5.2 Formal Communication Networks

Learning Objectives

- Explain Weber’s (1930) beliefs on downward communication.

- Understand Katz and Kahn’s (1966) typology of downward communication.

- Clarify Hirokawa’s (1979) two problems associated with downward communication.

- Be able to explain Hirokawa’s (1979) four functions of upward communication.

- Understand Katz and Kahn’s (1966) typology of upward communication.

- Explain the importance of employee silence and organizational dissent.

- Explain Fayol’s (1916/1949) perspective on horizontal/lateral communication.

- Understand Hirokawa’s (1979) four functions of horizontal/lateral communication.

- Analyze Charles and Marschan-Piekkari’s (2002) five organizational behaviors to increase the quality and quantity of horizontal/lateral communication in multinational corporations.

The word “formal” describes adherence to a set of conventional requirements of behavior. Formal communication then consists of the rules and norms established by an organization for communicative behavior. A communication rule is a standard or directive governing how communication occurs within an organization.

Communication rules are explicitly stated and may be found in your organization’s policies and procedures manual. For example, maybe your organization has very strict policies established for what happens in case of an emergency. One of the authors of this book worked in a hospital that had very explicit communication rules if someone was accidentally stuck by a needle. First, the individual was required to immediately go to the emergency room for testing and the initiation of preventative pharmaceutical measures. Second, the head of the hospital’s risk management office was to be contacted. The risk management head would then investigate the matter and submit a formal report of all accidents to the CEO of the hospital on a monthly basis. These steps were not perceived as optional at all and were clearly written in the employee handbook. Communication norms, on the other hand, are standards or patterns of communication regarded as typical. Where communication rules are explicitly discussed within an organization, communication norms are only learned through active observation of communicative behavior within the organization. In fact, one of the most common ways to learn a communicative norm in an organization is to accidentally violate the norm. For example, in the same hospital discussed above, the head of risk management had to formally communicate to the CEO on a monthly basis any accidents that had occurred. However, the head of risk management would also send the CEO an e-mail as soon as she had an incident report just to keep him updated more frequently. When the head of risk management went on a two month leave of absence, one of her subordinates took over the position. The subordinate followed the guidelines as set forth in the policies and procedures manual to the letter. However, the CEO got very angry when at the end of the month he received his formal briefing of accidents because he hadn’t been kept up-to-date throughout the month. In this case, the subordinate had followed the formal communication rules of the organization but had violated what had become a formal communication norm.

Obviously, understanding how formal communication functions within an organization is very important, which is why a considerable amount of the early research on organizational communication examined formal communication. To help us further understand formal communication in the organization, we’re going to look at it by examining the three directions communication happens within an organization: downward, upward, horizontal/lateral.

Downward Communication

Downward communication consists of messages that start at the top of the hierarchy and are transmitted down the hierarchy to the lowest rungs of the hierarchy. Downward communication can be considered a top-to-bottom approach for organizational communication. The earliest thinker in the area of downward communication was Max Weber (1930). Weber believed that there were two ways to get employees to follow one’s directives: power and authority. Weber defined power as the ability to force people to obey regardless of their resistance, whereas authority occurs when orders are voluntarily obeyed by those receiving them. Weber argued that individuals in authority based organizations were more likely to perceive directives as legitimate. While this process sounds simplistic, individuals in management positions have often had to determine how to communicate with employees. Randy Hirokawa (1979) noted that there are two general types of downward communication in modern organizations:

(1) information concerning the current/future status of specific aspects of the organization, new organizational policies, recent administrative decisions, and recent changes in the standard-operating-procedures; and (2) information of a task-related nature which generally provide subordinates with the technical know-how to accomplish their tasks or assignments with greater efficiency and productivity. (p. 84)

While Hirokawa’s two-prong approach to downward communication is fairly consistent with the type of communication that occurs in modern organizations, this type of communication was not always present.

History of Downward Communication

C. J. Dover (1959) traced the history of downward communication through the utilization of employee publications. Dover’s research ultimately identified three distinct eras: entertainment, information, and interpretation and persuasion.

The Era of Entertainment

The first era of downward communication noted by C. J. Dover was the era of entertainment, which he defined as the period prior to World War II. In addition to basic directives, most of the communication during the Era of Entertainment was primarily fluff material, “company publications thus dealt largely with choice items of gossip, social chit-chat about employees, notices of birthdays and anniversaries, jokes, notices of local recreation and entertainment opportunities, etc” (Dover, 1959, p. 168). When one looks at this list of information communicated downward, the obvious lack of information about the state of the organization itself is glaring. However, “there were occasional exhortations to lead clean, moral, and thrifty lives, some attacks on the evils of ‘demon rum,’ some attacks on the ‘bolsheviks,’ [sic] and some printed resistance to early attempts at unionization” (Dover, 1959, p. 168).

The Era of Information

The second era of downward communication discussed by C. J. Dover was the era of information, which occurred during the 1940s. Two competing forces ultimately changed the face of employee communication during the 1940s. First, businesses were forced to produce more with less as a result of the U.S. entry into World War II after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. As businesses found themselves with less overhead capital, the printing of company publications with trivial, entertaining information became a non-necessity. Second, research in the social sciences started to ascertain that informed employees were more productive employees. Ultimately, this second issue won out and employee publications started to focus more on information about the organization and less on the entertainment value of the publications. In fact, the number of employee publications tripled from 1940 (2,000) to 1950 (6,000). These new publications were very different from their pre-WWII precursors, “The new emphasis in content was on informing employees about the company—its plans, operations, and policies. Typical of this new material were reports on company growth, and expansion, the outlook for the business and the industry, company financial reports, and information on productivity, costs, and employee benefit plans” (Dover, 1959, p. 169).

The Era of Interpretation and Persuasion

The third era of downward communication discussed by C. J. Dover was the era of interpretation and persuasion, which occurred during the 1950s. During the 1950s employee publications maintained their entertainment and information aspects, but added an organization’s perspective on information in an attempt to interpret the information and persuade the employee’s to the organization’s interpretation. Dover (1959) had this to say about interpretation and persuasion:

The “Era of Interpretation and Persuasion” adds new features [to employee publications]. Prominent among these are (a) interpretation—i.e., emphasizing or explaining the significance of the facts in terms of employee or reader interest, and (b) persuasion—i.e., urging employees or readers, on the basis of the facts as they have been interpreted, to take specific action or to accept management’s honest ideas and opinions. (p. 170)

Managers to this day still attempt to communicate to their employees using interpretative and persuasive strategies. The rest of this section is going to examine types of downward communication, problems with downward communication, and effective methods for downward communication.

Types of Downward Communication

While there are numerous typologies examining the various types of messages transmitted down a hierarchy from management, the most commonly cited typology was created by Daniel Katz and Robert L. Kahn (1966). Katz and Kahn’s typology breaks downward communication into five distinct types: job instructions, job rationales, procedures and practices, feedback, and indoctrination.

Job Instructions

The first type of message that management commonly communicates to employees are job instructions, or how management wants an employee to perform her or his job. Often this type of downward communication occurs through training. Depending on the difficulty of the job, communicating to an employee how to perform her or his job could take days, months, or years. Some organizations will even send employees outside of the organization for more specialized training.

Job Rationales

The second type of messages Katz and Kahn (1966) identified as commonly communicated downward in an organization are job rationales. A job rationaleA basic statement of the purpose of a specific job and how that job relates to the overarching goal of the organization. is a basic statement of the purpose of a specific job and how that job relates to the overarching goal of the organization. Every job should help the organization achieve its goals, so understanding how one’s position fits into the larger scheme of the organization is very important. Furthermore, the job rationale will also illustrate how a single job relates to other jobs within the organizational hierarchy.

Procedures and Practices

The third type of messages Katz and Kahn (1966) identified as commonly communicated downward in an organization are procedures and practices. Procedures and practices typically come in the form of an employee manual or handbook when you start working within an organization. Procedures are sequences of steps to be followed in a given situation. For example, in an organization, there may be procedures in place for reporting sexual harassment or procedures for hiring new members. PracticesBehaviors people should do habitually., on the other hand, are behaviors people should do habitually. For example, maybe you are required to punch in and out using a time-clock or you are not allowed to wear open toed shoes. There are procedures and practices related to policies (courses of action taken in the organization), rules (standards or directives governing behavior), and benefits (payment and entitlements one receives with the job).

Feedback

The fourth type of message Katz and Kahn (1966) identified as commonly communicated downward in an organization is feedback. Providing feedback to one’s subordinates is a very important feature of any supervisory position (Redding, 1972). Employees can only grow and become more proficient with their jobs if they are receiving feedback from those above them. This feedback needs to contain both positive and negative feedback. Positive feedback occurs when a supervisor explains to a subordinate what he or she is doing well, whereas negative feedback occurs when a supervisor explains to a subordinate areas that need improvement. Furthermore, feedback should not only occur in formal review sessions often referred to as “summative feedback.” Instead, supervisors should utilize formative feedback, or periodic feedback designed to help an employee grow and develop within the organization.

Employee Indoctrination

The last type of downward communication discussed by Katz and Kahn (1966) is employee indoctrination. Indoctrination is the process of instilling an employee with a partisan or ideological point of view. Specifically, organizations use indoctrination messages in order to help new members adopt ideological stances related to the organization’s culture and goals. The ultimate goal of organizational indoctrination is organizational identification, or “the extent to which that person’s self-concept includes the same characteristics he or she perceives to be distinctive, central, and enduring to the organization” (Beyer. Hannah, & Milton, 2000, p. 333).

Katz and Kahn’s (1966) typology of downward communication is very useful to remember when examining how communication in an organization is conducted. Often, managers may be competent at one or two of the types of downward communication but not as competent in the other three. When this is the case, managers need training in how to become effective downward communicators. Furthermore, managers must also think of the most appropriate communication channels to use when sending downward messages. An article in Management Report in 2004 titled “Downward Communication” listed a wide range of possibilities for communicating information downward: staff meetings, one-on-one meetings, internal newsletters, employee information sheets, bulletin boards, employee handbooks, and e-mail. While all of these are options for downward communication, not all of them appropriate for every communication situation. For example, you probably don’t want to chastise an employee’s tardiness in a company newsletter, on a bulletin board, or during a staff meeting, however this form of downward communication could be appropriately sent during a one-on-one meeting, through employee information sheets, or in an e-mail. Ultimately, managers must be competent in how they communicate down the hierarchy to their subordinates. Now that we’ve looked at the types of messages sent down the hierarchy and the different mediums a manager could use to send messages down the hierarchy, let’s examine some of the problems with downward communication.

Problems with Downward Communication

Downward communication is an extremely important part of any organization. However, Randy Hirokawa (1979) noted that there are two primary problems associated with downward communication: accuracy and adequacy. Accuracy of information refers to how truthful a message is that has been received. There are two primary ways that the accuracy of a message can be distorted. First, some messages are simply based on inaccurate information. For example, a manager who hears a false rumor and then passes the rumor on to her or his subordinates has passed on inaccurate information. Obviously, when the truth of the rumor is learned by subordinates, the manager’s credibility is going to be negatively impacted because her or his subordinates will perceive the manager as not being a trustworthy source of information. The second way messages can contain inaccurate information is as a result of multiple people in the communication chain, or as W. Charles Redding (1966) calls it serial transmission. As we know from playing the telephone game in school, when A communicates to B and B communicates to C and C communicates to D, the chances of the message becoming distorted with each passing person becomes more likely. Even in the case of serial transmission of information (A→ B → C → D) managers who are caught communicating inaccurate information can expect to have employees question their credibility. Another ramification of passing on inaccurate information is that some subordinates will start to question how connected their supervisor is to the organizational hierarchy. Basically, if my supervisor is passing on inaccurate information, then clearly he or she doesn’t really know what’s going on at all.

A second problem associated with downward communication refers to the adequacy of the information being communicated. Adequacy of informationWhether or not the information being communicated is sufficient to satisfy a requirement or need for information in the workplace. refers to whether or not the information being communicated is sufficient to satisfy a requirement or need for information in the workplace. When discussing adequacy, there are two possible extremes that managers could swing to: communication underload and communication overload. Communication underload occurs when subordinates are not provided enough information to complete their jobs. Communication underload can come in the form of inadequate on-the-job training, limited feedback from one’s supervisor, or insufficient information on policies and procedures in the organization. Often communication underload is completely accidental and occurs as an inadvertent omission. In this case, supervisors themselves may have too many things going on and information is accidentally not passed on to their subordinates in a timely fashion or at all. Other times communication underload can occur because a supervisor feels the need to hoard information in an effort to secure her or his power base. Individuals often see information as power and transmitting that information to another person as a loss of power (Huseman, Lahiff, & Wells, 1974). When information hoarding occurs, subordinates may be given just enough information to not make their supervisor look bad, but not enough information to truly excel at their jobs. For obvious reasons, information hoarding can be a very large problem in organizations.

The second problem associated with adequacy of information involves communication overload, or when subordinates are provided too much information to complete their jobs. In an ideal work environment, supervisors will function as gatekeepers of information and make sure that adequate information is passed on to a subordinate to help the subordinate excel in her or his job. Unfortunately, some supervisors do not know how to function as gatekeepers, so they pass along any information they receive to their subordinates without filtering information that is not useful for their subordinates. Eventually, subordinates can become so overwhelmed with the number of messages that are being received, that they spend much of their work day simply shifting through information, which decreases their ability to be productive (Anderson & Level, 1980). Other individuals when faced with communication overload simply start ignoring all of the information coming in because it’s simpler to just ignore information than to shift through it all. Communication overload is generally a product of channel capacity or an individual’s limits to receiving information (Redding, 1972). Some information is easy for an individual process, but other information involves considerable more effort on the part of the receiver. The more technical and complex the information, the smaller an individual’s channel capacity for handing the information will be.

In addition to Randy Hirokawa’s (1979) two primary problems associated with downward communication, we believe there is a third problem with downward communication: utility. Utility involves whether or not the information provided is actually useful. Often information that is transmitted to an individual within an organization is completely useless to that individual. For example, one of the coauthors of this book was paid to go to a meeting about new computer software the organization wasn’t planning on purchasing. In this instance, the subordinate (our coauthor) was actually sent for training on a software package that the subordinate would never see and never use. In this case, our coauthor not only wasted time going to this meeting, the organization paid our coauthor to actually go to this meeting and the organization paid the person making the presentation. In essence, both time and money were wasted on information that had no utility to either the individual employee or the organization.

Effective Methods for Downward Communication

So now that we’ve looked at some of the problems organizations face with downward communication, let’s examine some best practices for downward communication. First, individuals who are engaged in downward communication need to make sure that the information they are passing on to those below them is first, and foremost, accurate. If this means spending a little extra time verifying information, then verify the information. A supervisor may have to spend a couple of extra minutes verifying information, but this is a better trade-off than having to rebuild one’s credibility.

Second, make sure that the amount of information you are passing along to your subordinates is adequate and can be utilized. To ensure that you are avoiding communication underload and communication overload, you should do two things: filter and ask. The first thing to ensure your subordinates are receiving adequate information is filter out information that isn’t necessary for your subordinates. Filtering out information for one’s subordinates is not an easy task. One easy way to help filter information is to ask yourself, “will this information help my subordinates personally or professionally.” Some information could help your subordinates personally—workshops on avoiding stress, time management, or conflict management. While other information can help your subordinates professionally: information related to job duties, information on career advancement, and information related to organizational policies and procedures. In addition to attempting to filter information for your subordinates, you can always ask your subordinates if they feel they are getting enough information. Often subordinates will be the first to tell you when they feel under or over informed.

The third best practice in downward communication involves the source of the message. Obviously, the source of the message has a strong impact on how people interpret the importance of the message itself. For example, messages received from the CEO of organization will receive more weight than a message from a mid-level manager. For this reason, important messages should come from the top of the hierarchy and be transmitted as directly as possible to the employees to avoid serial transmission.

The fourth best practice in downward communication involves the type of communication channels utilized for the downward transmission of a message. By communication channels, we are referring to the traditional notion of communication channels commonly held in organizations. When encoding a message for transmission through the organizational hierarchy, one needs to think about the most expedient method for delivering the message itself. As previously discussed, the more individuals a message is transmitted through will increase the likelihood that the message itself will become distorted.

The fifth best practice in downward communication involves mindfully picking the communicative medium utilized for downward communication. As discussed earlier in this chapter, Katz and Kahn’s (1966) typology of downward communication consists of five different types: job instructions, job rationales, procedures and practices, feedback, and indoctrination. When encoding various messages related to these five types of downward communication, managers need to realize that the same communicative medium may not be the most effective tool for every message communicated. There are a variety of different types of communicative mediums that could be utilized: staff meetings, one-on-one meetings, internal newsletters, employee information sheets, bulletin boards, employee handbooks, e-mail, employee social networking sites, etc… In fact, if a piece of information is extremely important, communicating the information through multiple mediums may also be important. One of our coauthors had a former student named Chad who worked for a large discount chain as a front-line customer services representative in the technology department. Chad found out one day that he had violated a new rule set forth by the organization that he didn’t know existed. When he asked his manager about the new policy, Chad was told that the he should have received an e-mail about the new rule in his employee e-mail account. To make this situation even more problematic, Chad didn’t even know that he had an employee e-mail account. Chad discovered that the corporation had an intranet and all employees were supposed to check their e-mail prior to clocking-in for work. Chad asked some of his coworkers if they knew about employee e-mail accounts and found that no one apparently knew about the e-mail accounts. This example illustrates what can happen when organizations only utilize one communicative medium for important downward messages.

The story about Chad also illustrates our final recommendation for best practices in downward communication, checking for understanding. The message received, not the one sent, is the one that a receiver will ultimately act upon in an organization (Redding, 1972). Or as in the case of Chad, the lack of message reception is also a problem. It’s one thing to tell someone something, and completely different to have communicated with someone. Telling is a sender centered communicative strategy because the sender encodes a message and transmits the message (Richmond, McCroskey, & McCroskey, 2005). However, the sender does not make sure that a receiver actually receives the message or correctly interprets the message itself. Furthermore, the meaning of a message is one that is determined by the receiver not by the sender (Redding, 1972). In the case of telling, the receiver is completely taken out of the communication process, so the chance of misunderstandings and missed communication increases dramatically. For this reason, we recommend that downward communication be followed up by some kind of interaction with the individuals being sent a message to ensure that the message is being received and interpreted in a manner consistent with the sender’s original intent. To ascertain message reception and interpretation, supervisors need to encourage their subordinates to participate in upward communication.

Upward Communication

Upward communication consists of messages that start at the bottom of the hierarchy and are transmitted up the hierarchy to the highest rungs of the hierarchy. Upward communication can be considered a bottom-up approach to organizational communication. Randy Hirokawa (1979) noted that upward communication serves four very important functions in the modern organization. First, upward communication allows management to ascertain the success of previously relayed downward communication. Second, upward communication allows individuals at the bottom of the hierarchy to have a voice in policies and procedures. Hirokawa (1979) clarifies, “Perhaps even more importantly, upward communication, because it allows subordinates to participate in the decision-making process, also facilitates the acceptance of those decisions which they had a part in making” (p. 86). Third, upward communication allows subordinates to voice suggestions and opinions to make the working environment better. As Elton Mayo (1933) discovered during the employee interview program as part of the Hawthorne Works Studies, employees have a lot to say about their working conditions and how to make the organization more efficient. Furthermore, simply asking employees for their suggestions and opinions was found to increase job satisfaction. Lastly, upward communication allows management to test how employees will react to new policies and procedures. Often before radical changes are made to an organization, management will try to use focus groups of subordinates to gage their reactions to impending changes. These reactions can then be used in the framing of the communicative messages about the impending changes to the entire organization.

As a side note, we feel it is important to also stress research examining sex differences in upward communication (Stewart, Stewart, Friedley, & Cooper, 1996). The researchers noted females who provide more upward communication are more likely to advance and be promoted than those females who did not. As such, in a world where women are still under-promoted in many organizations, mastering upward communication can be very important for female workers. Now that we’ve examined some of the basic reasons for upward communication in organizations, we’re going to examine the types of upward communication in organizations, problems with upward communication in organizations, and effective methods for upward communication.

Types of Upward Communication

While there are numerous typologies examining the various types of messages transmitted up a hierarchy, the most commonly cited typology was created by Katz and Kahn (1966). Katz and Kahn’s (1966) typology breaks upward communication into four distinct types: information about the subordinate her/himself, information about coworkers and their problems, information about organizational policies and procedures, and information about the task at hand. Dennis Tourish and Paul Robson (2006) argue that a fifth form of upward communication needs to be included in this list: critical upward communication.

Information about the Subordinate

The first form of upward communication discussed by Katz and Kahn (1966) involves information about the subordinate her or himself. Information that can be communicated upwardly about oneself typically falls into one of two categories: personal information and professional information. Personal information that can be communicated upwardly involves information that is more intimate in nature. For example, you can talk to your supervisor about your friends and families, hobbies, psychological/medical problems, etc…. This information helps subordinates establish a more understanding relationship with their supervisors. Professional information that can be communicated upwardly involves issues related to job performance or problems related to work. For example, maybe you’re having a great quarter and want to communicate this to your supervisor. On the other hand, maybe you’re really having problem with one specific facet of your job and you need help or more time. Perhaps you’re supposed to write a report, but the report keeps getting pushed further and further down your priority list as new projects come your way.

Information about Coworkers and their Problems

The second form of upward communication discussed by Katz and Kahn (1966) involves information about coworkers and their problems. Often managers are completely removed from what is actually going on with their subordinates because the managers’ attentions are not completely focused on their subordinates. Despite what subordinates often think, managers have their own workloads that must be taken care of in addition to their managerial duties. For this reason, managers are often simply unaware of what is going on with their subordinates. In order to combat this lack of clarity, managers often rely on subordinates to report problems. One of our coauthors worked for a medical school overseeing medical students, interns, residents, and teaching faculty. One of the medical interns was actually showing up to work intoxicated. The only reason our coauthor found out about this was when one of the teaching faculty called to report the problem. While it was our coauthor’s job to oversee situations like these, if our coauthor had never been told there was a problem, the problem would have continued and could have led to serious consequences both medically and legally. Another facet of this problem occurs when subordinates are not able to complete their job duties. People can become very adept at hiding what they don’t know and can’t do when necessary. While others will only actively work when they are under immediate supervision, however once the supervision leaves, the individuals stop working. The only way a supervisor can have any chance of finding out about either one of these situations is to rely on other subordinates to report what’s happening. While children are taught that tattle-telling is a horrible thing, often telling a supervisor what a coworker is or is not doing is extremely important. Whether the coworker simply needs more training or needs to be reprimanded, the only way a supervisor can correct behavior is if he or she knows about the problem in the first place. To help with this process, many organizations have actually initiated anonymous complaint/report phone lines. Individuals who see someone behaving in a dangerous or unethical manner can anonymously call the phone line and leave a message about the problem, and the organization can then start its own internal investigation.

Organizational Procedures and Practices

The third form of upward communication discussed by Katz and Kahn (1966) involves information about organizational procedures and practices. As previously discussed in this chapter, procedures are sequence of steps to be followed in a given situation, whereas practices are behaviors people should do habitually. Within any organization there are procedures and practices related to policies (courses of action taken in the organization), rules (standards or directives governing behavior), and benefits (payment and entitlements one receives with the job). Upward communication about procedures and practices can help management see where policies, rules, and benefits can be more influential or stream-lined. Often, management creates procedures and practices for how things ought to be accomplished without ever having to implement the procedure or practice themselves. The only way management can know if the procedures and practices are causing unneeded stress or loss of resources is if the people who have to enact those procedures and practices explain the problem.

Task at Hand

The last form of upward communication discussed by Katz and Kahn (1966) involves information about the task at hand. This last form of upward communication is specifically directed to communicate information to management that helps an individual complete her or his job. Types of messages that could fall into this category include asking for more information, asking to have a task clarified, asking for additional resources to complete the task, keeping a supervisor informed of a time table for completion, explaining the current status of a project, etc…. All of these different types of messages enable the subordinate to either ask questions about the task or inform their supervisor about the task. While communicating information about oneself is probably most important during the initial stages of relationship development with one’s supervisor, communicating information about tasks to one’s supervisor is the most common form of upward communication and the most important over time.

Critical Upward Communication

In addition to the four forms of upward communication discussed already, Tourish and Robson (2006) argue that a 5th form of upward communication needs to be included in this list: critical upward communication. Critical upward communication is “feedback that is critical of organizational goals and management behavior” (Tourish, & Robson, 2006, p. 711). Critical upward communication has been discussed under many different terms, “employee voice, issue selling, whistle-blowing, championing, dissent and boat rocking” (Tourish, & Robson, 2006, p. 712). Everyday individuals in organizations around the world make decisions about whether to communicate critically about organizational goals and management behavior. To help us understand upward communication, let’s briefly examine two communication related variables: employee silence and organizational dissent.

Employee Silence

A lot of the focus in communication research is on talking, but Richard Johannesen (1974) explained that researchers needed to start understanding the vital role that silence can play in human communication within a variety of contexts. The first researchers to examine the impact silence can have in the workplace in the organizational literature were Elizabeth Morrison and Frances Milliken (2000). Employee silence is fundamentally understood as a communication phenomenon where employees intentionally or unintentionally withhold information that might be useful to a leader or her or his organization. Morrison and Milliken argued that employees remain silent because of their manager’s behavior with regards to upward communication. Specifically, “silence is an outcome that owes its origins to (1) managers’ fear of negative feedback and (2) a set of implicit beliefs often held by managers” (Morrison & Milliken, 2000, p. 705). Imagine you’re working in a pizza shop and you try to explain to your manager that simply rearranging some of the ingredients would actually make putting the pizza together faster. If the manager shoots you down or gives you dirty looks at the suggestion, you will be less likely to offer advice in the future.

There are three common forms of employee silence: acquiescent silence, defensive silence, and prosocial silence (Van Dyne, Ang, & Botero, 2003). First, acquiescent silenceForm of employee silence that occurs when employees are disengaged in the workplace and feel they simply cannot make difference. occurs because employees are disengaged in the workplace and feel they simply cannot make difference. As such, they withhold information or simply do not bother offering suggestions because they believe that it is impossible to make a real difference in their organization. Second, defensive silenceForm of employee silence that occurs when an employee believes that speaking up will put her or him at risk, so the employee opts to not speak out. occurs as a form of self-protection for employees. If an employee believes that speaking up will put her or him at risk, then that employee will be less likely speak up. These people withhold information or omit facts because they fear some kind of organizational retaliation. Lastly, prosocial silenceForm of employee silence that occurs because employees want to appear cooperative and/or altruistic in the workplace. occurs because employees want to appear cooperative and/or altruistic in the workplace. Organizations where conflict is discouraged or avoid can lead people to withhold information to appear cooperative or protect “proprietary knowledge to benefit the organization” (Van Dyne, Ang, & Botero, 2003, p. 1363).

In a study examining employee silence in the workplace, Surahmaniam Tangirala and Rangaraj Ramanujam (2008) found that employees who were “silenced” in the workplace perceived their working environments as unjust, they did not identify with their organizations, and they did not professionally committed to their organizations. In another study by Jason Wrench (2012), he operationalized a set of theoretical items originally proposed by Morrison and Milliken into a research measure. In Wrench’s study, he set out to examine the relationship between organizational politics and various other organizational constructs. Specifically related to employee silence, Wrench found that acquiescent and defensive silence negatively related to employee motivation and job satisfaction. Conversely, prosocial silence positively related to employee motivation and job satisfaction. Overall, this study demonstrates the impact that silence can have on an individual’s happiness in the workplace.

While employee silence has received a lot of traction in academic circles since 2000, there are definitely a number myths about employee silence that have developed (Detert, Burris, & Harrsion, 2010):

- Myth: “Women and nonprofessional employees withhold more information than men and professional staffers because they are more concerned about consequences or more likely to see speaking up as futile.” Reality: Research has found no evidence that any of this is true. In fact, the studies that have examined gender differences have turned up no evidence to support that women and men utilize silence in the workplace to differing degrees. Furthermore, neither education nor income is also a good predictor of who will be silent.

- Myth: “If my employees are talking openly to me, they’re not holding back.” Reality: Research has found that 42% of people admit to purposefully withholding information when there is nothing to gain or something to lose by divulging that information (Detert, Burris, & Harrsion, 2010). As such, people may be talking but they may not be actually giving management a complete picture.

- Myth: “If employees aren’t speaking up, it’s because they don’t feel safe doing so, despite all my efforts.” While there are many employees who will remain silent out of fear, 25% of employees withhold information simply to avoiding wasting time (Detert, Burris, & Harrsion, 2010). Unfortunately, when employees make decisions on what is useful or non-useful information, those decisions may not be completely informed or accurate.

- Myth: “The only issues employees are scared to raise involve serious allegations about illegal or unethical activities.” Reality: Obviously, whistleblowing, the act of disclosing about an illegal or unethical activity, can definitely make people a little anxious. However, 20% of employees admit that “fear of consequences has led them to withhold suggestions for addressing ordinary problems and making improvements. Such silence on day-today issues keeps managers from getting information they need to prevent bigger problems” (Detert, Burris, & Harrsion, 2010, p. 26).

Overall, employee silence is a stifling behavior that has numerous negative effects on how people communicate and interact within the workplace. Let’s switch our attention to the other end of the communication spectrum and discuss how employees articulate dissent within the workplace.

Organizational Dissent

Jeffrey Kassing (1997) proposed a model for what he coined “organizational dissent” as having two basic processes: (1) individual employee feels apart from her or his organization, and (2) the employee expresses disagreement about some aspect of her or his organization’s philosophy or behavior. The second of these processes is similar to Tourish and Robson (2006) notion of critical upward communication. Kassing believed that dissent is a “subset of employee voice that entails the expression of disagreement or contradictory opinions in the workplace” (Kassing, 1998, p. 184). Ultimately, the concept of organizational dissent stems out of the basic American value of freedom-of-speech where it is promoted that good citizens should be able to express their disagreement. However, in the organizational realm, employees must carefully decide whether expressing disagreement is worth the possible ramifications of disagreeing, “employees assess available strategies for expressing dissent in response to individual, relational, and organizational influences and that they actually express dissent after considering whether they will be perceived as adversarial or constructive as well as the likelihood that they will be retaliated against” (Kassing, 1998, p. 191). Ultimately, Kassing (2011) argued that there are three primary types of organizational dissent: articulated/upward, latent/lateral, and displaced. Note the “Organizational Dissent Scale” below contains the scale created by Kassing to measure employee dissent.

Organizational Dissent Scale

Read the following questions and select the answer that corresponds with how you communicate in your workplace. Do not be concerned if some of the items appear similar. Please use the scale below to rate the degree to which each statement applies to you:

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

- I am hesitant to raise questions or contradictory opinions in my organization.

- I speak with my supervisor or someone in management when I question workplace decisions.

- I make suggestions to management or my supervisor about correcting inefficiency in my organization.

- I do not express my disagreement to management.

- I tell management when I believe employees are being treated unfairly.

- I bring my criticism about organizational changes that aren’t working to my supervisor or someone in management.

- I don’t tell my supervisor when I disagree with workplace decisions.

- I’m hesitant to question workplace policies.

- I do not question management.

- I complain about things in my organization with other employees.

- I join in when other employees complain about organizational changes.

- I share my criticism of this organization openly.

- I hardly ever complain to my coworkers about workplace problems.

- I let other employees know how I feel about the way things are done around here.

- I do not criticize my organization in front of other employees.

- I criticize inefficiency in this organization in front of everyone.

- I make certain everyone knows when I’m unhappy with work policies.

- I speak freely with my coworkers about troubling workplace issues.

SCORING: To compute your scores follow the instructions below:

- Articulated Dissent

- Step One: Add scores for items 2, 3, 5, & 6

- Step Two: Add scores for items 1, 4, 7, 8, & 9

- Step Three: Add 30 to Step One.

- Step Four: Subtract the score for Step two from the score for Step Three.

- Latent Dissent

- Step One: Add scores for items 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 17, & 18

- Step Two: Add scores for items 13 & 15

- Step Three: Add 12 to Step Two.

- Step Four: Subtract the score for Step two from the score for Step Three.

Interpreting Your Score

For articulated dissent, scores should be between 9 and 45. If your score is above 32, you are considered to engage in high amounts of articulated dissent. If your score is below 32, you’re considered to engage in minimal amounts of articulated dissent.

For latent dissent, scores should be between 9 and 45. If your score is above 25, you are considered to engage in high amounts of latent dissent. If your score is below 25, you’re considered to engage in minimal amounts of latent dissent (Kassing, 2000) .

Articulated/upward dissent “involves expressing dissent within organizations to audiences that can effectively influence organizational adjustment and occurs when employees believe they will be perceived as constructive and that their dissent will not lead to retaliation” (Kassing, 1998, pp. 191-192). Kassing (2002) further noted that there are five different types of dissent strategies subordinates can employ: direct-factual appeal, solution presentation, repetition, circumvention, and threatening resignation.

The first articulated dissent strategy is direct-factual appeal, which is when “people provide factual information based on their own work experience and their understanding of company policies and practices when they express their disagreement to their supervisors” (Kassing, 2005, p. 233).

The second articulated dissent strategy is solution presentation, which is when a subordinate offers a solution to a workplace problem while raising concerns about the problem itself.

The third articulated dissent strategy is repetition, or when a subordinate keeps raising the same issue over and over again over a period of time. The idea behind repetition is that if the problem is brought up over and over again, the supervisor may be more inclined to eventually do something about the problem.

The fourth articulated dissent strategy is circumvention, which is when a subordinate goes around her or his immediate supervisor to someone higher up the hierarchy in an attempt to get some kind of action taken. While circumventing one’s immediate supervisor can be very dangerous, there are often times when it is necessary. For example, many organizations have procedures for the reporting sexual harassment. The most common first step in sexual harassment procedures is to report any harassing behavior to your immediate supervisor, but what if your immediate supervisor is the one harassing you? Many organizations realize that supervisor harassment can be a problem, so they actually designate someone within the organization as the “go to” person for incidents of harassment. In these cases, individuals lower on the hierarchy are able to circumvent their supervisors and report the harassment to someone higher on the hierarchy.

The last articulated dissent strategy is to threaten resignation. This dissent strategy is fairly simple: do what I want or I quit. Of course, this dissent strategy is only effective if the person dissenting is actually ready to resign. Never use threatening resignation as a bluffing tactic because your supervisor may just decide to call your bluff.

The second type of organizational dissent, latent/lateral dissent, consists of communicative behaviors “that involves complaining to coworkers and voicing criticism openly within organizations” (Kassing, 1998, p. 211). Kassing (1998) labeled this form of dissent “latent dissent” because the term “suggests that dissent readily exists but is not always observable and that dissent becomes observable when certain conditions exists (i.e., when frustration mounts)” (p. 211). This form of organizational dissent is actually a form of horizontal or lateral organizational communication, which will be discussed later in this chapter.

Current Research—Kassing

Investigating the Relationship between Superior-Subordinate Relationship Quality and Employee Dissent

Kassing, J. W. (2000). Investigating the relationship between superior-subordinate relationship quality and employee dissent. Communication Research Reports, 17, 58–70.

In this study, Kassing set out to examine the relationship between subordinate-supervisor relationship quality and subordinate utilization of articulated and latent dissent. He recruited 232 employees who worked in various organizations throughout the state of Arizona. His sample consisted of 113 females (56%) and 99 males (43%) with 1% not responding to the question regarding biological sex. The mean age of the participants was 37.08 and the average length of time on their current job was 5.72 years. The study contained individuals at various levels of organizational hierarchies: 6% held top management positions, 30% held management positions, 57% held non-management positions, and 6% held other organizational positions.

In this study, Kassing had two basic hypotheses he wanted to test:

H1: Subordinates who perceive having high-quality relationships with their supervisors will report using significantly more articulated dissent than subordinates who perceive having low-quality relationships with their supervisors.

H2: Subordinates who perceive having low-quality relationships with their supervisors will report using significantly more latent dissent than subordinates who perceive having high-quality relationships with their supervisors.

To test these two hypotheses, Kassing used his measure of organizational dissent along with a measure of subordinate-supervisor relationship quality. Using the measure of subordinate-supervisor relationship quality, Kassing created two groups by taking those who scored above the median (indicating high relationship quality) and those who scored below the median (indicating low relationship quality). Kassing then examined if these two groups differed in their use of articulated and latent dissent.

The results for the first hypothesis indicated that those individuals who reported having high relationship quality with their supervisors were more likely to engage in articulated dissent than those who reported having low relationship quality with their supervisors. Ultimately, the first hypothesis was supported by the results.

The results for the second hypothesis indicated that those individuals who reported having low relationship quality with their supervisors were more likely to engage in latent dissent than those who reported having high relationship quality with their supervisors. Ultimately, the second hypothesis was supported by the results.

Based on the results from this study, we learn that the quality of relationship an individual has with her or his immediate supervisor has a direct impact on both articulated and latent organizational dissent.

The final type of dissent is referred to as displaced dissentForm of organizational dissent that occurs when an employee feels that dissent in the workplace could be harmful, so he or she express dissent to friends and family members outside the boundaries of the organization. and occurs outside of the confines of the organization itself. When an employee feels that dissent in the workplace could be harmful, he or she will often express dissent to friends and family members. Ultimately, whether an individual decides to express dissent within the organization (upward or lateral) depends on how he or she views the risks of doing so. If someone fears retaliation, bullying, or ostracism because of dissent, he or she will be less likely to engage in dissent within the workplace (Waldron & Kassing, 2011).

Research has also shown a relationship between employee silence and organizational dissent (Wrench, 2012). Specifically related to employee silence, Wrench found that acquiescent and defensive silence negatively related to articulated dissent and positively related to latent dissent. Conversely, prosocial silence positively related to articulated dissent and negatively related to latent dissent. Overall, this research demonstrates that there is a clear relationship between the use of silence within an organization and the way an employee expresses her or his dissent.

Problems with Upward Communication

Randy Hirokawa (1979) noted that there are two primary problems associated with upward communication: distortion and filtering. Researchers have found that 85 percent of individuals had on at least one occasion “felt unable to raise an issue or concern to their bosses even though they felt that the issue was important” (Milliken, Morrison, & Hewlin, 2003, p. 1459). In essence, subordinates purposefully do not communicate information to their supervisors, which ultimately distorts the overall picture a supervisor has of what is going on in the workplace. The first study conducted on the issue of upward distortion was Glen Mellinger’s (1956) ground breaking study on the subject. Fredric Jablin (1979) summarized Mellinger’s findings in this manner:

Results of this early inquiry into message distortion revealed that when Individual A does not trust Individual B, Individual A will conceal his/her feelings when communicating to B about a particular issue. Moreover, concealment of Individual A’s true feelings was found to be often associated with evasive, compliant, or aggressive communicative behavior on his/her part and with under- or overestimation of agreement on the issue by individual B. (pp. 1204–1205)

In essence, when a subordinate is not forthcoming with her or his thoughts on an issue, a supervisor often guesses what her or his subordinates think about the specific issue.

Now that we’ve examined Randy Hirokawa’s (1979) first problem associated with upward communication (distortion), we need focus on the “three possible culprits” of failure in upward communication: trust, influence, and mobility (Roberts & O’Reilly, 1974). The first reason why upward distortion may happen is because a subordinate doesn’t trust her or his supervisor. If a subordinate does not perceive her or his supervisor as trustworthy, the subordinate is simply more likely to avoid telling the supervisor anything other than absolutely necessary information. The second reason why upward distortion may occur is a result of subordinate perceptions of supervisor influence over subordinate’s future. Subordinates who perceive a supervisor as having a great effect on their futures could react in two totally different ways. Some subordinates will be very open with communication in an effort to build a stronger relationship with their supervisor, whereas other subordinates will actually go along with whatever a supervisor wants even if the subordinate thinks it’s a bad idea. In one case a subordinate could end up over communicating, while in the other case a subordinate ends up under communicating, either way you end up with upward distortion. The third reason for upward distortion relates to an individual’s desire to move up within the hierarchy. It’s one thing for a supervisor to have influence over your career path, and a completely different thing to either care or not care about mobility.

In one study the researchers examined four different organizations to see the effect of trust, influence, and mobility had on the quantity of upward communication (Roberts & O’Reilly, 1974). They found that trust and influence both positively related to the quantity of upward communication, and mobility did not really play a factor in the quantity of upward communication. This study was later replicated finding the same results (Blalack, 1986). In essence, people who trust their supervisors and perceive their supervisors as influencing their careers engage in more upward communication.

Communicating Ethically

From a subordinate’s perspective, is upward distortion ever an ethical communicative practice? Often supervisors will want information from a subordinate that could harm the subordinate or her or his coworkers, so determining whether one should distort information or not can be a hard thing to decide. For example, what if your supervisor asks you about one of your coworker’s recent performance and your coworker’s performance was subpar? Do you tell your supervisor the truth knowing that the coworker could be reprimanded or fired, or do you distort the facts in an effort to “save” your coworker? People in organizations often distort information to help themselves or their peers, but is it ever ethical?

On the other hand, what if your supervisor asked you about her or his performance, which has been problematic; do you tell him the truth? Obviously, saying that communication distortion is always unethical would be easy to say, but is that really the case? Can communication distortion be ethical?

The second problem Randy Hirokawa (1979) noted with upward communication relates to filtering. Organizations today often suffer from what they termed info-glut or data smog, which is to say that organizations have a problem with communication overload (Edmunds & Morris, 2000). Just as we discussed earlier in this chapter that downward communication can lead to communication overload, so can receiving too much information from one’s subordinates. Ultimately, there is a fine line between the necessity of ensuring honest upward communication and receiving too much upward communication. Supervisors must learn how to filter out information from all directions that isn’t necessary, but this is a skill that takes time and energy to learn. At the same time, subordinates also need to learn what information is necessary for their supervisors to have and what information is not necessary.

Effective Methods for Upward Communication

While there is no magic bullet for improving upward communication within an organization, we do believe there are four best practices that all supervisors should engage in: establish trust, use multiple mediums, show utility, and decrease barriers. First, and definitely the most important best practice for ensuring quality upward communication, is establishing a trusting relationship with one’s subordinates. As discussed above, trust clearly leads to an increase in upward communication from one’s subordinates.When subordinates trust their supervisors they are more likely to engage in two-way communication that is honest and productive.

Second, Hirokawa recommends that managers utilize multiple strategies when soliciting upward communication. Supervisors should use a variety of strategies for increasing upward communication: routine discussion meetings, supervisor’s appraisals of individual employees, manager’s appraisals of individual supervisors, attitude surveys, employee suggestion programs, grievance procedures, open-door policies, and exit interviews. All of these different strategies can definitely help increase upward communication. However, all of the strategies may not be the most beneficial for all types of information a supervisor needs, so a supervisor should think critically before implementing one strategy over another.

The third best practice for increasing upward communication is to clearly show that subordinate input is taken seriously. Too often people become discouraged when their feedback is given and the feedback is never acknowledged or nothing is done with the feedback. Obviously, not all ideas subordinates have can be legitimately implemented, however we do recommend establishing a method for responding to all ideas. For example, if you have an employee suggestion program, you may also want to implement a response to employee suggestions section in the organization newsletter. When employee suggestions cannot be implemented for legitimate reasons, simply explaining why the suggestions cannot be implemented is the best way to make employees feel that their ideas were taken seriously even if not implemented. Furthermore, when you implement an employee’s suggestion, make sure to communicate to everyone that this has occurred because it will increase the likelihood of future upward communication by all employees.

Lastly, Hirokawa (1979) also recommends decreasing physical barriers between superiors and subordinates in an effort to increase interaction. Based on research in Japanese organizations, Hirokawa (1981) argued that Japanese managers have more effective upward communication with their subordinates because the managers spend more time on the workshop floor directly interacting with their subordinates. The idea of decreasing barriers is nothing new in the United States because Bill Hewlett and David Packard created a management strategy in the 1940s simply titled Management by Walking Around (MBWA). MBWA is an easy way for management to increase interaction with their subordinates and ward off potential organizational problems (Pace, 2008). Too often managers are over taxed with many duties, and overseeing people is just one of many things managers have to accomplish during a workday. However, the only way to really establish a trusting relationship with one’s subordinates is through consistent face-to-face interaction. However, there are three conditions necessary for MBWA.First, managers need to interact with each subordinate and be prepared for honest feedback. During these interactions, managers can learn about potential problems and about what individual subordinates are doing. Second, managers should encourage dialogue about non-work topics. If a manager sticks strictly to work topics, subordinates may perceive her or him as distant and non-communicative. Lastly, managers should not be critical of subordinates while engaging in MBWA. The goal of MBWA is to encourage subordinates to open up and communicate. If a manager is constantly criticizing people during her or his treks out of the office, people will start to dread seeing the manager of the office and will be more likely engage in upward distortion.

Horizontal/Lateral Communication

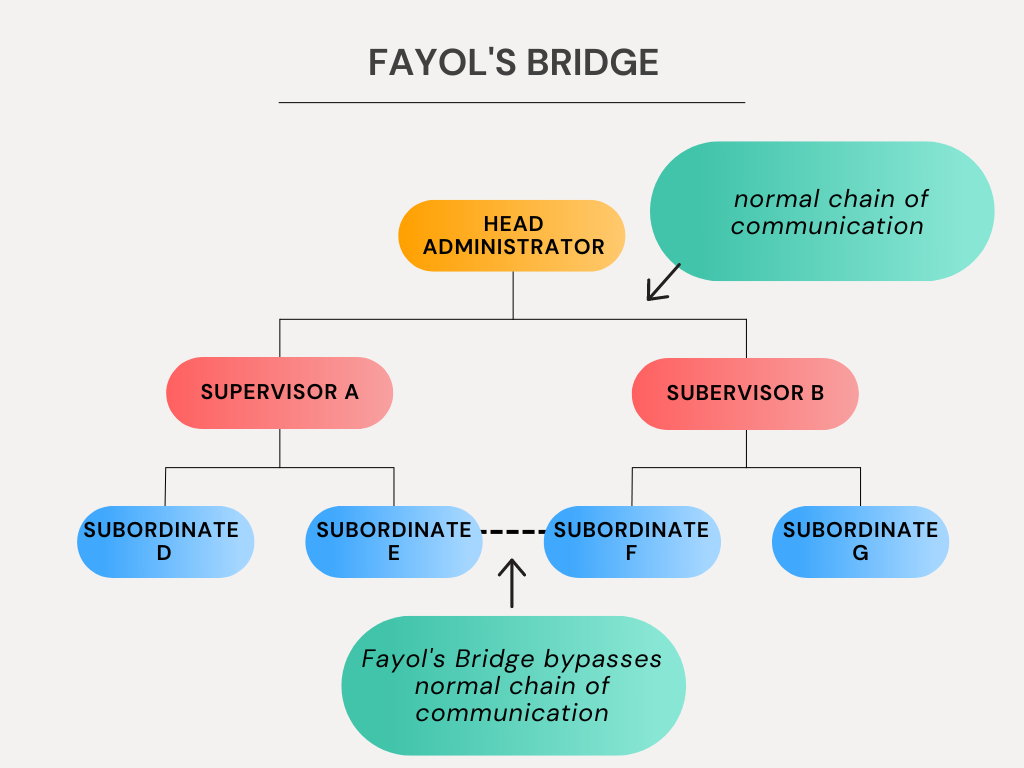

Horizontal or lateral communication consists of messages that are transmitted to other individuals on the same rung of the organizational hierarchy. In essence, horizontal or lateral communication occurs when individuals who have roughly the same status interact with one another in an organization. Occasionally, these lines of communication are firmly established within the organizational hierarchy chart, but typically these lines of communication are not part of the traditional hierarchical chart. As discussed in Chapter 3, one of the earliest theorists on the nature of horizontal/lateral communication was a French mining engineer named Henri Fayol. Fayol published his treatise on administration in 1916 called Administration Industrielle et Générale, but did not reach English readers until 1949 when the text was translated by Constance Storrs as General and Industrial Management. Fayol had lots of ideas on how organizations should function, but his ideas on horizontal communication are what we are interested here. Fayol believed that communication within an organization should travel up and down very clear channels of communication. In Figure 5.1, we see an example of an organizational hierarchy with one head administrator, two supervisors, and six subordinates. Three of the subordinates work directly under Supervisor B and three work directly under Supervisor C. According to Fayol, if subordinate E working under Supervisor B needs to communicate something to subordinate F working under Supervisor C, the message would have to go up the hierarchy and then back down the hierarchy. In this case, Subordinate E, would communicate the message to Supervisor B who would then communicate the message to the head administrator. The head administrator would then communicate the message to Supervisor C, who would finally communicate the message to Subordinate F. However, Fayol did believe that an alternate chain of communication is necessary during periods of crisis. When information needed to get to someone quickly because of a crisis, Fayol created a mechanism that would temporarily bridge two individuals on the same level of the hierarchy.

Figure 5.1 also illustrates how the Fayol Bridge would work. During a crisis, Subordinate E would communicate to Supervisor B the importance of getting the information to Subordinate F quickly. If Supervisor B believes that the speed at which Subordinate F receives the information is important, then Supervisor B will give permission to Subordinate E to transmit that information directly to Subordinate F.

The idea of hierarchical control over messages was very commonplace all the way through the 1950s:

Although communication between departments on the same level occurs, theoretically it is not supposed to be direct. Reports, desires for services, or criticisms that one department has of another are supposed to be sent up the line until they reach an executive who heads the organizations involved. They are then held, revised, or sent directly down the line to the appropriate officials and departments. The reason for this circuitous route is to inform higher officials of things occurring below them. (Miller & Form, 1951, p. 158)

When one reads this quotation from Miller and Form, one is led to believe that vertical (upward & downward) communication is the most common channel of communication in organizations, and it should be. However, the type of organization is the ultimate determinator of whether there is primarily vertical communication or horizontal communication occurring (Simpson, 1959).

By the 1960s and 1970s, researchers began to realize that the idea of primarily vertical oriented communication was highly unrealistic and not necessarily beneficial to organizations. Furthermore, horizontal/lateral communication actually enabled lower level supervisors to engage in automatic horizontal/lateral communication. By automatic, Joseph Massie (1960) was referring to “habitual, routine, and spontaneous reaction of managers to a problem situation” (p. 88). Ultimately, enabling lower level managers to decide courses of action on some decisions relieved high level administrators “not only from making some decisions but also from consciously structuring the decision-making pattern for lower level managers” (Massie, 1960, p. 88). This process of allowing individuals at various levels of the hierarchy to participate in decision-making and implementing courses of action is called decentralization because the decision-making is disbursed through the organization instead of being centered at the top of the hierarchy (Child, 2005; Hilmer & Donaldson, 1996). Furthermore, decentralization of decision-making greatly reduces the problems associated with serial transmission of messages. Earlier in this chapter we discussed how serial transmission of messages leads to all kinds of problems, and the more rungs up and down a hierarchy a message must travel, the greater the chance of the message distortion (Redding, 1972). Now that we have examined the basic perspectives on horizontal/lateral communication, we can examine the types of horizontal/lateral communication, problems with horizontal/lateral communication, and effective methods for horizontal/lateral communication.

Types of Horizontal/Lateral Communication

According to Randy Hirokawa (1979) there are four functions to horizontal communication: task coordination, problem solving, sharing of information, and conflict resolution. The function of horizontal/lateral communication is to help organizational members coordinate tasks to help the system achieve its goals. Often people in different departments are completely unaware of how their department impacts another department’s ability to function. When different departments are brought together and shown how each department helps the organization strive for its goals, departments are able to ascertain how they can actually help each other more effectively.

The second function of horizontal/lateral communication is to allow organizational members to solve problems. The basic process of “brain storming” is always more effective when you have numerous departments thinking about how to solve specific problems. For example, if your entire organization is having problems with recycling, it wouldn’t be beneficial if only members from one department got together to talk about the problem. When there are system-wide problems facing an organization, the organization needs system wide solutions.

The third function of horizontal/lateral communication is the sharing of information among organizational members. As we’ve already mentioned in this chapter, there are numerous reasons why individuals may be reluctant to share information, but when people hoard information the overall organization suffers. The need for sharing can be explained in this way, “it is through the sharing of information that organizational members become aware of the activities of the organization and their collegues [sic]” (Hirokawa, 1979, p. 89).

The final function of horizontal/lateral communication is conflict resolution. When individuals are in conflict with each other, the easiest way to solve the conflict is through direct interaction. Often simple conflicts are a result of misunderstandings that can become exacerbated if not handled quickly and efficiently. For this reason, “in the presence of conflict between organizational members within a department or section, the ability to discuss the matter of concern can often lead to a resolution of the conflict” (Hirokawa, 1979, p. 89). If an organization opts to utilize Fayol’s (1916) ideas of horizontal communication, “one would have to go half-way around the organizational hierarchy to get a message to a collegue [sic] if one were to remove horizontal channels” (Hirokawa, 1979, p. 89). As always, the more direct the path of communication is the more likely the message will remain uncorrupted.

Problems with Horizontal/Lateral Communication

As with both vertical types of communication, horizontal/lateral communication is not without its own share of problems. In fact, Valerie McClelland and Richard Wilmot (1990) reported a study conducted by the consulting group Wilmot Associates in which “more than 60% of employees in a variety of organizations say that lateral communication is ineffective. More specifically, about 45% say communication between peers within departments is inadequate, and 70% claim that communication between departments must improve” (McClelland & Wimot, 1990, p. 32). In fact, the literature has shown us that there are four basic issues that negatively effect on horizontal/lateral communication within an organization: lack of rewards, competition, intra-organizational conflicts, and lack of lateral understanding.

No Reward Structure

The first issue that can negatively affect horizontal/lateral communication within an organization occurs as result of no reward structure for horizontal/lateral communication. Classical theories of organizational communication didn’t even recognize horizontal/lateral communication as an important function yet alone something that should be openly encouraged (Hirokawa, 1979). People who work in organizations are often given numerous tasks, and behaviors that are not rewarded by the organization are simply ignored and seen as nonessential. For this reason, many organizations have a serious lack in both quantity and quality of horizontal/lateral communication.

Inter-Departmental Competition

The second issue that can negatively impact horizontal/lateral communication occurs as a result of inter-departmental competition. Hirokawa (1979) and McClelland & Wilmot (1990) note that many organizations purposefully pit different departments against each other. When departments are forced to compete with each other, there should be no surprise that hoarding information becomes a common phenomenon. Hirokawa (1981) noted that this desire for interdepartmental competition is a uniquely American concept. In his analysis comparing American versus Japanese organizations, this sense of competition often “causes [organizational members] to hoard information, rather than sharing it with their collegues [sic] (Hirokawa, 1981, p. 90). Japanese organizations, on the other hand, foster a sense of collaboration, which actually leads to an increase in both the quality and quantity of horizontal/lateral communication.

Inadequate Lateral Understanding

The final issue that can negatively impact horizontal/lateral communication occurs as a result of inadequate lateral understanding (McClelland & Wilmot, 1990). Lateral understanding is the degree to which individuals within an organization understand the purpose and functions of what individuals do in various departments throughout the organization. Employees often end up wasting very valuable time trying to figure out who does what in an organization when a problem arises. As McClelland and Wilmot (1990) wrote, “employees don’t understand the goals, responsibilities and capabilities of other departments . . . this is evident even at senior levels” p. 33). There are three major outcomes related to inadequate lateral understanding: waste of time, work overlapping, and poor decision making. First, People ultimately waste a lot of time attempting to determine who they should be contacting in the first place. Second, you may end up with two employees in two departments basically performing the exact same task without realizing that someone else is completing the task. Lastly, managers will often make decisions that negatively impact other departments without even knowing this has occurred.

Effective Methods for Horizontal/Lateral Communication

In an attempt to help organizations communicative more effectively, McClelland and Wilmot (1990) devised a series of seven best practices that organizations should adopt to improve horizontal/lateral communication: develop lateral understanding, flexible chain of command, share clear and consistent direction, set the example, institute lateral teams, ensure accountability to departments and organization, make training available, and develop dialogue between shifts and locations.

The first way to improve horizontal/lateral communication is to increase lateral understanding. As previously discussed, when people don’t understand what other parts of the organization are doing, you end up with people wasting time and resources, duplicating work, and/or making decisions that negatively impact other departments. Lateral understanding should become a priority for all individuals within an organization from the very top to the very bottom. In fact, holding “a forum in which to provide supervisors with an understanding of the opportunities, challenges, goals and structures of their area of responsibility” (McClelland & Wilmot, 1990, p. 36). Only when people start learning about the opportunities, challenges, goals, and structures of other departments can they see how to improve horizontal/lateral communication.

McClelland and Wilmot’s (1990) second suggestion for increasing the quality and quantity of horizontal/lateral communication is to establish a flexible chain of command. When organizational members are forced to adhere to rigid lines of communication, the likelihood of productive horizontal/lateral communication is decreased. Only when top administrators realize that Fayol’s scalar chain isn’t effective will they stop feeling the need to micromanage information flow at all levels of the organization.

The third best practice for increasing the quality and quantity of horizontal/lateral communication is to ensure that clear and consistent messages are delivered downward. When all of the supervisors are on the same page, the chance of mixed or conflicting messages getting sent down the hierarchy is greatly reduced. Furthermore, when all subordinates within an organization receive the message simultaneously, supervisors prevent the appearance of senior administration favoring one department over another. Furthermore, systematic downward communication decreases the likelihood of mixed messages, and even though “an inconsistent message is unintentional, it can be destructive to relationships between employees and management” (McClelland & Wimot, 1990, p. 36). Therefore, ensuring effective horizontal/lateral communication among supervisors and coordinating downward messages can help to foster relationships between employees and management.