Title IX’s jurisdiction, effectively permitting for instance, sex discrimination in athletics as long as federal funding does not go to the athletic department. In Grove City V. Bell in 1984, the United States Supreme Court did just that and gutted the Title IX’s institutional reach (Kaplin, 2007). The Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1988, passed by women’s rights advocates in the Congress, overturned this decision and reinstated the institution-wide penalty for sex discrimination (Kaplin, 2007; Lunardini, 1996).

Philosophical Context

Religious beliefs dictated most opposition to women’s rights at the time of Title IX’s passing. Rev. James Hollingsworth, an outspoken opponent of ERA, told the legislators in senate chambers, “It doesn’t matter how many laws you pass because God’s law establishes the places of women and men. The Bible says that woman is ‘a weaker vessel’ and in the New Testament it says that ‘a woman is to be submissive to man’” (Bledsoe, 1972). Those who feared losing protections or believed that the equal rights would harm women were often misinformed by the messaging of special interest groups. “Sen. Hannah Atkins asked one housewife if she had ever read the Equal Rights Amendment. She never did receive an answer” (Needham, 1972).

While Title IX passed in 1972, women were not necessarily treated as equal in the professions previously held by men. Rep. Helen Arnold, when asked about her experiences with her male colleagues when she served in the House of Representatives in 1976 said, “they (male colleagues) just didn’t think we ought to be there at all” (Finchum, 2008). She recollects a time when she reached the House and greeted a male representative, “Good Morning” and he “grunted” a half-hearted “Good Morning” in response. She added laughing that “They’ve got to learn that there’s a place for women in this House, and they don’t need to just be grumpy old men” and took it in her stride. She also mentioned that women would only be assigned to committees that fit prior rhetoric of women’s roles such as education. Sen. Atkins’ recollection of the times when she would “go out to the Capital early and have breakfast with the good ol’ boys” (Finchum, 2007). She exclaimed that they “didn’t run me away” and “let” her join in and reflected on how she “was on the outside but got inside” the tight circle of male senators. But she alludes to the difference her vote could make as a possible ulterior motive (Finchum, 2007).

Discussion

In the 1990’s, Title IX enforcement was weak and there was a reluctance to hold educational institutions responsible for sexual assault (McBride & Parry, 2011). It appears that such sentiments may have resurfaced with these new reforms where rights of women are seen as less critical in comparison to the cost to the university and Department of Education to enforce Title IX. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), a non-profit organization that defends the civil rights of all the people in America as afforded by the constitution are proponents of due process as well as ensuring students have access to education free of sexual harassment and violence. The ACLU believes that the proposed guidelines would limit the institutions’ responsibility in pursuing sexual harassment complaints under Title IX, would not mandate their response to complaints made to lower level officials, require schools to only investigate extreme complaints of violence per the new definition of harassment, and adopt a standard of proof that favors the accused (Medley, 2018). DeVos’ proposal will invariably harm already marginalized students (Medley, 2018). In her article, Medley points out how sexual harassment and assault, while it can happen to anyone, “disproportionately harms female students, students of color, students with disabilities, and LGBTQ students” (Medley, 2018, para. 9) and argues that the right to due process should not be used to roll back other civil rights.

This proposed reform is consistent with the Trump administration’s multiple attempts to roll back civil rights for these marginalized groups. Parallels can be seen with the Reagan administration’s attempts and success in reducing the scope of Title IX’s reach across the entire institution. Women’s rights to learn in an environment without harassment is seen as less critical than providing rights to the accused. Although the National Sexual Violence Resource Center reports that only 2-10% of sexual assault are falsified, the focus of the administration on the due process rights of those accused over the victims’ rights is reflective of the very discrimination Title IX is meant to eliminate (“Get Statistics,” 2018). The proponents of due process arguments focus on an aggressive narrative geared toward the 2-10% of falsely accused individuals, and diminish the voice and consequently the rights of the 90-98% of victims of sexual harassment and violence. This is similar to the patterns of aggressive counter narratives and misinformation surrounding the ERA in the late 20th century.

Uncertainty around Title IX enforcement now parallels issues surrounding its creation. The “Dear Colleague” letter was released with the intent of providing a safe environment at educational institutions. However, the Obama administration did not have bipartisan Congressional support to make legislative strides in this arena. Avenues such as Dear Colleague Letters, and Presidential executive orders are vulnerable to repeal under a new administration.

What is needed to ensure equal rights going forward is a bipartisan legislation similar to that from the early 20th century under the Johnson administration. Such legislation would consider due process as well as a discrimination-free environment for students involved in Title IX investigations. Legislation such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 took multiple attempts and bipartisan support to become law. These laws are less susceptible to the whims of the administration of the time.

Sen. Bayh, on Title IX’s success said that young women in high schools and Universities were unaware of its protections. “They don’t think they are getting special treatment and they aren’t. They are being treated equally the way they should have been in the first place. Title IX made that possible (The Obama White House, 2012).” Unfortunately, with the current administration’s relentless attack on civil rights, including the Title IX protections, these young women, and marginalized students will become familiar with Title IX as their rights are stripped away, unless they mobilize and fight for equality against all odds as did the many women throughout history.

References

Bledsoe, B. (1972, October 24). Most speakers support amendment.

Brown, S., & Mangan, K. (2018, November 16). What You Need to Know About the Proposed Title IX Regulations. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/article/What-You-Need-to-Know-About/245118

Creeley, W. (2012, January 3). Why the Office for Civil Rights’ April “Dear Colleague Letter” Was 2011’s Biggest FIRE Fight. Retrieved December 9, 2018, from https://www.thefire.org/why-the-office-for-civil-rights-april-dear-colleague-letter-was-2011s-biggest-fire-fight/

Durrant, S. M. (1992). Title IX–Its Power and Its Limitations. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance; Reston, 63(3), 60.

Finchum, T. (2007). Hannah Atkins–Oral History [Oral History] (Vol. Women of the Oklahoma Legislature). Retrieved from https://dc.library.okstate.edu/digital/collection/legislature/id/116/rec/3

Finchum, T. (2008). Helen Arnold–Oral History. Retrieved from https://dc.library.okstate.edu/digital/collection/legislature/id/296/rec/1

Fogg, S. (1972, October 8). Women’s Groups Plan Battle For Property, Credit Rights, p. 2.

Get Statistics. (2018). Retrieved December 11, 2018, from https://www.nsvrc.org/statistics

House Vote Beats Back Atkins Push. (1972, March 29).

Kaplin, W. A. (2007). The law of higher education (4th edition..). San Francisco, CA : Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass ; John Wiley & Sons.

Kopecky, P. W. (1990). A history of equal opportunity at Oklahoma State University. Oklahoma State University.

Lib amendment draws fire. (1972, October 10). The Oklahoma Journal, p. 11.

Lunardini, C. A. (1996). Social Issues in American History Series: Women’s Rights. The ORYX Press.

Marvin, S. (1972, ca). Political woman-power.

McBride, D. E., & Parry, J. A. (2011). Women’s Rights in the USA: Policy Debates and Gender Roles (4th ed.). Taylor & Francis.

Medley, S. (2018, November 16). Betsy DeVos Wants to Roll Back Civil Rights Protections For Students Filing Complaints of Sexual Harassment or Assault. Retrieved December 9, 2018, from https://www.aclu.org/blog/womens-rights/womens-rights-education/betsy-devos-wants-roll-back-civil-rights-protections

Miller, A. M. (1977, July 29). Correspondence.

Mumper, M., Gladieux, L. E., King, J. E., & Corrigan, M. E. (2016). The Federal Government and Higher Education. In American Higher Education in the Twenty-First Century (pp. 212–237). Baltimore, MD: The John Hopkins Press.

Needham, E. (1972, November 25). Equal Rights for Women–The Truth. The Oklahoma Observer.

Office for Civil Rights. (2010, October 26). Dear Colleague Letter on Harassment and Bullying. Retrieved from https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/letters/colleague-201010.pdf

Office for Civil Rights. (2016, May 13). Dear Colleague Letter on Transgender Students. Retrieved from https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/letters/colleague-201605-title-ix-transgender.pdf

Saturday Review of Society. (1972, May 6). Saturday Review.

The Obama White House. (2012). Title IX at 40 – YouTube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Jqj40dybSQ&t=7s

Thelin, J. R. (2004). A history of American higher education. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Walters, J., & McNeely, C. L. (2010). Recasting Title IX: Addressing Gender Equity in the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Professoriate. Review of Policy Research, 27(3), 317–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-1338.2010.00444.x

Women Fight “Rights” Bill. (1972, March 28). Women.

Yoffe, E. (2018, August 1). Reining In the Excesses of Title IX. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2018/09/title-ix-reforms-are-overdue/569215/