Using Computer-Aided Argument Mapping to Teach Reasoning — Studies in Critical Thinking

10

Using Computer-Aided Argument Mapping to Teach Reasoning

Martin Davies, Ashley Barnett, and Tim van Gelder

Introduction

[1], [2]

Argument mapping is a way of diagram

m

ing the l

ogical structure of an argument

to explicitly and concisely represent reasoning.

(See F

igure 1, for a

n

example.)

The use of argument mapping

in critical thinking instruction has increased

dramatically

in recent decades. A brief history of argument mapping is provided at the end of this p

a

per.

P

re- and post-test

studies

have

demonstrate

d t

he pedagogi

cal ben

e

fit of argument mapping

using cohorts of university students and i

n

telligence analysts

as subjects,

and

by

comparing

argument map

ping

intervention

s

with

data from

comparison groups or benchmarks from other meta-analytic reviews

. It

has been found that

intensive practice mapping argume

n

ts with the aid of software has

a strong positive e

f

fect on the critical thinking ability of students

. Meta-analys

i

s

has

shown that high-intensity argument mapping courses improve critical thinking scores by

around 0.8

of a standard

deviation

—

more than twice the

typical effect

size

for

standard

c

ritical thinking courses

(van Gelder, 2015)

.

This strongly suggests that argument mapping is a very effective way to teach critical thinking.

The process of making an argument map is beneficial because it encourages students to construct (or reconstruct) their arguments with a level of clarity and rigor that, when divorced from prose, often goes

unnoticed. The shortcomings of a

badly-constructed

map are plain to see. This is not the case with dense blocks of written prose, which can give an impressionisti

c sense of rigor to the reader.

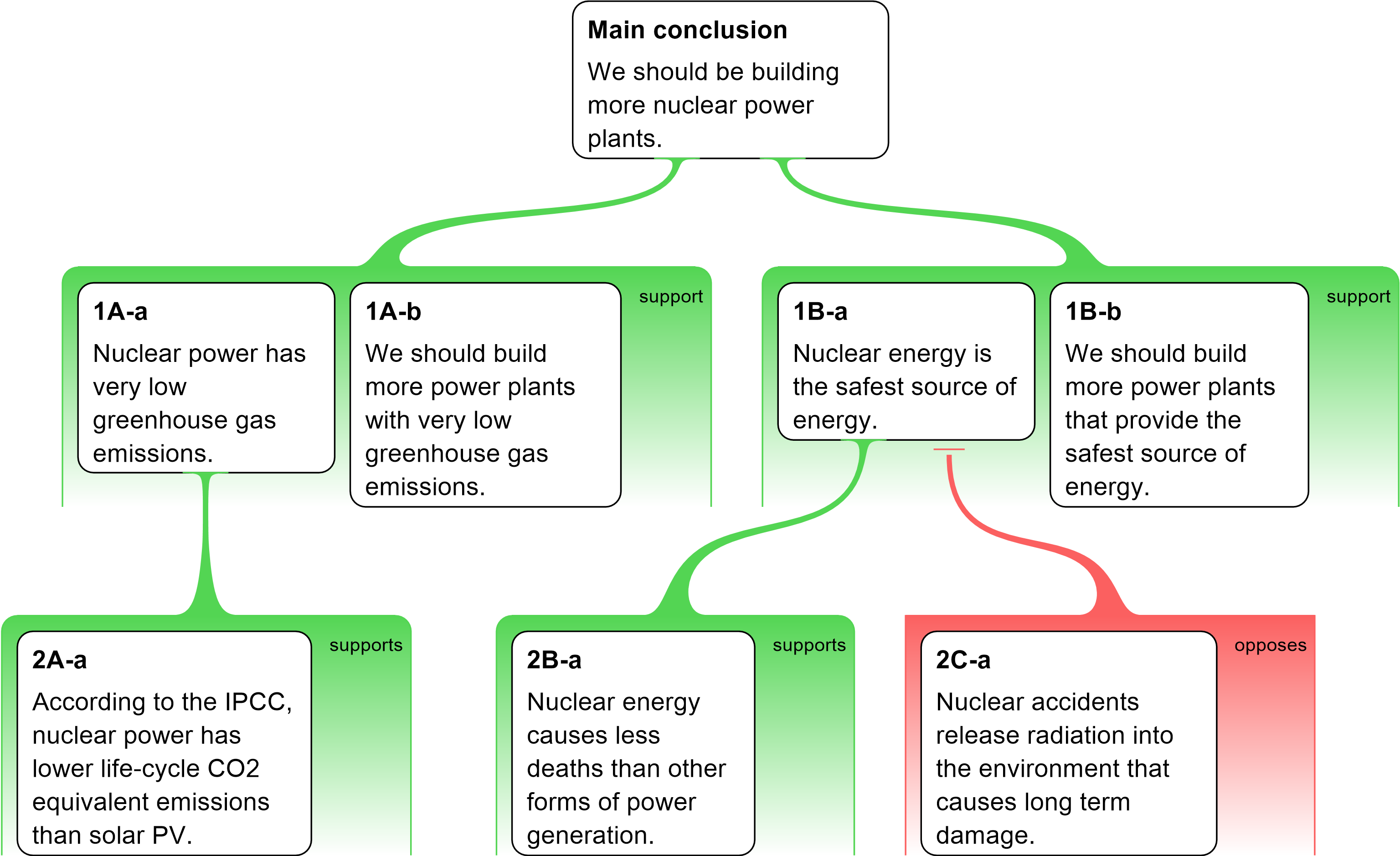

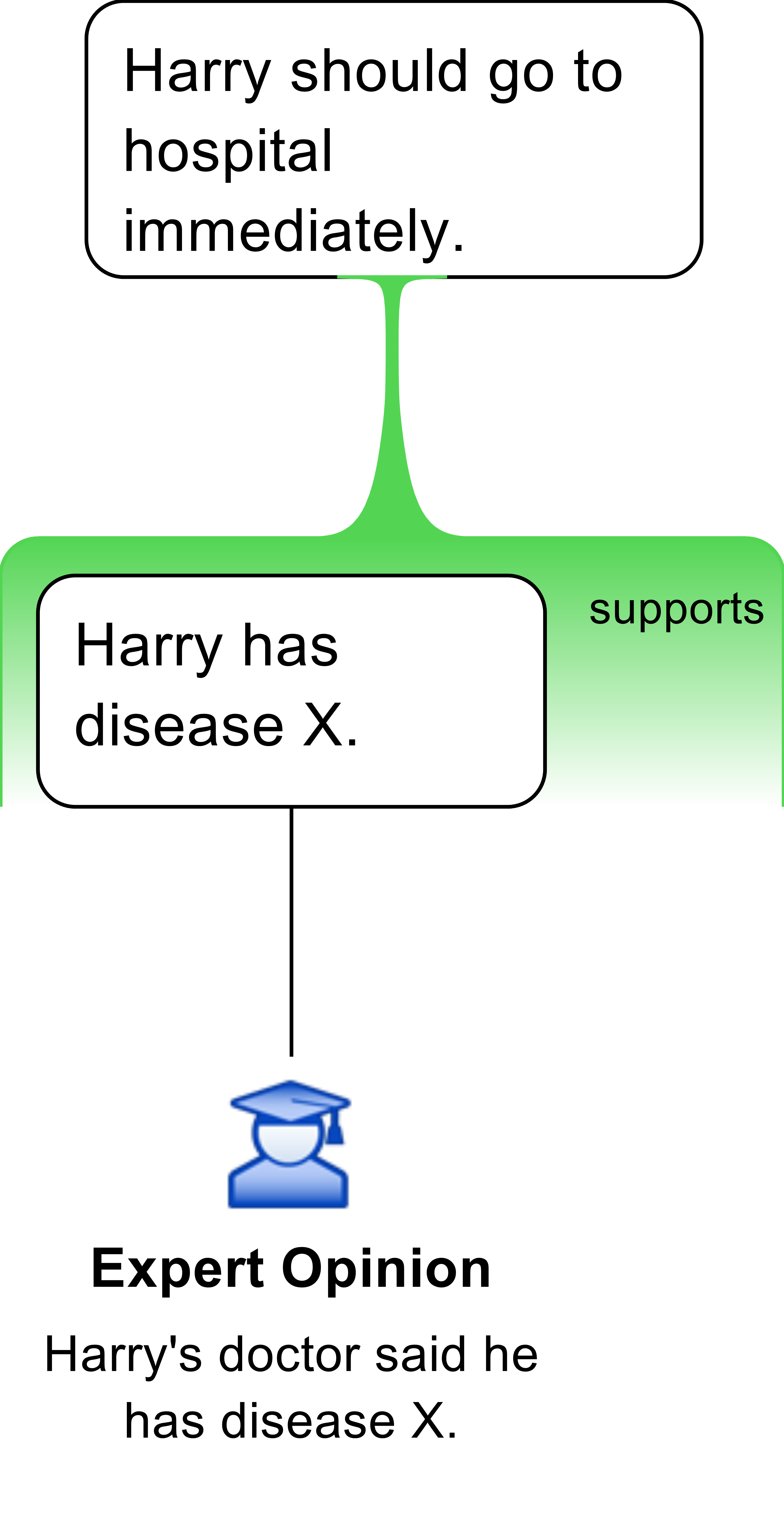

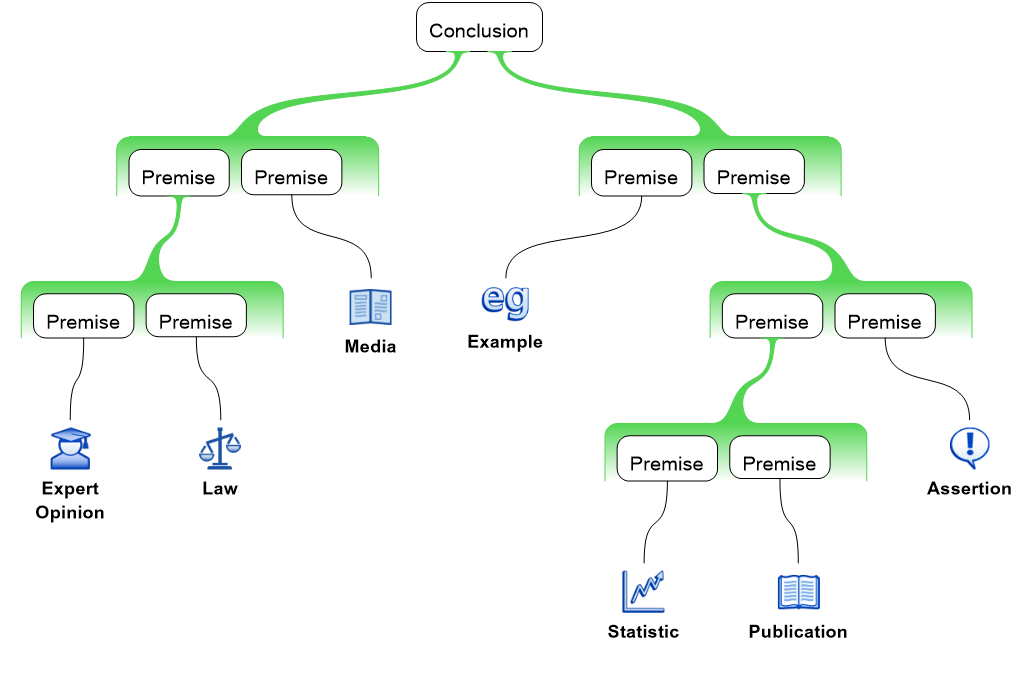

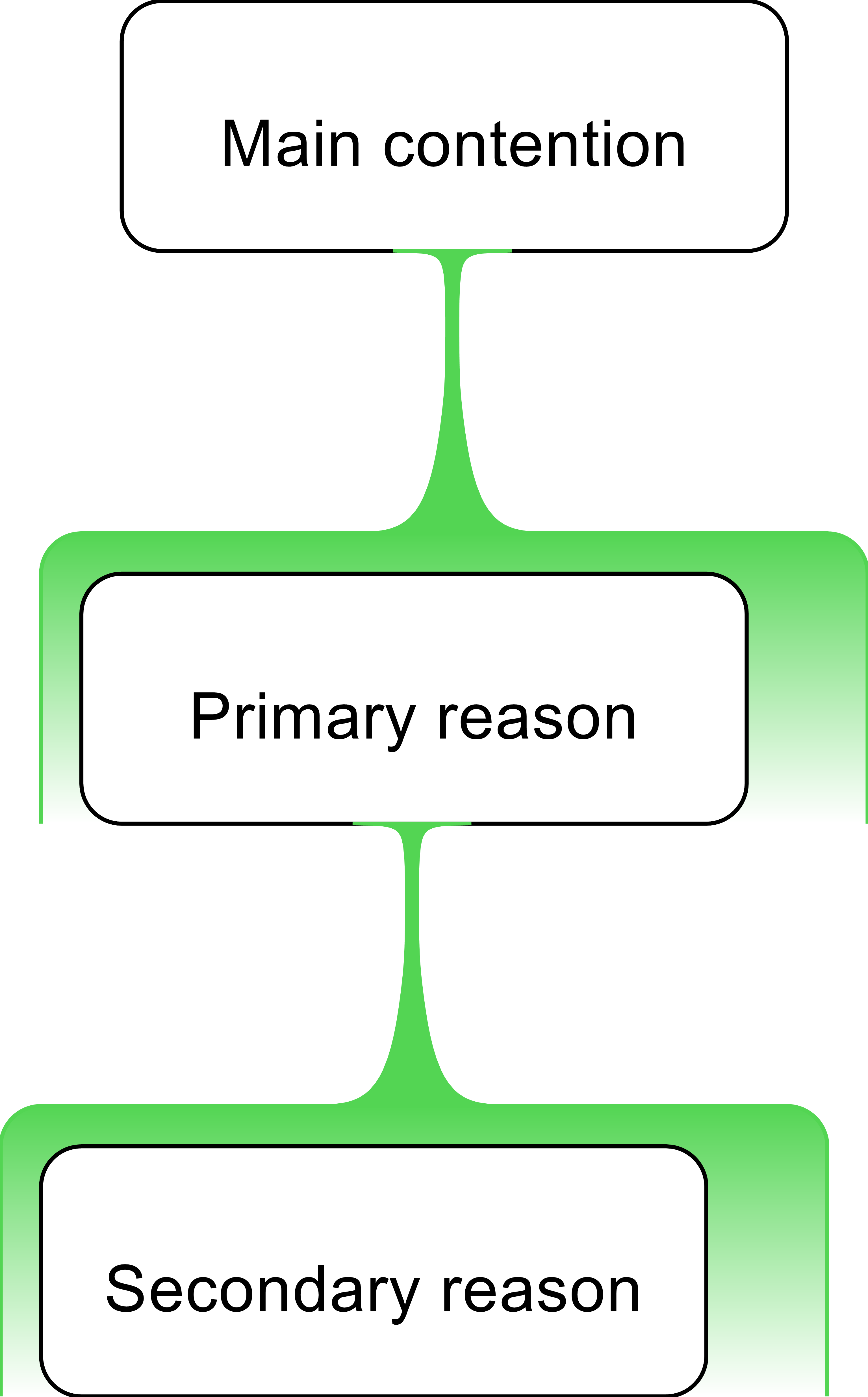

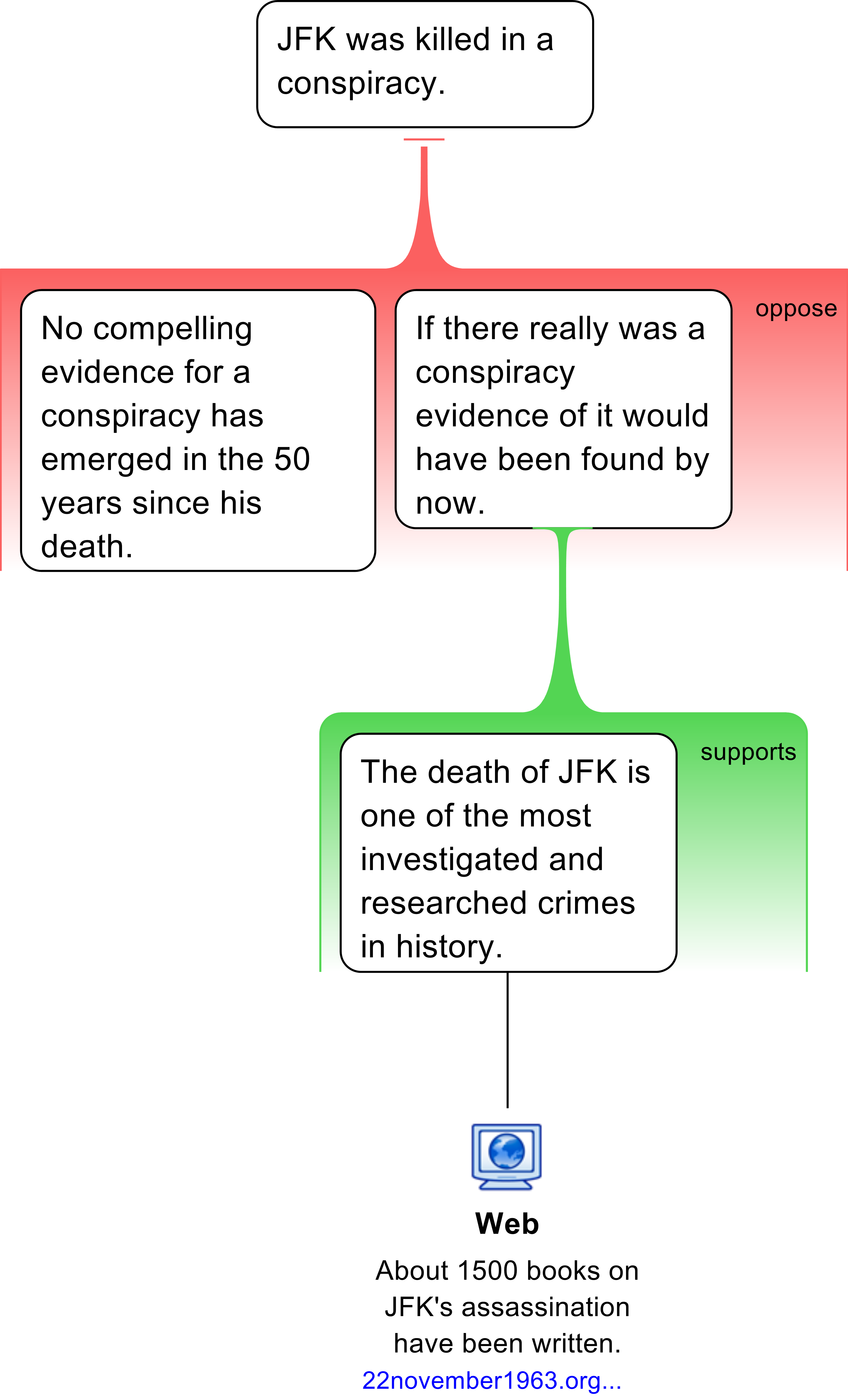

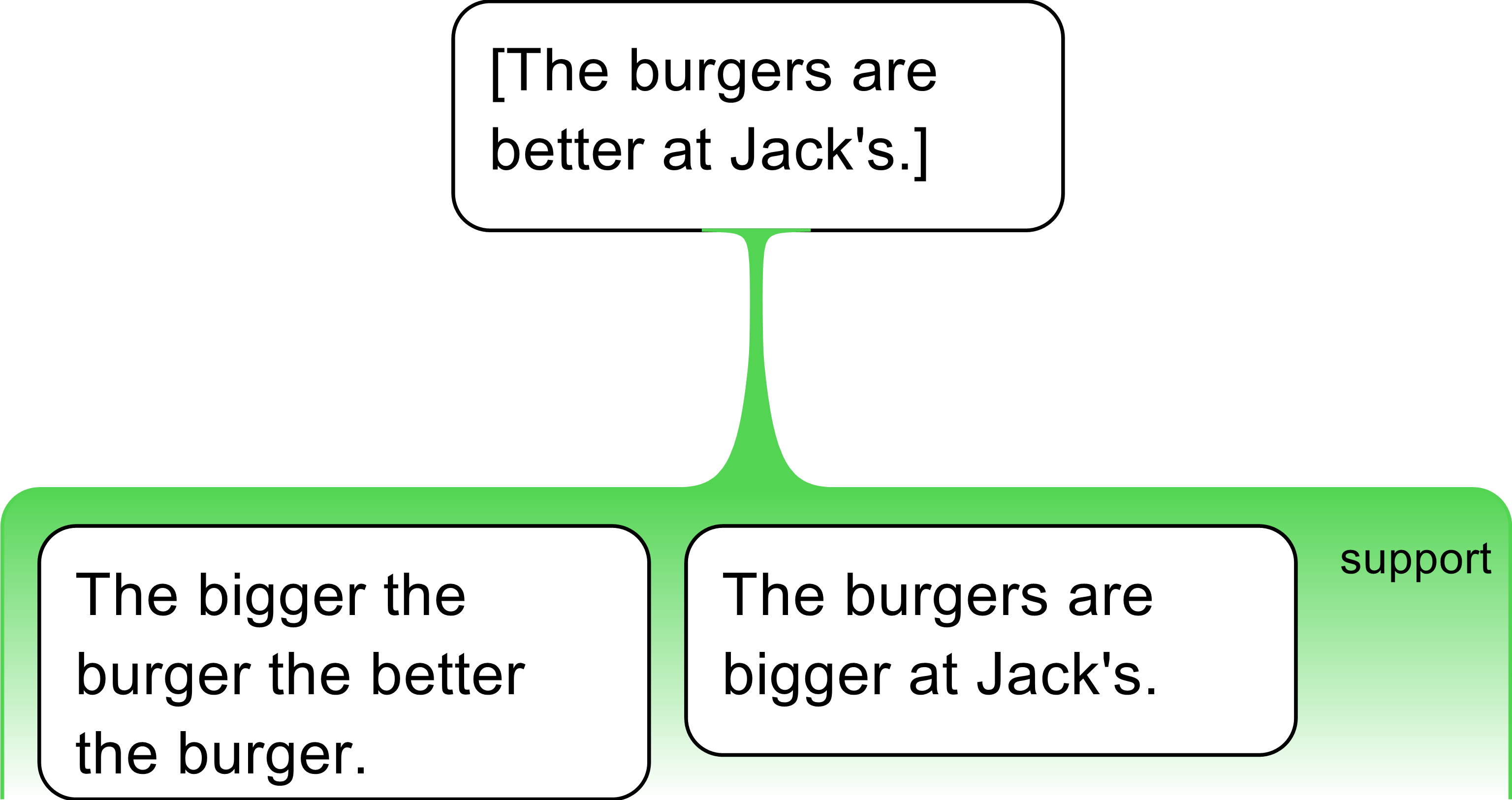

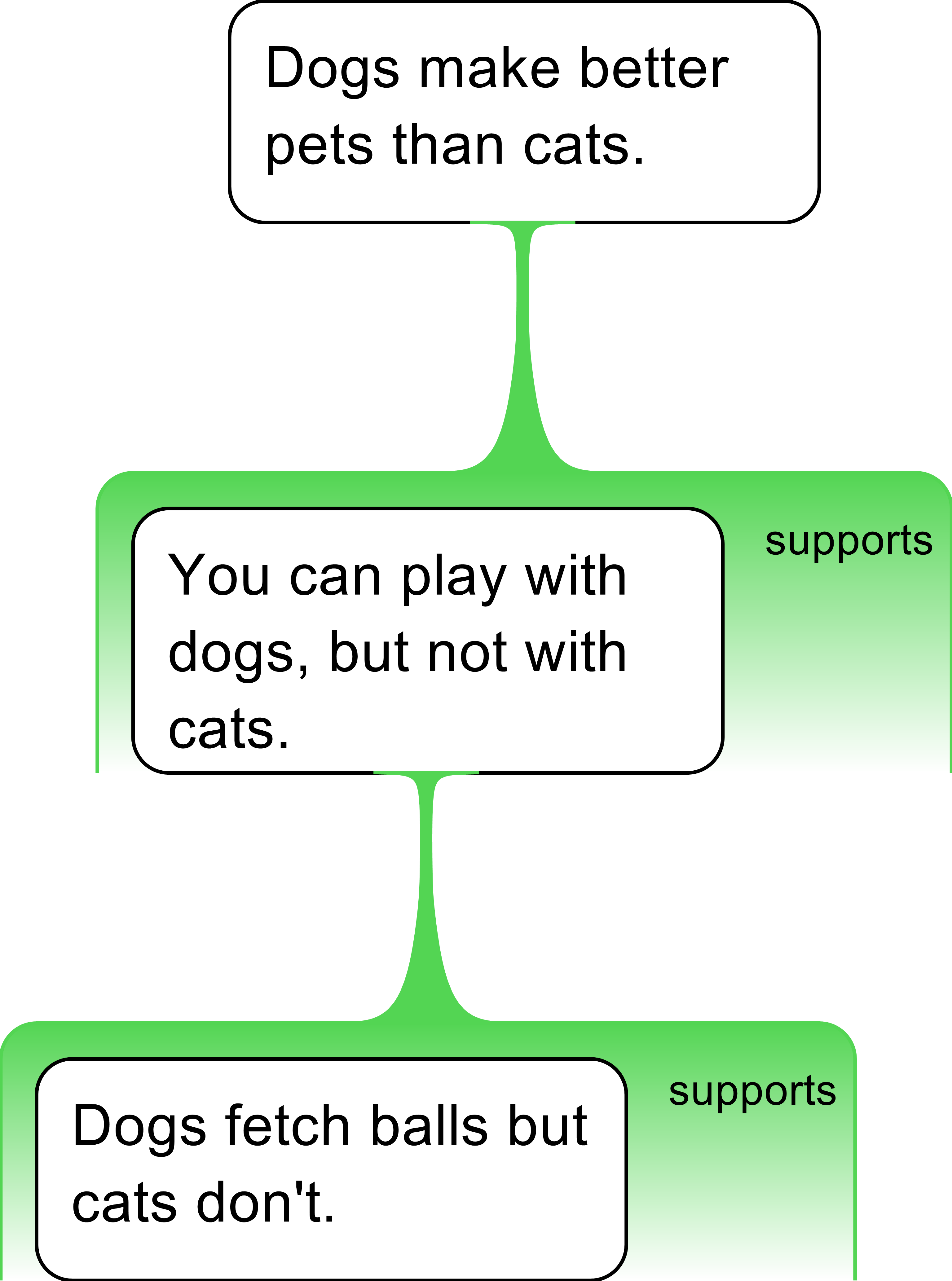

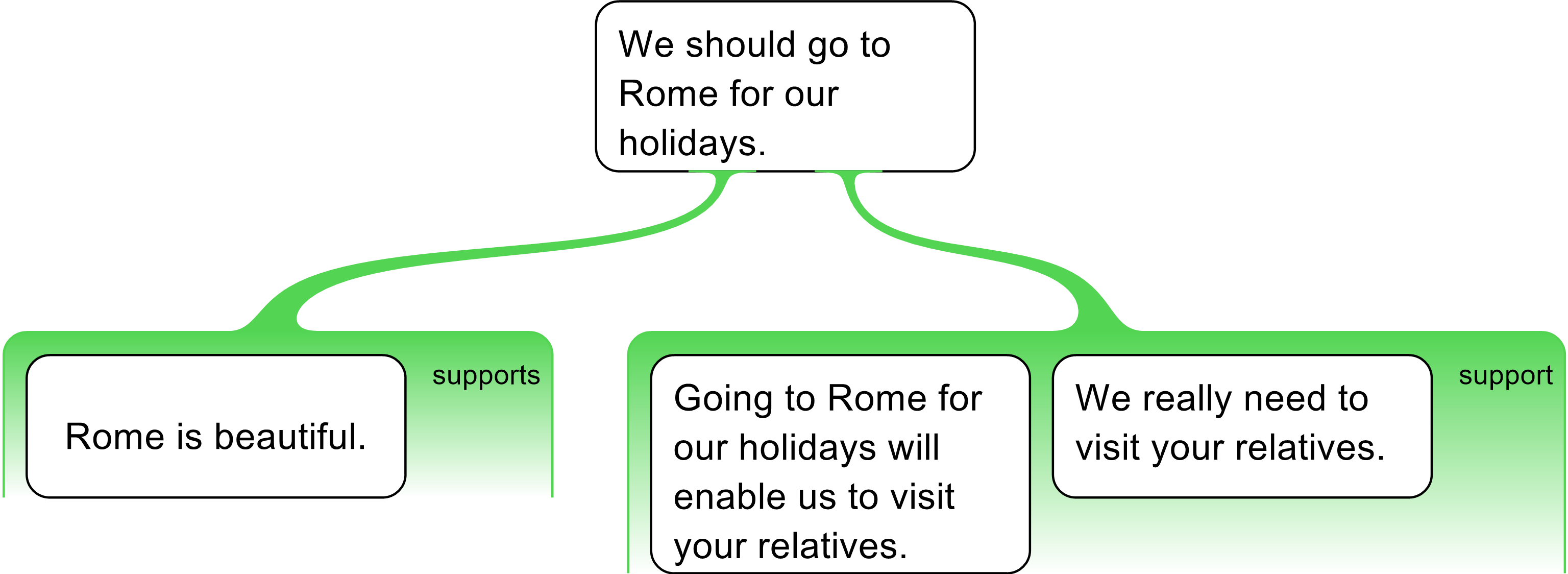

Figure 1. A short argument showing the main conventions used in argument mapping. The main conclusion is placed at the top of the map. The reasons for the main conclusion are identified by green shaded areas connected by lines to the main conclusion. The main conclusion in this example has two reasons, 1A and 1B. Inside the green shaded areas white claim boxes are used to display individual premises. Premises are placed in separate premise boxes because each premise needs its own justification. The surrounding green reason envelope effectively groups together linked premises working together to form a reason for the conclusion. Argument maps clearly show which premises of a reason are supported by further reasoning. For example, 1A-a is a premise, which is itself supported by a reason, 2A-a. As claim 1A-a is both a premise in one inference and a conclusion in another it sometimes called an ‘intermediate conclusion’ or lemma. Objections to claims are identified by a red shaded area. In the map above, there is only one objection, 2C-a. NB: When colour cannot be used the labels to the right of the shading helps to designate reasons and objections (i.e., the words ‘supports’, ‘opposes’).

Argument maps can

also

help

students

evaluate

reasoning

because

they

can

easily focus on eva

luating each inferential step of

an

arg

u

ment. These inferential steps are

indicated by the green and red

co

n

necting

lines

in the example provided. Students using

argument ma

p

ping

software can easily

see

how their evaluation of each step affects the conclusion. For example, i

n

the argument

in figure 1

, suppose the objection

in red is

strong

enough

that

we can no longer accept claim

1B-a

in the reason above it. That would mean that the

second

reason

given for the contention

(formed by

claims

1B-a

and

1B-b

)

no longer offers any support for the con

clusion

.

However,

the

first

reason (formed by

claims

1A-a

and

1A-b

) is

unaffected by the objection and

may

still be strong enough to

establish

the conclusion.

A map makes this very intuitive.

It is much harder to see the implications of chan

g

ing premises using prose

alone

and without the visual markers pr

o

vided by mapping software.

One of the main pitfalls when using argument mapping in teaching is

that

student

s

may find the level of rigor and clarity encouraged by the tec

hnique to be onerous.

However, u

sing

interesting examples that increase the demands of the

argument mapping

course

gradually

and incrementally

allow

s

students to have fun exploring how different argument

s

work

.

In most argument mapping software

students

can

freely move the parts of

an argument around and experiment with d

ifferent logical structures. This

ability to “play around” with an a

r

gument allows students

, over time,

to gain a deep and

practiced

u

n

derstanding of the structure of arguments

—an important aim of any critical thinking course

.

Anecdotally, i

t also helps with

student

e

n

gagement: by

manipulating parts of

a map using a software, partic

i

pants

more actively

engage

with critical thinking tasks

than they would do otherwise (i.e., if maps were not being used)

.

From an instructor’s point of view, adapting a classroom to teach critical thinking using argument mapping requires flexibility, and a

willingness

to experiment and

try out

new methodologies and princ

i

ples. Some of these are covered in this paper. Fortunately

, a variety of s

oftware and

the

exercises needed to run an argument mapping course are available

for free

online.

We return to these later.

Computer-aided argument m

apping

Computer-aided argument mapping (CAAM) uses software programs specifically designed to allow students to quickly

represent

reasoning using box and

line

diagrams.

This can, in principle, be done without software

(Harrell, 2008)

, but the software makes it much easier.

Bo

x

es are used to contain claims and

line

s

are used to show which claims are reasons for other

s

. The software does no

t itself

analyze

argume

n

t

ative

text

s

, or ch

eck the validity of

the

argument

s

, but by making argument maps students

can,

with practic

e,

get better at argument analysis and evaluation

.

In terms of entry-level skills required to use CAAM, little more is needed other than a solid understanding of the target language, basic computer skills, a broad familiarity with the importance of critical thinking, and a willingness to experiment with argument mapping software. In terms of achieving

expertise

in using CAAM, however, a rigorous approach to text analysis is involved, along with adoption of a number of CAAM methodical principles, and of course, the help of a dedicated and experienced instructor. Lots of argument mapping practice (LAMP) is also recommended

(Rider & Thomason, 2008)

.

The theoretical basis for argument mapping

improving

critical thinking skills

is based on two principles:

- It takes for granted the well-established notion of dual coding as it is understood in cognitive science. Human information processing is enhanced by the use of a number of sensory modalities. Diagrams and words allow better cognitive processing of complex information than words alone.

- It assumes the not unreasonable point that cognitive processing capacity in humans is limited, and that understanding complex arguments is enhanced by “off-loading” information as visual displays (in other words, it’s easier to remember and understand information if one can draw a diagram).

Argument mapping is similar to other mapping tools such as mind mapping and concept mapping. All attempt to represent complex rel

a

tionships. However, there are also important differences. Unlike mind mapping, which is concerned with associational relationships between ideas, and concept mapping, which is concerned with relational co

n

nections between statements and events, argument mapping is princ

i

pally concerned with inferential or logical relationships between

claims

(Davies, 2011)

. There is a difference between argument ma

p

ping and various diagrammatic representations in formal logic too. Argument mapping is concerned with representing informal, i.e., “r

e

al world”, or natural language argumentation. It thus contrasts with the use of diagrammatic techniques such as Venn diagrams as used in formal logic. In an important sense, argument maps should make i

n

telligible what is going on in arguments as they are (imperfectly) e

x

pressed in prose.

As noted,

a

rgument mapping

software provides several benefits in the classroom. The software makes building

argument maps

easy, so teachers can provide their students with many practical exercises to work on. Because the software allows the students to edit their maps freely, they can

engage in sel

f-directed exploratory learning

as they try out different argument structures to see what works best.

Argument maps

also

show the anatomy of an argument more clea

r

ly than can be done in prose

. By seeing models of

well-

constructed map

s,

students can

appreciate

how all arguments are made up of claims and how some of these

work together as co-premises. They can see

at a glance

how claims

belong to separate

line

s

of reasoning, and

can see why some claims are necessary for an argument to su

c

ceed and why some are not.

For example, o

ften

when

students

are presented

with a range of

re

a

sons for a conclusion

in prose

, they will focus on

counting the mi

s

takes and erroneously think that the

side of the debate

that

made the most number of outrageous

mistakes must be wrong about the co

n

clusion. But

by

presenting the argument

in

the form of a map

illu

s

trate

s

the point that

these bad

reasons

neither increase or decrease

the reliability of a

conclusion, and hence

are irrel

evant to our final eval

u

ation. Instead, attention needs to be

focused

on the

strongest

reasons, not the number. It i

s

possible that

the

side

of an argument

that pr

e

sented

the worst reasons for a given

conclusion

also provided

the most

conclusive

reason

(s

ee figure 2).

Argument maps can make discussing complicated arguments in a classroom much easier too. The number of reasons or objections to a contention can be easily “read-off” an argument map (this is difficult to do with a prose equivalent). Example arguments can be displayed on the projector and the teacher can point precisely to the part of the argument that he or she want to discuss. When debating issues in a classroom using argument maps can help externalize and depersona

l

ize the debate so that the students are no longer arguing with one a

n

other in a competitive way but are collaborating on mapping an a

r

gument together in an attempt to construct the best argument for or against the conclusion. This promotes a sense of involvement in a joint scholarly enterprise.

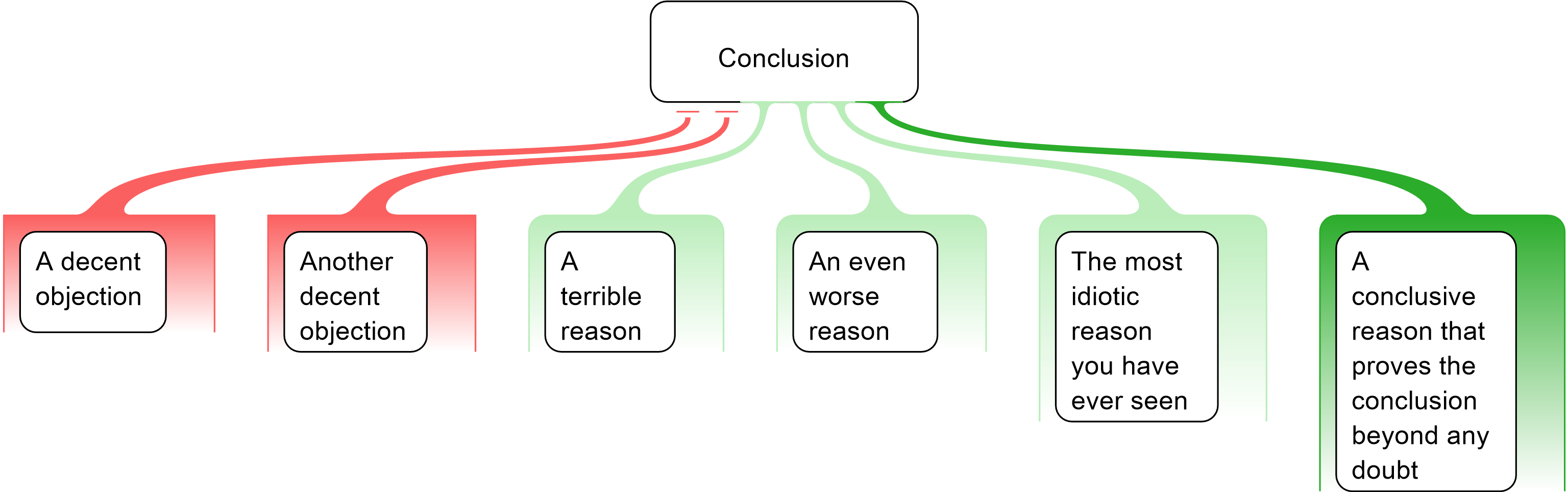

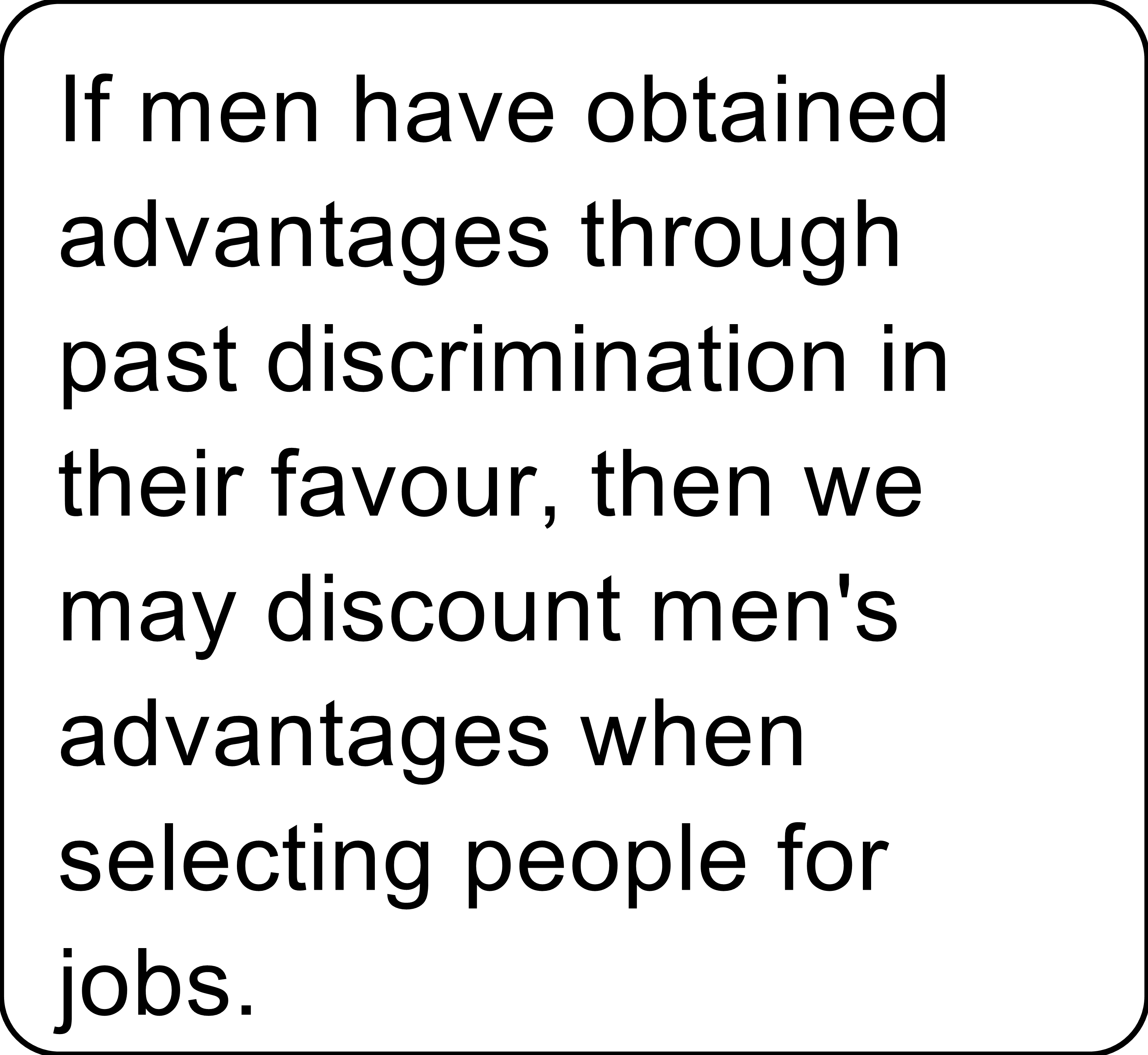

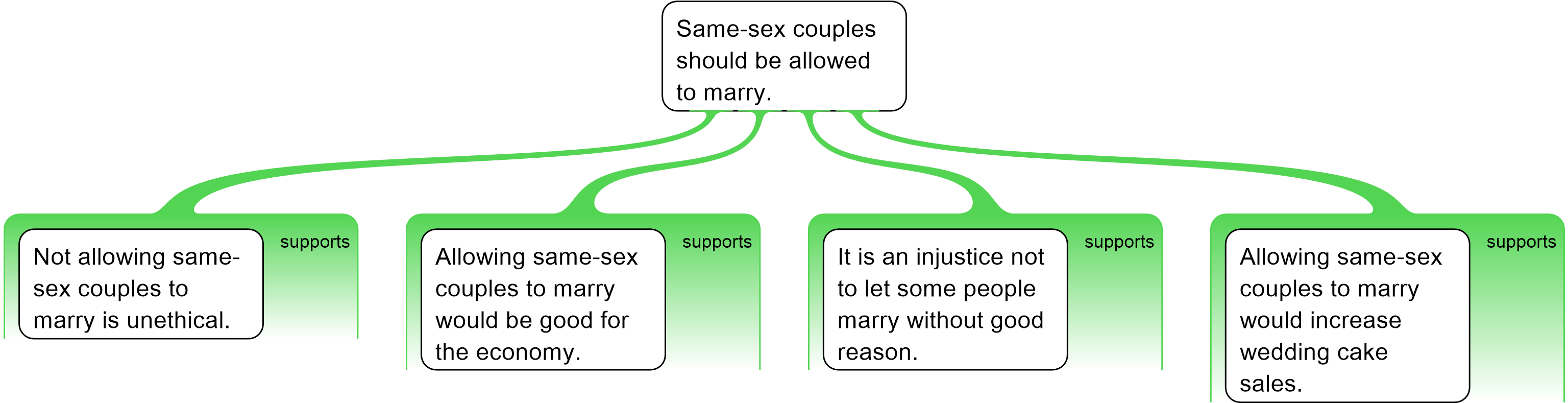

Figure 2. Argument maps clearly distinguish between separate reasons, so it easier to focus on the logical implications of the good reasons and not get distracted by the bad reasons that should just be ignored when it comes to evaluating the conclusion.

An additional benefit is this: Maps also make assessing student’s reasoning skills much easier in assignments, because the teacher can clearly see what his or her students had in mind without the confounding variables to be found in an argumentative essay (Davies, 2009). Also, asking the students to make an argument map prior to writing an argumentative essay can also help ensure that the basic structure of the argument is adequate before they start writing. For a number of reasons, this can assist in the process of essay writing.

Teaching using computer-aided argument mapping

Let us now look at

how to teach critical th

inking using argument mapping

.

Some of these point

s

apply to any

informal logic or

critical

thinking class, but they are particularly

relevant

to any class intending to use argument mapping

as a teaching tool

.

The parts of an argument

In teaching students about argument mapping it is helpful to first di

s

t

inguish the following component parts of an argument

and to provide examples of each:

- contention/conclusion (a singular claim being argued for);

- reasons (a set of claims working together to support a conclusion or sub-conclusion)

- objections (a claim, or set of claims working together to oppose or undermine a conclusion, another reason, or an inference);

- inference (a logical move or progression from reasons to contention).

- Inference indicator words (a word or phrase that identifies a logical progression from reasons to a contention, such as ‘because’, ‘therefore’ or ‘it can be concluded that’);

-

Evidential sources taken as the endpoint of a line of reasoning

(arguments

must

end somewhere, and often this will be

a

source of information, e.g.

a media

report, or

an expert opinion

, that we expect people to accept without the need for additional arg

u

ment.)

Claims

A

rgument mapping concerns itself with relationships between claims or propositions. The first main challenge is to

discuss with students

the nature of claims. Experience in teaching argument mapping has

shown

us that students

find this concept problematic, a

nd

,

if students

are unclear about claims, they cannot

easily

create

argument maps.

How can the notion of a claim

be taught to students?

One might start with

definition

s

such as:

- A claim is a declarative sentence that has a truth value; or

- A claim is an assertion that can be agreed with or disagreed with (or partly agreed with).

O

ften

, however,

students find such

definitions difficult to grasp. It is best to start with examples of

simple

empirical statements

using the first definition above

.

M

odel claims

can be

instructive

here

, along with a discussion about

the

states of affairs

that

can

establish

if and whether

certain sentences can be said to be

true or false

(or empirica

l

ly uncertain)

:

- The door is shut. (This might be true, false, or empirically unclear, i.e., when viewed from an angle).

- Donald Trump was elected President of the United States. (This is clearly true, and there are a number of facts that make it so.)

- Sally is at McDonald’s. (This could be determined by observational evidence and perhaps knowledge of Sally dining habits.)

-

Acid turns blue litmus paper red. (This could be determined by procedures used in the science of Chemistry.)

Students should then be encouraged to find similar claims in published literature. They should practice reading passages from texts, paying attention to whether the claims meet the standard criteria. The criteria are as follows.

Claims should be:

- Singular declarative sentences (i.e., not making more than one point);

- Complete sentences (not fragments);

- Precisely expressed with a potential truth value (not vague or ambiguous);

- Free of inference indicator words.

Once simple empirical claims are successfully used to clarify the notion of the claim, instructors can begin to use examples less reliant on a truth value, i.e., claims more subject to dispute and more likely to engender arguments. The second definition of a claim is apposite here: an assertion whichcan be agreed with or disagreed with (or partly agreed with). For example:

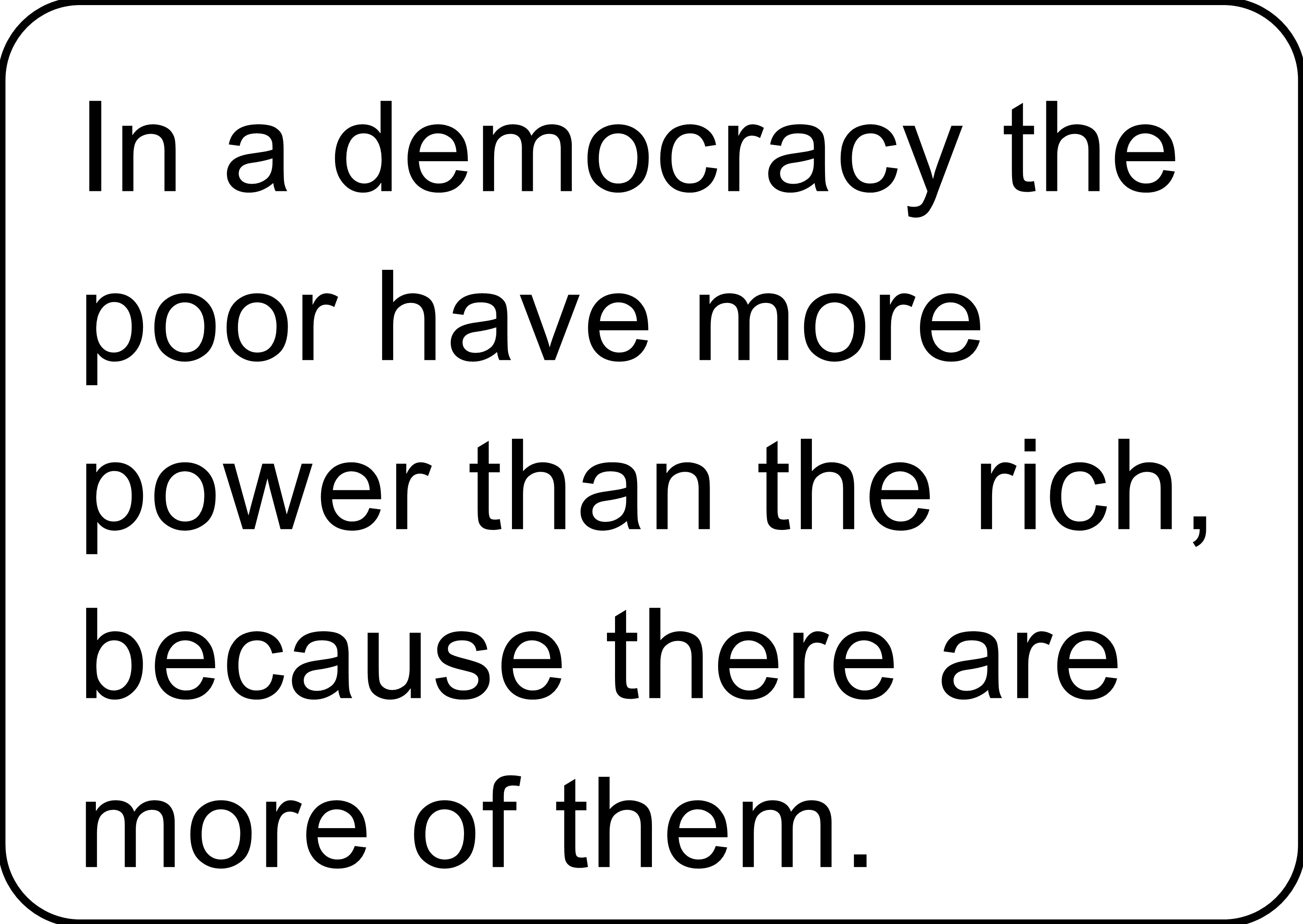

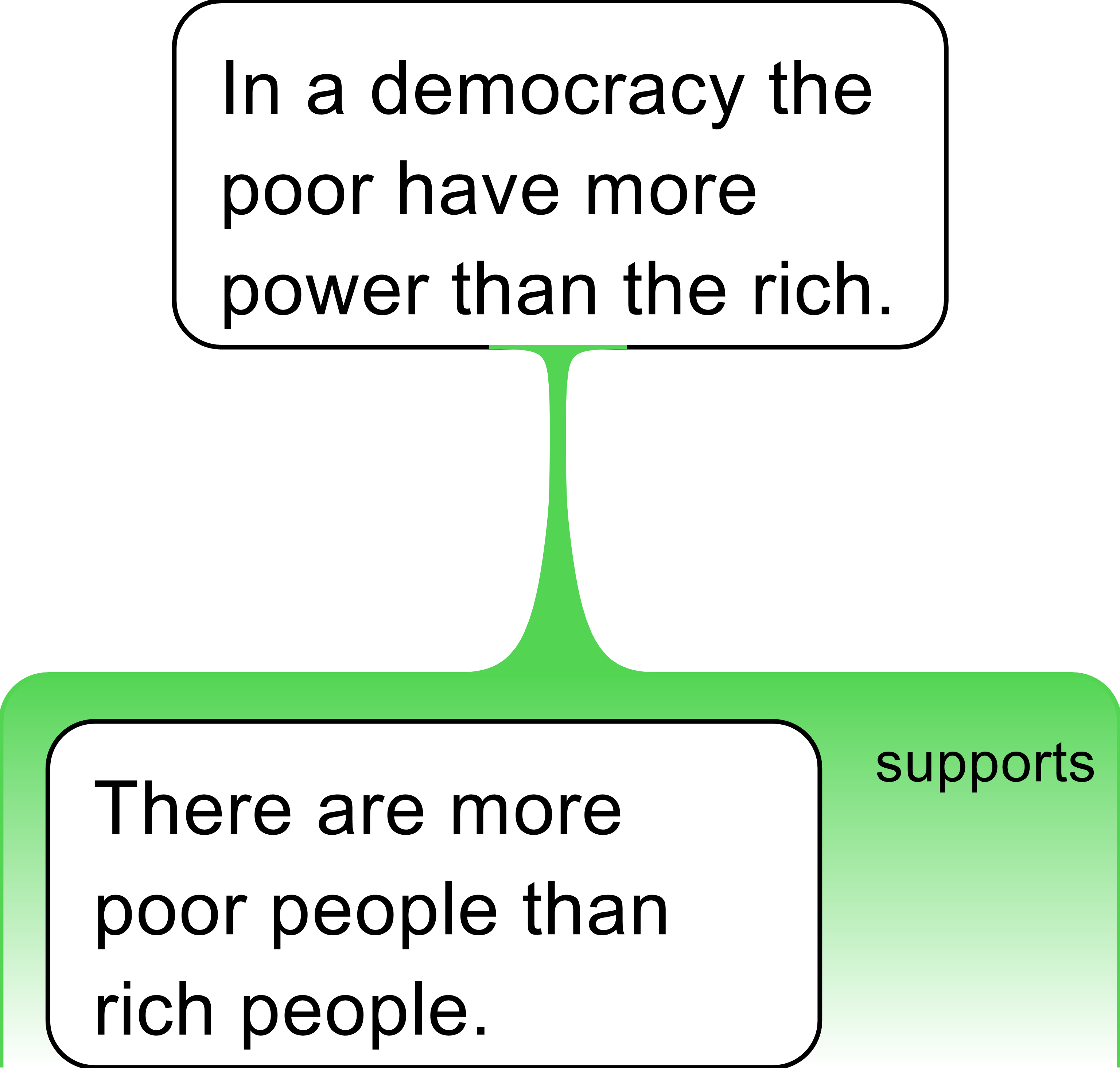

- In a democracy, the poor have more power than the rich.

This is not a simple empirical claim (there is no discoverable fact of the matter) yet it is a claim with a potential truth value—even if this is not easily ascertained. While not a claim with an empirical basis, the same criteria for claims still apply. Examples like this can lead to many useful departure points for instruction and debate.

Once appraised of the distinction between an empirical claim and a contestable claim, one can introduce the distinction between claims and reasons. This is where inference indicator words become important. For example, it would be a mistake to include the following inference as a single claim in an argument map, because it contains two claims connected by the inference indicator ‘because’.

- In a democracy the poor have more power than the rich, because there are more of them.

i

.e., not

:

but

instead:

It should be madeclear to students that there should be no reasoning going on inside a claim box. Students should watch out for typical inferenceindicator terms that occur in passages of text such as: so, since, consequently, therefore, as a result/consequence, in view of the fact that, as shown by (see Table 1,below). These terms are represented as relationships between the claims and their location in the maprather than in the premise boxes themselves.Becausein this example becomes an inference indicator (not part of the statement), and any claims in boxes are rendered as complete sentences (not fragments). This is important to stressbecause the argument mapping software doesn’t check what the students put into the claim boxes. Without instructor input, students can create unintelligible maps because they put either multiple claims into each box or ungrammaticalor fragmentary sentences that don’t have a potential truth value.

It is also important to make clear to students that claims are not questions, commands, demands, exhortations, warnings, and so on. Shut the door! (a demand) is not a claim as it is not potentially true or false. Similarly, interrogative forms such as: Is Sally going to McDonald’s? is not a claim. (One cannot ask: Is the question: Is Sally going to McDonald’s? true or false?) By contrast, one can establish the truth of the assertion: Sally is at McDonald’s. Practice should be emphasised in establishing claims in key passages of text, identifying non-claims, and turning non-claims into claims.

It is generally helpful to make sure that claims are singular statements and do not include conjunctions (e.g., and, but, moreover) though there is nothing logically wrong with putting conjunctions into an argument map. Conjunctions are permitted in a single claim box if they expand or elaborate on a singular claim rather than add another. If they add another claim they must be treated differently. For example, take Socrates is a man but he is not famous. This is two separate claims: Socrates is a man AND Socrates is not famous—the first true; the second clearly false, and in an argument map we generally shouldn’t conflate them. These would be represented in separate claim boxes.

It is also important to stress that claims are always complete sentences. They should also be clearly potentially true or false: “Reshine moisturiser may make you look better” is not even a potentially clear claim (how would one decide if it is true or false?) whereas the more precise “Reshine moisturiser will make all your wrinkles disappear from your face within 24 hours” is a claim that is much easier to verify or falsify. Moreover, it seems to beg a reason (e.g., that Reshine moisturiser might have exfoliate properties) and this suggests at least that there might be some science behind this. In the latter case, but not the former, there is—potentially at least—a fact of the matter that can be empirically determined. All claims can be mapped, but those with reasons and evidentiary support will inevitably be seen as much stronger—as they should.

The distinction between (a) simple empirical claims; (b) contestable claims that unclearly expressed; and (c) clearly expressed contestable claims which potentially admit of reasons that could be potentially true or false, is fundamental to argument mapping and time needs to be given to explore the differences.

These points are important to establish early in argument mapping as one of the ways in which students can fail to map arguments properly is either by (a) constructing a map without claims at all; (b) using unclear claims or truth-dubious claims; or (c) putting more than one claim inside a reason, objection or contention box. Any of these can lead to poorly constructed maps. Argument mapping can help students understand why these problems are important, but the software doesn’t assess students’ work for these problems. Some programs however offer online tutorials that cover some of these points.[3] Importantly, students should be given time to play around with the argument mapping software being used, and to practice putting claims into boxes. Simple examples of prose, e.g., from Letters to the Editor, advertising slogans, or extracts from academic texts can be used for this purpose.

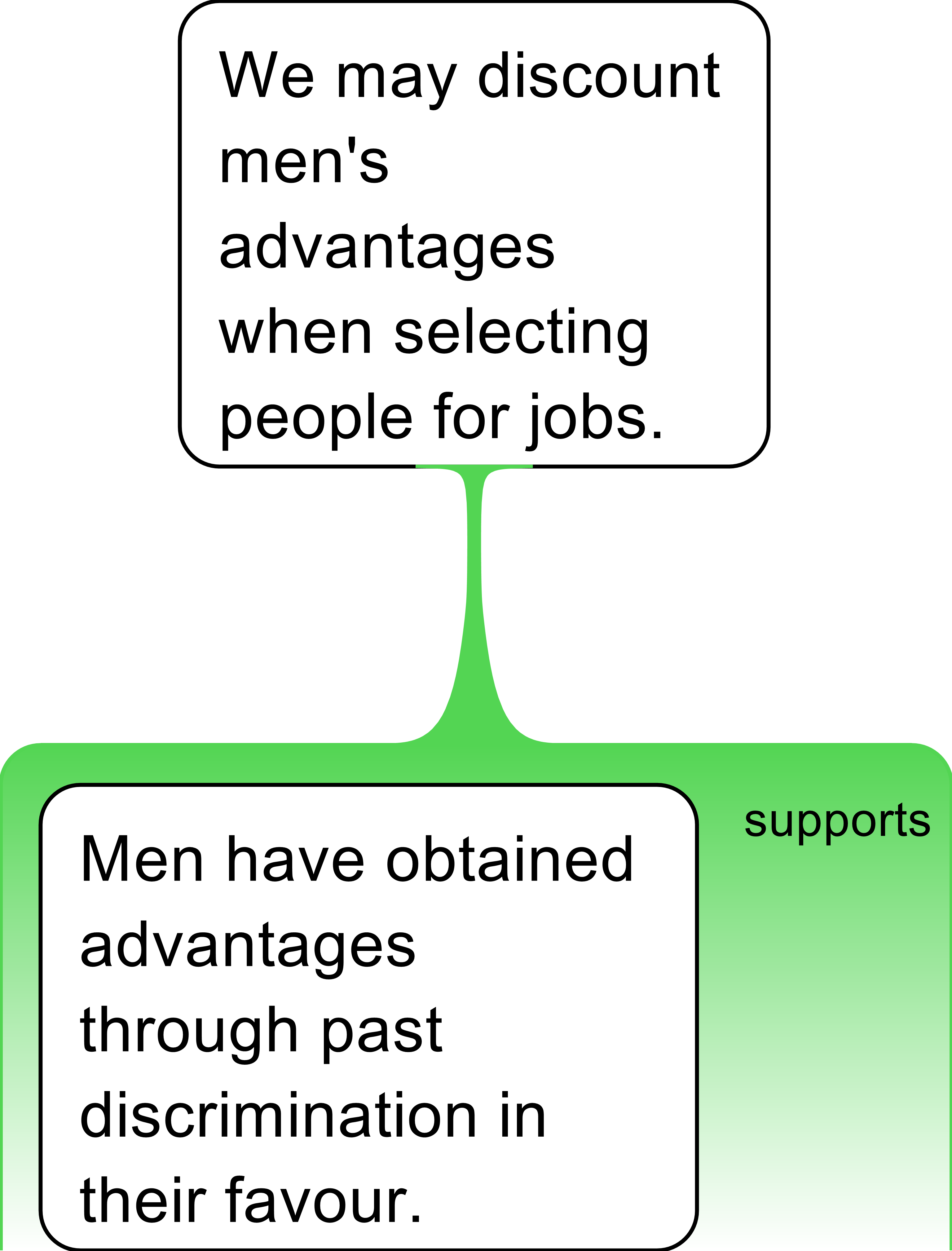

Sources of evidence and the provisional endpoints of arguments

Arguments and argument maps need to stop somewhere and where possible it is good practice to finish a line of reasoning with an evidence source that is uncontentious and can be accepted without further debate. Evidential sources come in many forms. For example, a person might accept the claim that he or she has disease x because they trust the expert opinion of their doctor. Evidence sources include assertions, data, common belief, case studies, legal judgements, expert opinion, personal experience, quotes, statistics, and so on. The argument mapping software Rationale™ allows users to represent sources of evidence as unique claim boxes that can be used to clearly mark the current endpoint of a line of reasoning (see Figures 3 and 4 below).

Of course, whether a source of evidence is uncontentious or not is provisional, and this provisional nature make the notion of an endpoint to an argument difficult to teach to students. Teachers need to make the point clear to students that context matters when deciding if a particular source of evidence can be used as an endpoint in an argument. It is probably fine to take the testimony of one’s housemate that there is no milk in the fridge, but it is not acceptable to take for granted the assertion that Donald Trump is a part of a conspiracy of reptilian space aliens trying to take over the planet. It probably helps to reassure students that deciding on an acceptable endpoint to their argument is a very difficult thing to do and they can always revise their argument map at a later point in time if they tied off a line of debate too quickly.

Figure 3. Example of source of evidence used to end a line of reasoning. The argument mapping software Rationale™ has unique icons for different sources.

Arguments

Once the notion of a claim is clear, the concept of an argument needs to be introduced and applied using CAAM software. The notion of an argument, like the notion of claim, may also need some explanation. An argument qua an unpleasant interpersonal quarrel between individuals, is in such common use that it can be hard for students to see the alternative. The philosophical concept of an argument is typically defined as a connected series of claims intending to establish some conclusion, or variations on this, e.g., a sequence of claims with an inferencei.e., a logical move, to a conclusion/contention. Students should be taught to appreciate that while claims are singular propositions only, arguments are—by definition—claims for which reason(s) are given.

Figure 4. Ideally, a good argument map requires all premises to be either supported by further reasoning or provisional sources of evidence.

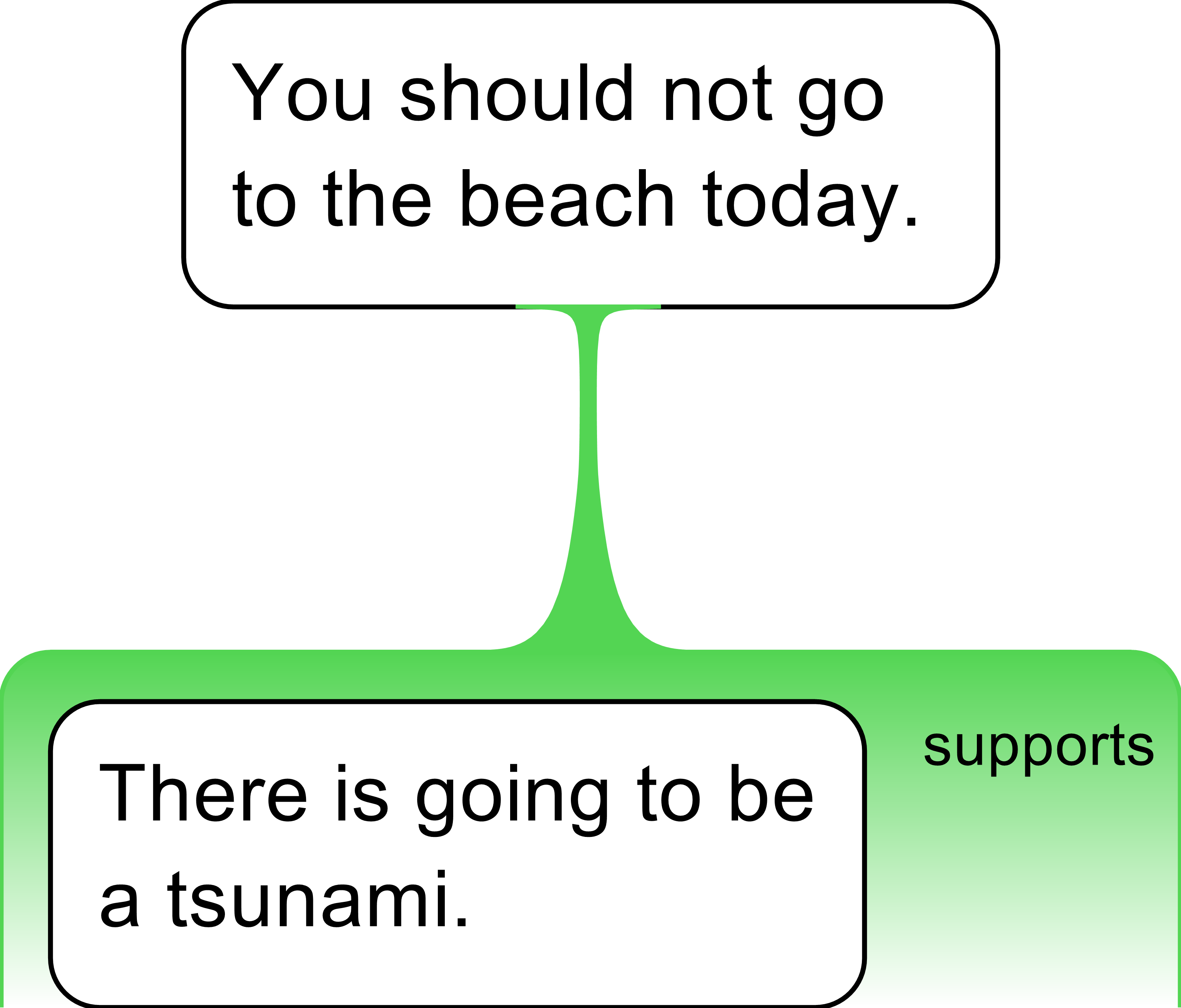

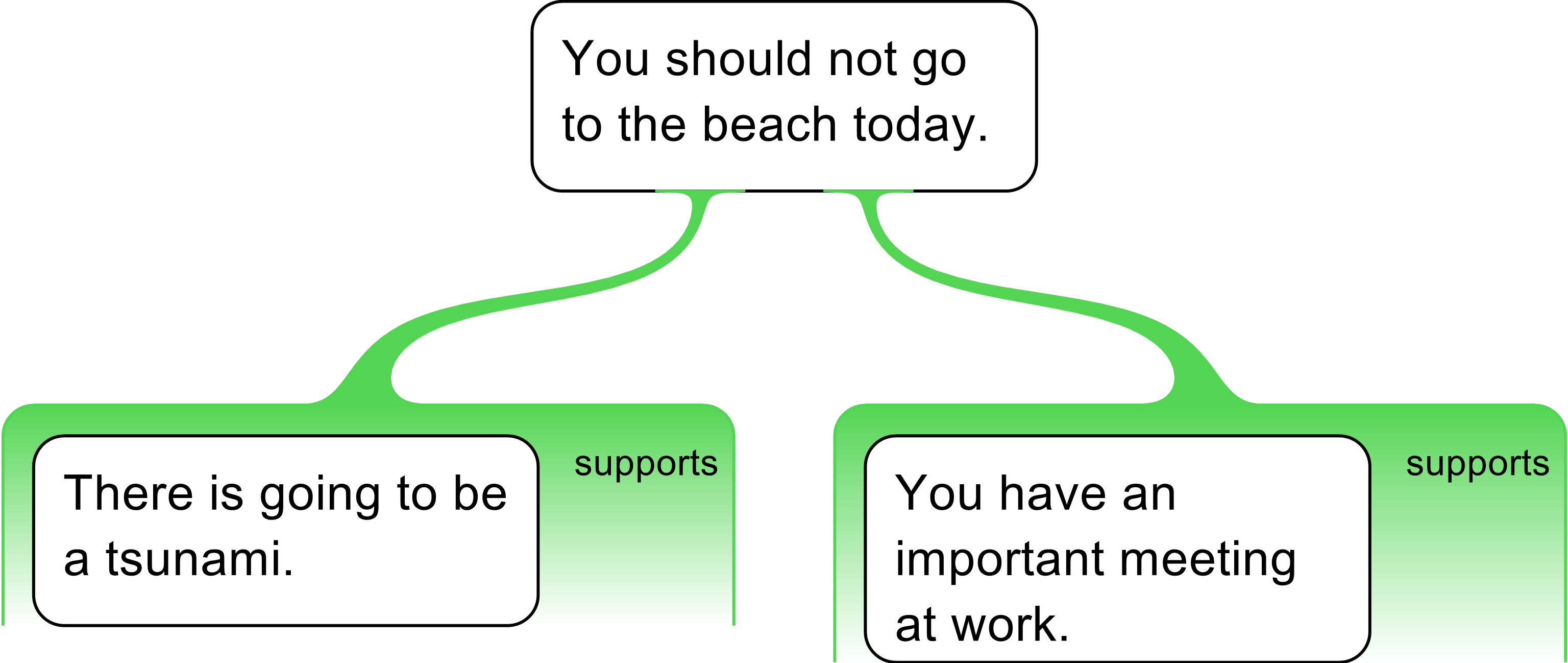

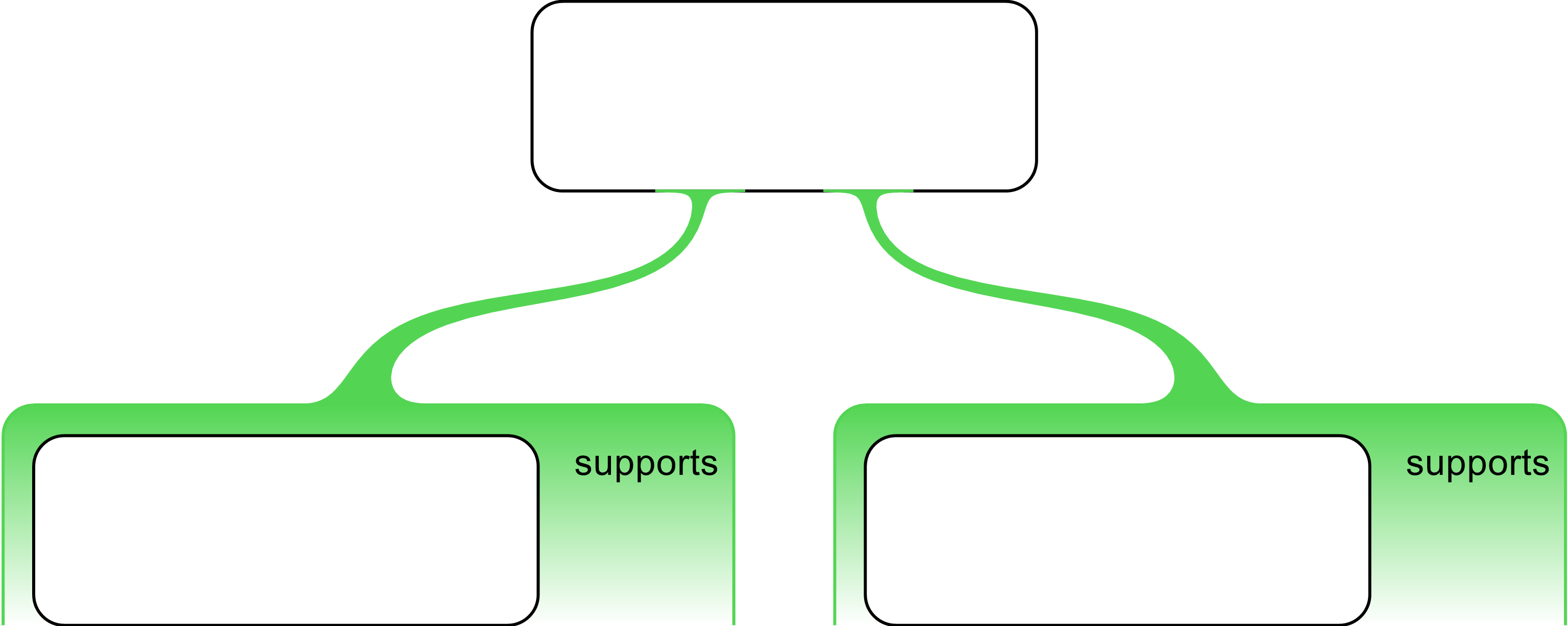

Simple, Complex and Multi-Layer Arguments

Early on, the distinction between simple and complex arguments should be made clear. A simple argument is one for which a single reason is given; a complex, or multi-reason argument—as the name suggests—is one with a set of reasons supporting a contention. Here is an example of each:

Simple argument with a single reason

Complex argument with more than one reason

A key pitfall for students is in telling whether an argument has separate reasons working independently (as in this last example) or whether the reasons work together as dependent co-premises. We return to this later.

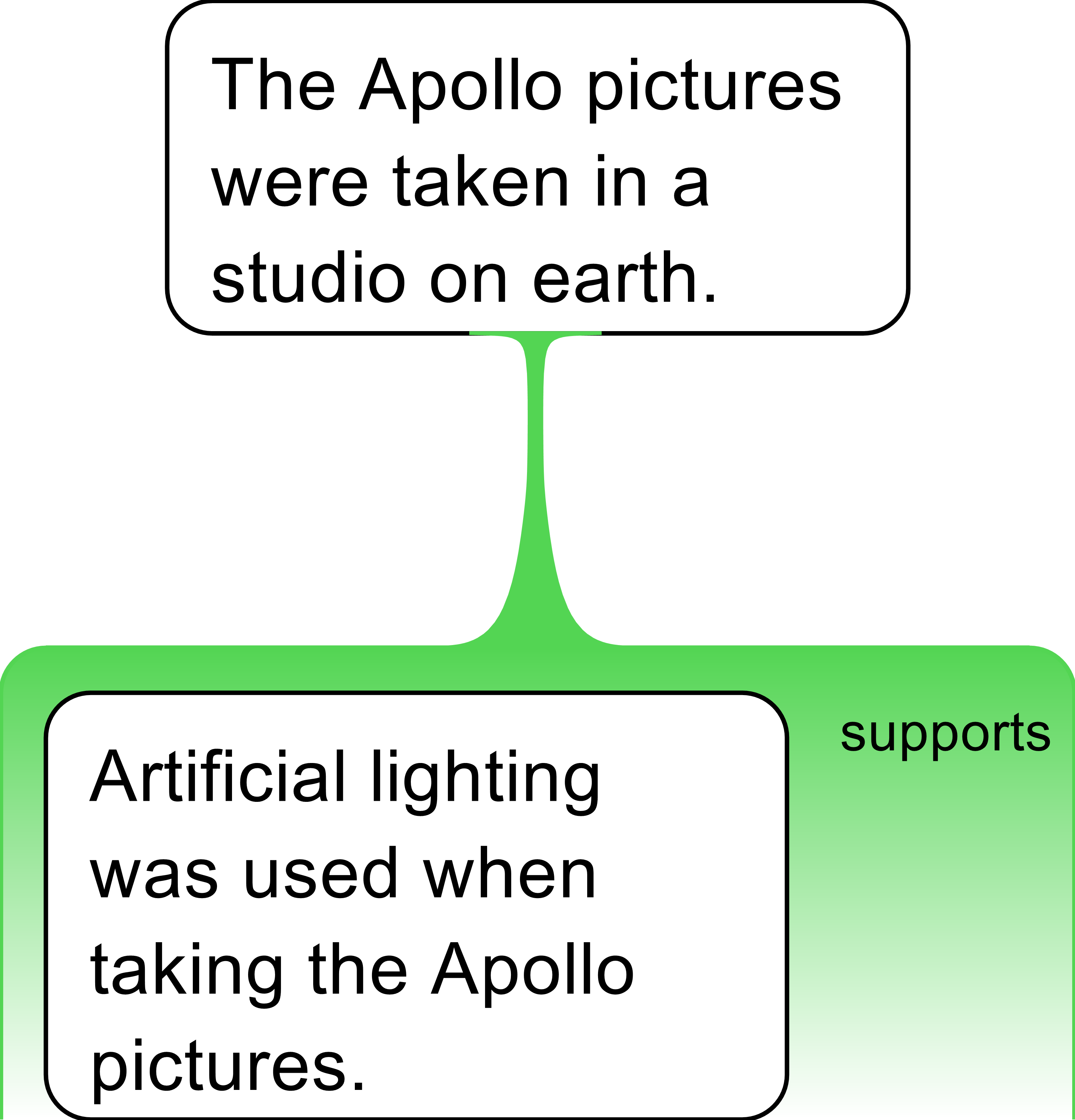

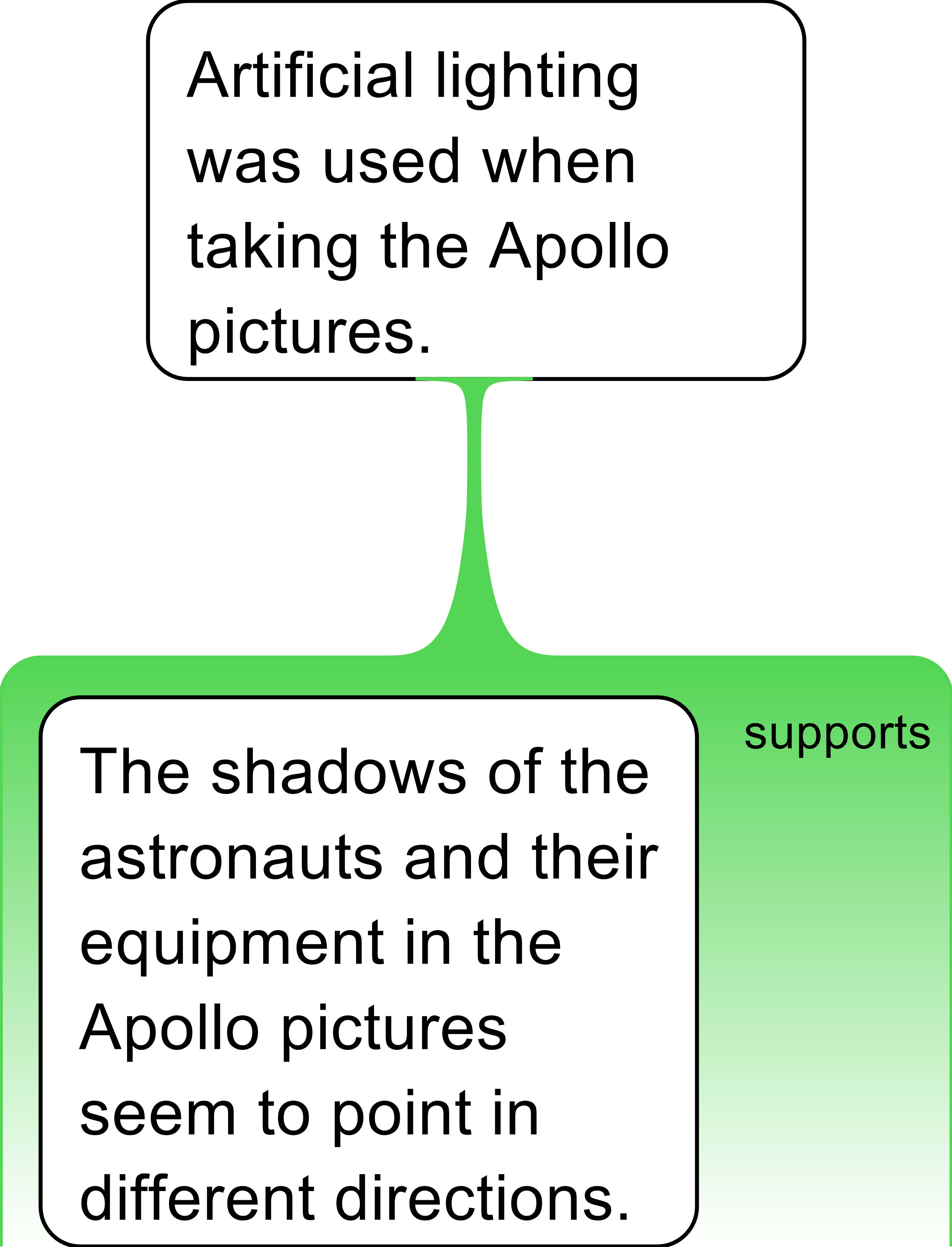

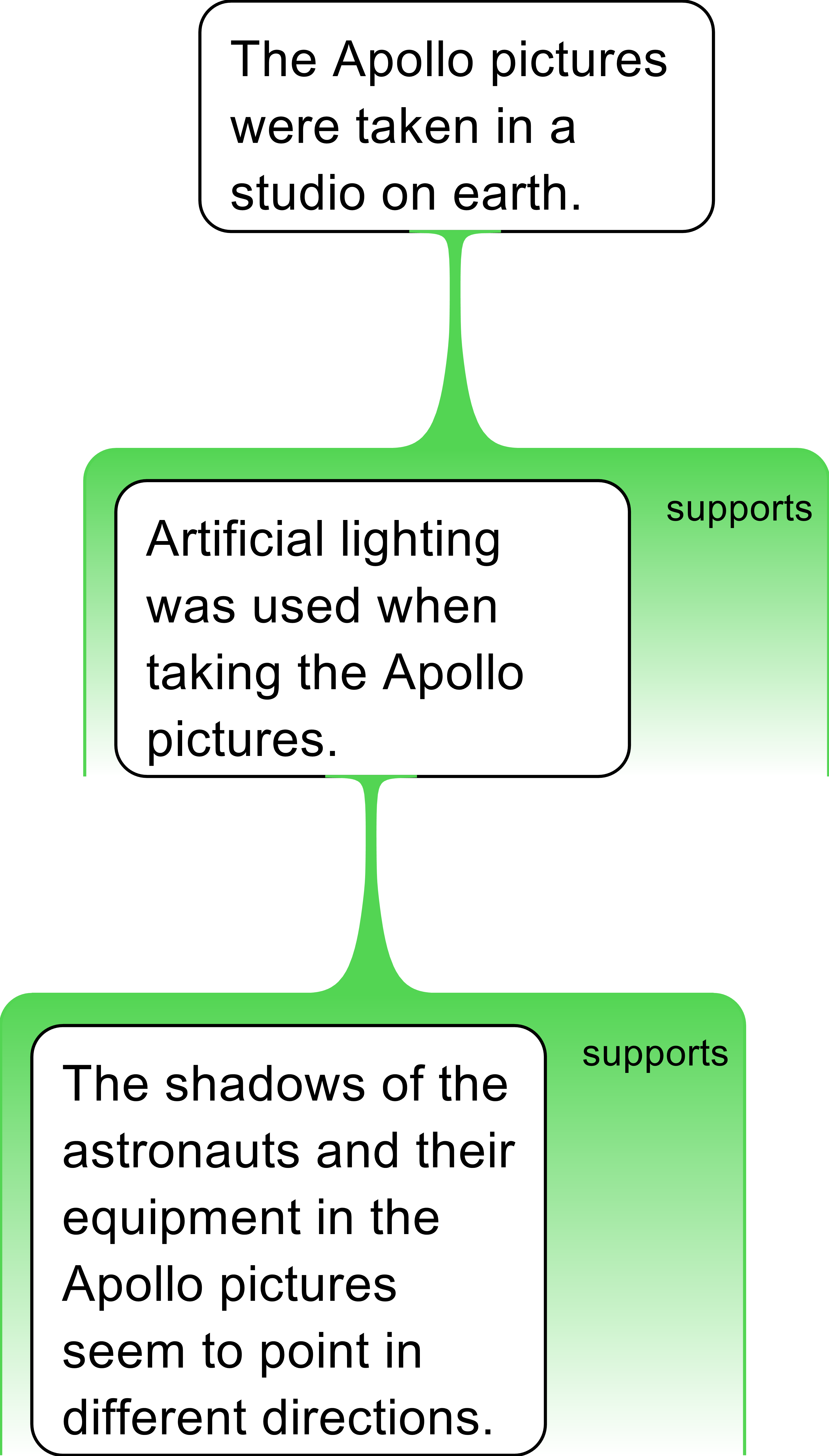

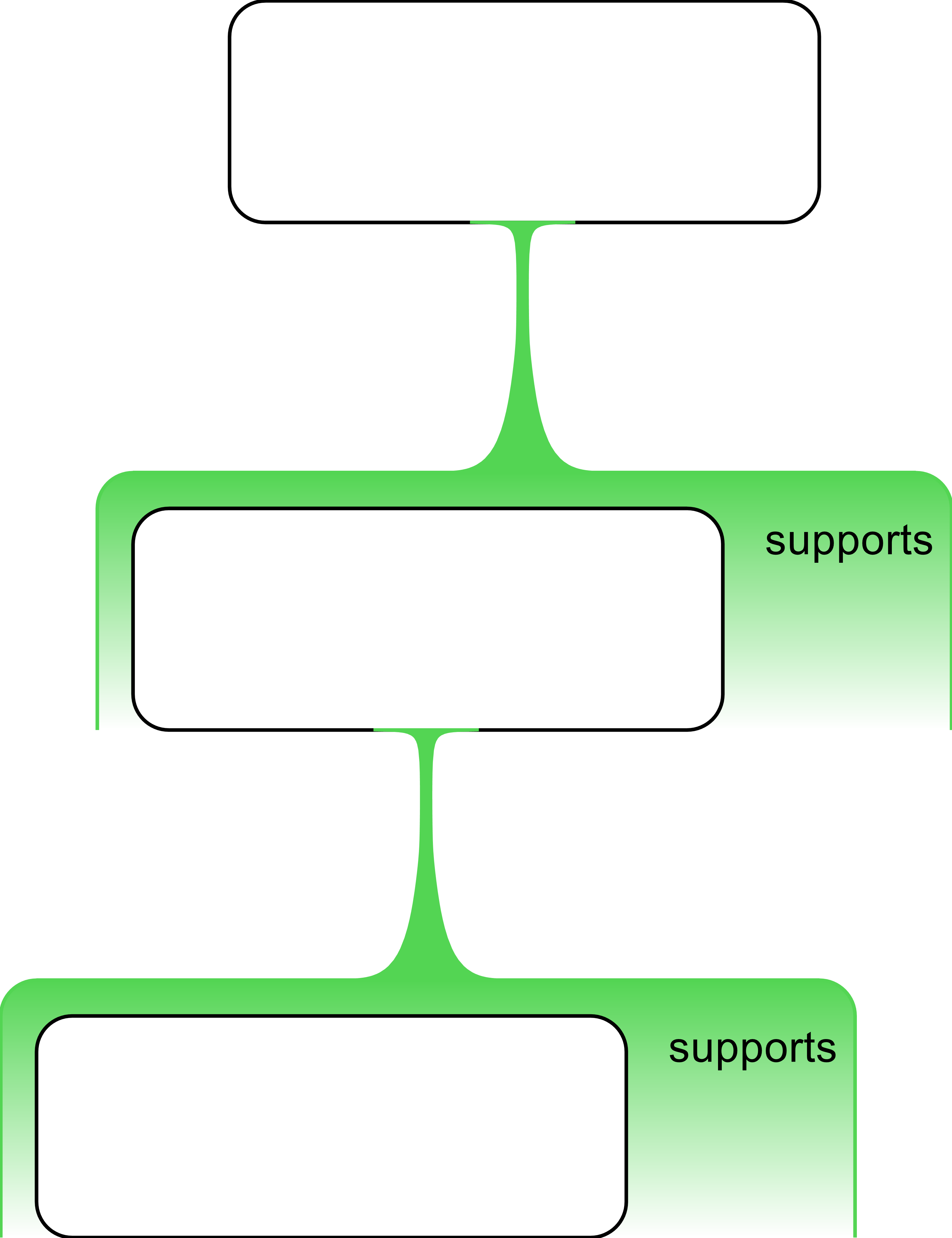

As students advance their understanding of argument mapping, multi-layer arguments can be introduced. These arguments have primary reasons supported by secondary level reasons.

An example is provided below. Here is should be noted that the contention of one argument can become a premise of another argument (naturally, mapping an argument does not imply one agrees with it):

A multi-layer argument

It takes a great deal of practice for students to accurately reconstruct multi-layer arguments from a passage of raw text. Gratuitous assumptions are often made in authentic prose, premises are left out, and connections between premises are contentions are not clear. The job of the argument mapper is to make all connections between reasons and contentions, and between primary and secondary-level reasons very explicit. There is no substitute for a skilful pedagogy that builds student’s skills from achieving competence in analysing and reconstructing simple and complex arguments, eventually to multi-layer arguments.

Expressed as a single multi-level argument this becomes:

Objections

The notion of an objection can be generally explained without difficulty as it mirrors the structure of reasons. Indeed, objections are simply reasons against something, and likewise, come in simple, complex and multi-layer variations.

When discussing objections, it should be made clear to students that objections can be supported by reasons—reasons here provide evidence that suggests an objection is a good one. For example:

Ambiguity

Students should be made aware that very often passages of text are ambiguous. Argument mapping has to deal with such ambiguities. Is the following example a singular claim, or a claim for which a reason is given (an argument)? i.e., is it best rendered as a simple conditional claim?

Or should it be rendered as an argument (a contention with a premise offered in support of it)?:

Such examples are often context-dependent; a function of whether the author is trying to convince the reader of something, or whether they are merely asserting something. Class time should be devoted to looking at passages of text, establishing whether they are arguments or mere assertions and translating them into the argument mapping software.

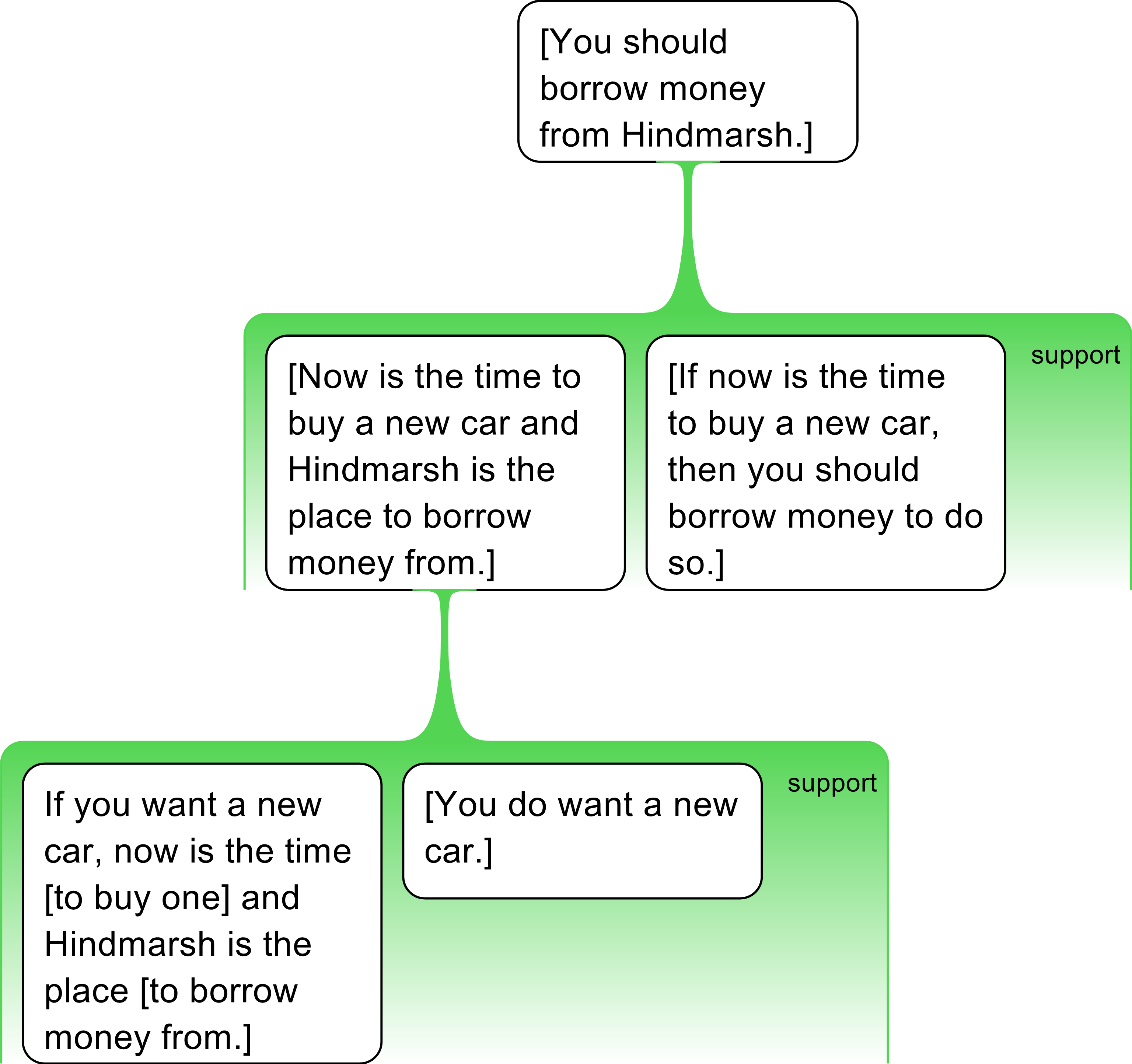

As well as statements that could be arguments, there are also arguments that have implicit inferences that need elucidation. This phenomenon is very common. For example:

- If you want a new car, now is the time and Hindmarsh is the place.

This advertising slogan for a Building Society money-lender is probably best interpreted (charitably) as an argument, not merely a conditional statement. It is trying to convince us of something. Context, and knowledge of the role of money-lenders in society can help interpret it. A moment’s reflection will tell us that the passage is trying to convince us that we should borrow moneyfrom Hindmarsh. Unfortunately for students, this contention is not present in the passage but must be gleaned from it. Indeed, the passage also intimates wewant a new car! What seems like a simple conditional assertion appears to be a subtle argument with an intermediate conclusion and number of assumed premises. A possible interpretation of the argument is represented using the argument mapping software Rationale™ below.

No argument software can assist on its own with the interpretation of difficult passages of text like this, and an instructor’s role is essential (Note that argument mapping convention requires that implicit or hidden claims, when explicated, are expressed in square brackets […].).

Exposure to many different texts, and teaching sensitivity to argument context, can help. For example, the following advertising slogan:

-

The bigger the burger the better the burger, and the burgers are bigger at

[Hungry]

Jack’s.

conceals an implicit conclusion: So/Therefore the burgers are better at[Hungry]Jack’s. Not including the contention renders the passage as a simple assertion rather than what it really is, namely, an argument with an implied contention—and a non-sequitur at that!

Enthymematic arguments (with suppressed claims) are difficult for students, and are commonplace in reasoning. In this example, these premises work together as co-premises to support the (implied) contention. We shall discuss how to deal with these below.

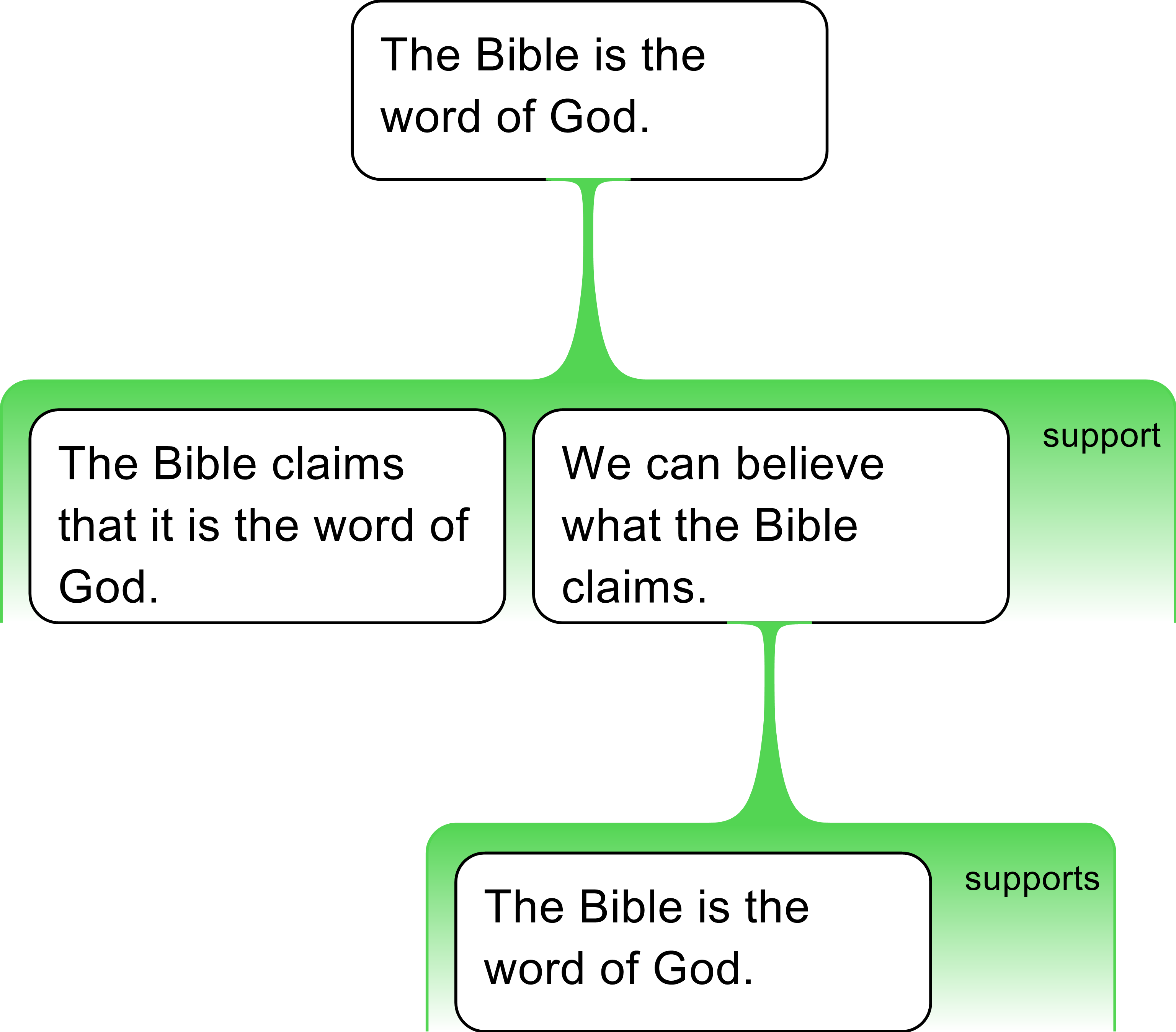

As well as dealing with enthymematic arguments, mapping is also helpful in clearly identifying and exposing instances of circular reasoning—where question-begging supporting reasons are provided, as the following example indicates:

Inference indicators

Early in class instruction it is important to introduce the idea of an inference indicator. There are two types: (a) reason indicators and (b) conclusion indicators. The difference between them is the role they play in an argument. It should be demonstrated how these words and phrases have different grammatical roles too. Reason indicators such as because point to the reason in a grammatical construction; conclusion indicators (like so and therefore) point to the contention. The role they play in sentence construction can be introduced and it can be shown how they can be transposed.

| Conclusion indicator pointing to a conclusion | … can be transposed to a reason indicator pointing to a reason |

| The crops failed [implies] the Sun God is angry. | The Sun God is angry [since] the crops failed. |

| He had a low mark [consequently] he failed. | He failed, [as shown by] his low mark. |

| A strong work ethic [strongly suggests that] one will be successful. | Success in life is [strongly suggested by] one’s work ethic. |

| You want to get a High Distinction [therefore] you should study hard. | You should study hard [because] you want to get a High Distinction. |

Students should learn the different kinds of indicators to help determine what a reason is; and what a conclusion is. They should be given practice in translating passages like these into simply box and arrow diagrams, or—if they are confident—into argument maps. A table showing how the indictors work can be helpful here (examples provided here are not exhaustive).

| Conclusion Indicators | Reason Indicators |

| Implies | Since |

| Therefore | As shown by |

| Hence | For |

| Thus | As |

| So | In view of the fact that |

| Consequently | Because |

| It can be seen that | Seeing that |

| Strongly suggests that | Is strongly suggested by |

At present, CAAM software has a limited range of inference indic

a

tors most

ly

using

because

or the neutral term

supports

exclusively

(i.e., premise X

supports

contention Y

; or X

because

Y

)

.

S

tudents need to be able to translate the many inference indicators used in text into the

blunt categories offered by

CAAM software.

This is one

of its drawbacks. F

uture develo

pments might address this. Given present limitations,

it is important that students understand how to interpret ordinary language arguments replete

in inference indicators of diffe

r

ent

kinds.

Nothing substitutes for class work using passages of text that illuminate the many

examples

of indicator words in use.

Over-interpretation of inference indicators

When students are sufficiently informed about inference indicators, they can be prone to overuse their relevance and see arguments when they are not there. This is something the instructor needs to be wary of as well. Take, for example, the sentence: Sally said she was hungry before, so that is why you can see her eating a sandwich now. This appears to have an inference connector, “so”, but the “so” functions grammatically to connect an explanation to an observation, not as an inference indicator. The passage is not concluding that you can see Sally eating a sandwich. Similarly, Synonyms are good servants but bad masters, therefore select them with care. This is not proffering a contention; it is best interpreted as a subtle piece of advice. Inference indicator words are thus not always indicating an inference (neither is the indictor word thus in that sentence). There is a difference between their use in inference-making and their use in grammatical construction. Again, lots of text-based practice is needed.

Tiers of Reasons/Objections

:

A procedural approach to argument m

apping

We have mentioned that arguments can be represented in terms of tiers of reasons and objections

in the form of multi-layered arg

u

ments

.

It is very easy for students to become overwhelmed by the di

f

ficulty of this task. How is this best taught and what are the things to watch out for?

As always, it is best to start with simple examples and then

attempt

more complex examples. The following example

, the kind of thing to be

found in a ‘Letter to the Editor’

,

provides an instructive case.

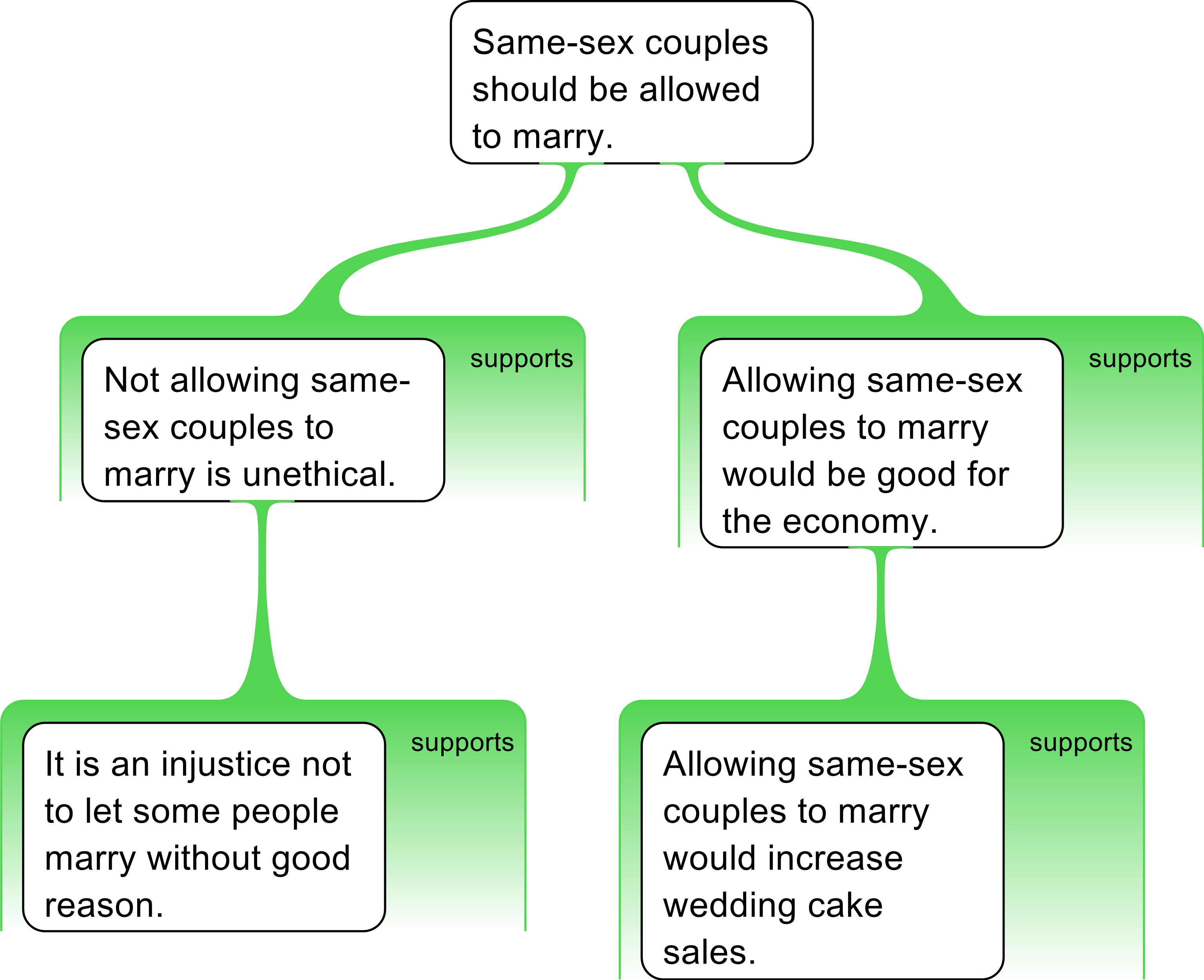

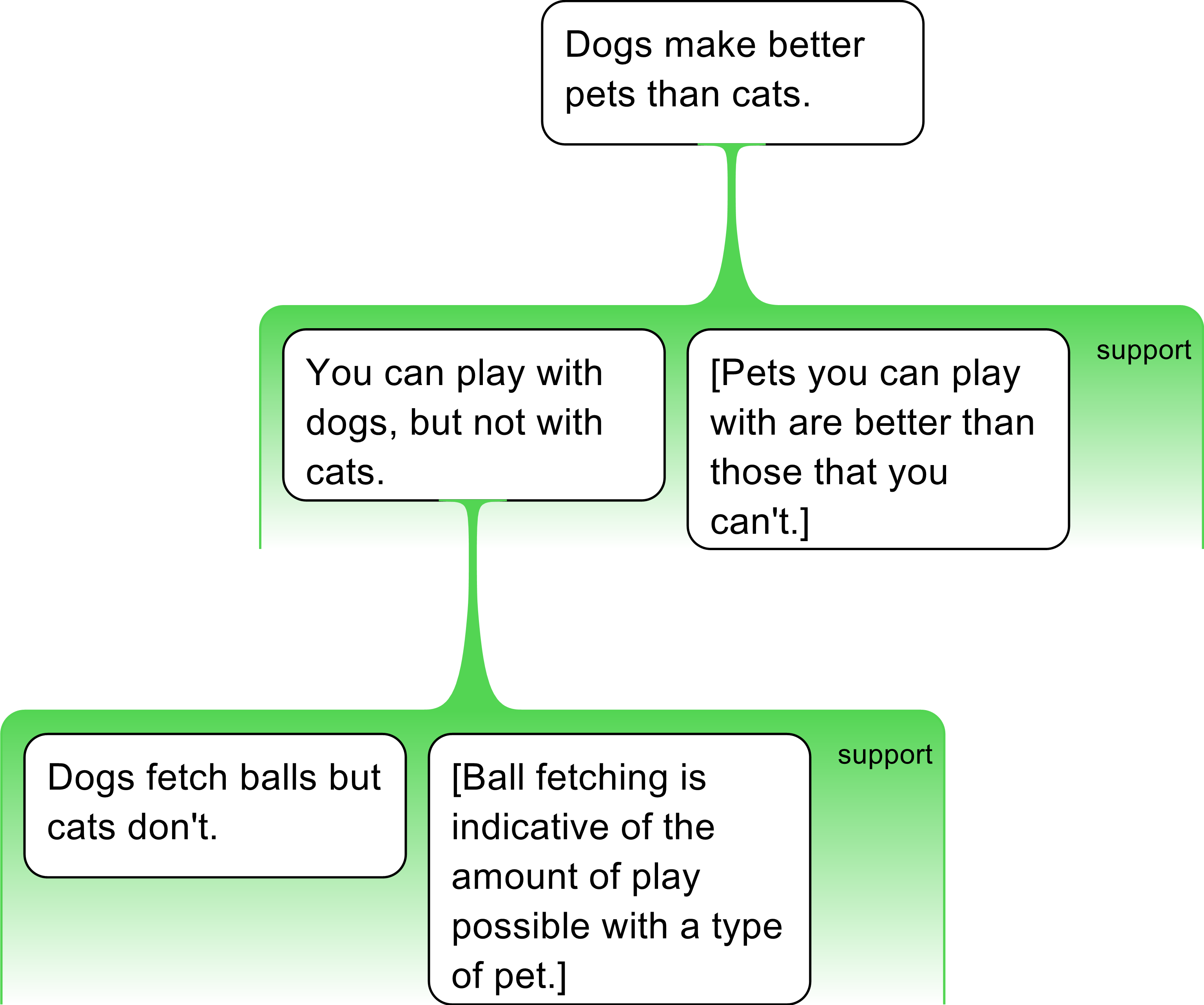

- Dogs fetch balls and cats don’t, so you can play with dogs. I mean, who’d disagree with that? It’s obvious isn’t it? You can’t play with cats, of course. They are too stuck up. Dogs clearly make better pets.

It is clearly an argument. How can one map it to clearly display the reasoning?

To establish this, it is best

to ask students to follow a s

e

ries

of steps. Th

is is

important

as th

ere is a strong tendency for st

u

dents to jump into the task of mapping a passage without

clearly thinking through the text, nor

establishing the connections between the component parts of an argument.

Here is a suggested

step-by-step approach that could be used

with students

to help them understand arguments

. It is a good idea to a

sk student

s

to

follow these steps for any argument under consideration

:

Number the independent claims in any passage of text, ensu

r

ing that each claim is a singular statement or proposition.

A

ssess each claim dispassionately.

I

gnore filler words like “Also”, “however”, or “clearly” which are not germane to the argument.

E

stablish the conclusion

,

which often

needs to be ascertained without the help of inference indicators.

Ask yourself

:

What’s the

point?

Sa

y

Convince me!

T

he contention being argued for

will typ

i

cally emerge naturally

.

Place this

at the top of the map in a conte

n

tion box (

Note:

it is possible to invert argument maps in some sof

t

ware, displa

ying contentions horizontally.)

This step is follow by:

Eliminating the redundant expressions not germane to the argument, and the questions (non-claims), we get the following: <1>Dogs fetch balls and cats don’t, so <2>you can play with dogs. I mean, who’d disagree with that? It’s obvious isn’t it?<3>You can’t play with cats, of course. They are too stuck up.<4>Dogs clearly make better pets.

The claims are as follows:

- Dogs fetch balls and cats don’t

- You can play with dogs

- You can’t play with cats

- Dogs make better pets

Using the What’s the point? test mentioned above, the conclusion reveals itself to be the last claim <4>. This is placed at the top of the map, but how are the reasons supporting it to be arranged? The temptation might be that there are two independent reasons supporting the contention: You can play with dogs and You can’t play with cats.

But this representation of the argument is missing something. W

hat is to be done with

claim

<1>

Dogs fetch balls but cats don’t?

A

t this point a

ttention should be drawn to the inference indicator “so”

that

seems to draw

a conclusion

, i.e., it is not merely functioning gra

m

matically in the sentence

. But this

“so”

is

clearly

not an inference to claim <4>; it appears to be an inference to an intermediate conclusion

that consists of claim <2> and

thus

should thus be represented

in a multi-level argument

like this:

On reflection, it can be seen that that the two supporting reasons <2> and <3> are best rendered as a single claim—an intermediate concl

u

sion

(they are both making a point about “playing”)

—and the claim about

“

fetching

”

can be seen

as reasoned support for this

. This ca

p

tures the intended use of the connector word “so” linking <1> to <2>. There is thus another rule to consider:

The resulting argument map provides a clear

example of serial re

a

soning

that accurately represents the

case being made:

In the case of more complex arguments additional principles need to

be

followed.

The principle of abstraction

A

very useful guideline for

argument mapping is the

principle

of a

b

straction

.

In many cases, t

he higher the claim in a multi-layered

a

r

gument the greater the degree of abstraction; or to put it differently,

the lower the claim the more specific it

should

be. In the above exa

m

ple, “playing” is more abstract than “

fetching balls

”

, and

both claims are less abstract than “better

pet

”. They

provide serial support for each

other

.

Students should be guided in how to apply this

principle,

as without this, maps can become a jumble of disorganized claims with no clear

hierarchical structure.

Once again, this requires practice and students should be given

a number of

exercises where they are required to rank claims in terms of their degree of abstraction.

To our series of rules we can add

the following

:

The principle of level consistency

Complex

arguments have both a vertical and a horizontal axis.

A

r

guments can be multi-layered along the vertical axis

(as we have just seen)

, but

premises

are

present

along a horizontal axis as well. I

n

sofar as many premises can be brought to bear in an argument it is i

m

portant to stress another principle,

the

principle of level consistency.

W

ithin each

horizontal

level, reasons or objections should be appro

x

imately

of equal weighting in terms of their abstraction or generality.

In the following argument t

his rule is not adhered to

and is cons

e

quently hard to interpret:

This argument is improved

by subordinating lower-level claims to

a more general claims

at the middle-level, and ensuring level consiste

n

cy at the lower level,

as follows:

We can thus add another

guideline

:

Missing Premises

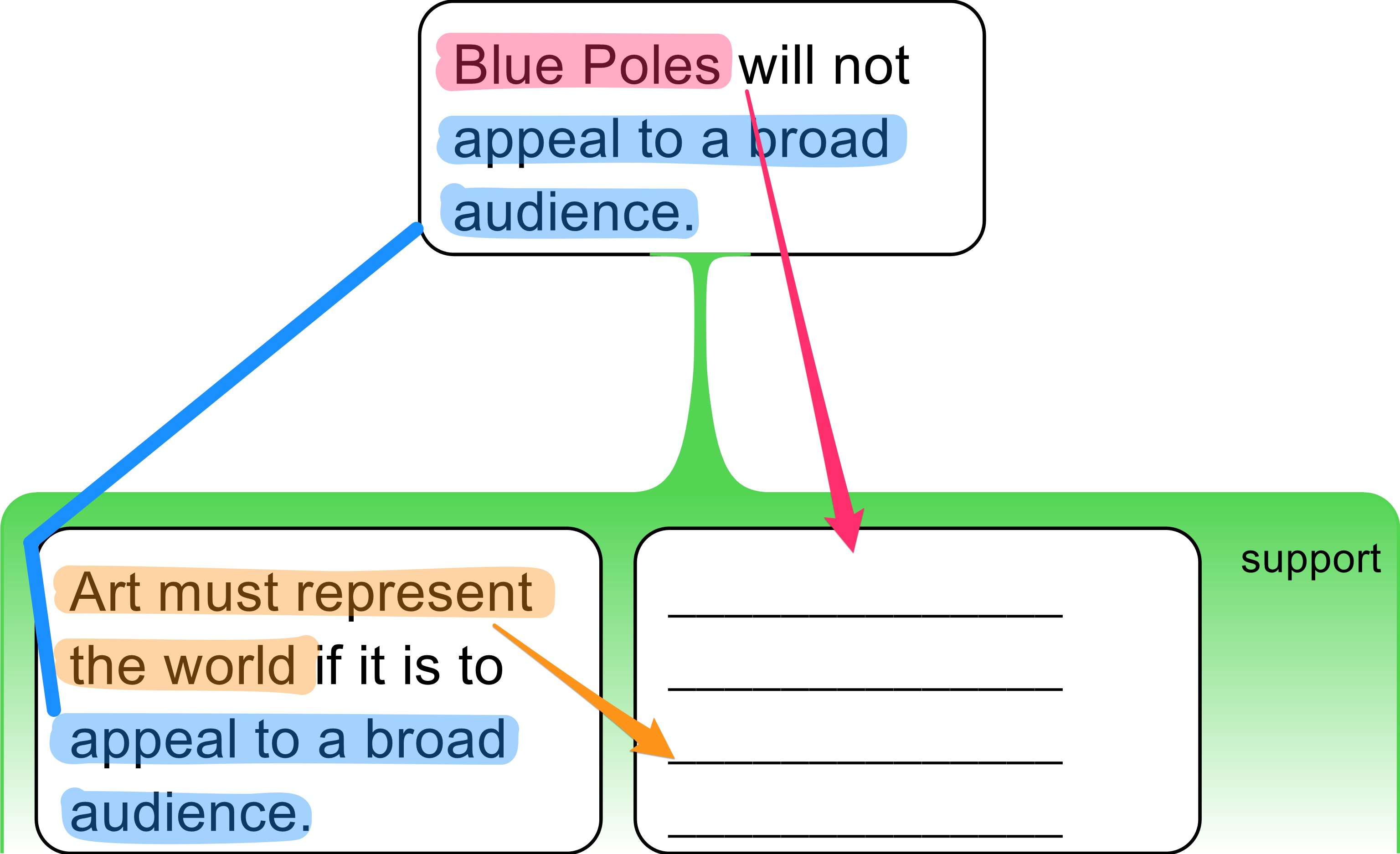

Teaching students how to look out for missing premises is complex, but there are strategies that can help. It is difficult because reasoning is often replete in missing premises. Indeed, it is veryrarethat all premises are made explicit in reasoning. This is due to the implicit reliance of speakers or writers on the background beliefs assumed to be shared in any argumentative exchange. Here is a simple example.

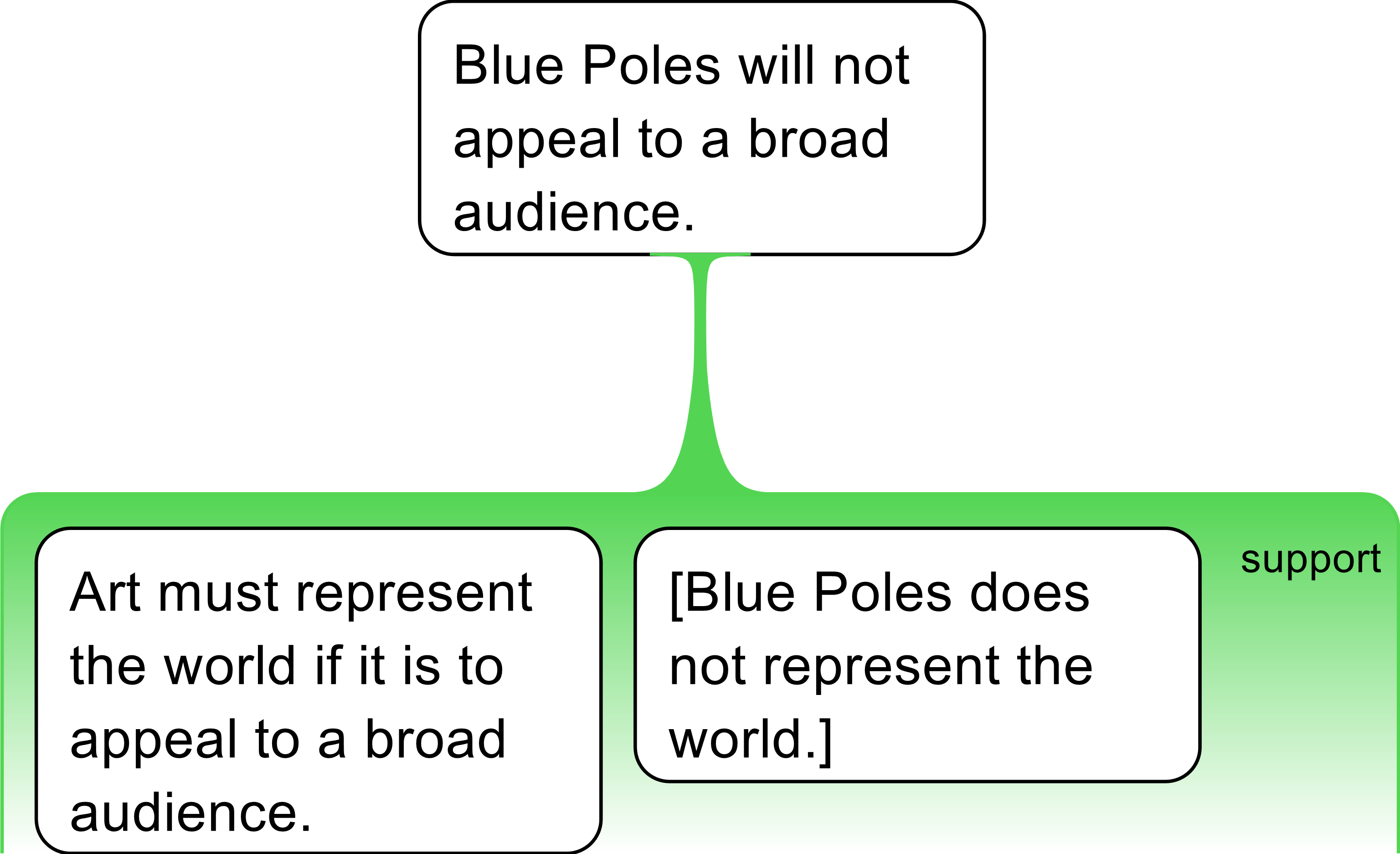

-

Art must represent the world if it is to appeal to a broad audience

for generations to come

.

So t

hat’s why

Blue Poles

will

not appeal to a broad audience

.

In a normal human exchange, this would be a perfectly clear expression of a (rather dated) view about the painting Blue Poles. It is also an argument. We are giving a reason for a conclusion, as indicated by the words “so that’s why”. However, when teaching argument mapping it is an example of an argument with a missing premise; a premise that needs to be exposed, and made clear. What, precisely, is being argued?

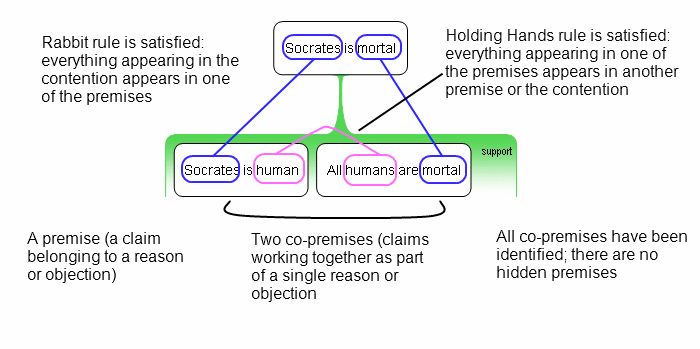

In this case, it is easy to see what missing is. It is the assumption that Blue Poles does not represent the world. Exposing this missing premise allows it to be evaluated, confirmed or rejected. In this example, the missing premise can stated quite easily; in simple passages, this is often the case. But for more complex reasoning a series of steps need to be followed to ensure all missing premises are catered for. Fortunately, there is a very simple way to establish missing premises. This is done by applying two rules: the Rabbit Rule and the Holding Hands Rule. These rules are outlined in more detail in online tutorials available with the software Rationale™.

Assumptions and how to find them using the Rabbit Rule and Holding Hands Rule

The Rabbit Rule is applied (vertically) to the inferential link between conclusion and the premises. This rule states that no conclusion should come out of thin air. (No rabbits out of hats!) The conclusion term(s) have to be present in the terms of the premises of an argument for it to appear in the conclusion. In the argument under consideration we can see that “Blue Poles” appears in the conclusion but does not appear in the available premise. We therefore know that Blue Poles must be supplied to the missing premise.

The Holding Hands Rule is applied horizontally between premises to any remaining terms after the Rabbit Rule has been applied (that is, if a term is not already supplied by means of the Rabbit Rule). The remaining terms must “hold hands” with another premise. No term can appear in one premise alone—there is always a companion term “holding hands”. In this example, we can see that “represent the world” appears in the stated premise, so it must be present in the missing premise. As the argument is negating something about Blue Poles, we similarly apply a corresponding negation to the terms of the missing premise.

The argument can be expressed as follows:

We can add the following to our list of procedural rules to establish missing premises:

The following example of a famous deductively valid argument in Philosophy demonstrates how both the Rabbit Rule and the Holding Hands Rule are satisfied. It also demonstrates an example of co-premises in action:It may not have escaped notice that the two claims that support the above contention are jointly necessary for the conclusion to follow. Strictly speaking they are not two independent reasons supporting the conclusion, but are co-premises that jointing support the conclusion. This raises the important issue of co-premises or “linked” premises. This is another crucial methodological principle that students find difficult.

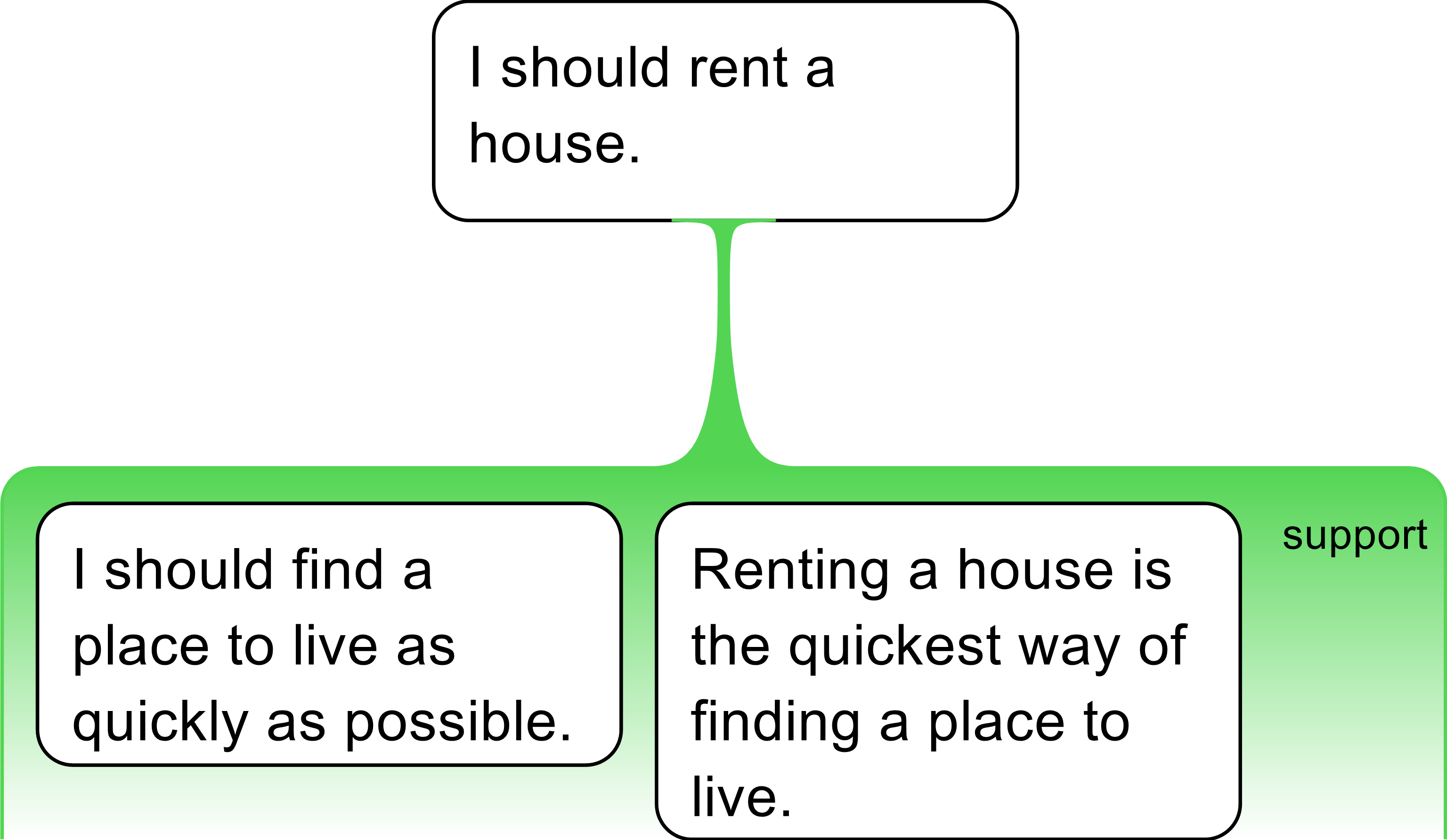

A co-premise is

when

two or

more premises

are jointly

necessary

for the truth of the conclusion. Co-premises are often enthy

me

matic

and s

ome

times a co-premise is trivial. For example, a

person who reasons that they should rent a house because they

should find a place to live

as quickly as possible

,

tacitly

assumes

that renting a house is

quickest way of find

ing

a place to live

.

Such assumed claims are often tacit in arguments in both writing and speech, and are often so trivial they do not need to be stated.However, they are an important feature of arguments. Indeed, every argument has at least two of them. In CAAM this is often mentioned as “The Golden Rule”: every argument has at least two co-premises. In the following example, we have extended the previous argument discussed by the addition of enthymematic co-premises.

While ubiquitous in reason

ing, co-premises are not always

unco

n

troversial

.

Often, co-premises

conceal hidden assumptions that are false or misleading.

This is why it is good argument mapping practice to expose them.

For example, it need not be accepted

(without ev

i

dence—

or even intuitively)

that

pets

that you can play with make be

t

ter pets

than those you can’t

[play with]

(elderly people

, the infirm

or

disabled

, for example,

like more docile pets).

Being able to e

x

pose hidden assumption

clearly

for the purpose of critiquing them

is a m

a

jor advantage of argument mapping.

Argu

ment mapping software makes identification and representation of hidden claims

easier by using

color

conventions and shading; however, this does not help st

u

dents deciding how to determine how to locate a co

-premise in a pa

s

sage of text. Clear i

nstruction and LAMP is needed.

Probably the best

way to approach co-premises

in the classroom

is to begin by discus

s

in

g the differences between complex

reasoning and linked reasoning.

Co-p

remises (Linke

d r

easoning)

S

tudents find

the distinction between linked

reasoning

(dependent premises) and complex

reasoning (independent

premises

) hard to grasp.

It

is best taught by

showing students a number of

simple multi-premise a

rguments

and asking them to classify

examples of

complex

and linked reasoning

.

In the following

example,

it is

fairly

easy to see that the supporting premises are independent and not necessary for each other

.

Plausibly, neither premise could be true; or both could, or one coul

d be true and the other false. If either premise was true t

he conclusion could sensibly follow in either case. The conclusion could follow even if one of the claims was

missing.

In other examples, co-premises are neede

d

as the claims are

not ind

e

pendent of each other and are

examples of linked reasoning

. For i

n

stance

:

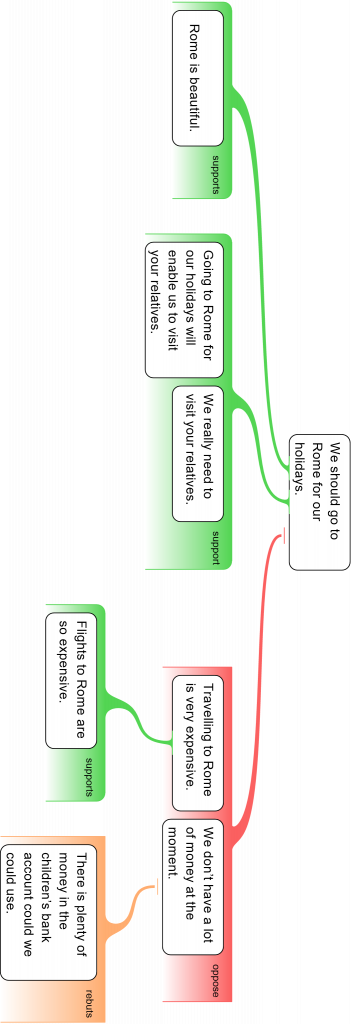

- We should go to Rome for our holidays. Rome is beautiful. Also, it will enable us to visit your relatives and this is something really need to do.

The passage complete with numbered claims would look like this:

- <1 We should go to Rome for our holidays>. <2 Rome is beautiful.> Also, <3 It will enable us to visit your relatives>, and <4 this is something really need to do>.

How can one teach students w

hich premises are linked and which are independent?

To

our set of suggested procedural rules

discu

ssed earlier, we can add another

step:

In the example above the claim Rome is beautiful is an independent reason (it does not depend on visiting relatives) and the contention We should go to Rome for our holidays can be supported by it. The contention can follow from Rome being beautiful regardless of the other claims provided. However, the claims about visiting the relatives appear to be linked. The claim: This is something [Visiting your relatives] we really need to do will not alone support the conclusion without including the claim It [Visiting Rome] will enable us to visit your relatives. Note however, this relationship is not symmetrical. Premise <3> can support the contention without premise <4>. However, <4> can’t without <3>. If one premise can’t support a conclusion without another premise, they are said to be “linked”. In convergent (or divergent) reasoning, none of the claims are dependent on any other claim; either one of the claims might support the conclusion alone. By contrast, in linked reasoning, the claims are not independent; they are necessary for each other for the conclusion to follow.

With <2> as an independent premise, and

<3> and <4> being

linked premises,

the map would appear as follows:

A

useful feature of argument mapping is the capacity to display linked premises

in an intuitive visual way

.

Like other software, t

he software

Rationale™

(used here)

uses

the colo

r

green

for reasons

and

the colo

r

red for objections

(

the colo

r orange

is used exclusiv

e

ly

for rebuttals

, i.e., objections to objections

)

. Co-premises are ind

i

cated by

an umbrella

shading that

fades to white

. This is a subtle

visual

indic

a

tion

that no argument is ever complete and more premises could p

o

tentially be added.

O

bjections too can be linked as co-premises as the

following exte

n

sion

to the argument indicate.

We have added a rebuttal against an objection

(in orange)

to demonstrate their use.

-

On the other

hand <5

>

travelling to Rome is very expensive

,>

primarily because <6

>

flights are so expensive>. And <7

>

we don’t have a

lot

of money at the moment>.

But then again, <there is

plenty of

money in the children’s bank account

we

could

use>.

We have laid out the complete map of the argument on page 169.

Note here that the claim that Travelling to Rome is expensive could well object to the conclusion alone, but premise could not (without premise ). The premises under consideration must independently support the conclusion to stand as independent reasons. If this is not the case, the premises are said to be linked.

A brief history of argument mapping

Argument mapping can be traced to the work of Richard

Whately

in his

Elements of Logic

(1834/1826)

but his notation was not widely adopted. In the early twentieth century, John Henry

Wigmore

mapped legal reasoning using numbers to indicate premises

(Wigmore, 1913; Wigmore, 1931)

. Monroe Beardsley developed this, and it became

standard model of an argument map

(Beardsley, 1950)

. On this a

p

proach, premises are numbered, a legend is provided to the claims identified by the numbers, and

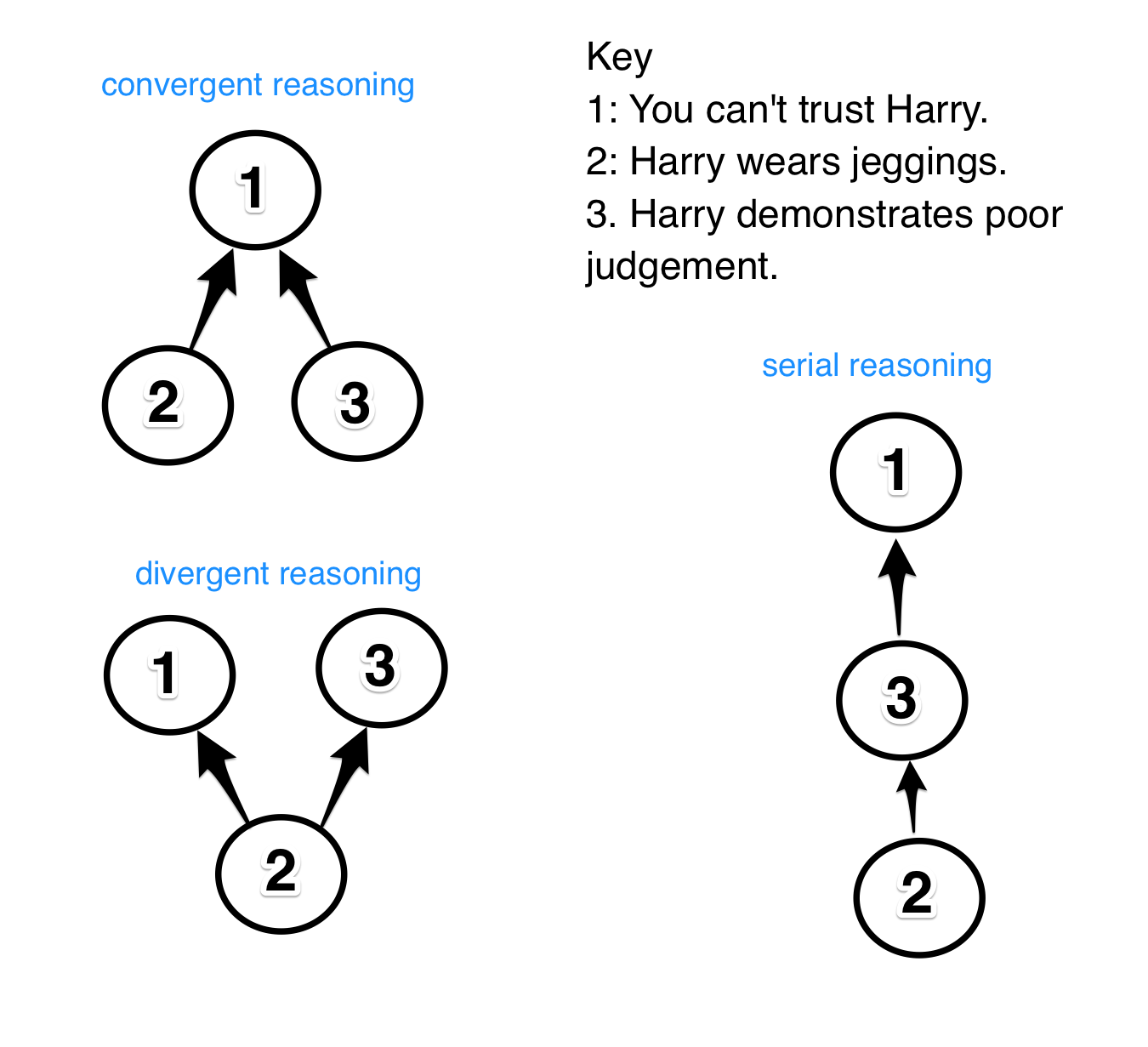

serial, divergent and convergent

re

a

soning can be clearly represented. An example of each of these forms of reasoning using the standard model is provided below.

This model is still widely used and is advantageous in contexts where students are required to produce argument maps without access to software (e.g., in paper-based logic and reasoning exams under timed conditions).

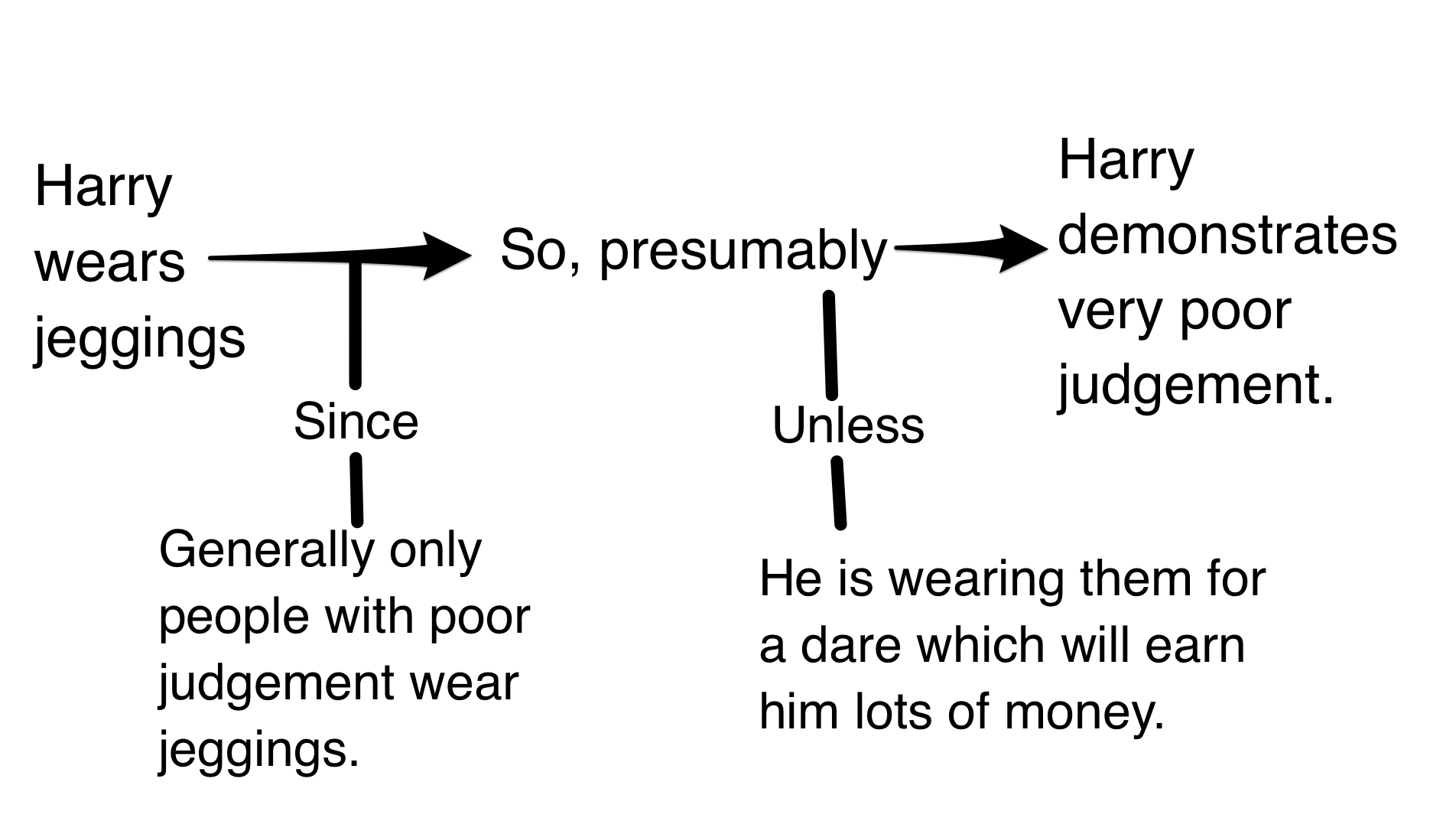

In 1958, Stephen Toulmin devised another model of an argument map that included the notion of a “warrant” (which licenses the inference from the reasons, which he called “data”, to the claim), “backing” (which provides the authority for the warrant), modal qualifiers (such as “probably”), and “rebuttals” (which mention conditions restricting the inference) (Toulmin, 1958).

An example of a Toulmin map is provided below.

In 1973, Stephen

L. Thomas refined Beardsley’s approach

(Thomas, 1997/1973)

. Thomas included in his approach the important notion of “linked” arguments where two or more premises work together to support a conclusion (the distinction between dependent and ind

e

pendent premises having being described earlier). This innovation made it feasible for arguments to include “hidden” premises. He is also said to have introduced the terms “argument diagram”, “basic” (or “simple”) reasons, i.e., those not supported by other reasons (as distinct from “complex” reasons). He also made the distinction b

e

tween “intermediate” conclusions (a conclusion reached before a final conclusion) and a “final” conclusion (not used to support another conclusion). Thomas also suggested including objections as reasons

against

a proposition, and that these too should be included in arg

u

ment maps.

In 1976

, Michael

Scriven

proposed a procedure for mapping that could be recommended to students

(Scriven, 1976)

. This involved a number of steps:

(

1) writing out the statements in an argument;

(

2) clarifying their meaning;

(

3) listing the statements, including any hi

d

den claims; and

(

4) using numbers for premises along the lines of the Beardsley-Thomas model. In the case of hidden assumptions,

Scriven’s

notation used an alphabetical letter to distinguish hidden assumptions from explicit reasons.

Scriven

also

emphasized

the i

m

portance of a rebuttal in argument mapping, a notion identified earlier by Thomas.

In the 1990s a number of innovations occurred. Robert Horn

helped

popularize the notion of an argument map by producing idiosyncratic,

large-format argument diagrams on key issues in philosophy such as “Can Computers Think?”

(Horn, 1999; Horn, 2003)

.

These maps did not adopt either the standard model or

Toulmin

-style notation for mapping arguments, but did use arrows and pictures to make the co

n

tent clear, making it obvious for the first time that argument maps could be visually interesting as well as informative. These were di

s

tributed widely and used in class teaching. In addition, computer software programs began to be developed. This was important, as dedicated argument mapping software allowed premises to be co

m

posed, edited and placed within an argument map, as distinct from a legend alongside the map.

Argument mapping software

Once dedicated computer software was introduced, the standard mo

d

el of numbered premises became outdated in all contexts outside its use in examinations. Several iterations of mapping software were d

e

veloped in Australia and the U

.

S

.A.

with increasingly greater levels of sophistication. Tim van

Gelder

developed

Rationale™

and

bC

i

sive

™

,

the former designed as a basic argument mapping software, the latter designed for business decision-making applications

(van Gelder, 2007, 2013)

.

Both were later purchased by Dutch company

Kritisch

Denken

BV

.

A variety of argument mapping packages are now available, including Araucaria, Compendium,Logos, Argunet, Theseus, Convince Me,LARGO, Athena, Carneadesand SEAS. These range from single-user software such as Rationale™, Convince Meand Athena; to small group software such as Digalo, QuestMap, Compendium, Belvedere, and AcademicTalk; to collaborative online debating tools for argumentation such as Debategraphand Collaboratorium. Enhancements to argument mapping software proceed apace. For example, there are moves to introduce a Bayesian network model to Rationale™to cater for probabilistic reasoning.

Rationale™

or

bCisive

are perhaps the easiest programs to use for teaching argument mapping, but they require a subscription.

E

xcellent free alternative

s

i

nclude

the

Argumen

t

Visualization

mode in

the online

MindMup

:

https://www.mindmup.com/tutorials/argument-visualization.html

, and the cross-platform desktop package

iLogos

http://www.phil.cmu.edu/projects/argument_mapping/

Argument mapping class room examples

There are a number of free argument resources available online.

- The designers of Rationale™ made tutorials to be used with their software. https://www.rationaleonline.com/docs/en/tutorials#tvy5fw

- Simon Cullen, who helped design the MindMup argument visualisation function, has posted some of the activities he uses for teaching philosophical arguments using argument maps. http://www.philmaps.com

- Ashley Barnett, who has written lots of questions for argument mapping courses for students and intelligence analysts has posted his teaching material on http://www.ergoshmergo.com

Conclusion

In this paper we have covered some of the basic concepts and considerations that teachers need to be aware of when using CAAM in the classroom. A set of procedural steps was suggested that is recommended for use with students. Understanding claims and arguments and how they are structured is only the start. Students should also be aware of how to interpret inference indicators, construct and analyse simple, complex and multi-layer arguments, and be able to integrate objections and rebuttals. They should be wary of misusing inference indicators, confusing reasons with evidence for reasons, and misinterpreting independent reasons for co-premises. There is much more we could have discussed. We have not touched on the use of inference objections (in contrast to premise objections). We have not mentioned argument webs or chains of reasoning, nor have we discussed in detail the appropriate ways to integrate evidence into an argument. However, it should be clear from this brief outline how CAAM can assist students in disentangling arguments in everyday prose—replete, as it often is, with non-sequiturs, repetition, irrelevancies, unstated conclusions, and other infelicities.

References

Beardsley, M. C. (1950). Practical logic. New York: Prentice-Hall.

Davies, M. (2009). Computer-assisted argument mapping: a rationale approach. Higher Education, 58, 799-820. Higher Education, 58(6), 799-820.

Davies, M. (2011). Mind Mapping, Concept Mapping, Argument Mapping: What are the Differences and Do they Matter? Higher Education, 62(3), 279-301.

Harrell, M. (2008). No Computer program required: Even pencil-and-Paper argument mapping improves critical-thinking skills. Teaching Philosophy, 31(4), 351-374.

Horn, R. (1999). Can Computers Think? : Macrovu.

Horn, R. E. (2003). Infrastructure for Navigating Interdisciplinary Debates: Critical Decisions for Representing Argumentation. In P. A. Kirschner, S. J. B. Shum, & C. S. Carr (Eds.), Visualizing argumentation: Software tools for collaborative and educational sense-making. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Rider, Y., & Thomason, N. (2008). Cognitive and Pedagogical Benefits of Argument Mapping: L.A.M.P. Guides the Way to Better Thinking. In A. Okada, S. Buckingham Shum, & T. Sherborne (Eds.), Knowledge Cartography: Software Tools and Mapping Techniques (pp. 113-130): Springer.

Scriven, M. (1976). Reasoning. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Thomas, S. N. (1997/1973). Practical reasoning in natural language (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Toulmin, S. E. (1958). The uses of argument (first ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

van Gelder, T. (2007). The Rationale for Rationale™. Law, Probability and Risk, 6, 23-42.

van Gelder, T. (2013). Rationale 2.0.10. Retrieved from http://rationale.austhink.com/download

van Gelder, T. J. (2015). Using argument mapping to improve critical thinking skills. In M. Davies & R. Barnett (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Thinking in Higher Education (pp. 183-192). New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Whately, R. (1834/1826). Elements of logic: comprising the substance of the article in the Encyclopædia metropolitana: with additions, &c. (5th ed.). London: B. Fellowes.

Wigmore, J. (1913). The Problem of Proof. Illinois Law Review, 8, 77.

Wigmore, J. (1931). The Science of Judicial Proof as Given by Logic, Psychology and General Experience and Illustrated in Judicial Trials (2 ed. Vol. Little, Brown and Co. ): Boston.

- © Martin Davies, Ashley Barnett, & Tim van Gelder ↵

- The colored versions of the argument maps in this chapter are available only in the open-access Ebook edition of this book at: https://windsor.scholarsportal.info/omp/index.php/wsia/catalog↵

- https://www.rationaleonline.com/docs/en/tutorials#tvy5fw). ↵

<!– pb_fixme –>

<!– pb_fixme –>