4.2 Rethinking the Organization

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate among the four approaches to theorizing about organizations: postpositive, interpretive, critical, and postmodern.

- Understand how these approaches are driven by three decisions: about ontology (how things exist), epistemology (how things are known), and axiology (what is worth knowing).

In Chapter 1 we read fifteen representative definitions of “organization” (see Table 1.1). All fifteen contained one or more of the following words (or their variants): system, structure, unit, collective, pattern, coordination.

When we think of a “system” or “structure” we usually think of an object, a thing that exists independently of the people in it. People come and go, but the system endures. Yet when we think of a system as a “thing” we are thinking metaphorically. As noted in the introduction to Chapter 3, a metaphor is not a literal description but rather a linguistic means to grasp a concept by comparing it to something from the real world. Thus, we think of time as an object in such metaphors as “time flies” and “time is money.” In the same way, although a system is not an actual, literal, physical object which you can hold in your hands, thinking of it that way helps you picture how a system functions.

Similarly, when you think of an “organization” you probably think of it as an object with its own existence. Most people do. A corporation, for example, is considered a “person” under United States law for purposes ranging from taxation to free speech. Clearly, however, thinking of an organization as an object is a metaphor. Nevertheless, the way that we conceptualize an “organization” has very real consequences for organizational communication theory.

Three Decisions about Theory

The assumption that an organization is an object with an independent existence—that is to say, it has an “objective” rather than “subjective” reality—is characteristic of the postpositiveAn approach to organizational communication which holds that organizations have objective existences. Since the imperative to optimize performance governs the organization, individual mindsets ultimately are superfluous. Organizational behaviors are therefore best studied in the aggregate through empirical observations that leads to measurable results. (sometimes called positivist or functionalist) tradition in organizational communication scholarship. Below we will review the postpositive perspective and then, as alternatives, introduce the interpretive, critical, and postmodern perspectives on organizations. Each approach to how we conceive of organizations involves different assumptions. For theorists, their assumptions imply three decisions: ontology, epistemology, and axiology.

Ontology

Our ontology is how we think about the nature of being. Do we think of an organization as having its own existence and own behaviors that continue independently of the various managers and employees who come and go over time? Or do we believe these individuals create and continuously re-create the organization and therefore drive its behaviors? Or is our concept of the organization, and our expectations for the form it should take and what it should do, determined by larger historical and cultural forces?

Epistemology

Our epistemology is our philosophy of how things come to be known. Do we believe that knowledge about an organization is attained by observing collective actions and measuring aggregate behaviors? Or by listening to individual members of an organization and interpreting organizational life on their terms? Or by tracing the historical and cultural forces that have shaped people’s expectations for what an organization should be and the roles that managers and employees should play?

Axiology

Our axiology is what we believe is worth knowing, a decision that involves a value judgment. Many social scientists believe that only empirical evidence, or what can be directly and impartially observed and measured, is worth knowing. Others ask whether any research is truly value-neutral or can be based on “just the facts.” Does not the choice of research method influence what is found? Indeed, is not a decision to accept only what can be measured in itself a value judgment? Where some scholars strive to produce impartial knowledge, which organizational management can use to improve results, others believe such a goal implicitly supports the current system and those in power. Furthermore, where some researchers measure aggregate responses, others strive to hear organizational members on their own terms while giving voice to the powerless and thereby effecting social change.

All three issues—ontology, epistemology, and axiology—are deeply implicated in both classical and modern theories of organizational communication.

Four Questions about Organizations

What is now called the postpositive (or sometimes positivist or functionalist) approach dominated organization studies through the 1970s. Most scholars in the field took it for granted that organizations could, and should, be studied through scientific methods. Then in 1979, Gibson Burrell and Gareth Morgan published an influential work that proposed new paradigms for organizational studies. They started with four basic questions about the assumptions of social science:

- Do social realities, such as organizations, have objective or subjective existence; i.e., do they exist on their own or only in people’s minds?

- Can one understand these social realities through observation or must they be directly experienced?

- Is knowledge best gained by scientific methods or by participating in a social reality from the inside?

- Do people have free will or are they determined by their environments?

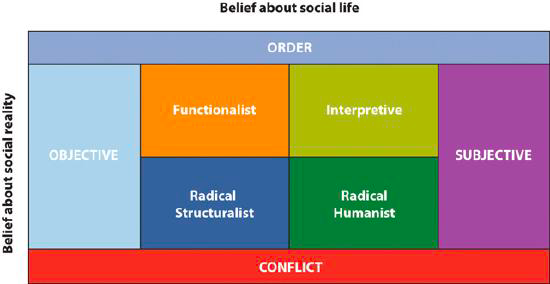

According to Burrell and Morgan, these issues boil down into two fundamental debates: whether social realities exist objectively or subjectively, and whether their basic state is order or conflict (what Burrell and Morgan called “regulation” or “radical change”). These two questions form the axes of a 2 × 2 matrix which we have adapted from Burrell and Morgan and show in Figure below.

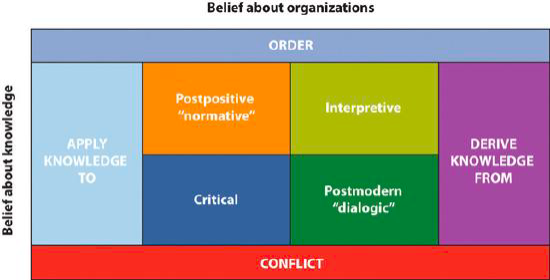

During the 1980s and beyond, scholars used Burrell and Morgan’s matrix to flesh out new approaches for organizational research. For example, see Redding and Thompkins. More recently, Stanley Deetz took stock of how the field has developed since Burrell and Morgan’s original analysis. He proposed a new matrix that retains the order-versus-conflict axis (what Deetz called “consensus” versus “dissensus”) but substituted a new second axis. For Deetz, the two basic questions are: (1) is order or conflict the natural state of an organization; and (2) should researchers apply “knowledge to,” or derive “knowledge from,” an organization—that is, should they start with an existing theory and see how an organization might fit, or study an organization on its own terms? (Deetz called these the “elite/a priori” versus the “local/emergent” approach.) By adapting Deetz’s two questions, we can construct the matrix shown in Figure 4.2.2 below. Though Deetz preferred the terms “normative” and “dialogic” for postpositive and postmodern, we use the latter terms because they are widely recognized among organizational communication scholars.

Thus, postpositive researchers believe that order is the natural state of an organization, and postpositive researchers look to fit a given organization into an existing theory of how order is produced. Interpretive researchers likewise believe that order is the natural state of an organization, but they study each organization on its own terms and how its members establish patterns of conduct. Critical researchers, on the other hand, believe that conflict is the natural state of an organization and bring existing theories about conflicts over power to their analyses of a given organization. Postmodern researchers also believe that conflict is the natural state of an organization, but they look to deconstruct the particular power relations that have emerged in a given organization.

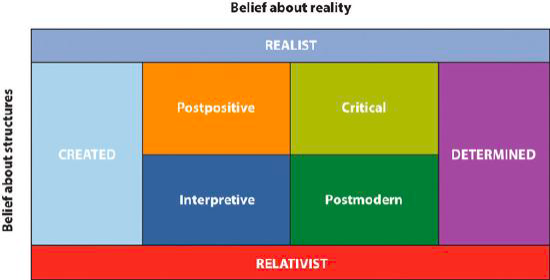

In our view, two questions originally posed by Burrell and Morgan can be recast to provide one more helpful framework for understanding the differences between the postpositive, interpretive, critical, and postmodern approaches. Those questions are: (1) what is the nature of reality; and (2) what is the source of structure? As to the first question, Steven Corman contrasted the realistThe belief that a thing, including a social phenomenon such as an organization, has an existence independent from people’s perception of it. belief “that things (including social phenomena) have a reality that is independent of their being perceived by someone,” with the relativist view that “things (especially social phenomena) exist only in relation to some point of view” (Corman, 2005, p. 25). As to the second question, theorists draw a distinction between structure and agency. As Burrell and Morgan noted, some theorists believe that people are determined by their environments (structures), while others hold that people have free will (agency). Applied to an organization, the question becomes whether its structures are determined by socio-historical processes that operate outside the organization or are created through agency of its members. Again, these two questions about reality and structure can form the axes of the matrix shown in Figure 4.2.3.

Thus, postpositive theorists believe the structures established by an organization’s members literally take on a life of their own, attaining an objective reality that endures independently over time. Critical theorists also believe that organizational structures have a fixed reality, but they see these structures originating in socio-historical processes that operate outside the organization. On the other hand, interpretive theorists believe that an organization has a subjective reality and exists only in relation to the viewpoints of the people inside the organization. Postmodern theorists also believe an organization has a subjective reality, but they see this reality existing in relation to socio-historical points of view that originate outside the organization.

As we will describe at the conclusion of this section, your task is not to choose one “best” approach to organizational communication over another, but to appreciate and draw from each. Toward that end, let us now explore the respective approaches in more detail. In so doing, we will concentrate on their respective ontologies, epistemologies, and axiologies. For the moment, we are only describing the approaches, and not specific theories within each approach.

Postpositive Approach

In the classic disaster-move spoof Airplane!, passengers and crew start to become mysteriously ill. A doctor on board exclaims, “This woman has got to be taken to a hospital.” The chief flight attendant anxiously asks, “A hospital! What is it?” To this the doctor replies, “It’s a big building with patients. But that’s not important right now.” Similarly, we will not spend much time here discussing the difference between positivism and postpositivism. That’s not important right now. Suffice it to say that, as Steven Corman explained, where positivistic scientists of the early twentieth century took the antirealist position that existence only mattered insofar as what meets the eye, today’s postpositivists hold the realist belief that reality exists independently of perception.

Lex Donaldson succinctly captured this perspective by suggesting that “in any situation, to attain the best outcome, the decision makers must choose the structure that best fits that situation . . . with the ideas of the decision-makers making no independent contribution to the explanation of the structure.” In other words, since an organization can survive only if it performs well, managers are ultimately forced to choose the course of action that gets the best results. Even when managers choose lesser options, the resulting performance deficit creates its own pressure to either correct the mistake or go out of business. In the end, “the consciousness of the actors [is] superfluous” because “there will be an irresistible tendency for organization managers to choose options that conform to the situational imperative . . . with no moderation by managerial ideas”(Donaldson, 2003, pp. 44-45). The same holds true when managers communicate; they are forced, in the end, to choose messages and channels that best contribute to the bottom line. In the postpositive view, then, the purpose of organizational communication is instrumental—that is, an instrument for achieving results. Accurate messages and precise instructions are therefore seen as the best guarantors of optimal performance.

Given this conception of the organization, we can see how postpositivism fits together with its own distinctive ontology (its belief in how things exist), epistemology (its belief in how things are known), and axiology (its belief in what is worth knowing). Because the organization has an independent reality, its imperatives—to survive, to get the best results—drive what people do (rather than vice versa). And because individual mindsets ultimately do not matter, then researchers learn about an organization by observing its aggregate behaviors.

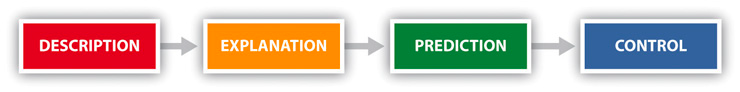

Thus, for example, Frederick Taylor’s classical theory of scientific management is based on the assumption that what comes out of the organization is a function of went in. This idea is expressed in popular acronym GIGO for “garbage in, garbage out.” The task for managers who observe poor output is to scientifically adjust input. If so, their metaphorical well-oiled machine can work at maximum capacity. The goal, not only for managers but for postpositive organizational theorists, is to move from description and explanation to prediction of causes and effects—which implies the ability to control effects by adjusting causes. Figure 4.2.4 below illustrates this progression. In organizational research, studies undertaken from a postpositive perspective are often intended to generate knowledge that can be applied to improving management practices.

Even as Frederick Taylor did a century ago with his time and motion studies, those today who study organizations from a postpositive perspective see themselves as social scientists. They practice nomothetic research methods that emphasize scientific testing of hypotheses and employ quantitative methods, such as surveys and experiments, which generate numerical data. For postpositive researchers, this is the only data worth knowing; they disfavor the ideographic data generated by such qualitative methods as ethnographic fieldwork, interviews, journals, and diaries because postpositivists find these methods inherently subjective and unable to describe what they perceive as the objective reality of organizational communication. The ultimate goal of nomothetic research is to discover general laws that are applicable across different cases. Classical examples of the nomothetic approach to research are described in Chapter 3, including the Hawthorne Studies of Elton Mayo and the pajama factory study of Kurt Lewin.

As an interesting caveat to this discussion, people who conduct what we are labeling “postpositive” research generally do not describe their work as such. Because the field of organizational communication research grew out of the social-psychological and business research of the first part of the 20 century, today’s postpostive researchers follow their counterparts in fields like industrial psychology or organizational behavior and categorize themselves as social scientists. While social-scientific researchers in organizational communication do not discount what other researchers in the larger field of organizational communication are doing, they do see themselves and their research as very distinct from the work of interpretive, critical, and postmodern researchers. As Patric Spence and Colin Baker noted in their article examining the types of organizational communication research published within the field, postpositive research still accounts for almost half of the research published today.

| Ontology (how things exist) | Epistemology (how things are known) | Axiology (values for research) | Purpose of Org. Communication |

| Realism | Observation | Intervention | Instrumental |

| Organizations have an objective existence that is independent of the people in them. People come and go but the organization endures. | Since people ultimately must choose actions that get the best organizational results, individual mindsets do not matter. Thus, to learn about an organization it is sufficient to observe its aggregate behaviors. | Social-scientific research generates knowledge that can be used to make predictive theories and applied to management practices. | Organizational imperatives that force people to choose the most effective actions apply to communication actions. Thus, accurate and precise communications are most effective. |

Interpretive Approach

Where postpositive theorists believe the organization drives what its people do, interpretive theorists believe the reverse: that people drive what their organizations do—and, in fact, what their organizations are. As Dennis Mumby and Robin Clair (1997) put it, “organizations exist only in so far as their members create them through discourse,” with discourse being “the principal means by which organization members create a coherent social reality that frames their sense of who they are” (p. 181). In other words, communication is not just one activity, among many others, that an organization “does.” Rather, the organization itself is constituted through its members’ communication; it does not exist objectively, but only in relation to its members’ points of view.

This explains the ontology of interpretive theorists, their belief in how organizations have being. Their epistemology, or how these theorists believe knowledge is gained, is expressed by the word “interpretive.” Recall that postpositive theorists believe the mindsets of individuals do not matter since they are irresistibly forced choose the most effective courses of action; thus, to know an organization it is sufficient to observe its aggregate behaviors. By contrast, interpretive theorists believe that simple observation is insufficient; the mindsets of organization members must also be interpreted. Hence, this approach to studying organizational communication is called interpretivism. (Some theorists also use the term “social constructionism” to emphasize how social phenomena, such as organizations, are constructed through social interaction.)

But how do you interpret what is going on inside someone’s mind? Many methods are used. These usually begin by collecting primary data—interviews with people at various levels of the organization, and copies of organizational documents such as mission statements, annual reports, policy manuals, internal memoranda, and the like. Researchers who engage in organizational ethnography do fieldwork in which they may spend a year or more visiting an organization, attending weekly staff meetings, participating in rituals such as office parties and company picnics, joining in ordinary conversations around the water cooler, and then recording their observations. Techniques for analyzing these ideographic data are also varied and include discourse analysis, conversation analysis, genre analysis, rhetorical analysis, and other methods.

These analytical methods involve an examination of how organization members use language to construct a shared social reality. By interpreting how language is used (e.g., company slang, recurring phrases, common metaphors, use of active and passive voice, what arguments employees find persuasive, how people address one another, how people take turns in talking) researchers uncover the underlying assumptions within an organization that its people take for granted and may not explicitly verbalize. Interpretive researchers, then, believe that organizational communication is not merely an instrument for getting results. Rather, people in organizations communicate with each other to make sense of their workplace and negotiate their places within the organization. Though managers may believe that precise instructions maximize productivity, directives that ignore employee perceptions can be disregarded, misinterpreted, and even counterproductive.

The axiology of interpretive scholars is evident from their research. Where postpositive researchers do not regard organization members’ individual mindsets (which cannot be directly observed or measured) as worth knowing, interpretive researchers believe these data and their interpretation are essential to understanding organizational life. Moreover, where the goal of postpositive researchers is to move from description and explanation to prediction of organizational behaviors, interpretive scholars believe that studying an organization on its own terms means producing a description and interpretation of organizational life that is faithful to its members’ own understandings. Interpretive researchers can, and do, make their findings about an organization’s communication and culture available to their subjects; in turn, organizations may use this information to address negative perceptions and to change a dysfunctional company culture into a more humane one. Interpretive researchers see their role not as changing the status quo but describing it. Yet identifying the unspoken assumptions that circulate within an organization may be the first step in addressing inhumane practices.

| Ontology (how things exist) | Epistemology (how things are known) | Axiology (values for research) | Purpose of Org. Communication |

| Relativism | Interpretation | Description | Negotiation |

| Organizations come into existence and are then maintained through their members’ communication.Thus, organizations exist in relation to its members’ points of view. | To learn about an organization, simple observation of aggregate behaviors is insufficient. The mindsets of members must also be interpreted. | Research aims to describe the organization on its members’ own terms, although knowledge can be used to develop general theories and applied to management practices. | People in an organization use communication to make sense of the work environment, establish shared patterns, negotiate their own identities, and enact their roles. |

Critical Approach

A generation ago you might have read a company manual that stated, “When an employee is late to work, he must report immediately to his supervisor.” Today we read that sentence and, right away, notice its use of sexist language. But at the time, it was common to use the masculine pronoun as an inclusive reference for both genders. For decades, even centuries, the practice was so widely accepted as natural and self-evident that people did not question this use of the masculine pronoun. In the 1960s, for example, the mission of the starship Enterprise in the Star Trek television series was “to boldly go where no man has gone before.” Not until a sequel series debuted in the late 1980s was the mission statement rephrased, “To boldly go where no one has gone before.” Living in the twenty-first century, we now wonder how an earlier generation could have accepted sexist language without question. Yet consider: Which of our own assumptions will someday seem “unenlightened” to our children and grandchildren?

Think of some things we take for granted about the workplace. If someone asked you who “owns” the company you work for, you would answer with the name of person who is the “owner” in a financial sense. It just seems natural and self-evident that the one who holds the purse strings is the owner—even though you too have a tangible stake in the company and help make its activities possible. And in a free enterprise economy, we take for granted the notion that increased profits benefit everyone. Even college students, before they enter the workforce, accept this premise. Most young people attend college to “make more money” by learning job skills which will fit them into the needs of moneymaking corporations. Therefore, as corporations and their employees all make more money, everyone wins.

These assumptions illustrate what critical theorists call the reification and universalization of managerial interests. Reification is the process by which something historical is made to seem natural. For example, what we call the profit motive did not always exist; it emerged under specific historical conditions as premodern feudal economies gave way to modern capitalist economies. But we have so reified the profit motive that its pursuit seems natural, normal, self-evident, and beyond questioning. This process of reification produces a “double move” by ensuring that managerial interests are considered the only legitimate interests, while simultaneously hiding the domination of those interests by making them seem perfectly natural. Thus, the interests of management are universalized and represented as identical to everyone’s interests. To speak of “company interests” is, in reality, to speak of managerial interests. Such distortion becomes, from a critical perspective, the very purpose of organizational communication—that is, the operation of dominant interests to create a “false” consensus between management and employees.

Critical theorists, like the postmodern theorists we will review below, see the organization as a created by larger forces of history and society. But unlike postmodern theorists who see the organization in constant flux within the swirling streams of those forces, critical theorists tend to see the structures of power and domination as being so reified that they constitute “a concrete, relatively fixed entity” (Deetz, 2001 , p. 27). Again, this requires a decision about ontology or the nature of existence—in our case, about the nature of organizational existence.

In addition to reification and universalization, critical theorists are concerned with two more questions: how reasoning in organizations becomes grounded in “what works,” and how dominant managerial interests gain the consent of subordinate interests. Jurgen Habermas noted how the modern age has increasingly supplanted practical reasoning that seeks mutual consensus, with technical reasoning that calculates the means and controls needed to accomplish a desired end. Critical theorists have applied this insight to organizational life by critiquing how corporations make technical reasoning, or determination of “what works” in achieving managerial interests, appear to be the only rational approach. Practical reasoning that fosters mutual determination of organizational goals either is made to seem irrational or is even leveraged by management as another “technique” to further its own interests. Thus, ideas such as promoting worker participation are either dismissed as inefficient or used as a new means to bring workers into alignment with corporate interests. Why do workers consent to such domination? Critical theorists have looked at bureaucratic forms, at coercions and rewards, and at organizational cultures that provide no chance for alternative modes of thinking—or that cause employees to identify so completely with an organization, they internalize its goals into their sense of personal duty and job satisfaction. Such employees need not be controlled; they discipline themselves.

If, according to critical theorists’ ontology, organizational structures have been reified into an objective existence, then according to their epistemology, how do these taken-for-granted structures become known? Most critical organization researchers engage in ideology critique. These researchers bring to their subjects an existing theory and then use it as a framework to expose how a dominant ideology has operated to reify and universalize its interests. A good example is provided by Karl Marx, the originator of ideology critique. He theorized that differences between capital and labor are built into the very structure of the capitalist system and its ideology. Then he employed his theory to explain how the few (who owned capital) could not only exploit the many (who owned only their labor), but could also make their domination appear legitimate and natural. Notions of economic class differences remain an influential strand of ideology critique. Yet other bases for criticism have also become important. More recently, feminist theory offers another example of ideology critique as researchers bring theories about gender-based structures of domination and use these as frameworks to expose or “denaturalize” the patriarchal assumptions that organizations take for granted.

In addition to ideology critique, a second stream of critical scholarship has emerged that follows the theories of Jurgen Habermas about communicative action. The theory of communicative action: Vol. 2, Lifeworld and system. Boston: Beacon. Where critical scholars have traditionally plumbed the ways that meaning, thought and consciousness itself are distorted by dominant discourses, Habermas began in the late 1970s to explore how communication is distorted. He proposed that, ideally, a communicative act should satisfy four conditions: participants should have equal opportunities to speak, should be heard without preconceptions of what is “true” and “proper,” and should be able to speak according to their own lived experiences. Scholars, then, can critique how organizations distort these conditions. Thus, managers have more opportunities to speak; “bottom line” considerations are a privileged form of knowledge and seen as the only rational basis for resolving issues; the organization’s structure dictates, in advance, the proper relations between management and labor; and discussions of workplace concerns must take place within the context of “company” (i.e., managerial) interests. Yet Habermas’s model for communicative action also suggests possibilities for a positive agenda. A number of scholars have proposed how legitimate organizational communication can be restored through democratization of the workplace (Cheney, 1995; Deetz, 1992; Harrison, 1994).

As we learned above, postpositive and interpretive theorists look for order to emerge in organizations. Postpositive researchers look for the ways that organizational imperatives for efficiency and productivity brings members into alignment; interpretive researchers look for the ways that members create, through their communication, stable communities and shared cultures. By contrast, critical theorists believe that organizations are sites where historical and societal ideologies are in conflict, and where reified structures produce dominant and subordinate discourses. Other researchers may look for surface stability, but critical theorists’ axiology regards an organization’s submerged voices—workers, women, people of color—as worth knowing. Critical theorists’ scholarship aims to recover these marginalized voices, lay bare an organization’s reified structures for all to see, reopen possibilities previously foreclosed by those structures, and replace false consensus with true consensus. Given that emancipation is their goal, critical researchers combine scholarship with activism. These qualities—the ontology, epistemology, and axiology of the critical approach to organizations—are summarized in Table 4.2.3 below.

| Ontology (how things exist) | Epistemology (how things are known) | Axiology (values for research) | Purpose of Org. Communication |

| Realism | Critique | Emancipation | Distortion |

| The power structures of organizations have an objective existence formed by external historical and cultural forces and that is independent of the people in them. | Exposing the hidden power structures in organizations is accomplished by using general theories about oppression as a framework to analyze a particular organization. | Research aims to expose the hidden power structures in organizations so that marginalized interests can resist and previously foreclosed opportunities become possible. | Communication by the dominant interests in organizations systemically distorts meaning, thoughts, consciousness, and communicative actions so that domination seems natural and alternative expressions are foreclosed. |

Postmodern Approach

Many critical theorists hold that historical and cultural forces produce power structures with fixed existences, but postmodern theorists of organizational communication take a different view. “Reality” constantly fluctuates in the ongoing contests among competing historical and cultural discourses. Humans themselves are sites of competition between these discourses so that—despite our conceit that we have autonomous identities and control our own intentions—we are products of the multiple voices which shape and condition us. As Robert Cooper and Gibson Burrell (1988) explained, postmodern theorists “analyze social life in terms of paradox and indeterminacy, thus rejecting the human agent as the center of rational control and understanding.” In contrast to the modernist approach in which the “organization is viewed as a social tool and an extension of human rationality,” the postmodern approach sees the “organization [as] less the expression of planned thought and calculative action and more a defensive reaction to forces extrinsic to the social body which constantly threaten the stability of organized life” (p. 91). Perhaps an analogy can help. Imagine the sweep of great historical and cultural discourses as an ocean. Its constantly swirling waves and currents determine the actions and perceptions of all who sail upon it. An organization, then, is like a flotilla of ships that negotiate a temporary agreement to sail as a convoy until land is reached. Though an organization may last for decades, rather than days or weeks, in time the currents of history and society that brought it together will pull it apart. Postmodern theorists therefore reject the notion that, as a social object, the “organization” has an objective and enduring existence.

As postmodern theories of organizational communication have developed over the past generation, several themes have emerged. First is the centrality of discourse, so that an organization is regarded as a “text” that postmodern analysts can “read.” The goal in “reading” this “text” is to unravel the underlying—and hidden—historical and cultural discourses which are reflected in the organization. This focus on discourse also means that postmodern scholars view language, rather than thought or consciousness, as the decisive factor in the social construction of organizations. Individuals are not the bearers of meaning, but are caught in webs of meaning that language creates. Following on this idea, a second theme emerges. Organizations are said to be de-centered; the free will of its members are not the central driving force since people are preconditioned by language. Moreover, since organizations are only clusters of temporary consensus between competing discourses, then over time theses discourses tend to produce fragility rather than unity. Different levels of organization—from executives and middle managers to office employees and field personnel—look at things according to their own experiences and interests. Their multiple voices generate varying perspectives, producing multiple social realities rather than a single organizational culture. Thus, postmodern scholars say that organizations are fragmented. Nor is clash of voices without effect on individuals, who are shaped by the multiple discourses operating throughout the organization and surrounding society. For this reason, postmodernists say that individuals’ organizational identities are overdetermined and therefore precarious and unstable.

Given that each organization is a unique “text” that is ever fluid, a third theme in postmodern analysis is what Jean-Francois Lyotard (1984) called an “incredulity toward metanarratives” (p. xxiv). In contrast to critical scholars who look at organizations through the prism of an overarching theory—such as Marx’s theories about class struggle or Habermas’s theories about communicative action—postmodern scholars deconstruct the “text” of an organization for what it is, without fitting it into an a priori theoretical framework or metanarrative. Thus, a fourth theme in the postmodern approach to organizations is the need to deconstruct the particular connections, within each organization, between knowledge and power. What we call organizational communication is, for postmodernists, the ongoing contest between discourses. The dominant interest works to sustain its power by ensuring that organizational knowledge is rendered on its own terms and other interpretations seem unnatural. Postmodern scholars strive to reopen taken-for-granted discourses of knowledge and power, trace their formation, and help recover the voices which have been marginalized.

In tracing out the knowledge/power connection, many postmodern organizational scholars follow the work of French philosopher Michel Foucault. Like Foucault, these scholars are concerned with the ways that modern organizations have eliminated the need to enforce discipline through physical punishment and real-time surveillance, but have “manufactured consent” and thereby “produced” employees who willingly discipline themselves. Nevertheless, Foucault did not see power as all bad. He held that power relations, being “rooted deep in the social nexus,” are inescapable; they arise from the fact of society itself and are therefore not “a supplementary structure whose radical effacement one could perhaps dream of.” The goal is not to abolish power and somehow create a perfectly free society, for a “society without power relations can only be an abstraction.” Rather, the goal is a more nuanced understanding that makes possible “the analysis of power relations in a given society, their historical formation, the source of their strength or fragility, the conditions which are necessary to transform some or to abolish others” (Foucault, 1982, p. 791). Toward that end, power may be seen not only as constraint; it also enables action by marking out ranges of possibilities and channels for their realization. Postmodern scholarship lays bare the power relations within organizations, putting these relations back into play and helping marginalized voices restructure the field of action to open up previously foreclosed possibilities. For postmodernists, then, the three decisions that organizational theorists must make—about ontology (how things exist), epistemology (how things are known), and axiology (what is worth knowing)—are summarized in Table 4.2.4 below.

| Ontology (how things exist) | Epistemology (how things are known) | Axiology (values for research) | Purpose of Org. Communication |

| Relativism | Deconstruction | Denaturalization | Contestation |

| Organizations come into existence as temporary combinations of interests against the threatening fluidity of larger historical and cultural discourses, so that they exist only in relation to those external forces. | Organizations are “texts” that can be “read.” The goal is to deconstruct, or trace back, the historical and cultural discourses that led to the formation of a particular organization’s power relations. | In the ongoing contest between organizational discourses, dominant interests maintain power by ensuring organizational knowledge is rendered on its own terms and made to seem natural.Research aims to “denaturalize”and thus reopen hidden power relations. | Organizational communication is a means by which the discourses of an organization’s various interests are contested. In this contest, some discourses dominate and others are marginalized. |

Combining Approaches

Until the 1970s, organizational research mostly proceeded from what is now called a postpositive approach. Articulating new paradigms, Stanley Deetz (2001) noted, “gave legitimacy to fundamentally different research programs and enabled the development of different criteria for the evaluation of research” (p. 8). At the same time, however, labeling has created distinctive communities of researchers that each favor a particular paradigm and can sometimes ignore or even dismiss the work of others

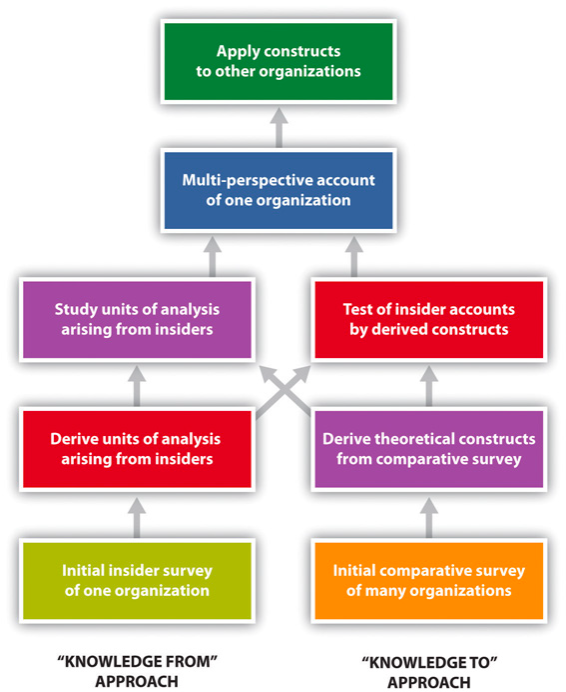

The authors of this textbook individually take different approaches to organizational communication research. Yet we believe all perspectives make valuable contributions. For example, we share a common interest in communication by members of organized religions. Jason Wrench and Narissra Punyanunt-Carter have conducted, with other colleagues, extensive surveys of religious believers to produce an aggregate statistical picture of their communication behaviors. By contrast, Mark Ward spent several years visiting the local churches of a religious sect, participating in their worship and rituals, observing their communication firsthand, and learning how they talk among themselves. To use Deetz’s distinction cited above, Ward derives “knowledge from” insiders on their own terms, while Wrench and Punyanunt-Carter consult existing theories and apply that “knowledge to” observed behaviors. Yet we see these different approaches not as an “either/or” choice but as complementary. “Insider” research contributes detailed cases of organizational communication that, taken together with cases of other organizations, may help construct more robust general theories. On the other hand, theoretically-informed research may identify broad patterns in organizational communication that can help those doing “insider” research make sense out of hundreds of separately collected observations. Figure 4.5 below provides a graphic representation of this dynamic.

Key Takeaways

- Different conceptions of an “organization” are behind different approaches to theorizing about organizational communication. The postpositive approach holds that an organization has an objective existence; people come and go, but the organization endures. The interpretive approach holds that an organization has a subjective existence; people create and sustain it through their communication. The critical approach holds that the structures of power within an organization have a fixed existence and reflect larger historical and cultural forces. The postmodern approach also holds that the power relations within an organization reflect larger historical and cultural discourses, but that these discourses are fluid and ever changing.

- Theories of organizational communication reflect assumptions with regard to ontology (how things, including social phenomena such as organizations, have existence), epistemology (how things become known), and axiology (what is worth knowing). In the previous takeaway, the ontologies of the four approaches to theorizing about organizational communication are described. The postpositive approach holds that organizations are known through scientific inquiry and that only empirical findings are worth knowing. The interpretive approach holds that organizations are known by directly experiencing them and that individuals’ perceptions (though these cannot be measured) are worth knowing. The critical approach holds that hidden power structures are exposed by applying general theories about domination and that the voices of marginalized groups are worth knowing. The postmodern approach also holds that marginalized discourses are worth knowing, but that hidden power relations are exposed by deconstructing, or tracing back, how various discourses have formed in a given organization.

Exercises

- Think of the college or university that you are attending. Then imagine a prospective student asking you, “What is the best way to find out what your school is really like?” Would you advise the prospect to take a survey of current students, or to spend some time living on campus and participating in school activities? What is the reason for your advice? Could you imagine how a combination of both methods could be useful? Explain yourself.

- We described above how most students go to college to “make more money,” taking for granted that higher education is about fitting into the needs of corporations. Can you think of other ways that the corporate world has influenced college students so that you might think in ways that serve corporate interests? Why might these thoughts seem natural to you, so that you do not question them?

- Which approach to theorizing organizational communication—postpositive, interpretive, critical, or postmodern—makes the most sense to you? Why? Explain your answer.

References:

Burrell, G., & Morgan, G. (1979). Sociological paradigms and organizational analysis. London: Heinemann.

Cheney, G. (1995). Democracy in the workplace: Theory and practice from the perspective of communication. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 23, 167-200

Cooper, R., & Burrell, G. (1988). Modernism, postmodernism, and organizational analysis: An introduction. Organization Studies, 9, 91-112; pg. 91.

Corman, S. R. (2005). Postpositivism. In S. May & D. K. Mumby (Eds.), Engaging organizational communication theory and research: Multiple perspectives (pp. 15-34). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Davison, J., Koch, H. W. (Producers), & Abrahams, J. Zucker, D. & Zucker, J. (Directors). (1980). Airplane! [Motion picture]. United States: Paramount.

Deetz, S. (1992). Democracy in the age of corporate colonization: Developments in communication and the politics of everyday life. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Deetz, S. (1994). Representative practices and the political analysis of corporations. In B. Kovacic (Ed.), Organizational communication: New perspectives (pp. 209-242). Albany: State University of New York Press.

Deetz, S. (2001). Conceptual foundations. In F. M. Jablinb & L. L. Putnam (Eds.), The new handbook of organizational communication: Advances in theory, research, and methods (pp. 3-46). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Donaldson, L. (2003). Organization theory as a positive science. In H. Tsoukas & C. Knudsen, The Oxford handbook of organizational theory: Meta-theoretical perspectives (pp. 39-62). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison (A. Sheridan, Trans.). New York: Pantheon.

Foucault, M. (1980). The history of sexuality (R. Hurley, Trans.). New York: Pantheon.

Foucault, M. (1982). The subject and power. Critical Inquiry, 8, 777-795; pg. 791.

Foucault, M. (1988). Technologies of the self. In L. H. Martin, H. Gutman & P. H. Hutton (Eds.), Technologies of the self: A seminar with Michel Foucault (pp. 16-49). Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Habermas, J. (1971). Knowledge and human interests (J. Shapiro, Trans.). Boston: Beacon.

Habermas, J. (1984). The theory of communicative action: Vol 1., Reason and the rationalization of society (T. McCarthy, Trans.). Boston: Beacon.

Harrison, T. (1994). Communication and interdependence in democratic organizations. In S. Deetz (Ed.), Communication Yearbook 17 (pp. 247-274). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lyotard, J.-F. (1984). The postmodern condition: A report on knowledge (G. Bennington & B. Massumi, Trans.). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; pg. xxiv.

Mumby, D. K., & Clair, R. P. (1997). Organizational discourse. In T. A. van Dijk (Ed.), Discourse as structure and process, Vol. 2 (pp. 181-205). London: Sage; pg. 181.

Punyanunt-Carter, N. M., Wrench, J. S., Corrigan, M. W., & McCroskey, J. C. (2008). An examination of reliability and validity of the Religious Communication Apprehension Scale. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 37, 1-15.

Punyanunt-Carter, N. M., Corrigan, M.W., Wrench, J. S., & McCroskey, J. C. (2010). A quantitative analysis of political affiliation, religiosity, and religious-based communication. Journal of Communication and Religion, 33, 1-32.

Redding, C., & Tompkins, P. (1988). Organizational communication—Past and future tenses. In G. Goldhaber & G. Barnett (Eds.), Handbook of organizational communication (pp. 5-34). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Redding & Tompkins, op. cit.; Putnam, L. (1982). Paradigms for organizational communication research. Western Journal of Speech Communication, 46, 192-206.

Spence, P. R., & Baker, C. R. (2007). State of the method: An examination of level of analysis, methodology, representation and setting in current organizational communication research. Journal of the Northwest Communication Association, 36, 111–124.

Ward, M., Sr. (2009). Fundamentalist differences: Using ethnography of rhetoric (EOR) to analyze a community of practice. Intercultural Communication Studies, 18, 1-20.

Ward, M., Sr. (2010). “I was saved at an early age”: An ethnography of fundamentalist speech and cultural performance. Journal of Communication and Religion, 33, 108-144.

Ward, M., Sr. (2011). God’s voice in organizational communication: A root-metaphor analysis of fundamentalist Christian organizing. Paper presented at National Communication Association 97th Annual Convention, New Orleans, LA, November 2011.

Ward, M., Sr. (in press). Managing the anxiety and uncertainty of religious otherness: Interfaith dialogue as a problem of intercultural communication. In D. S. Brown (Ed.), Interfaith dialogue: Listening to communication theory. Lanham, MD: Lexington.

Wrench, J. S., Corrigan, M. W., McCroskey, J. C., & Punyanunt-Carter, N. M. (2006). Religious fundamentalism and intercultural communication: The relationship among ethnocentrism, intercultural communication apprehension, religious fundamentalism, homonegativity, and tolerance for religious disagreements. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 35, 23-44.

An approach to organizational communication which holds that organizations have subjective existences and, in fact, are constituted through their members’ communication. As such, it is not enough to observe aggregate behaviors; individual mindsets must be also be interpreted.

An approach to organizational communication that employs theory as a framework to expose the hidden power structures in organizations and the ways that dominant interests distort meaning, thought, consciousness, and communicative action to maintain their domination by marginalizing alternative expressions.

An approach to organizational communication which holds that organizations come into existence as temporary combinations of interests against the threatening fluidity of larger historical and cultural discourses. As a reflection of these discourses, the organization is a “text” that can be “read” in order to trace back how its hidden power relations were formed.

Philosophy of how things have being. Some theorists believe an organization exists independently from how people perceive it; others believe an organization exists only in relation to the perceptions of its people or in relation to society.

Philosophy of how things are known. Some researchers believe it is sufficient to observe and measure an organization’s aggregate behaviors; others believe that the mindsets and interactions of individuals must also be interpreted.Philosophy of how things are known. Some researchers believe it is sufficient to observe and measure an organization’s aggregate behaviors; others believe that the mindsets and interactions of individuals must also be interpreted.

Philosophy of what is worth knowing. Some researchers only accept knowledge gained empirically through observation and measurement of aggregate behaviors; others believe that people’s perceptions must be analyzed.

The belief that a thing, including a social phenomenon such as an organization, has an existence only in relation to some point of view.

The debate among theorists about whether people are determined by their environments (structure) or have free will (agency).

An approach to knowledge that emphasizes scientific testing of hypotheses and employs quantitative tests, such as surveys, which generate numerical data. The ultimate goal of nomothetic research is to discover laws that can be generally applied across many cases.

An approach to knowledge that takes each case on its own terms by considering qualitative data such as ethnographic fieldwork, interviews, journals, and diaries.

The word literally means “writing the culture.” Organizational ethnographers conduct fieldwork, perhaps spending a year or more to directly experience an organization through participation and observation. The goal is to describe the organizational culture in terms that are faithful its members’ understandings.

According to critical theory, the process by which dominant interests are represented as identical to everyone’s interests. Thus, to speak of “company interests” is, in reality, to speak of managerial interests.

According to critical theory, the process by which something historical is made to seem natural. Thus, the dominant interests within an organization appear to be natural and self-evident.

Reasoning that, according to critical theory, calculates the means and controls needed to accomplish a desired end. In organizations, technical reasoning is made to seem that only rational basis for decisions. For the modern age it has largely replaced practical reasoning which seeks mutual consensus.

An approach to critical scholarship that employs theory to expose how dominant interests distort meaning, thought, and consciousness to simultaneously legitimize and hide their domination.

An approach to critical scholarship that examines how dominant interests distort communication processes to sustain their domination by foreclosing alternate expressions. But legitimate communication may be restored, it is argued, through greater democratization of the workplace.

Because postmodernists believe that language is the decisive factor in constructing societies, organizations and individuals, then discourse is the central focus of their studies.

Because postmodernists believe that individuals are not autonomous but are shaped by language, they hold that individual free will is not the central driving force of an organization.

Because postmodernists believe that organizations are temporary and fluid combinations of differing interests, they hold that the various discourses of the interests do not produce the stability of a single unified pattern but instead generate multiple social realities that lead to organizational fragility and fragmentation.

Because postmodernists believe that individuals are not autonomous but are sites where multiple discourses are simultaneously in conflict, then identities of people within organizations are always fluid and partial—and thus overdetermined—rather than stable and continuous.

Postmodernists regard with incredulity that suggestion that a single “great story,” such as an overarching general theory, can provide all the answers.

Postmodernists believe that an organization is a “text” that can be “read.” Deconstruction is the method by which analysts trace back the discourses that have formed the power relations within an organization.