Assessing the Campus Climate Survey Surrounding Sexual Violence at Oklahoma State University

Oklahoma State University (OSU) is a public land-grant institution in Stillwater, Oklahoma serving more than 35,000 students across its five-campus systems. The university, receiving federal funding, must comply with Title IX regulations including “monitoring outcomes, identifying and addressing any patterns, and assessing effects on the campus climate (Dear Colleague Letter on Title IX Coordinators, 2015, p. 3). The Title IX Coordinator and their officers, housed under the Office of Equal Opportunity, are interested in conducting a campus climate assessment surrounding sexual violence. Aleigha Mariott, the Deputy Title IX Coordinator and the Director of Student Conduct, is the client for this campus climate assessment and will also serve as the liaison between the evaluator and the Title IX office. She can be reached via phone (405-744-5470) or through email (aleigha.mariott@okstate.edu) or in 328 Student Union. The results from the assessment will inform program improvements and implementations and actions taken in the future that are consistent with student needs.

Need for Campus Climate Assessment

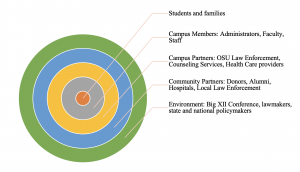

The institution conducted its latest campus climate survey regarding sexual violence in 2017. Since then, OSU has evolved as a campus and seen a shift in the culture within Student Affairs and the Title IX office (A. Mariott, personal communication, September 3, 2019). The current Title IX Coordinator is interested in conducting a campus climate survey to assess current perceptions of students relating to safety and sexual violence to provide improved processes and increased safety on campus to all students at OSU. The stakeholders in the assessment of campus climate at OSU includes all members of the campus community connected to the institution and affected by its climate. Stakeholders in the campus climate surrounding sexual violence at OSU are visualized next.

Purpose for Campus Climate Assessment

The primary purpose of the campus climate assessment is to understand the culture on campus regarding sexual violence and to change processes, procedures, efforts for prevention, and the availability of resources (A. Mariott, personal communication, September 3, 2019). Additionally, the Title IX officers would like to act on the information obtained through their assessment of campus climate. The institution should therefore develop the new survey instrument in ways that are more specific to sexual violence beyond binary responses, as used in previous surveys, to obtain data that leads to actionable information (A. Mariott, personal communication, September 3, 2019). Obtaining actionable information will allow the Title IX office to better serve students, faculty, and staff in creating positive changes across the institution creating a safe climate, free from harassment and discrimination.

Learning Goals and Outcomes

The primary learning goal for this climate assessment is for the institution to articulate student perceptions of sexual violence and consequently, safety on campus. The primary learning outcomes for this assessment will be to appraise and adapt current policies and support systems to accommodate student needs concerning sexual violence at OSU. Additionally, the institution will be able to develop a culture of assessment by conducting this climate survey periodically.

Current survey instruments that are widely utilized by institutions are comprehensive but time-consuming for the participant taking the survey (Wood, Sulley, Kammer-Kerwick, Follingstad, & Busch-Armendariz, 2017). Additionally, data collected is overwhelmingly binary in response styles and do not inform the institutions on decision-making and action plans. For the purpose of this assessment, the evaluator created a curated questionnaire, composed of 20 questions to address these limitations. The survey questions are adapted from the Association of American Universities (AAU) Climate Survey on Sexual Assault and Sexual Misconduct, the Administrator-Researcher Campus Climate Collaborative Survey (ARC3), the Higher Education Data Sharing (HEDS) Consortium Sexual Assault Campus Climate Survey, and resources available through the 1 is 2 many initiative (“1is2many-Oklahoma State University,” n.d.; “AAU Announces 2019 Survey on Sexual Assault and Misconduct | AAU,” n.d.; “ARC3 Campus Climate Survey,” n.d.; “HEDS Sexual Assault Campus Survey,” n.d.)

Assessment Methodology

This assessment, informed by a constructivist perspective, utilized a basic qualitative methodology focused on “how individual’s (sic) experience, conceptualize, perceive, and/or understand (make meaning of)” the survey (Biddix, 2018, p. 55). This basic qualitative design used cognitive interviews conducted face-to-face to assess the validity of the curated survey instrument. It is critical to ensure that the survey instrument is of high quality and demonstrates validity before utilizing the collected data to draw conclusions. To this end, each item in the curated survey instrument requires an in-depth analysis from the perspective of the students taking the survey.

Cognitive Interview Design

The cognitive interview is a method that allows the respondents to “think-aloud” and share their thought processes as they read and answer questions on the survey (Desimone & Le Floch, 2004). This provides the interviewer insight into the respondents’ meaning-making and allows the interviewer to draw emerging themes throughout the process of taking the survey (Tschepikow, 2012). It also eliminates the possibility of respondents responding in ways they think is desired by the interviewer, and ensures that the questions on the survey instrument match the intent of the survey (Desimone & Le Floch, 2004). This method can provide a framework to develop further surveys. The cognitive interview has four stages—“(a) comprehend an item; (b) retrieve relevant information; (c) make a judgment based upon the recall of knowledge; and (d) map the answer onto the reporting system” (Desimone & Le Floch, 2004, p. 6). The interviewer, through this process, can identify the specific stage at which the respondent faces a difficulty in the ways in which they understand and process the survey question before choosing an answer. The feedback from such interviews can help the evaluator operationalize concepts and terms while choosing the ideal language for the target population (A. Manning-Ouellette, personal communication, October 14, 2019). The Oklahoma State University Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved this project on October 21, 2019 before the start of any procedures related to the cognitive interview protocol. A copy of this approval is in the appendix A. A copy of the client’s approval of this project is in appendix B.

Sample selection

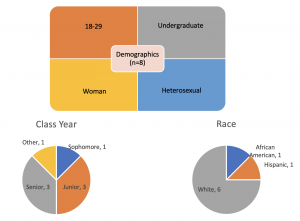

The sample for this assessment (n=8) was selected based on convenience sampling and was composed of student workers at Oklahoma State University working within the offices located at the Student Union.

Data Collection

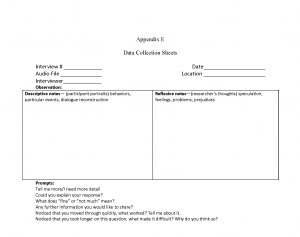

The interviewers conducted the cognitive interview at two points in time and recorded the audio at the interview for triangulation of data. All the cognitive interviews began after obtaining informed consent. The interview protocols, informed consent, and data collection sheets utilized in these interviews are in appendices C, D, and E respectively. During the interview, the interviewers did not answer specific questions asked by the participants, but rather guided them to work through the questions on their own as if they were taking the survey online. In this way, the interviewers could understand how the participants were navigating the survey instrument without influencing the participants’ process and interpretations. Additionally, the interviewers made notes on observations of participants’ body language and facial expressions that may provide information regarding their meaning-making.

The first interview included administering the survey to four participants. Appendix F presents the survey instrument utilized for this round of cognitive interviews. The interviewers—the evaluator and the Deputy Title IX Coordinator, collected and analyzed the data as detailed in the next section. They modified questions on the survey based on emergent themes from the cognitive interviews. These emergent themes and subsequent analyses informed the revisions for the survey instrument. The interviewers administered this revised survey instrument (see Appendix G) as part of a second cognitive interview to four other participants who had not previously participated in this cognitive interview.

Data Analysis

The interviewers analyzed the qualitative data obtained during the cognitive interviews through a systematic approach adapted from the research on student survey participation by William Tschepikow (2012) and the study focusing on cognitive interview usage in education research by Laura Desimone and Kerstin Le Floch (2004). The first stage of analyzing the first set of interviews began with open coding. Through this process, the interviewers reviewed the notes from the interview and coded sections that were insightful and relevant to the research questions. The interviewers identified themes through axial coding by grouping codes together into broader themes and comparing these broader themes to identify overarching themes that address the research questions. These themes informed the interviewers’ decision-making in the ways in which they revised the survey. The interviewers utilized the revised survey for the second set of interviews. The interviewers analyzed the data from this second administration to ensure that the revision addressed the problems highlighted by the first set of interviews, and identified any new problems that may have arisen as suggested by Desimone & Le Floch (2004).

Following the recommendations of Tschepikow (2012), to increase the trustworthiness of these techniques, the interviewers first established inter-rater agreement of analysis and checked with the participants to confirm if the analyses and interpretations were credible and consistent with their processes. Second, the evaluator maintained an audit trail tracking details of every step of the data analysis and the ways in which the interviewers made decisions regarding emergent themes throughout the cognitive interviews. Third, the evaluator increased dependability of the project with the inclusion of peer evaluation by consulting with a research faculty member throughout the course of this project. Additionally, the evaluator also obtained a meta-evaluation of the survey instruments through consultations with other faculty members as recommended by Yarborough (2011). Finally, the evaluator shared the detailed descriptions of the cognitive interview process to increase transferability of the study. This is crucial as these are largely used in the fields of sociology and psychology but not in education (Desimone & Le Floch, 2004).

Evaluation and Assessment Questions

The intent of this assessment is to identify current campus climate and student perceptions of procedures and their experiences with the Title IX office. The primary focus areas for this assessment centers on current student perceptions of sexual violence and safety at Oklahoma State University and prevention measures such as bystander intervention and awareness of resources on campus. The primary assessment questions are:

- What themes emerged as triggers for emotional or physical responses in respondents?

- Did the revisions made to the survey address these themes effectively?

- What (if any) new themes emerged from the revised survey?

Timeline

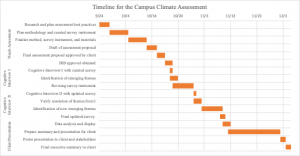

The Gantt chart serves to display the timeline for the project assessing the survey instrument development for the campus climate surrounding sexual violence at OSU.

Assessment Results

Three themes emerged from the data analysis of the first round of cognitive interviews. First, participants identified feeling safe after taking the survey as a result of reading about the various resources available to them. Second, participants highlighted formatting concerns that may have caused them to skip or skim over longer questions, headings, subheadings, definitions, and overviews of the section. The formatting in some cases appeared to confuse them, or hinder their seamless progress through the survey. Finally, the participants’ reactions exposed the ambiguity in certain references regarding location and subject within the survey. The researcher addressed these three concerns and updated the survey instrument as seen in Appendix B. Further analysis revealed that the researcher addressed most of the concerns in the survey resulting from the format and ambiguity as identified in the first version of the survey. However, the reformatting resulted in all participants struggling with the questions Part B: Perceptions of Sexual Violence and Safety, specifically questions B3, B4, and B5. Remarkably, regarding the reading behavior, the participants continued to skip or skim through specific questions, headings, subheadings, definitions, and overviews of the section. These themes are discussed in detail next and a review of the cognitive interview process is depicted through the following schematic.

Themes from the First Round

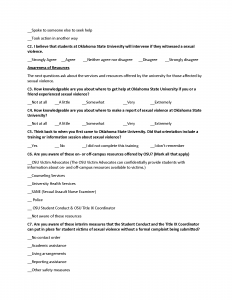

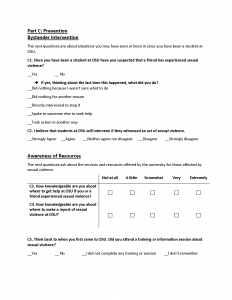

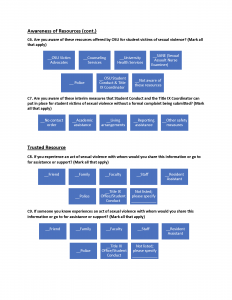

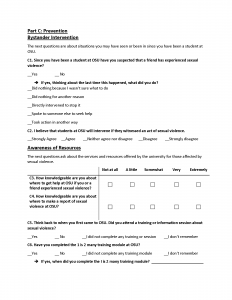

Safety. Participants identified a feeling of safety after completing the survey and attributed it to their knowledge of resources available to them as identified by question C6 and C7 under Part C: Prevention, Awareness of Resources.

Format. First, the overflow of answer choices for a question into the next page, as in A6, C1, and C7, confused the four participants who did not realize there were more choices to these questions, or saw the choices on the following page and paused to find the question. Second, participants tended to consistently skim through, or skip altogether, definitions of sexual violence and preview statements within each section of the survey before the questions. Additionally, participants went through the survey quickly, almost attempting to read as little as possible to complete the survey. This behavior resulted in skimming through long questions, attempting to answer them without fully comprehending the question, and reading the question again slower.

Ambiguity. References to location, such as “Oklahoma State University-Stillwater campus” or “on-campus and off-campus” or “campus official” were ambiguous to the participants. The participants read the institution as “OSU” even when written out in its full form in the survey. Since the interviews were conducted at the Stillwater location, the specific identification of the Stillwater campus only confused these participants. References to “on- and off-campus” in questions B2 and C6 also created confusion as participants tried to understand if residence halls and apartments right by campus constituted on- or off-campus.

References to subject, such as “you or someone you know” as in question C8 were also ambiguous. Participants highlighted the ways in which their actions would differ based on whether the act of sexual violence happened to them versus their friends.

Themes from the Second Round

To effectively address these main themes and concerns from the survey instrument used in the first round, the researcher reformatted the survey. This reformatting included the removal of overflow in answer choices, grouping Likert-scale questions into matrices, illustrating the definition for sexual violence with a schematic representation, adding color to reduce the perceived monotony of long questions, and limiting sections to a page so that each page of the survey addressed specific topics (see Appendix B). The emerging themes from the second round of cognitive interviews utilizing the reformatted and revised survey is explored next.

Part B Matrix Format. The participants from this round of interviews appeared to move through the survey with more ease than their counterparts did in the first round. This was likely a result of the redesign of the survey addressing the overflow issues in answer choices. However, the grouping of Likert-scale questions into matrices presented a new issue in questions B3, B4, and B5. The interviewers identified two main issues for this theme. First, the restructuring caused the long questions to cluster together on one side, making them appear longer. Secondly, these three questions begin with the phrase, “If someone were to report an act of sexual violence to an official at OSU, how likely is it that…”. Combined with the appearance of length due to the cluster, this repetition caused significant confusion to the participants as they attempted to understand the specific change from the previous question(s).

Reading Behavior. Participants continued to skim or skip through headings, subheadings, and overviews of the section. While the participants identified that the schematic for the definition of sexual violence was helpful, they were hesitant to read them aloud during the cognitive interviews. This, however, may be a result of the cognitive interview process itself as participants asked the researchers if they were expected to read the words in the illustration aloud as well when asked about it upon completion of the survey.

Implications to Final Instrument

Based on these findings, the researcher updated the final survey instrument to reduce the appearance of a cluster of questions in B3, B4, and B5, by pulling the common phrase into an overarching question presented before the matrix (see Appendix H). In addition, to be more culture and ability aware, the researchers included “Hispanic” to A4, adjusted the color of the text boxes to more transparent colors, and removed the lines for check marks. The researchers also included choices such as “None” to C6 and C7, “Not Aware”, and “No One” to C8 and C9 based on participants’ comments and recommendations. The evaluator made changes to the final survey instrument based on the thorough feedback obtained through the internal metaevaluation of the assessment project and instruments. These updates are consistent with the program evaluation accuracy and accountability standards (Yarbrough et al., 2011) and CAS standards described next.

Student Affairs Standards of Best Practice

AEA Standards

The Joint Committee on Standards for Educational Evaluation developed a set of standards for the evaluation of educational programs and outlined them in the Program Evaluation Standards by Yarbrough et al. (2011). This assessment project, informed by these standards also focused on the accountability standard through metaevaluations. Internal and external metaevaluations together allow for strong collaborative approaches to systematic program evaluations (Yarbrough et al., 2011). For the purposes of this campus climate survey instrument, the internal evaluator consulted David Mariott, PhD, an external faculty member affiliated with the College of Education at OSU to provide an external metaevaluation. This included applying standards of accountability to the entire design of the cognitive interviews, the procedures used for data collection and analyses, and the survey instruments to ensure that accountability standards are met.

Metaevaluation. Based on this metaevaluation, the evaluator made three main changes to the final instrument. First, questions in Part A: Background were adjusted to allow respondents to write in their age instead of choosing from three options. This was based on the notion that students at OSU are predominantly between the ages of 18-29 and knowing the breakdown of ages within this interval would provide more information for data analyses. This notion was also supported in this evaluation as the eight respondents in these interviews marked the 18-29 option. Another change to this section involved including question A7 requesting the respondent’s living arrangements. Information pertaining to students’ living arrangements could have an impact on understanding their perceptions of safety and campus climate surrounding sexual violence.

Secondly, to demonstrate OSU’s efforts surrounding the prevention of sexual violence, the evaluator included C6 under Part C: Prevention—Awareness of Resources focused on OSU’s mandatory 1 is 2 many sexual violence training module as this may influence respondents’ responses. Knowledge of whether students have completed this training, or recall information covered in such a training has implications to their sense of safety and perceptions of campus sexual violence climate and can affect their responses to the survey questions. Finally, the evaluator added an open-ended question to the survey asking respondents if there are any issues or topics that they believe should have been included in the survey. While this was asked of the respondents during the cognitive interview, by including it as a part of the survey instrument, it is hoped that additional respondents taking the survey at a larger scale will provide actionable information to the client as they explore improvements to their processes in an effort to better support their student community.

CAS Standards

“The Council for Advancement of Standards in Higher Education (CAS) promotes standards to enhance opportunities for student learning and development from higher education programs and services (Wells, 2015, para. 2)”. This evaluation of the created survey instrument through the process of cognitive interviews aligns with the CAS standards and Student Affairs best practices through its learning outcomes in the following student outcome domains:

- Knowledge Acquisition, Construction, Integration, and Application

- Cognitive complexity

- Humanitarianism and Civic Engagement

- Practice Competence

Discussion

The primary findings from this assessment project includes the importance of formatting, length, and language for the intended target student population for campus climate surveys surrounding sexual violence. The reading behaviors across all the respondents interviewed for this assessment suggests that these respondents prefer simple and straightforward questions, are unlikely to read long questions thoroughly, and will skip verbose sections in surveys. Institutional phrases and language surrounding official terminology was generally more ambiguous. It may be advantageous to incorporate terminology and language used by students within the target population than institutional language. The use of cognitive interviews will allow for such clarity and improve future instruments as students can provide feedback on ways to rephrase questions in formats that are meaningful to them.

Established Versus Created Surveys

It is common for higher education administrators to consider investing in large-scale campus climate survey instruments that have demonstrated validity such as those provided by AAU, ARC3, and HEDS. Through this cognitive interview process however, some of the questions that confused respondents, and was flagged by the metaevaluator as problematic were curated verbatim from these valid and established survey instruments. For instance, C1 under Part C: Prevention—Bystander Intervention, C1 asks the respondents what they would do if they suspected that a friend has experienced sexual violence. Three of the respondents and the metaevaluator pointed to the ambiguity in the timing of intervention. They could not identify if the question referred to their actions after the fact or while the act was taking place. In this situation, splitting the question into two options or phrasing them differently would have been more beneficial for the goals of the survey. This curious finding implies that institutions may be better served by using large-scale surveys as a starting point for their campus climate assessment but to improve and develop their own unique tool applicable for their campus needs using other procedures such as cognitive interviews. This would allow for actionable outcomes and increased validity while the length of the survey could be tailored to the institutional response rates and learning goals.

Limitations

The chief limitation of this assessment project is the limited time and resources available for the evaluation. As part of the course requirements for Assessment Techniques in Student Affairs and Higher Education offered over a 16-week period, this evaluation consisted of a small sample size, convenience sampling, and ambiguity regarding campus location.

Sample. The cognitive interviews included a sample of eight respondents. Additional respondents and more detailed interviews with developed instruments could have provided more insight into the ways in which students make meaning out of survey items. This would have likely allowed for stronger themes and improved instruments.

Sampling Method. The short timeline also limited the evaluator’s ability to sample and recruit respondents for the cognitive interview. Convenience sampling resulted in a demographic of student workers in a specific location on campus. However, utilizing sampling methods such as homogenous (specific characteristics) or criterion (specific criteria) sampling would allow for participants from different majors such as liberal arts versus STEM areas, or those living in fraternities and sororities, residential life on-campus, or other off-campus locations. This would allow for a more representative sample for OSU and pertinent variables for study in the perception of safety surrounding sexual violence at OSU.

Reducing Ambiguity. Another limitation as pointed out through the external metaevaluator, is the ambiguity surrounding the interpretations of location (on- and off-campus). This ambiguity can be seen in the respondents’ perceptions of where the acts of sexual violence occur, and in where the Title IX Office and by extension, OSU can address it. The final instrument, would have benefitted from more focused questions surrounding specific locations such as on-campus residence hall, fraternity or sorority, or off-campus locations in ways that eliminated or at the least, considerably reduced this ambiguity.

Recommendations

The Title IX Deputy Coordinator, the client for this assessment project required a survey instrument to assess the campus climate surrounding sexual violence at OSU. The primary outcome from an ideal survey would include information pertaining to student perceptions that would prompt action on the part of the institution. This need is consistent with a culture of assessment that can be viewed as a spiral that does not close but instead is a continuous process in which student learning increases as a result of the ways in which we measure such learning and make meaningful changes (Wehlburg, 2007). The final instrument as included in appendix H is informed by student learning and outcomes using cognitive interviews. The evaluator recommends that this instrument be used a foundation with more intentional homogenous and criterion sampling for further cognitive interviews to develop a campus climate survey surrounding sexual violence that can be administered by the Division of Student Affairs across OSU. While the survey results can inform the Title IX Office of student perceptions and needs, the process of assessing the instrument itself using cognitive interviews would allow for this assessment spiral to inform and improve student services and safety at the university.

References

1is2many-Oklahoma State University. (n.d.). Retrieved December 1, 2019, from https://1is2many.okstate.edu/index.html

AAU Announces 2019 Survey on Sexual Assault and Misconduct | AAU. (n.d.). Retrieved October 9, 2019, from https://www.aau.edu/newsroom/press-releases/aau-announces-2019-survey-sexual-assault-and-misconduct

ARC3 Campus Climate Survey. (n.d.). Retrieved October 9, 2019, from Campus Climate website: https://campusclimate.gsu.edu/arc3-campus-climate-survey/

Biddix, P. J. (2018). Research methods and applications for student affairs. San Francisco, CA.: Jossey-Bass ; John Wiley & Sons.

Dear Colleague Letter on Title IX Coordinators. (2015). 8.

Desimone, L. M., & Le Floch, K. C. (2004). Are we asking the right questions? Using cognitive interviews to improve surveys in education research. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 26(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737026001001

HEDS Sexual Assault Campus Survey. (n.d.). Retrieved October 9, 2019, from HEDS Consortium website: https://www.hedsconsortium.org/heds-sexual-assault-campus-survey/

Tschepikow, W. K. (2012). Why don’t our students respond? Understanding declining participation in survey research among college students. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 49(4), 447–462. https://doi.org/10.1515/jsarp-2012-6333

Wehlburg, C. M. (2007). Closing the Feedback Loop Is Not Enough: The Assessment Spiral. Assessment Update, 19(2), 1–15.

Wells, J. B. (2015). CAS learning and development outcomes. In CAS professional standards for higher education. (9th ed.). Washington, D.C.

Wood, L., Sulley, C., Kammer-Kerwick, M., Follingstad, D., & Busch-Armendariz, N. (2017). Climate surveys: An inventory of understanding sexual assault and other crimes of interpersonal violence at institutions of higher education. Violence Against Women, 23(10), 1249–1267. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801216657897

Yarbrough, D. B., Shulha, L. M., Hopson, R. K., & Caruthers, F. A. (2011). The Program evaluation standards: A guide for evaluators and evaluation users. SAGE.