7.4 Diversity and the Organization

Learning Objectives

- Identify demographic changes that are producing an increasingly diverse labor force and the opportunities (improved recruiting, creativity, problem-solving, flexibility, marketing) and challenges (prejudice, discrimination, stereotypes, ethnocentrism) of this trend for organizations.

- Recognize that balancing your organizational identification and your personal identity—in other words, balancing work and life—ultimately requires a change in organizational cultures so that flexibility becomes the norm and expectation for employers and employees alike.

In thinking about identity and identification, we can easily slip into the trap of thinking the organization has an identity and that, likewise, the employee has an identity. In other words, each has one unified and integrated identity. This mode of thinking is, in fact, the “default” position in Western culture. We think of a each person as a single unit so that, metaphorically, we project this same quality onto the “super-person” which is the organization. Yet Albert and Whetten’s (1985) original thesis about organizational identity readily allowed that organizations can have multiple identities. Communication scholars, as well as researchers in psychology and other fields, have long recognized that the same is true of individuals. Each one of us constructs our sense of self from a multitude of identities—perhaps our family, ethnicity, gender, age country of origin, region or city, religion, hobbies, clubs, alma maters, political affiliations, profession, employer, and work department. Moreover, identity is an ongoing construction that must be constantly negotiated, renegotiated, and adjusted in light of new experiences as you encounter new people and situations. (And from a postmodern perspective, the “self” is a fiction since each person is a “site” where multiple discourses compete. Thoughts and intentions are shaped and conditioned by those discourses and by the language with which to express them.)

To illustrate how people with different (and multiple) identities must mesh to accomplish work, consider this textbook. Under the auspices of a publisher, the three authors came together to perform the work. We share an interest in organizational communication and yet our identities (and their components) are very different. One author (Wrench) is a white male, a member of Generation X who hails from Texas, earned his doctorate in West Virginia, moved from Ohio to New York, has a special interest in learning processes, and identifies with his roles as department chair, teacher, scholar, author, speaker, and consultant. Another author (Punyanunt-Carter) is a woman of color and member of Generation X who also attended universities in Texas and Ohio, and now teaches at her Texas alma mater where she researches, among other interests, fauther-daughter communication. The third author (Ward) is a Baby Boomer who almost exactly mirrors the average (documented by the Bureau of Labor Statistics) of holding 11.3 jobs through the first three decades of his career. White, middle-aged, male, American, Southerner, proud of his alma maters in Virginia and South Carolina, he self-identifies as an academic, teacher, faculty member of his Texas institution, and specialist in organizational and religious communication. Yet through a dozen job changes his identity has varied: writer/editor, corporate communication director, broadcaster, freelance and, upon entering academe in midlife, graduate student, and college professor. Furthermore, two of the authors favor social-scientific research methods while the third holds to an interpretive epistemology. To write this textbook, then, we found ways of making our diversity an advantage rather than a liability.

Or consider your Organizational Communication class. Your class is analogous to an organization with a governing board (the administration), CEO (your instructor), and members (the students). Probably you have experienced how different classes have different “personalities” or, if you will, organizational identities. Somehow, the climate and culture of one class—even just the atmosphere when you walk in the door—is completely different than another class. That identity is driven by many factors: the university, the subject of the class, the instructor, and the composition of the students. And college professors know that different sections of the same course, even during the same semester, have different identities. Thus, for every class in which you are enrolled—including your Organizational Communication class—you must work through the diverse identities of your teachers, your classmates, and yourself in order to pass the course. You must find a way to work with your instructor, and you must cooperate with other students for class discussions and group projects that are integral to the work of each course.

In a very real sense, your textbook and your Organizational Communication class are microcosms of processes that occur daily in the workplace—as individuals and organizations balance the need for a shared identity with the need to accommodate a diverse identities and collectively leverage the strengths they bring to the table. That is the tension we will explore in this section.

Theory and Reality

The notion of boosting performance by encouraging a diverse workforce takes us a long way from the classical theories of management that we encountered in Chapter 3. The theories of Frederick Taylor envisioned the organization as a homogeneous “machine” whose inputs and outputs could be scientifically managed. Max Weber held that bureaucratic management according to impersonal and but fair rules was preferable to the personalized leadership that characterized nineteenth-century capitalism. And Henri Fayol advocated a military style of management based on unity of direction and command. With all these classical theories, individual identities should be left at the factory gate and a diversity of perspectives and opinions would detract from Taylor’s control, Weber’s impartiality, and Fayol’s unity. Yet as we also saw in Chapter 3, the human relations approach to organizations recognized that workers have felt needs, while human resources theories encouraged management to tap worker creativity by enlisting their participation in organizational decision-making. Systems theory likewise, as we learned in Chapter 4, acknowledges that an organization needs a diversity of resources that is sufficient to handle the complexity of its environment. Intepretive approaches suggest that an organization “is” its diversity since the organization and its culture are constituted by the communicative interactions of its various members. Postmodern and critical approaches celebrate diversity by recovering voices that have been historically marginalized in organizations.

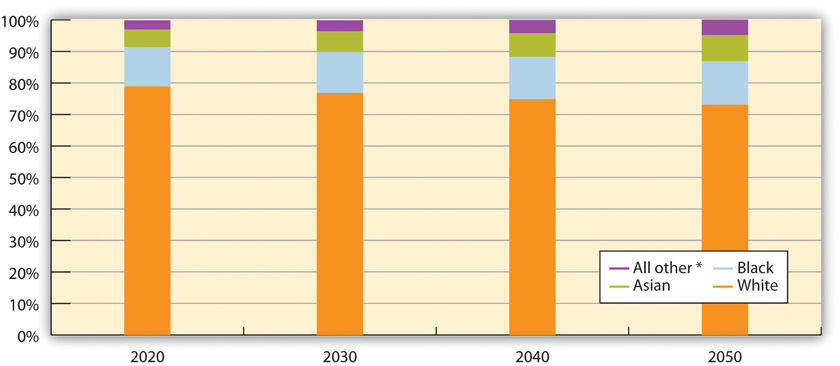

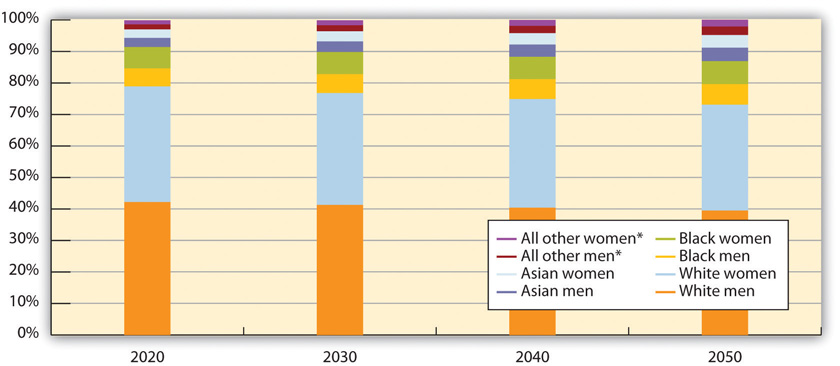

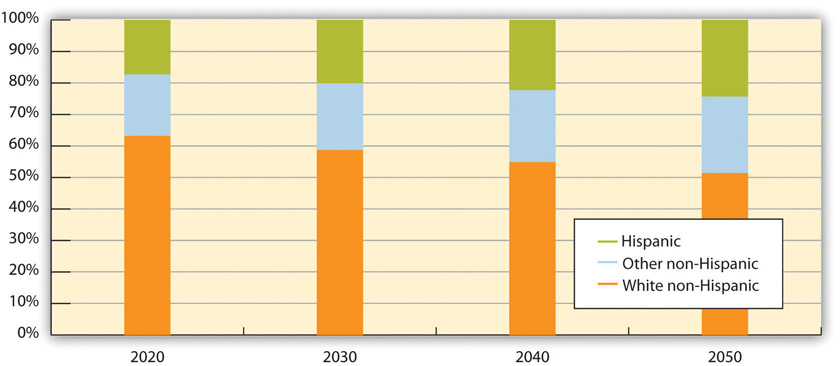

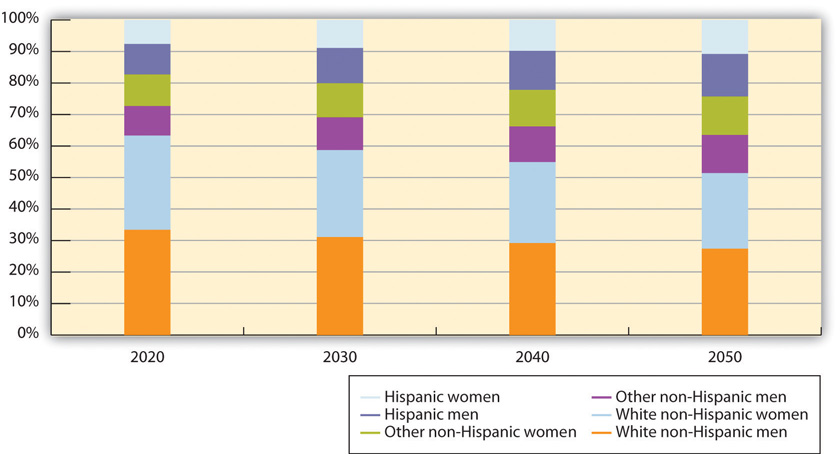

Quite apart from theory, however, is the practical reality of an increasingly diverse workforce in the United States and many other nations. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) tracks numerous demographic traits including age, gender, race and ethnicity, disability, family and marital status, educational attainment, military veteran status, and more. Each trait can be an integral component of a person’s self-identity both in private life and on the job—and in the aggregate, the demographic mix is constantly changing. Organizations must keep abreast of these changes to find and attract the best talent; managers must stay on top of these changes to best help their employees succeed; employees must be aware of these changes to work effectively with coworkers. In 2006, a BLS report projected the composition of the U.S. labor by decade through 2050. The projections, shown in Figure 8.8, Figure 8.9, Figure 8.10, and Figure 8.11 below, suggest steady growth in the numbers of Black, Asian, and Hispanic men and women as percentages of the workforce. But despite the growing numbers of workers in these categories, the agency estimates that overall growth in the U.S. labor force will slow significantly as compared the previous half-century. The Baby Boom generation is aging, while the participation rate of women in the labor force is leveling off after previous decades of rapid growth.

*”All other” includes those classified as of multiple racial origin and the race categories of American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, and other Pacific Islanders.

*”All other” includes those classified as of multiple racial origin and the race categories of American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, and other Pacific Islanders.

Given the trend toward increasingly multicultural workplaces, organizations have solid business reasons to keep pace. Taylor Cox and Stacy Blake (1991) summarized these reasons in six arguments for embracing diversity: (1) Organizations with a reputation for welcoming diverse employees will gain a recruiting edge in a shrinking labor pool, while (2) those that struggle with integrating women and minorities will face increased costs as the labor pool steadily diversifies. Further, organizations with diverse workforces will benefit from the improved (3) creativity, (4) problem-solving and (5) managerial flexibility spurred by multiple viewpoints, even as they (6) gain greater insights for marketing products and services to an increasingly diverse public. Nevertheless, achieving these benefits is not easy because accustomed modes of thinking—whether in an organizational culture, or in the surrounding society—may be transmitted over generations, be deeply ingrained, and be slow to change. A sense of the challenge is suggested in Table 7.6 below, which lists employment practices prohibited by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and examples of violations cited by the agency.

| Protected Categories | “Under the laws enforced by EEOC, it is illegal to discriminate against someone (applicant or employee) because of that person’s race, color, religion, sex (including pregnancy), national origin, age (40 or older),disability or genetic information. It is also illegal to retaliate against a person because he or she complained about discrimination, filed a charge of discrimination, or participated in an employment discrimination investigation or lawsuit.” |

| General Principles | “The laws enforced by EEOC prohibit an employer or other covered entity from using neutral employment policies and practices that have a disproportionately negative effect on applicants or employees of a particular race, color, religion, sex (including pregnancy), or national origin, or on an individual with a disability or class of individuals with disabilities, if the polices or practices at issue are not job-related and necessary to the operation of the business. The laws enforced by EEOC also prohibit an employer from using neutral employment policies and practices that have a disproportionately negative impact on applicants or employees age 40 or older, if the policies or practices at issue are not based on a reasonable factor other than age.” |

Still, the laws inforced by the EEOC can only address discrimination and not prejudice. Prejudice is an unseen attitude; discrimination is the observable behavior driven by prejudice. Prejudicial attitudes need not consist of active malice; a prejudicial attitude can stem from ethnocentrism—the belief that one’s own culture is the best or most natural—and from stereotypes which portray older persons as forgetful, or women as emotional, or the differently abled as helpless, or religious believers as judgmental, or gay men as effeminate, or persons of a given racial or ethnic heritage as lazy, or unscrupulous, or dirty, or timid. Though more than 100,000 individual charge filings were lodged with the EEOC in 2011, enforcement alone cannot end prejudice and its effects. There can be, for example, the silent discrimination that limits the access of women and minorities to informal communication networks and to professional mentors, or turns them into “tokens” so that employers feel no obligation to recruit more. The real path to embracing diverse identities within today’s organizations is in the everyday business of working out relationships of mutual respect and dignity. Brenda Allen (2011), in her study of social identities and communication, concluded with three simple recommendations: be mindful of your own biases, be proactive in setting aside those biases, and fill your communication toolbox with a repertoire of skills for effective and empathetic listening and dialogue.

Balancing Identification and Identity

We opened the chapter by pairing identity and diversity as aspects of organizational life that exist in a tension which must be balanced. This is just as true for you, as an organization member, as it is for the organization. In this concluding section we will cast the identity/diversity balance for individuals as an identification/identity balance. In other words, how do you balance your organizational identification with your personal identity—that is, your need to identify with the organizational sufficiently to be a team member and get satisfaction from you job, with the need to “be your own person” and “have a life”? Concern about work-life balanceTerm often used to describe the issues that arise as individuals attempt to balance the sometimes conflicting demands of their work and their personal lives. is not new; much was said in the postwar years as fathers went back to work and climbed the new corporate ladders, and again a generation later when the rise of two-income households put terms such as latchkey kid and supermom into the popular vocabulary. Today with the rise of the Internet and social media, many are concerned about the subtle ways that work is “colonizing” personal life as employees are increasingly pressured to answer work-related emails at home and be available 24/7 to answer phone calls, texts, and tweets from supervisors, coworkers, clients, and customers.

Since the 1990s some organizations have experimented with alternative work arrangements including flex time (flexible working hours), telecommuting or flex place (working from home a certain number of days per week), and job sharing (allowing a full-time job to be shared by two or more part-time employees). Yet the Families and Work Institute (FWI), in its 2012 National Study of Employers, found that the “culture of flexibility” had stagnated due to the economic pressures of the 2008–09 recession. After surveying more than a thousand U.S. organizations of all sizes and occupations, FWI discovered that on the one hand, since 2005 “employers have increased their provision of options that allow employees to better manage the times and places in which they work” through flex time, flex place, and other policies. But on the other hand, “employers have reduced their provision of options that involve employees spending significant amounts of time away from full-time work” through opportunities to move between full- and part- time status and with career breaks for personal or family responsibilities. Employees thus have more options for managing their daily time but fewer options for managing their lives and careers.

Still, the availability of more flex time is a positive step. But why, then, did a 2008 FWI study find that between two-thirds and three-quarters of employee in various occupations reported “not having enough time” to spend with their spouses, partners, or children? (Matos & Galinsky, 2011, pp.12-13). The same survey revealed that, even when employees have access to schedule flexibility, 70 percent use it no more than once a month and 19 percent never use it. Even to care for a sick child, employed parents took an average of only 3.6 days off per year (Matos & Galinsky, 2011, p. 5). “[H]aving access to flexibility options is one thing, but having a culture that supports their use is another. Employees can have substantial access to flexibility, but when they feel that its use is not condoned, they might as well not have access. . . . [A] culture of flexibility is as, if not more, important than simply having access to flexibility options” (Matos & Galinsky, 2011, p. 14). Since 89 percent or more of employees in all occupations surveyed reported that their supervisors are responsive to requests for time off, then “the obstacles to using flexibility likely reside with coworkers, senior leaders, clients, and with employees’ perceptions of the organizational norms” (Matos & Galinsky, 2011, p. 14).

This returns us, of course, to the issue of balancing identification and identity—how much you identify with your organization, versus how much you construct your identity from other sources and maintain that identity. In modern societies where many people spend the bulk of their waking hours at work—and where many people accept job transfers that uproot them from traditional sources of identity—striking a good balance between work and life is a challenge. In the United States, the “culture of flexibility” that organizations need to accommodate a diverse workforce has run up against the ingrained expectation that employees should, heart and soul, be “company people.” The “right” balance between work and life, between organizational identification and selfidentity, is different for each person. You will need to decide what is right for you. But knowledge is power. In this chapter we have learned about the processes by which an organization forms an identity, by which it attempts to socialize employees into that identity, and by which employees acquire an organizational identification. We have learned about identity regulation, concertive control, and technologies of the body through which modern organizations “produce” employees who discipline themselves according to desired norms. With this knowledge you can look squarely at organizational processes, question assumptions that may be taken for granted as normal and natural, and make informed choices about your own participation.

Key Takeaways

- Black, Asian, and Hispanic men and women will comprise steadily increasing percentages of the U.S. labor force through at least 2050. Yet the total labor force will grow slowly as Baby Boomers retire and the participation rate of women levels off after rising rapidly in previous decades. Organizations that embrace a diverse labor force will, as Cox and Blake summarized, enjoy a recruiting edge in a shrinking labor pool and benefit from the creativity, problem-solving, flexibility, and marketing insights generated by diverse perspectives. But as large number of charges filed annually with the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission suggest, prejudicial attitudes and stereotypes still lead to workplace discrimination. This discrimination may be subtle, perhaps as women and minorities are denied access to informal networks and mentors. Brenda Allen recommends three simple steps: be mindful, be proactive, and fill your communication toolbox with effective listening and dialogue skills.

- Although organizations are increasingly willing to provide some measure of daily schedule flexibility for their employees, they have been less willing in recent years to give significant time off (beyond what the law requires) to employees who desire a career break for parenting or other caregiving responsibilities. Even so, large majorities of employees who do have access to scheduling flexibility seldom or never use it. The reason is not that supervisors are unresponsive. Rather, the cultures of most workplaces assume that strong organizational identification and dedication should be the norm. Awareness of how organizational identity and identification are formed can help you assess the processes occurring around you and make informed choices for balancing work and life.

Exercises

- Throughout the section exercises in this chapter, you have thought about a specific organization to which you have belonged—perhaps a sport teams, a club, a house of worship, a workplace, or the college you attend. Think one more time about this organization. Could it benefit from taking a more proactive stance toward recruiting a diverse membership? If so, make a list of how the organization would gain a recruiting edge over other organizations, and how a greater diversity of perspectives within its membership could improve creativity and problem-solving and help the organization do a better job of getting its message out to a diverse public. Think of specific instances when the organization’s actions could have been more effective if its membership and leadership were more diverse.

- Chances are that you have struggled with balancing your personal life with your work—whether that work was a job, or school, or your involvement in community organizations or clubs. To what extent do you think that your decisions about the amount of time you spend at work, at school, or in other involvements are shaped by your identification with the organization in question?To what extent is it shaped by the norms and expectations of that organization’s culture? Has there ever been a time when you overcommitted yourself? Why? Jot down your thoughts. How could the information in this chapter have helped you make more informed choices?

References:

Albert, S. A, & Whetten, D. A. (1985). Organizational identity. Research in Organizational Behavior, 7, 263–295.

Allen, B. J. (2011). Difference matters: Communicating social identity. Long Grove, IL: Waveland.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2012, July 25). Number of jobs held, labor market activity, and earnings growth among the youngest baby boomers: Results from a longitudinal survey summary. Retrieved from: http://www.bls.gov/news.release/nlsoy.nr0.htm

Cox, T. H., & Blake, S. (1991). Managing cultural diversity: Implications for organizational effectiveness. Academy of Management Executive, 5(3), 45–56.

Matos, K., & Galinsky, E. (2011). Workplace flexibility in the United States: A status report. New York: Families and Work Institute.

Matos, K., & Galinsky, E. (2012). 2012 National Study of Employers. New York: Families and Work Institute.

Toossi, M. (2006, November). A new look at long-term labor force projections to 2050. Monthly Labor Review [electronic version]. Retrieved October 26, 2012, from http://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2006/11/art3full.pdf

U.S. Equal Employment Opportinty Commission (n.d.). Prohibited employment policies/practices. Retrieved October 26, 2012, from http://www.eeoc.gov/laws/practices/index.cfm

U.S. Equal Employment Opportinty Commission (n.d.). EEOC charge receipts by state (includes U.S. territories) and basis for 2011. Retrieved October 26, 2012, from www1.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/state_11.cfm

The unseen attitudes that lead to discrimination.

The observable actions that are prompted by prejudicial attitudes.

The belief that one’s own culture is the most natural and is superior to others.

Generalizations that ascribe certain traits to all members of a social classification; e.g., older persons are forgetful, women are emotional, the differently abled are helpless, religious believers are judgmental, gay men are effeminate, or persons of a given racial or ethnic heritage are lazy, or unscrupulous, or dirty, or timid.