6.2 Approaches to Leadership

Learning Objectives

- Explain the trait approach to leadership.

- Differentiate between Fred Fiedler’s Contingency Theory and Paul Hersey and Kenneth Blanchard’s Situational Leadership Theory as situational approaches to leadership.

- Understand the similarities and differences between Chester Barnard’s Functions of the Executive and Kenneth Benne and Paul Sheats’ Classification of Functional Roles in Groups as functional approaches to leadership.

- Compare and contrast Robert Blake and Jane Mouton’s Managerial Grid and George Graen’s Leader-Member Exchange Theory as relational approaches to leadership.

- Explain James MacGregor Burns’ Transformational Approach to leadership.

As with most major academic undertakings, there is little agreement in what makes a leader. Since the earliest days of the study of business, there have been discussions of leadership. However, leadership is hardly a discussion that was originated with the advent of the academic study of businesses. In fact, the oldest known text in the world, The Precepts of Ptah-hotep, was a treatise written for the Pharaoh Isesi’s son (of the fifth dynasty in Egypt) about being an effective Pharaoh (or leader) (Wrench, 2013). Although it’s relatively easy in hindsight to look at how effective an organizational leader was based on her or his accomplishments, determining whether or not someone will be an effective leader prior to their ascension is a difficult task. To help organizations select the “right” person for the leadership role, numerous scholars have come up with a variety of ways to describe and explain leadership. According to Michael Hackman and Craig Johnson (2009), “Over the past 100 years, five primary approaches for understanding and explaining leadership have evolved: the traits approach, the situational approach, the functional approach, the relational approach, and the transformational approach [emphasis in original]” (p. 72). The rest of this section is going to explore these different approaches to leadership.

Trait Approach

The first major approach to leadership is commonly referred to as the trait approach to leadership because the approach looks for a series of physical, mental, or personality traits that effective leaders possess that neither non-leaders nor ineffective leaders possess. We start with this approach to leadership predominantly because it’s the oldest of the major approaches to leadership and is an approach to leadership that is still very much in existence today. The first major study to synthesize the trait literature was conducted by Ralph Stogdill in 1948. In 1970, Stogdill reanalyzed the literature and found six basic categories of characteristics that were associated with leadership: physical, social background, intelligence and ability, personality, task-related, and social (Bass, 1990). Table 6.2 contains a list of the personality traits from the 1970 study in addition to other researchers who have discovered a variety of other traits associated with leadership.

| Stogdill (1970) |

|

| Mann (1959) |

|

| Kirpatrick & Locke (1991) |

|

| Lussier & Achua (2007) |

|

From Table 6.2 you can start to see that research has found a variety of different traits associated with leadership over the years. Notice, that there is some overlap, but each list is clearly unique. In fact, one of the fundamental problems with the trait approach to leadership is that research has provided a never-ending list of personality traits that are associated with leadership, so no clear or replicable list of traits exists.

Even communication researchers have examined the possible relationship between leadership and various communication traits. In an experimental study conducted by Sean Limon and Betty La France (2005), the researchers set out to see if an individual’s level of three communication traits could predict leadership emergence within a group. The three communication traits of interest within this study were communication apprehension (“fear or anxiety associated with either real or anticipated communication with another person or persons” [McCroskey, 1984, p. 13]), argumentativeness (“generally stable trait which predisposes the individual in communication situations to advocate positions on controversial issues and to attack verbally the positions which other people take on these issues” [Infante & Rancer, 1982, p. 72]) and verbal aggressiveness (“attack one’s self-concept instead of, or in addition to, one’s positions on a topic of communication” [Infante & Wigley, 1986]).

Ultimately, the researchers found that an individual’s level of argumentativeness positively predicted an individual’s likelihood of emerging as a leader while an individual’s communication apprehension negatively predicted an individual’s likelihood of emerging as a leader. Verbal aggression, in this study, was found to have no impact on an individual’s emergence as a leader. In other research, leader verbal aggression was found to negatively impact employee level of satisfaction and organizational commitment while argumentativeness positively related to employee level of satisfaction and organizational commitment (de Vries, Bakker-Pieper, & Oostenveld, 2010). These three communication traits demonstrate that an individual leader’s communication traits can have an impact on both an individual’s emergence as a leader and how followers will perceive that leader.

The original notion that leaders were created through a magic checklist of personality traits has fallen out of favor in the leadership community (Dinh & Lord, 2012).However, more recent developments in leadership theory have been reintegrating the importance of personality traits as important aspects of the process of leadership. In Scott Shane’s book (2010) Born Entrepreneurs, Born Leaders: How Genes Affect Your Work Life, he argues that while genetics may not cause humans to become leaders or entrepreneurs, one’s genetic makeup probably influences the likelihood that someone would become a leader or entrepreneur in the first place. In the same vein, Jessica Dinh and Robert Lord have argued that personality traits should be examined within specific leadership events instead of as fundamental aspects of some concrete phenomenon called “leadership” (Zaccaro, 2007). In essence, Dinh and Lord argue that an individual’s personality traits may impact how they behave within specific leadership situations but that specific personality traits may not be seen across all leaders in all leadership contexts.

Situational Approach

As trait approaches became more passé, new approaches to leadership began emerging that theorized that leadership was contingent on a variety of situational factors (e.g., task to be completed, leader-follower relationships/interactions, follower motivation/commitment, etc.). These new theories of leadership are commonly referred to as the situational approaches. While there are numerous leadership theorists who fall into the situational approach, we’re going to briefly examine two of them here: Fred Fiedler’s Contingency Theory and Paul Hersey and Kenneth Blanchard’s Situational Leadership Theory.

Fred Fiedler’s Contingency Theory of Leader Effectiveness

Fred Fiedler began developing his theory of leadership in the 1950s and 60s and eventually coined it the “Contingency Theory of Leader Effectiveness” (Fiedler, 1967). In his theory, Fiedler believed that leadership was a reflection of both a leader’s personality and behavior, which were constant. Fiedler believed that that leaders do not change their leadership styles, but rather when situations change, leaders must adapt their leadership strategies. Fiedler’s basic theory started with the notion that leaders typically were either task-oriented or relationship-oriented. Task-oriented leaders focused more on the task and accomplishing organizational goals. Relationship-oriented leaders focused on creating positive interactions with followers and establishing positive relationships based on mutual trust, respect, and confidence.

To determine a leader’s preference for tasks or relationships, leaders are asked to think about all of the followers with whom they’ve worked and select the one follower with whom they’ve had the most problems. By thinking about the follower with whom the leader has had the most problems, it’s generally very easy to determine if the leader is more task or relationship-oriented because that follower is generally the opposite. Fiedler, termed this follower the leader’s least preferred coworker (LPC).

Once a leader’s LPC is determined, Fielder’s model asks leaders to examine their situation favorableness, or the degree to which a leader can influence her or his followers within a given situation. To determine situational favorableness, leaders must examine three distinct aspects of their leadership style: leader-member relations, task structure, and position power.

Leader-Follower Relations

The first factor of situation favorableness leaders must attend to involves the nature of their relationship with their followers. Leaders who have positive relationships with their followers will have high levels of mutual trust, respect, and confidence; whereas leaders with negative relationships with their followers will have lower degrees of mutual trust, respect, and confidence. The more positive a leader’s relationships with her or his followers, the more favorable the situation will be for the leader.

Task Structure

Next, leaders must determine if the task at hand is one that is highly structured or one that that is unstructured. Highly structured tasks are ones that tend to be repetitive and unambiguous, so they are more easily understood by followers, which leads to a more favorable situation for the leader. If tasks are unstructured, then the leader will have followers who are less likely to understand the task, which will make for a less favorable leadership situation.

Position Power

Lastly, leaders need to know whether they are in a position of strong or weak power. Leaders who have the ability to exert power over followers (reward and punish followers), will have greater ability to exert the leader’s will on followers, which is more favorable for the leader. Leaders who do not have the ability to exert power over followers are in a much less favorable leadership situation.

Situational Favorableness

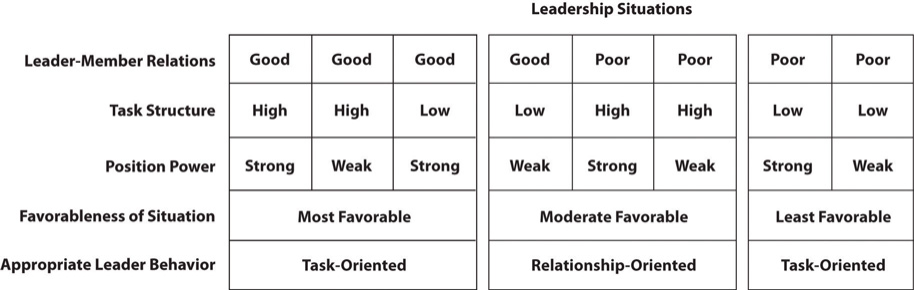

When one combines the three factors (leader-follower relations, task structure, and position power), the basic contingency model proposed by Fiedler emerges. Figure 6.1 illustrates the basic model proposed.

In this model, you can see that the combination of the three factors create a continuum of most favorable to least favorableness for the leader. Notice that there are eight basic levels ranging from the left side of the model, which is more favorable, to the right side of the model, which is least favorable. One area of concern that can impact the usability of this model is ultimately a leader’s LPC. If the situation matches a leader’s LPC, the leader is lucky and he or she doesn’t need to alter anything. However, often the situation leads to an imbalance between the leader’s LPC and the appropriate leader behavior necessitated by a situation. In this case, the leader can either attempt to alter her or his leadership style, which is not likely to lead to a positive outcome, or the leader can attempt to change the situation to match her or his LPC style, which will be more likely to lead to a positive outcome.

Paul Hersey and Kenneth Blanchard’s Situational Leadership Theory

Like Fielder’s Contingency Model, the basic model proposed by Paul Hersey and Kenneth Blanchard (1969) is also divided into task (leader directive behavior) and relational (leader supportive behavior) dimensions. However, Hersey and Blanchard’s theory of leadership starts with the basic notion that not all followers need the same task or relationship-based leadership, so the type of leadership a leader should utilize with a follower depends on the follower’s readiness. Figure 6.2 shows the basic model.

In the basic model seen in Figure 6.2, you have both dimensions of leadership behavior (supportive and directive). Based on these two dimensions, Hersey and Blanchard propose four basic types of leadership leaders can employ with various followers depending on the situational needs of the followers: directing, coaching, supporting, and delegating (Hershey, Blanchard, & Johnson, 2000).

Directing

The first type of leader discussed in Hersey and Blanchard’s (1969) Situational Leadership Theory is the directing leader (originally termed telling). A directing leader is needed by followers who do lack both the skill and the motivation to perform a task. Hersey and Blanchard (1969) recommend against supportive behavior at this point because the supporting behavior may be perceived as a reward by the follower. Instead, these followers need a lot of task-directed communication and oversight.

Coaching

The second type of leader discussed in Hersey and Blanchard’s (1969) Situational Leadership Theory is the coaching leader (originally termed selling). The coaching leader is necessary when followers have a high need for direction and a high need of support. Followers who are unable to perform or lack the confidence to perform the task but are committed to the task and/or organization need a coaching leader. In this case, the leader needs to have more direct control over the follower’s attempt to accomplish the task, but the leader should also provide a lot of encouragement along the way.

Supporting

Next, you have followers who still require low levels of direction from leaders but who need more support from their leaders. Hersey and Blanchard (1969) see these followers as individuals who more often than not have requisite skills but still need their leader for motivation. As such, supporting leaders should set about creating organizational environments that foster these followers’ motivations.

Delegating

Lastly, when a follower is both motivated and skilled, he or she needs a delegating leader. In this case, a leader can easily delegate tasks to this individual with the expectations that the follower will accomplish the tasks. However, leaders should not completely avoid supportive behavior because if a follower feels that he or she is being completely ignored, the relationship between the leader and follower could sour.

Functional Approach

In both the trait and situational approaches to leadership, the primary outcome called “leadership” is a series of characteristics that help create the concept. The functional approach, on the other hand, posits that it’s not a series of leadership characteristics that make a leader, but rather a leader is someone who looks like, acts like, and communicates like a leader. To help us understand the functional approach to leadership, we’ll examine two different sets of researchers commonly associated with this approach: Chester Barnard’s Functions of the Executive and Kenneth Benne and Paul Sheats’ Classification of Functional Roles in Groups.

Chester Barnard’s (1938) The Functions of the Executive

The first major functional theorist was an organizational researcher by the name of Chester Barnard who published a groundbreaking book in 1938 titled The Functions of the Executive. It is from this book’s title that the functional approach to leadership gets its name. In this book, Barnard argues that executives have three basic functions.

Formulating Organizational Purposes and Objectives

The first function a leader should have is the creation (or formulation) of the organization’s basic purpose and its objectives. In essence, leaders should be able to form a clear vision for the organization and then set about creating the tasks necessary to help the organization accomplish that vision.

Securing Essential Services from Other Members

The second function of a leader according to Barnard’s framework was securing essential services from other members. Barnard realized that one of the inherent aspects of leadership was the leader’s ability to get the services he or she needs from followers. For example, it’s not just about hiring people and setting them about their tasks. Instead, it’s about hiring people and then inspiring those followers in an effort to get the best out of them. In an organization where someone has a position of leadership but is not at the top of the hierarchy, leadership also becomes important in an individual’s ability to reach out to other teams or divisions and secure resources and services to help the leader’s team accomplish its goals. Basically, leaders must actively work to help others accomplish the organization’s goals.

Establishing and Maintaining a System of Communication

According to Barnard, the first function of an executive should be to establish and maintain a system of communication. As such, Barnard (1938) came up with seven specific rules to help executives create a system of communication within their organizations:

- The channels of communication should be definite;

- Everyone should know of the channels of communication;

- Everyone should have access to the formal channels of communication;

- Lines of communication should be as short and as direct as possible;

- Competence of persons serving as communication centers should be adequate;

- The line of communication should not be interrupted when the organization is functioning; and

- Every communication should be authenticated.

From this perspective, leaders have a fundamental task in creating and controlling both the formal and informal communication systems within the organization. In fact, Chester Barnard was one of the first researchers to really extol the importance of understanding both the formal and informal communication within an organization.

Kenneth Benne and Paul Sheats’ Classification of Functional Roles in Groups

Kenneth Benne and Paul Sheats did not exactly set out to create a tool for analyzing and understanding the functional aspects of leadership. Instead, their 1948 article titled “Functional Roles of Group Members” was designed to analyze how people interact and behave within small group or team settings. The basic premise of Benne and Sheat’s 1948 article was that different people in different group situations will take on a variety of roles within a group. Some of these roles will be prosocial and help the group accomplish its basic goals, while other roles are clearly antisocial and can negatively impact a group’s ability to accomplish its basic goals. Benne and Sheats categorized the more prosocial roles as belonging to one of two groups: task and group building and maintenance roles. Task roles are those taken on by various group members to ensure that the group’s task is accomplished. Group building and maintenance roles, on the other hand, are those roles people take on that are “designed to alter or maintain the group way of working, to strengthen, regulate and perpetuate the group as a group” (Benne & Sheats, 2007, p. 31). The more anti-social (individual) roles are roles group members take on that are not relevant to neither the group nor the task at hand. Individuals embodying these roles will actually prevent the group from accomplishing its task in a timely and efficient manner. We will go into more detail about the specific nature of these various roles in Chapter 9, for now let’s just look at Table 6.3.

| Prosocial Group Roles | Antisocial Group Roles |

| Task Roles | Individual Roles |

|

|

| Group Building & Maintenance Roles | |

|

So, you may be wondering how these actually relates back to the notion of leadership. To help us understand why these roles are functions of leadership, let’s turn to the explanation provided by Michael Hackman and Craig Johnson (2009):

Roles associated with the successful completion of the task and the development and maintenance of group interaction help facilitate goal achievement and the satisfaction of group needs. These roles serve a leadership function. Roles associated with the satisfaction of individual needs do not contribute to the goals of the group as a whole and are usually not associated with leadership. By engaging in task-related and group-building/maintenance role behaviors (and avoiding individual role behavior), a group member can perform leadership functions and increase the likelihood that he or she will achieve leadership status with the group. (p. 89)

In essence, leaders are people who perform task and relational roles while people who are non-leaders tend to focus on their own desires and needs and not the needs of the group itself. As such, each of the task and building/maintenance roles can be considered functions of effective leadership.

Relational Approach

The next approach to leadership is called the relational approach because it focuses not on traits, characteristics, or functions of leaders and followers, but instead the relational approach focuses on the types of relationships that develop between leaders and followers. To help us understand the relational approach to leadership, let’s examine two different perspectives on this approach: Robert Blake and Jane Mouton’s Managerial Grid and George Graen’s Leader-Member Exchange Theory.

Robert Blake & Jane Mounton’s Managerial Grid

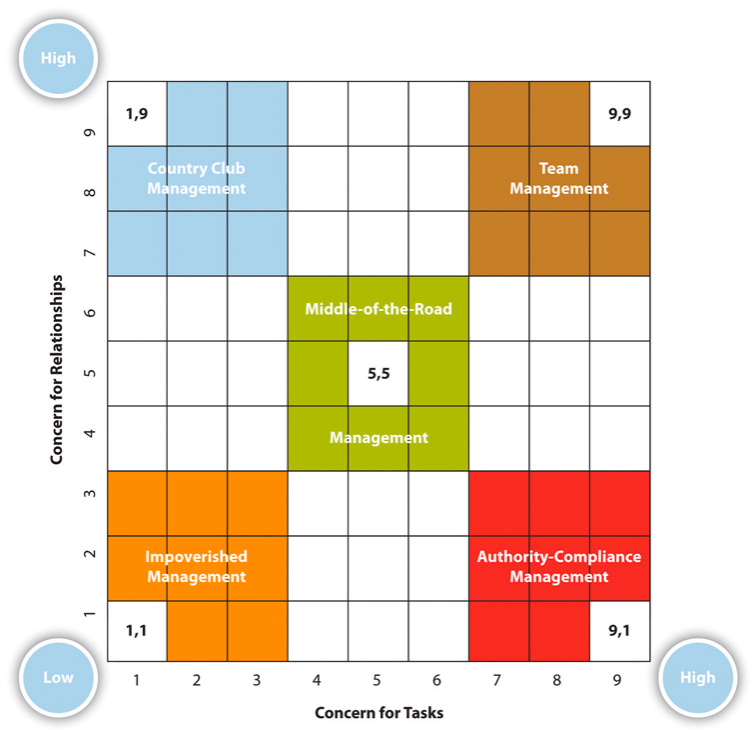

The first major relational approach we are going to discuss is Blake and Mounton’s (1964) Managerial Grid. While the grid is called a “management” grid, the subtitle clearly specifies that it is a tool for effective leadership. In the original grid created in 1965, the two researchers were concerned with whether or not a leader was concerned with her or his followers or with production. In the version we’ve recreated for you in Figure 6.3, we’ve relabeled the two as concern for relationships and concern for tasks to keep consistent with other leadership theories we’ve discussed in this chapter. The basic idea is that on each line of the axis (x-axis refers to task-focused leadership; y-axis refers to relationship-focused leadership) there are nine steps. Where an individual leader’s focus both for relationships and tasks will dictate where he or she falls as a leader on the Managerial Grid. As such, we end up with five basic management styles: impoverished, authority compliance, country club, team, and middle-of-the-road. Let’s look at each of these in turn.

Impoverished Management

The basic approach a leader takes under the impoverished management style is completely hands off. This leader places someone in a job or assigns that person a task and then just expects it to be accomplished without any kind of oversight. In Blake and Mouton’s (2011) words, “the person managing 1,1 has learned to ‘be out of it,’ while remaining in the organization… [this manager’s] imprint is like a shadow on the sand. It passes over the ground, but leaves no permanent mark” (p. 315-316).

Authority-Compliance Management

The second leader is at the 9,1 coordinates in the leadership grid. The authority-compliance management style has a high concern for tasks but a low concern for establishing or fostering relationships with her or his followers. Consider this leader the closest to resemble Fredrick Taylor’s scientific management style of leadership. All of the decision-making is made by the leader and then dictated to her or his followers. Furthermore, this type of leader is very likely to micromanage or closely oversee and criticize followers as they set about accomplishing the tasks given to them.

Country Club Management

The third type of manager is called the country club management style and is the polar opposite of the authority-compliance manager. In this case, the manager is almost completely concerned about establishing or fostering relationships with her or his followers, but the task(s) needing to be accomplished disappears into the background. When assigning tasks to be accomplished, this leader empowers her or his followers and believes that the followers will accomplish the task and do it well without any kind of oversight. This type of leader also adheres to the advice of Thumper from the classic Disney movie Bambi, “If you can’t say anything nice, don’t say anything at all.”

Team Management

The next leadership style is at the high ends of concern for both task and relationships, which is referred to as the team management style. This type of leader realizes that “effective integration of people with production is possible by involving them and their ideas in determining the conditions and strategies of work. Needs of people to think, to apply mental effort in productive work and to establish sound and mature relationships with one another are utilized to accomplish organizational requirements” (Blake & Mouton, 2011, p. 317). Under this type of management, leaders believe that it is their purpose as leaders to foster environments that will encourage creativity, task accomplishment, and employee morale/motivation. This form of management is probably most closely aligned with Douglas McGregor’s Theory Y, which was discussed previously in Chapter 3.

Middle-of-the-Road Management

The final form of management discussed by Blake and Mouton was what has been deemed the middle-of-the-road management style. The reasoning behind this style of management is the assumption that “people are practical, they realize some effort will have to be exerted on the job. Also, by yielding some push for production and considering attitudes and feelings, people accept the situation and more or less ‘satisfied’ [emphasis in original]” (Blake & Mouton, 2011, p. 316). In the day-to-day practicality of this approach, these leaders believe that any kind of extreme is not realistic, so finding some middle balance is ideal. If, and when, an imbalance occurs, these leaders seek out ways to eliminate the imbalance and get back to some state of moderation.

George Graen’s Leader-Member Exchange Theory

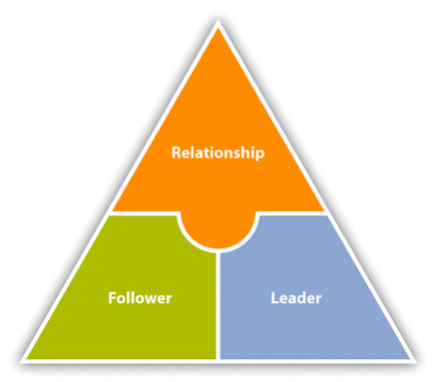

Starting in the mid-1970s, George Graen proposed a different type of theory for understanding leadership. Graen’s (1995) theory of leadership proposed that leadership must be understood as existing in three distinct domains: follower, leader, and relationship (Figure 6.4). The basic idea is that leaders and followers exist within a dyadic relationship, so understanding leadership must examine the nature of that relationship.

When examining the leader-member exchange (LMX) relationship, one must realize that leaders have only limited amounts of social, personal, and organizational resources, so leaders must be selective in how they distribute these resources to their followers. Ideally, every follower would have the same type of exchange relationship with their leader, but for a variety of reasons some followers receive more resources from a leader while others receive less resources from a leader. Ultimately, high-quality LMX relationships are those “characterized by greater input in decisions, mutual support, informal influence, trust, and greater negotiating latitude;” whereas, low-quality LMX relationships “are characterized by less support, more formal supervision, little or no involvement in decisions, and less trust and attention from the leader” (Lussier & Achua, 2007), p. 254).

Whether an individual follower is in a high-quality or low-quality LMX relationship really has a strong impact on their view towards the organization itself. Followers in high-quality LMX relationships (also referred to as in-groups) have higher perceptions of leader credibility and a greater regard for their leaders compared to those followers in low-quality LMX relationships (also referred to as out-groups). Not only does the nature of the relationship impact a follower’s perceptions of her or his leader, but research has shown that high-LMX relationships lead to greater productivity, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment (Gagnon & Michael, 2004). Overall, research has shown many positive benefits for followers who have high-LMX relationships including:

- More productive (produce higher quality and quantity of work);

- Greater levels of job satisfaction;

- Higher levels of employee motivation;

- Greater satisfaction with immediate supervisor;

- Greater organizational commitment;

- Lower voluntary and involuntary turnover levels;

- Greater organizational participation;

- Greater satisfaction with the communication practices of the organization;

- Clearer understanding about her or his role within the organization;

- Greater exhibition of organizational citizenship behaviors;

- Greater long-term success in one’s career;

- Greater organizational commitment;

- Receive more desirable work assignments; and

- Receive more attention and support from organizational leaders.

One of the big questions that has arisen in the leadership literature is “how do leaders select followers to enter into a high-LMX relationship.” One possible explanation for why leaders choose some followers and not other followers for high-LMX relationships stems from the follower’s communication style. In a 2007 study, researchers examined the relationship between follower communication and whether or not they perceived themselves to be in a high-LMX relationship with their immediate supervisor (Madlock, Martin, Bogdan, & Ervin, 2007). Not surprisingly, individuals who reported higher levels of assertiveness, responsiveness, friendliness, cognitive flexibility, attentiveness, and a generally relaxed nature were more likely to report having a high-LMX relationship. One variable that was negatively related to the likelihood of having a high-LMX relationship was a follower’s level of communication apprehension.

Transformational Approach

The final approach to leadership is one that clearly is popular among organizational theorists. Although the term “transformational leadership” was first coined by James Downtown in 1973, the term was truly popularized by political sociologist James MacGregor Burns in 1978. In a 2001 study conducted by Kevin Lowe and William Gardner, the researchers examined the types of articles that had been published in the premier academic journal on the subject of leadership, Leadership Quarterly. The researchers examined the types of research published in the journal over the previous ten years, which found that one-third of the articles published within the journal examined transformational leadership.

To help understand leadership from this approach, it’s important to understand the two sides of leadership: transactional and transformational leadership. On the one hand you have transactional leadership, which focuses on an array of exchanges that can occur between a leader and her or his followers. The most obvious way transactional leadership is seen in corporate America is the use of promotions and pay raises. Transactional leaders offer promotions or pay raises to those followers who meet or exceed the leader’s goals. Rewards are seen as a tool that a leader utilizes to get the best performance out of her or his followers. If the rewards no longer exist, followers will no longer have the external motivation to meet or exceed goals.

Transformational leadership, on the other hand, can be defined as the “process whereby a person engages with others and creates a connection that raises the level of motivation and morality in both the leader and the follower” (Northhouse, 2007, p. 176). In essence, transformational leadership is more than just getting followers to meet or exceed goals because the leader provides the followers rewards. Bernie Bass proposed a more complete understanding of transformational leadership and noted three factors of transformational leadership: charismatic and inspirational leadership, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration(Bass, 1985a; Bass, 1985b).

Charismatic and Inspirational Leadership

The first factor Bass (1985a) described for transformational leaders was charismatic and inspirational leadership. Charisma is a unique quality that not everyone possesses. Those who are charismatic have the ability to influence and inspire large numbers of people to accomplish specific organizational goals or tasks. Where the transactional leader rewards followers for accomplishing tasks, transformational leaders inspire their followers to accomplish goals and tasks with no promise of rewards. Instead, followers are inspired by a transformational leader to accomplish goals and tasks because they share the leader’s vision for the future. Bass (1998) later made inspirational motivation a unique factor unto itself to clearly separate its impact from charismatic leadership.

Intellectual Stimulation

The second characteristic of transformational leaders is intellectual stimulation. In essence, transformational leadership “stimulates followers to be creative and innovative and to challenge their own beliefs and values as well as those of the leader and the organization” (Northhouse, 2007, p. 183). While both transactional and transformational leaders engage in intellectual stimulation themselves, the purpose of this intellectual stimulation differs. Transactional leaders tend to focus on how best to keep their organizations and the systems within their organizations functioning. Very little thought to innovation or improving the organization occurs because transactional leaders focus on maintaining everything as-is. Transformational leaders, on the other hand, are always looking for new and innovative ways to manage problems. As such, they also encourage those around them to “think outside the box” in an effort to make things better.

Individualized Consideration

The last factor of transformational leadership is individualized consideration, or seeing followers as individuals in need of individual development. Transformational leaders evaluate “followers’ potential both to perform their present job and to hold future positions of greater responsibility. The leader sets examples and assigns tasks on an individual basis to followers to help significantly alter their abilities and motivations as well as to satisfy immediate organizational needs” (Bass, 1985a, p. 35). The goal of this individualized consideration is to help individual followers maximize their potential, which maximizes the leader’s use of her or his resources at the same time.

Key Takeaways

- The trait approach to leadership is the oldest approach to leadership and theorizes that certain individuals are born with specific personality or communication traits that enable leadership. As such, trait leadership scholars have examined thousands of possible traits that may have an impact on successful or unsuccessful leadership practices.

- The situational approach to leadership focuses on specific organizational contexts or situations that enable leadership. Fred Fiedler’s Contingency Theory examines an individual’s preference for either task or relationships and then theorizes that leaders who find themselves in situations that favor that type of leadership will be fine while leaders who are out of balance need to either change the situation or adjust their leadership styles. Paul Hersey and Kenneth Blanchard’s Situational Leadership Theory, on the other hand, examines how leadership is dependent upon whether a follower is someone being developed or someone who has already been developed. New followers, Hersey and Blanchard theorize, need more guidance leaders should focus on the task and at hand and not on relationships with these followers. Old followers, on the other hand, need little guidance and little relationship building.

- The functional approach to leadership posits that a leader is someone who looks like, acts like, and communicates like a leader. Chester Barnard’s Functions of the Executive posits that leaders should engage in three specific functions: (1) formulating organizational purposes and objectives, (2) securing essential services from other members, and (3) establishing and maintaining a system of communication. A second functional approach is Kenneth Benne and Paul Sheats’ Classification ofFunctional Roles in Groups, which examines how different people take on various group/team roles in an effort to keep the group/team striving towards a specific goal. Each of the roles that group/team members take on serve a specific function in the group/team decision making and implementing process.

- The relational approach to leadership theorizes that leadership is a matter of building and maintain relationships with one’s followers. Robert Blake and Jane Mouton’s Managerial Grid examine the intersection of relationship-oriented or task-oriented leader perspectives. Ultimately, Blake and Mounton propose five distinct types of leadership: (1) impoverished (low task, low relational), (2) authority-compliance (high task, low relational), (3) country club (low task, high relational), (4) team (high task, high relational), and (5) middle-of-the-road (moderate task, moderate relational). A second relational approach is George Graen’s Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) Theory, which looks at the exchange relationship between a follower and a leader. Under LMX theory, leaders take on protégés into an interpersonal communicative relationship that enables a follower to succeed within an organization.

- The transformational approach to leadership espoused by James MacGregor Burns looks at leadership as a comparison to the traditional transactional model of leadership. In the transactional model of leadership, leaders promise to punish or reward followers in order gain support. Transformational leadership, on the other hand, occurs when a leader utilizes communication in an effort to increase follower morale, motivation, and performance to accomplish organizational goals.

Exercises

- Fill out the Least Preferred Coworker Scale (www.msubillings.edu/BusinessF…orkerScale.pdf). After completing the measure, what did you learn about your own approach to leadership? According to Contingency Theory, what leadership situations will you succeed in and what leadership situations will you need to alter either the situation or your own leadership behavior?

- Looking at Blake and Mouton’s Managerial Grid, which type of leadership style do you respond best to? Why do you think you respond best to this leadership style? Do you think you lead others in this fashion? Why or why not?

- Create a list of at least five transactional leaders and five transformational leaders. What differences do you see between thesetwo lists and the types of organizational accomplishments they’ve had?

References:

Barnard, C. I. (1938). The functions of the executive. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bass, B. M. (1985a). Leadership: Good, better, best. Organizational Dynamics, 13(3), 26-40.

Bass, B. M. (1985b). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York, NY: Free Press.

Bass, B. M. (1990). Bass and Stogdill’s handbook of leadership: Theory, research, and managerial applications (Rev. ed.). New York, NY: Free Press.

Bass, B.M. (1998). Transformational leadership: Industrial, military, and educational impact. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Benne, K. D., & Sheats, P. (2007). Functional roles of group members. Group Facilitation: A Research & Applications Journal, 8, 30-35. (Reprinted from the Journal of Social Issues, 4, 41-49).

Blake, R., & Mouton, J. (1964). The managerial grid: The key to leadership excellence. Houston, TX: Gulf Publishing.

Blake, R., & Mouton, J. (2011). The managerial grid. In W. E. Natemeyer & P. Hersey (Eds.), Classics of Organizational Behavior (4 ed., pp. 308-322). (Reprinted from The managerial grid: The key to leadership excellence. Houston, TX: Gulf Coast).

Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

de Vries, R. E., Bakker-Pieper, A., & Oostenveld, W. (2010). Leadership = communication? The relations of leaders’ communication styles with leadership styles, knowledge sharing and leadership outcomes. Journal of Business Psychology, 25, 367-380.

Dinh, J. E., & Lord, R. G. (2012). Implications of dispositional and process views of traits for individual difference research in leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 23(4), 651-669.

Downton, J. V. (1973). Rebel leadership: Commitment and charisma in the revolutionary process. New York, NY: Free Press.

Fiedler, F. E. (1967) A theory of leadership effectiveness. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Gagnon, M. A., & Michael, J. H. (2004). Outcomes of perceived supervisor support for wood production employees. Forest Products Journal, 54, 172-178.

Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 6, 219-247.

Hackman, M. S., & Johnson, C. E. (2009). Leadership: A communication perspective (5 ed.). Long Grove, IL: Waveland.

Hersey, P., & Blanchard, K. H. (1969). Life cycle theory of leadership. Training and Development Journal, 23(5), 26–34.

Hersey, P., Blanchard, K. H., & Johnson, D. E. (2000). Management of organizational behavior: Leading human resources (8th ed.). Upper Saddle, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Infante, D. A., & Rancer, A. S. (1982). A conceptualization and measure of argumentativeness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 46, 72-80.

Infante, D. A., & Wigley, C.J. (1986). Verbal aggressiveness: An interpersonal model and measure. Communication Monographs, 53, 61-69.

Limon, M. S., & La France, B. H. (2005). Communication traits and leadership emergence: Examining the impact of argumentativeness, communication apprehension, and verbal aggressiveness in work groups. Communication Quarterly, 70, 123-133.

Lowe, K. B., & Gardner, W. L. (2001). Ten years of the Leadership Quarterly: Contributions and challenges for the future. Leadership Quarterly, 11, 459-514.

Lussier, R. N., & Achua, C. F. (2007). Leadership: Theory, application, skill development (3 ed.). Mason, OH: Thomson/South-Western.

Kirkpatrick, S. A., & Locke, E. A. (1991). Leadership: Do traits matter? The Executive, 5, 48-60.

Madlock, P. E., Martin, M. M., Bogdan, L., & Ervin, M. (2007). The impact of communication traits on leader-member exchange. Human Communication, 10, 451-464.

Mann, R. D. (1959). A review of the relationship between personality and performance in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 56, 241-270.

McCroskey, J. C. (1984). The communication apprehensive perspective. In J. A. Daly & J. C. McCroskey (Eds.), Avoiding communication: Shyness, reticence, and communication apprehension (pp. 13-38). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Northhouse, P. G. (2007). Leadership: Theory and practice (4 ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; pg. 176.

Shane, S. (2010). Born entrepreneurs, born leaders: How your genes affect your work life. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Stogdill, R. M. (1948). Personal factors associated with leadership: A survey of the literature. Journal of Psychology, 25, 35-71.

Wrench, J. S. (2013). How strategic workplace communication can save your organization. In J. S. Wrench (Ed.), Workplace communication for the 21st century: Tools and strategies that impact the bottom line: Vol. 2. External workplace communication (pp. 1-37). Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Zaccaro, S. J. (2007). Trait-based perspectives of leadership. American Psychologist, 62(1), 6-16.