Narrative

Here is perhaps a surprising fact: cinema was not invented to tell stories. That it came to do so on its way to become the 20th century’s dominant entertainment form is not so much a historical accident as a consequence of its development into an industrialized art. But storytelling is not “natural” to the medium, so in order that the moving image could be pressed into service for story, its practitioners had to develop conventions that would allow any spectator to follow its narrative action. This chapter outlines terminology related to film narrative.

DEFINING NARRATIVE

What is a narrative? A simple answer would be that a narrative is a series of events that happen, but this is insufficient. The events that make up a narrative have to be related to each other by more than just chronology. When describing their writing process, South Park (Comedy Central, US, 1997- ) creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone succinctly capture the difference between a chronological series of events and a narrative. They explain that between each beat (a basic unit of narrative action) of a story, a writer must avoid thinking “and then.” Instead, a writer should either place “therefore” or “but” between each beat. So, it’s not “this happens, and then that happens,” but “this happens, therefore that happens” or “this happens, but that happens.” What this basic writing hack intuitively grasps is that narrative is a series of events linked to each other through causality. Causality specifies a relation of cause and effect. One narrative beat causes another, which is its effect and which in turn acts as a cause for the next narrative beat.

The most common type of causality in film narrative relates to character – chiefly, either the protagonist (the fiction’s main character who moves the narrative action forward) or the antagonist (the fiction’s principal character whose aims oppose the aims of the protagonist). Narrative films establish and develop the psychological interiority of characters to motivate narrative events. The desires, wants, or goals of a character are what establish the causal links between events, especially as they enter into conflict with the desires, wants, or goals of another character or with a set of material circumstances that delay or prevent their realization. Establishing the psychological interiority of a character in a film is not as straightforward as doing the same for a character in a novel. Novelistic description can easily access a character’s internal thoughts, but because a film records the external actions or behaviors of a character, it requires additional formal strategies to suggest what a character is thinking or feeling. Dialogue is the most obvious strategy. Sometimes film characters just say what they want. Often however, viewers must infer a character’s motivations from the set of visual cues provided by the film. That viewers can disagree about these motivations is one cause of differing interpretations of the same film.

THE THREE-ACT STRUCTURE

The standard format for organizing a film narrative is the three-act structure, though film scholars consider much of contemporary mainstream filmmaking to now follow a four-act structure.[1] The first act comprises the film’s exposition. Exposition establishes the diegesis (the world in which the story takes place), introduces characters and their relationships to each other, and reveals the primary aims or goals that will drive the story. The second act introduces the central conflict of the story (whatever stands in the way of the protagonists achieving their aims) and presents complicating action (for example, unintended consequences, betrayals of trust, the revelation of new information, etc.) that delays the realization of the characters’ goals. The second act culminates in a narrative climax, indicating the height of narrative action where “height” does not mean “a lot of stuff happens” but where the intensity of the conflict is at its maximum and the resolution of aims appears furthest from its possible realization. Following the climax, the third act carries out the resolution of the conflict, which entails either the successful achievement of the characters’ goals or the dramatic failure to achieve them. Classically, the resolution of a narrative will usher in a new state of affairs (for example, the marriage of a couple, the solving of a murder, the defeat of a villain, etc.) in the diegesis.

The four-act structure of much contemporary film only entails a modification to the second act of the standard three-act structure. In a three-act structure, this second act of complicating action is typically twice as long as the acts that bookend it. A four-act structure introduces an additional and distinctive turning point within this second act, resulting in four acts of roughly equal length.

Segmenting a Film: Spider-Man: Homecoming

Discussions of three-act structures versus four-act structures are the stuff of screenwriting manuals, but learning how to segment a film narrative can be useful for film analysis, since being able to identify narrative conflict and a film’s turning points clarifies what is meaningful about a particular story. Let’s look at a recent mainstream film as an example: Spider-Man: Homecoming (Jon Watts, US, 2017). As the second film in this iteration of the franchise, Homecoming follows the origin story of Peter Parker’s transformation into a superhero after being bitten by a radioactive spider. As the film centers on a teenage superhero, its central conflict concerns the hero’s attempt to balance his private life as Peter (facing the social pressures of high school) and his public life as Spider-Man (wanting to be a full-fledged member of the Avengers).

Act One

The first act of the film (the exposition or set-up) introduces the causal lines of action that the narrative will have to resolve by its conclusion. There are three main causal lines in Homecoming: Peter’s (Tom Holland) crush on Liz (the romance plot), Spider-Man’s desire to take on more responsibility as an Avenger (the hero plot), and the confrontation with Adrian Toomes (Michael Keaton), an arms dealer trafficking in weapons made from alien technology (the villain plot). The latter plotline is introduced in a prologue that efficiently establishes the villain’s origin story: facing the shuttering of his salvage business, Toomes turns to illegal arms trafficking to continue to provide for his family. Once established, this plotline takes a secondary position to the other two, which are the focus of this first act. The romance plot encompasses Peter’s life as a high school student. He is a member of the Academic Decathlon team, his friend Ned (Jacob Batalon) discovers his secret identity, and he tries to exploit “knowing Spider-Man” through a Stark Industries internship as a means to impress Liz (Laura Harrier) and his classmates. In the hero plot, Spider-Man feels like he has no purpose. Having just assisted on an Avengers mission, he finds the local problems in his Queens neighborhood too minor for his abilities, but Stark, as surrogate father figure, is distant and non-responsive.

Act Two

The second act (the complicating action) begins when the three plot lines no longer run parallel to each other but come into direct conflict. Spider-Man discovers a promising lead to the source of the illegal weapons, and tracking down that source will provide the Avengers-level mission he desires, allowing him to prove himself to be ready to be considered more than just a teenaged kid, undervalued by Stark. This convergence of the hero plot and the villain plot, moreover, complicates the romance plot. Peter had planned to appear as Spider-Man at a high school party (to spend time with Liz, to prove something to Flash) but a distant explosion calls him away. This dynamic will be familiar to viewers of any Spider-Man films, since his responsibilities as the superhero comes at the expense of his wants in his private life.

The second act comprises a long series of narrative events that show Peter/Spider-Man’s efforts to resolve the three plotlines (get the girl, defeat the villain, be an Avenger), but he finds himself foiled each time as progress in one often impedes one of the others. Rather than recounting the entire second act, which encompasses around 90 minutes of screen time, let’s take one example. Peter rejoins the Academic Decathlon team after quitting his extracurriculars in order to be Spider-Man more often. The team travels to Washington D.C. for a competition, allowing Peter to spend more time with Liz and run a side mission tracking the illegal weapons. The night of the mission, he is invited by Liz to go swimming, but he has to turn her down (impeding the romance plot) to stop a heist (advancing the converged hero/villain plot). Though he prevents the theft, Spider-Man gets trapped in a containment facility, causing him to miss the competition. Moreover, he has entrusted Ned with a stone of extraterrestrial origin, which becomes explosive when irradiated. The stone detonates in a Washington Monument elevator, forcing Peter to save his friends. He acts heroically, but it was his own irresponsibility that endangered them.

If we wanted to segment Homecoming into four acts rather than three by splitting the second act into two, what event in the plot would constitute the dividing line? It would be the action sequence on the Staten Island Ferry (Figure 1), when Spider-Man attempts to stop an arms deal but loses control of the situation, causing a weapon to sever the ferry in half, threatening the lives of all its passengers and requiring Stark/Iron Man to intervene in the rescue. Why is this event a turning point? How does it function as a further complication in the relation between the film’s three major plot lines?

The first half of the second act is structured by the repeated interference of his role as Spider-Man with his goals as Peter. This event, though, is a dramatic failure for Spider-Man (the villains escape, innocent lives are endangered), as he takes on more responsibility than he is equipped to handle. The second half of the second act, therefore, has Peter become only Peter again. Stark confiscates his suit, ending the “Stark internship,” and Peter can pursue high school things without the interference of his superhero persona. Not for long, however. Having suspended the hero plot line, the romance plot and the villain plot now dramatically converge. Peter asks Liz to prom, but discovers that the villain he has been pursuing is her father! Her father likewise figures out almost immediately after that that Peter is Spider-Man. Their secret identities are both revealed, throwing the romance plot and the villain plot into opposition. Indeed, Peter is offered a choice: forget what he knows and just be a regular high school student again, or pursue the villain at the likely cost of his romance with Liz.

Act Three

Homecoming’s final third act (or fourth, depending on the segmentation) begins, perhaps unexpectedly, not when he makes this choice (to pursue the villain). We see him do so, telling Liz that he has to abandon her at the prom for a reason he cannot disclose. But this action only pertains to the romance plot. Peter will sacrifice what he desires in his private life for his greater responsibilities as Spider-Man. The conflict between the hero plot and the villain plot, however, remains unresolved. Peter cannot just decide to be Spider-Man again. The hero plot was based on Peter’s desire to be recognized as an Avengers-level superhero, and the complicating action that resulted from this frustrated desire is that Peter sought this aim prematurely, before he was ready for what that responsibility entailed. Peter thinks his identity as Spider-Man is what makes him worth something (“I’m nothing without this suit”), but Stark reprimands him that he has to prove himself capable of wielding the suit’s power (“If you’re nothing without this suit, then you shouldn’t have it”). Therefore, the climax arrives only when the intensity of this conflict reaches its high point. The villain brings down an entire warehouse on Spider-Man’s head, burying him in rubble. Pulling himself from the debris, Peter encounters his own reflection, half Peter and half Spider-Man (Figure 2). Is he worthy of wearing the suit? Does he believe himself to be? Peter’s internalized conviction that he is finally ready to be a superhero, with all that entails, sets off the film into its final act, when we discover how all of these plot lines will conclude. The terms are now clear and the stakes are now set. All that remains is to see how it ends.

So how does it? Spider-Man pursues the villain in an extended action sequence. He offers the villain a parallel choice to the one he had to make: renounce the weapons trafficking and return to being just a father to Liz. But the father chooses his villainous alter ego, his ambition winning out over his fidelity to his family. The villain is then defeated. The other plot lines fall into place. Having proved himself capable, Stark returns Spider-Man’s suit to Peter and arranges to announce him as an Avenger. However, Peter has learned what the villain did not. Though he previously wanted more than his simple high school life, in a rush to take on the adult responsibilities of a superhero, now he can see the value of what he had too easily dismissed. He will make the opposite choice to the villain, humbly sacrificing his previous ambition.

This example demonstrates that segmenting a film into a three- or four-act structure clarifies its thematic stakes. Identifying a film’s causal chains and their respective turning points reveals what is significant about its narrative conflict. It allows the viewer to explain in some detail the set of changes (both internal and external) that narrative resolution brings into effect.

STRUCTURING NARRATIVE

Studies of film narrative observe a fundamental distinction between story and plot. Story comprises the entire set of narrative events in their chronological order. No event is omitted and there are no deviations to the order in which those events take place. A plot entails the temporal manipulation of story for dramatic purposes. Viewers of a film are presented with a plot from which they have to reconstruct the story. This is because a plot may exclude certain events, skip over others, and otherwise change the order in which they occur.

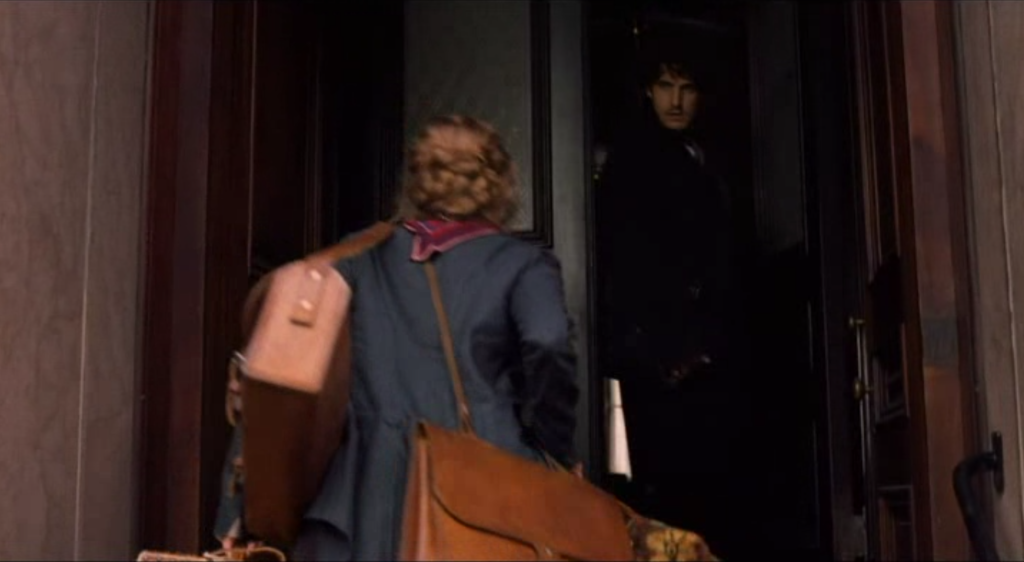

A YouTube video essay from the channel Nerdwriter1, on the science fiction film Passengers (Morten Tyldum, US, 2016), demonstrates what is to be gained from plot’s manipulation of story. The video essay speculates what difference it would make to this outer space thriller if the screenwriter and director had switched its second act with its first. In the film, Jim Preston (Chris Pratt) wakes up from his hypersleep chamber after a technical malfunction, decades before he and the rest of the ship’s passengers are scheduled to. The entire first act shows Jim attempting to adjust to life in isolation. Feeling desperate after a year alone, he wakes Aurora Lane (Jennifer Lawrence) from her chamber. He allows her to think her revival was also the result of a malfunction, rather than his own doing. A romance develops between them, but it is threatened when Aurora finally discovers that he is responsible for her being awake. The video essay asserts that this is not the most effective plot order for these story events. If the film instead began where its second act currently does, with Aurora being awakened, it would entirely alter the spectator’s impression of Jim’s character and grant more mystery to their situation. Rather than being encouraged to sympathize with Jim’s desperation over the course of the first act, the spectator (like Aurora) would be uncertain whether to trust him (Figure 3). In its current form, we know Jim is a good guy who perhaps made a bad choice in a moment of weakness. With a different plot structure, Jim’s motivations and his potential villainy are left open for Aurora (and the spectator) to determine (Figure 4). As this video essay demonstrates, the same story told with a different plotting can have radically different effects.

A story is a linear accounting of events, but a plot is often nonlinear in form, altering the order in which events are presented to viewer. One of the most commonly used devices for nonlinear plotting is the flashback, in which a temporally anterior event in the story appears as temporally successive event in the plot. More simply, in a flashback, the viewer knows that, though this particular scene follows this other one, we understand it to take place earlier in the story’s timeline. Flashbacks are sometimes explicitly marked for the viewer – for example, through dialogue (“I remember when…”), onscreen text (“Two years earlier”), or by a visual blur around the image, as seen in classical Hollywood cinema. Other times, though, the viewer must infer from the contextual cues provided by the plot how to locate an event within the story’s linear timeline. A related device to the flashback is the flashforward, in which a temporally successive event in the story appears as temporally anterior event in the plot. Or again more simply, in a flashforward, the viewer understands that we are jumping to a future event before returning to the present. The alien invasion film Arrival (Denis Villeneuve, US, 2016) exploits the ambiguity in nonlinear plotting by presenting flashforwards as flashbacks. Throughout the film, Villeneuve intersperses scenes that the viewer assumes to be flashbacks to the past of Dr. Louise Banks (Amy Adams) before the arrival of the aliens, but which are later revealed to be flashforwards to her future. The film purposefully withholds contextual information from the viewer that would have allowed spectators to correctly locate these events on a first viewing.

In addition to altering the order of story events, a plot may skip over events in a narrative ellipsis. In a famous instance of this, director Robert Bresson accounted for two years in story time in 23 seconds of plot time. Michel (Martin LaSalle), the small-time thief at the center of Bresson’s Pickpocket (France, 1959), is continually surveilled by the police for his pickpocketing so he leaves Paris for two years to allow interest in him to die down. Bresson skips over these two years entirely, only noting that they took place via a brief shot of Michel writing in his diary. Narrative ellipsis can be used to excise narratively insignificant events from the plot – it is not important what Michel did for those two years in London, only that he feels it is safe to return to Paris – but it can also be used strategically to control what the spectator knows.

This is the case with the use of ellipsis in Steven Soderbergh’s Ocean’s 11 films. Soderbergh wants to hide from his spectator narratively significant events that would otherwise fall within the chronology of his heist plot, so he skips over them and then reveals them later in flashbacks. For example, in Ocean’s 12 (US, 2004), the viewer is lead to believe that the Ocean thieves have lost their contest to the Night Fox, who successfully stole the Imperial Coronation Fabergé egg before they could. This is not the case, however. As is revealed, all of the failed attempts by the Ocean crew to steal the egg were a ruse to con the Night Fox. In actuality, they stole the egg before any of these events took place, during its transit to the museum. Soderbergh simply elides this heist, allowing the spectator to think the protagonists have failed.

A specific variation of narrative ellipsis is when the plot begins in media res either at the start of the film or at the start of a scene. In media res designates “in the middle of things,” and this narrative device involves an elision of some story events by the plot such that we are presented with a narrative situation that is already underway. For example, Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (US, 1958) begins this way. The film’s first scene joins an ongoing chase involving a police officer and a detective in pursuit of a suspect. Who this suspect is and what he did is never revealed, but what happens during this chase sets up the narrative conflict to come.

Finally, plot can manipulate a story’s timeline through the narrative repetition of events. In a story, an event occurs once, but a plot might return more than once to the same event, often for the purposes of revealing additional narrative information. For example, in Oppenheimer (US, 2023), director Christopher Nolan uses narrative repetition to establish why Senator Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.) sought to destroy the reputation of physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy), after he lead the American efforts to develop a nuclear bomb. Several times the film returns to Oppenheimer’s mocking testimony regarding Strauss’s concerns over the export of isotopes. This public humiliation motivates Strauss’s retaliatory campaign against Oppenheimer. Similarly, the film repeats an encounter between Oppenheimer and Albert Einstein (Tom Conti). Strauss believes that Oppenheimer denounced him to Einstein during this conversation. The viewer is unable to confirm this, since each repetition of this event is depicted from Strauss’s perspective, until the final scene of the film, where it is again repeated but what they say is now revealed. The plot repetition of these story events underlines how Strauss is representative of Cold War paranoia, obsessing over but fundamentally misunderstanding what is taking place.

In a subtle use of narrative repetition, Greta Gerwig’s Little Women (US, 2019), unlike the previous film adaptations of the novel, uses nonlinear plotting to draw contrasts between the March sisters as girls and as young women. Gerwig repeats one story event as a clever way to dramatize the question of which man Jo March (Saoirse Ronan) will end up with romantically. The event is a simple one: Jo ascending the front steps of her boarding house following her move to New York City. The first time Gerwig depicts this action (Figure 5), it is interrupted by offscreen dialogue from her first love interest Laurie (Timothee Chalamet), waking Jo from her sleep in an earlier timeline. The event is cut off just as the door to the boarding house is being opened. When Gerwig repeats this event later in the film (Figure 6), this time she allows it to play out in its entirety, with no interruption. The person opening the door at her arrival is Friedrich Bhaer (Louis Garrel), the man she ultimately marries. Through this formal repetition, Gerwig captures the idea Jo’s infatuation with Laurie would be only a detour before she found her true love in the unlikely candidate of Bhaer.

NARRATION

This previous section outlined plot’s temporal manipulations of story. Plot and story do not often coincide, because when we want to tell stories, we construct plots according to what we consider the most dramatically effective organization of events. So we alter the order of these events in the telling, or we skip over or repeat events as needed. As this section will examine, we also decide from whose perspective a story will be told. Constructing a plot entails choosing a narrator, or a narrating agency, which is sometimes aligned with a character in the fiction and sometimes not. Depending on whose perspective we select, the plot will be different and therefore so may be our understanding of the significance of the story. After all, it matters, for example, whether a story is narrated from the perspective of the victim or the perpetrator, of the hero or the villain, or of the protagonist or a marginal character.

If narrative is what happens, then narration is what happens from whose perspective. More formally defined, narration involves a plot’s ongoing regulation of story information. Narration determines what we know and when we know it. It specifies our “position” within the story. As just mentioned, this position might align with a specific character – if so, this character also functions as a narrator – but it is more useful to think of the film itself as a narrating agent, which might sometimes correspond to the perspective of a character and other times not. In the study of literature, we are familiar with the difference between first-person narration and third-person narration. We cannot, however, simply transplant those categories into the study of film, since film can only roughly approximate the function that pronouns (“he/she/they” vs. “I”) serve in language. Instead, scholars of film narrative frame narration in terms of two categories: omniscience and subjectivity.

Degree of omniscience

One measure of narration is the degree of omniscience it grants to its narrating agency. The more omniscient the narration, the more unrestricted is its position within the story. Degree of omniscience specifies what limitations are placed, if any, on what the camera (and therefore the spectator) “knows” one moment to the next. A convenient way to evaluate a film’s degree of omniscience is to ask whether the camera knows more than a character within the fiction. For example, a highly omniscient narration will not restrict its perspective to only one character. The camera can freely move its position between characters as needed, or it can show something unknown to any character.

This is characteristic of disaster cinema, for instance, since a film in that genre will typically give advance notice to the spectator of an oncoming devastating event, unbeknownst to the characters. In 2012 (Roland Emmerich, US, 2009), neutrino radiation from the sun destabilizes Earth’s crust, causing large-scale earthquakes. Emmerich’s omniscient narration reveals to the spectator that an earthquake is about to hit before the characters realize it. In one of these occurrences, while two main characters shop in a grocery store, the director cuts to the parking lot outside as a crack opens up in the pavement (Figure 7). Similarly, inside the store, a shopping cart veers away from a customer, as the camera tracks down to reveal more cracks in the floor (Figure 8). No characters see these warning signs, and therefore this omniscient narration prompts the viewer to anticipate the earthquake before they do (Figure 9).

The same technique is used in a more classic film, Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (Italy, 1948). The entire film hinges on a stolen bicycle. An impoverished father Antonio Ricci (Lamberto Maggiorani) gets a desperately needed job hanging posters around Rome, for which he needs his bicycle. In the scene where the bike is stolen, De Sica frames Ricci from a distance, permitting the spectator to notice one of the thieves lingering near him, eyeing the bicycle (Figure 10). Ricci does not see him. The viewer therefore comes to fear the tragic event about to befall him.

Omniscient narration constitutes an overarching viewpoint that has the freedom to move to any place or time within the diegesis. In the silent film classic The Birth of a Nation (US, 1915), director D.W. Griffith tells an epic – though quite racist – family drama against the backdrop of the American Civil War. The film depicts the intertwined fates of two families – the Stonemans of the North and the Camerons of the South – and Griffith alternates between the two sides of the war, and includes historical events such as Lincoln’s assassination. This unrestricted point of view gives the film its epic scale. In an entirely different vein, Ridley Scott’s The Martian (US, 2015) – concerning an astronaut stranded alone on Mars – also typifies a standard use of omniscient narration. The film transitions between the Mars setting, the spaceship carrying the other astronauts, and NASA on Earth, providing the spectator a privileged point of view to the narrative action. For example, neither the astronauts nor the scientists at NASA know that Mark Watney (Matt Damon) has survived and is stranded, but the spectator remains aware of his dilemma. Similarly, when a lone scientist develops a risky escape plan for Watney that is adopted by the astronauts, we see them make this decision even as NASA does not know this. With nearly every scene, the spectator maintains the most informed perspective.

At the other end of the spectrum from highly omniscient narration, films can utilize restricted narration. In restricted narration, the film confines itself to the perspective of a single character, or the spectator knows less than the characters do, or important story information is hidden from the viewer. To take a well-known example, The Sixth Sense (M. Night Shyamalan, US, 1999) carefully orchestrates each scene and camera position so as to not reveal too early that its protagonist is dead, moving through the real world as a ghost without knowing it. It is expected that this restricted point of view will cause the viewer not to notice, for instance, that other characters fail to make eye contact with the protagonist (because they cannot see him). M. Night Shyamalan’s films in general rely significantly on restricted narration to produce a sense of mystery and suspense. The Village (US, 2004) creates the impression of monsters at the outskirts of a community living in a secluded forested area because the plot restricts its perspective to the young people in the village. Likewise, A Knock at the Cabin (US, 2022) involves the appearance of four strangers at the isolated cabin of a gay couple and their child. The strangers say that one of their family members must be sacrificed or the apocalypse will happen. The viewer’s position is aligned closely with this family. We have no idea whether the strangers are telling the truth or lying, and thus the film presents us with grappling with the same ethical dilemma of whether to kill one to save all.

Genres that rely on suspense – mystery, thriller, and horror – will tend to rely on restricted narration in order to withhold information from the viewer – say, the identity of a murderer. Like Shyamalan, the films of David Fincher often appeal to this type of narration. In Gone Girl (US, 2014), the first act of the film is told from the perspective of Nick Dunne (Ben Affleck), who believes that his wife Amy (Rosamund Pike) has been kidnapped from their home or murdered. The film confines itself to Nick’s cooperation with the police investigation until it becomes clear that detectives suspect him of the crime. In a narrational twist, the film assumes Amy’s perspective. Not only is she not dead but also she is purposefully framing her husband for her own disappearance. The remainder of the film utilizes more omniscient narration as it alternates between the perspectives of Nick and Amy. In his earlier film, The Game (US, 1997), Nick Van Orton (Michael Douglas) is gifted an interactive game by his brother, but when the game involves the trashing of Van Orton’s home, sabotage at his job, and potential threats on his life, he suspects that something more nefarious is taking place. Any stranger he meets might be a part of the game just as any vehicle he enters or object he picks up might be as well. The viewer, like Van Orton, is not given enough information to determine what is real and what is only gameplay. Fincher has said that he had to studiously avoid close-ups because otherwise the spectator would assume they were being clued in to something significant. As a director, he had to be careful not to “tip his hand” to viewers in order to keep them closely tied to Van Orton’s paranoia. Finally, Fight Club (US, 1999) pulls a similar trick to The Sixth Sense. By restricting the narrational point of view of the film to its unnamed protagonist, the director is able to conceal the fact that another character – Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt) – is not real, only the imagined alter ego of the protagonist. For much of the film, the protagonist only learns, as we do, of the things Tyler has done after the fact, not realizing that he in fact is Tyler.

It is essential to remember that a film not simply omniscient or restricted in its narration. A film can adjust the degree of omniscience throughout, depending on the dramatic needs of the story. An example of this was given above, where in Gone Girl, the relatively restricted narration of the first act becomes more omniscient once it is revealed that Amy is still alive. We can also point to another earlier example from Spider-Man: Homecoming, which utilizes relatively omniscient narration throughout. However, when it suits the storytelling interests of the film, it momentarily shifts to a more restricted viewpoint. For instance, although the film freely features scenes with arms dealer Adrian Toomes, even when Spider-Man is not present, the film hides from the viewer his connection to Liz (he is her father). This piece of information is only learned when Peter learns it, when picking up Liz for the prom. The film could have structured this revelation differently. If it had been disclosed to the viewer that Toomes is Liz’s father before Peter knows it, then we would feel anticipation of an upcoming conflict that Peter is not aware of yet. Instead, the film wanted this information to be a surprise.

To summarize, the degree of omniscience in narration specifies where the viewer is positioned within the story and determines how much information we have relative to the characters and when we learn it. In a highly omniscient narrative, the narrational point of view “stands above” the story, able to survey and supervise what it wants. In a highly restricted narrative, this point of view “stands within” the story, able to only capture a partial view of events and aware that there is information that remains undisclosed.

Degree of subjectivity

This measure of narration considers the degree to which a film provides access to the internal mental states or perceptual point of view of its characters. At which points, if any, are we “inside the head” of a character? Subjective narration is somewhat tricky in film, since the default position of a camera is to objectively record the action, leaving the viewer to infer the psychological interiority of characters through dialogue and acting. We are generally “outside” the character. More objective narration relies on external cues to communicate narrative information. It specifies a more “indifferent” narrational perspective that does not emphasize what a character may feel or think about a situation, only how they behave.

Film makes use of specific formal devices to produce moments of subjective narration. They include the following:

Internal voiceover. In this device, a character narrates on the soundtrack their internal thoughts and feelings. The spectator hears the character’s reactions to a situation. For example, this device is used extensively in The Haunting (Robert Wise, US, 1963). The film foregrounds the psychological reactions of its protagonist to the strange supernatural phenomena she experiences in the haunted Hill House. It is also used in Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, US, 1960), first when Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) flees with the stolen money (we hear her working out when her employers will discover the theft) and at the conclusion when the internal monologue of Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) is heard in the voice of his mother.

Subjective flashback. In this variation of the flashback, what the spectator sees represents the memory or imagination of an earlier event rather than an objective depiction of it. The flashback is explicitly or implicitly marked as the character remembering something, allowing the spectator the assumption that what is seen may not be accurate representation of what happened. A notable example of a subjective flashback can be found in Ratatouille (Brad Bird, US, 2007). When stuffy food critic Anton Ego (Peter O’Toole) tastes the title dish of the film, he is visually transported back to his childhood, to when his mother had prepared the same meal (Figures 11-13).

Dream sequences or other depictions of altered states of mind. A film may want to simulate for the spectator the experience of a character undergoing an altered state of consciousness. This might include dreaming, drunkenness or being stoned, delirium or confusion, drowsiness or losing consciousness, hallucinating, shellshock or being dazed, or other similar subjective states. The director might make use of a subjective camera, where the camera seems to be tied to the movements of a character. Let’s identify a few examples. In the silent film Shoes (US, 1916), director Lois Weber visualizes the anxiety of a young woman who cares for her family on a meager wage by depicting an imaginary “hand of poverty” suspended over her bed (Figure 14). In another silent film, The Fall of the House of Usher (France, 1928), director Jean Epstein uses superimposed images of Madeline to express the feeling of having her life force robbed by her husband’s magical portrait of her (Figure 15). Finally, in Spellbound (Alfred Hitchcock, US, 1945), the director recruited surrealist artist Salvador Dali to design sets for a dream sequence (Figure 16).

Point of view shot. While the previous devices emphasized a character’s mental states, this commonly used device involves a perceptual alignment of what the camera sees with what a character sees. A point of view shot is one where the camera shows the visual perspective of a character, as if the film were looking out of the character’s eyes. The camera assumes the physical position of the character within the space and appears to display what they see (Figures 17-18). This can sometimes be used to indicate a discrepancy between their subjective perception and an objective view of the event through a form of visual distortion. For example, a point of view shot can be blurry, indicating that the character is unable to discern what is in front of them. On rare occasions, filmmakers have experimented with constructing an entire film around a single character’s point of view. The film noir Lady in the Lake (Robert Montgomery, US, 1947) aligned its spectator with the visual point of view of the film’s detective protagonist. The gimmick was that viewers would experience what the detective does and would try to discern clues for solving the murder case along with this character.

As with omniscience, the degree of subjectivity in a film’s narration is not a binary choice between subjective and objective. A film’s narration can be positioned close to a character’s perspective without necessarily assuming the mental or perceptual point of view of that character. In other words, we don’t have to be only inside a character’s head in order to point to instances of subjective narration. Consider the scene from Little Women (Gerwig, 2019) where Laurie helps Jo to escort her injured sister back to the March household following a ball. It is his first time in the home, and even though the camera does not adopt his visual point of view, the scene nonetheless emphasizes his reactions to this female-dominated space. The March sisters huddle around their injured sister in front of the fire, as their mother welcomes Laurie. The film repeatedly cuts to reaction shots of Laurie as he watches the sisters interact, and it is clear that, in contrast to the cold atmosphere of his own home, he is drawn to this warm and inviting space (Figures 19-21). Film analysis requires that one be attentive to whether a film, through its framing and editing choices, tends to favor, privilege, or single out one character’s position over the others. The less a film seems to center a particular character, the more objective is its narration. This would be the case had this scene from Little Women played out without these reaction shots. Instead, even though we must still infer what Laurie is feeling at this moment, the film is nonetheless signaling it is his personal reactions that matter here.

NARRATIVE, TECHNOLOGY, AND INDUSTRY

To this point, we have considered the intrinsic features of film narrative, examining how plot is organized in response to the internal features of story. However, film and television are industrialized art forms, and therefore we must also consider the extrinsic determinations of narrative. What this will show is that the particular form a plot takes is not solely affected by the nature of the character or story, but also by the conventions and standardized practices of the medium as a whole. We will look at three of these extrinsic influences on narrative: genre, television distribution, and franchise filmmaking.

Genre

A genre is a way of classifying films into recognizable categories based on shared characteristics, such as character types, visual iconography, and narrative conventions. Some film genres include horror, musical, action-adventure, romantic comedy, and crime film. These broader categories can be further divided into subgenres, such as found-footage horror films, the heist movie as a type of crime film, or the distinction between a psychological thriller and an erotic thriller. Filmgoers are accustomed to thinking of cinema in terms of genre. They use it as a guide for deciding what films might interest them, just as film distributors use it to market their films to audiences, as seen for instance, on a Netflix home page. This is what film scholar Rick Altman refers to as the pragmatic approach to film genre, because it recognizes that genres function in a market to align the interests of institutions and audiences, by matching the characteristics of a cultural product (i.e. a film) to the expectations of its intended consumers (i.e. the audience).[2] Anyone who has ever complained that a movie trailer misrepresented the film it advertised knows when the pragmatic function of genre has failed.

Altman has further defined film genre according to a semantic and syntactic approach. The semantic aspects of a genre film refer to its iconographic elements, meaning the visual components that make it recognizable as a member of a specific genre category. For instance, when watching a western, one expects the film to include cowboys, Native Americans, a frontier setting, a saloon, a bordello, guns, horses, and so on. This iconography is clearly distinguishable from a science fiction film, which may involve outer space, aliens, spaceships, forms of advanced technology, and so on. No one film will include all of the iconographic elements associated with its genre, and these elements can be shared across genres. Moreover, a genre hybrid may combine elements from different genre categories. Jordan Peele’s Nope (US, 2022) is both a western and a science fiction film, as is Star Wars (George Lucas, US, 1977).

The syntactic aspects of a genre refer to how these iconographic elements are arranged into a meaningful structure, just like the syntax of a sentence organizes separate words into a meaningful whole. Therefore, a western does not just feature cowboys on the frontier. It organizes those elements into a narrative framework that signifies the confrontation between civilization and wilderness. A horror film or a science fiction film does not just feature a ghost/monster or an alien creature. They organize those elements into a framework involving the encounter of the human with the non-human other.

Insofar as a film is a member of a particular genre, then, its narrative components will be influenced by the semantic and syntactic conventions of that genre. Genre films are pleasurable because they offer familiar templates with minimally sufficient differences to distinguish any one film from the others. A romantic comedy, for example, has its familiar beats: the meet-cute, the opposites-attract or enemies-to-lovers central couple, the quirky best friend, and the last-minute grand romantic gesture. A pair of Nora Ephron films from the 1990s, Sleepless in Seattle (US, 1993) and You’ve Got Mail (US, 1998), both starring Meg Ryan and Tom Hanks, follow these beats closely, though in the first film, geographical distance is the primary obstacle to romantic union while in the later film, they are business competitors, her small bookstore being threatened by his large bookstore chain. Other romantic comedies purposefully break from these conventions, though not so much as to fall outside of the genre. In (500) Days of Summer (Marc Webb, US, 2009), for example, the film begins with the couple’s break-up. The spectator knows it ends badly, and this informs our understanding of the film as its plot jumps around to different moments in their relationship, allowing us to see why it failed.

Television Narrative

The narrative form of television is highly determined by the technological parameters of its delivery to the consumer and by its industrial structure. What are the basic elements of television narrative? Scholar Michael Z. Newman identifies three levels around which TV narratives are structured: beats, episodes, and arcs.[3] An episode is a discrete narrative segment in a television series, traditionally airing either daily or weekly. Episodes are comprised of beats, a minimal unit of narrative action, where typically the main plot line of a half-hour episode will have 4-5 beats. Finally, arcs designate narrative segments that extend across episodes, often lasting for the duration of a television season.

Scholars of television distinguish between two forms of narrative organization: episodic and serialized. In episodic television, the episode is a self-contained narrative unit, meaning that narrative problems are introduced and resolved within the span of a single episode (or sometimes two). Traditional sitcoms tend to be highly episodic. For example, The Simpsons (FOX, US, 1989- ) is organized in this way, in that not only does it resolve plot lines each episode but also it tends to reset to initial conditions (Lisa and Bart have been in the same grades at school for more than two decades). Other television formats such as game shows or talk shows are likewise episodic in form. In serialized television, episodes tend to be linked by narrative arcs that extend across several episodes, a season, or the entire series run. This is now a common practice, even in sitcoms, but it came to prominence in quality television programming of the 1990s with shows such as The X-Files (FOX, US, 1993-2002) and Buffy the Vampire Slayer (WB/UPN, US, 1997-2003). Buffy, for instance, introduced the concept of the “big bad,” where each season was defined by a single villainous character. The X-Files, meanwhile, organized single episodes around specific supernatural or extraterrestrial mysteries while sustaining a broader conspiracy involving the government cover-up of aliens across the entirety of the series.

What are the industrial or technological conditions that affect episodic and serialized television? In other words, how do the ways that television is distributed to audiences help to shape its narrative structures? This is especially apparent if we contrast early television (the broadcast era) to contemporary television (the streaming era). Let’s look at changes in two aspects of the medium: commercials and syndication. In the broadcast era, when television was distributed over the public airwaves across only three channels, it operated under a multiple-sponsor model. This meant that audiences would receive free programming (after the cost of a television set) and the television networks would generate revenue by selling advertising time. Commercials interrupted television shows at regular intervals. When scripting for television therefore, writers had to accommodate these planned interruptions, and they did so by distributing narrative beats around these commercial breaks (for example, placing a cliffhanger before a break). Moreover, because all television time was advertising time, the length of single episodes was precisely regulated. A half-hour sitcom comprised 22 minutes of programming, for instance, setting firm constraints on how long TV writers had to work with. By contrast, the streaming era, where television is distributed over the Internet, has eliminated these restrictions. Excepting recent developments, streaming services deliver content to subscribers commercial-free. Subscriptions and data mining replace advertising revenue. This means that writers do not have to organize their stories around regular commercial breaks, altering the rhythms of television narrative. Since streaming services are not reliant on commercials, they can also offer television showrunners freedom to deviate from standard episode lengths. Viewers of recent television will likely have noticed that episode runtimes often vary across a season.

The other aspect we can consider is syndication. Syndication refers to the off-network rebroadcasting of television episodes, or in other words, reruns. For decades, this is how television producers recouped the cost of production. The original broadcast of a television program was typically deficit-financed, but once a show exceeded 100 episodes, it was eligible for reruns on a cable channel, for instance. The licensing fees for these reruns are how a show turns a profit. What does this have to do with the structure of television narrative? When syndication was the primary funding model for television in the broadcast era, television narratives tended to be more episodic. The simple reason for this was that it was not guaranteed that a viewer would see the episodes of a show in syndication in their original order. Since episodic television involves self-contained episodes, nothing would be lost in viewing them out of order.

This has changed in the streaming era. For its original programming, there are no reruns on Netflix or Hulu. The show is available in its entirety on the platform indefinitely. Shows for streaming services are not deficit-financed, dependent on subsequent syndication, but are instead funded upfront. The consequence of this industrial and technological shift in the distribution of television is that shows can be more serialized in their narrative structures than before. Some scholars have described this as the era of “complex TV,” since viewers’ ability to watch and re-watch a program at will allows for more complicated plotting and intricate story structures.[4] There is no shortage of examples, from the epic world-building of Games of Thrones (HBO, US, 2011-2019), to the slow burn of Breaking Bad (AMC, US, 2008-2013) or Mad Men (AMC, US, 2007-2015), to the narrative experimentation of Maniac (Netflix, US, 2018).

Franchise filmmaking and transmedia storytelling

This section considers some of the ways that narratives extend beyond any one single film. As with genre films, where studios aim to give audiences familiar stories in slightly new packaging, there are incentives within the industry to exploit popular characters or story worlds across several movies until they exhaust consumer demand for them (and sometimes not even then). A common example is the sequel, where the diegetic world of one film is carried over into a second film, or the prequel, where a subsequent film fills in the backstory or unexplored dimension of a previous film. Both sequels and prequels are standard components of franchise filmmaking, which refers to a set of narratively interconnected films, typically involving the placement of the same characters in new narrative situations (for example, the Halloween films) or the gradual unfolding of a single narrative across several films (for example, the Harry Potter films). Contemporary filmmaking has also introduced the term requel, as a means of designating a film that is somewhere between a sequel and a franchise reboot, such as The Matrix Resurrections (Lana Wachowski, US, 2021) or Creed (Ryan Coogler, US, 2015). A requel returns to the story material of an earlier film or franchise, but breaks from the continuity of the original story and often introduces new characters while retaining “legacy” characters.

Contemporary moviegoers will also be familiar with the idea of “cinematic universes,” spearheaded by Marvel, in which an otherwise disconnected set of characters and plot lines are established as existing within the same diegetic world. The Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) is an example of what film studies calls transmedia storytelling, which involves the expansion of a narrative world across different media, including film, television, books, comics, and the like. Transmedia storytelling is not adaptation (adapting a book into a film, for instance). Rather, it entails extending the narrative world across media formats, such that each iteration adds a new dimension. For example, the Disney+ show Wandavision (US, 2021) relies on viewers’ knowledge regarding Vision’s death in the MCU films, since it addresses Wanda’s failure to accept losing him. Or, the eight-film Harry Potter film franchise has been supplemented by both the Fantastic Beasts films, which precedes the events of the films, and a stage play Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, which takes place years after the defeat of Voldemort.

[1] See, for instance, Kristin Thompson, Storytelling in the New Hollywood: Understanding Classical Narrative Technique (Harvard University Press, 1999).

[2] Rick Altman, Film/Genre (British Film Institute, 1999).

[3] Michael Z. Newman, “From Beats to Arcs: Toward of Poetics of Television Narrative,” Velvet Light Trap 58 (1): 16-28.

[4] Jason Mittell, Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling (New York University Press, 2015).