Cinematography

If mise en scène pertains to the elements of filmmaking that overlap with the theater, to the staging of narrative action, then cinematography refers to what is unique and specific to filmmaking as a photographic medium which records that action. This chapter outlines many of the fundamental components of cinematography that filmmakers have to consider when making a movie.

FRAMING

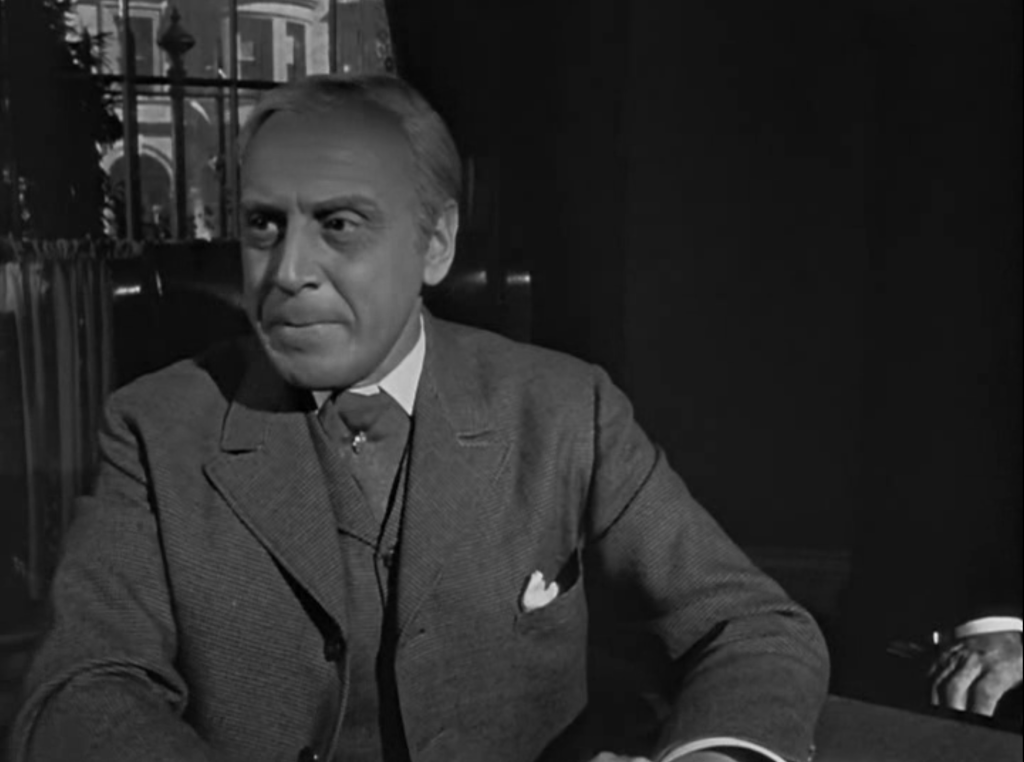

Framing always involves a choice, since it sets limits on what a film shows of the mise en scène. In cinema’s earliest years until the 1910s, a film would present its narrative action at some distance from the camera, typically with actors arrayed laterally across the space. Known as tableau staging, this type of narrative presentation demonstrates the influence of theater on early cinema, since that distanced perspective resembles the single point of view of a theatergoer looking at a stage (Figure 1). Especially as films expanded to feature length, practitioners of the medium would break from this theatrical convention to develop a mobile point of view through framing choices that would no longer limit the spectator to a stationary viewing position. Filmmakers could now place the camera in different orientations to the narrative action, sometimes closer and sometimes farther, or sometimes from a new angle, depending on what the story demanded from one moment to the next.

A mobile point of view was needed because tableau staging could create problems for narrative clarity. Consider the 1905 film Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son, made by the Biograph company. Across its 10-minute running time, it tells the simple story of a thief who steals a pig and then is caught. It is an example of a popular genre of the period, the chase film, where most of the narrative action consists of a series of shots linked by the chase between the pursuers and the pursued. However, the action that initiates this chase – the stealing of the pig – is easy to miss. The first shot features a crowded mise en scène of townspeople, musicians, and jugglers continually milling about. The shot contains several character actions and therefore several points of visual interest. At one point a fight breaks out on the right side of the frame. What should the spectator look at in this scene? Is the fight the main action or something else? The pig is stolen just before the shot ends, but only the eagle-eyed viewer might see it happen. We’ve included a still image of the moment it takes place (Figure 2). Can you spot it?

This problem of how to tell an intelligible story that a viewer can coherently follow is what film’s mobile point of view is meant to solve. The narrative hinges on the action of stealing the pig, so the use of framing to isolate this action, via a close-up, is how a mobile point of view continually guides the viewer’s attention to essential narrative information. Avant-garde filmmaker Ken Jacobs used Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son as the basis for his 1969 experimental film of the same name. Stretching the 10-minute runtime to nearly two hours, Jacobs rephotographed the short film, repeating shots, slowing them down, and isolating different parts of the frame. Jacobs’ film reflects on the way films narrate stories by controlling point of view through framing choices, by determining what a spectator sees and when.

In classical form, film’s mobile point of view is closely tied to the demands of story. Changes in framing typically follow the logic of the narrative, emphasizing particular characters or elements of mise en scène as needed. In anti-classical form, framing may operate independently of narrative clarity. In this mode of narration, framing can actively ignore or deviate from important narrative information.

What framing does is establish a point of view toward the narrative action. It determines what the viewer does and does not see of that action. It sets limits of what that viewer knows. Thus, while framing is an act of composition, turning the world into a picture to be seen, it is also fundamentally a means of guiding attention and directing focus.

TYPES OF FRAMING

As a description of camera position, framing is typically classified along three dimensions: distance, angle, and height. Each frame is the result of decisions about where to place the camera relative to the action.

Camera distance

This aspect of framing indicates how close or far away the camera is from the depicted subject. It is easiest to distinguish differences in camera distance in terms of how a human body is framed (Figures 3-7, Figures 8-12).

Extreme long shot. This type of shot, because the camera is positioned at a significant distance from the action, emphasizes the surrounding environment. A character would appear relatively small in size relative to this environment, taking up only a minor portion of the frame. It is commonly used for exteriors, especially where the film foregrounds a landscape or cityscape.

Long shot. This type of shot corresponds to a depiction of the human form where the whole body (or nearly so) is visible. This is more commonly used for interiors, where a character or several characters are seen within the space, but unlike the extreme long shot, the emphasis is on these human subjects rather than the environment.

Medium shot. This type of shot depicts a human subject typically from the waist up. It is commonly used in scenes that emphasize dialogue between characters.

Close-up. This type of shot corresponds to the head/face of a human body. Since it foregrounds the face, it is commonly used to emphasize facial expressions or subtle reaction shots. Close-ups are also often used to select out details in the mise en scène, such as a narratively significant prop or element of the set.

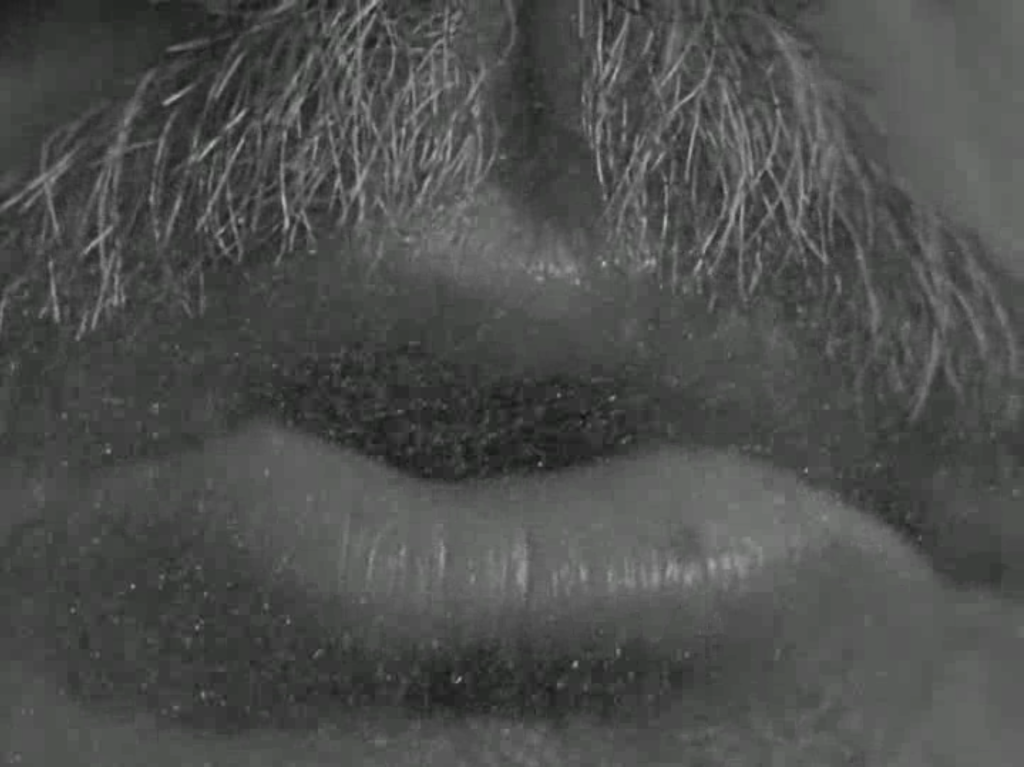

Extreme close-up. This type of shot typically depicts a part of the face or a small detail of an object.

The boundaries between these classifications of camera distance is flexible, and often film analysis makes use of intermediate descriptions such as medium long shot and medium close-up for greater precision.

Camera angle

This aspect of framing describes the direction from which the camera films the action.

Eye-level. Designating a “straight-on” framing, the camera is positioned at a “flat” or level perspective relative to the depicted subject. This framing can be considered a default or neutral camera position, and it is by far the most commonly used (Figure 13).

High angle. This framing shows the action from some angle above, looking down on the depicted subject (Figure 14).

Low angle. This framing shows the action from some angle below, looking up at the depicted subject (Figure 15).

Overhead. A specific variation of the high-angle shot, this framing shows the action from directly above, where the camera assumes a perpendicular position to the depicted subject (Figure 16).

Canted. Deviating from a level position, in this framing, the camera is titled horizontally, either to the left or right, depicting the action from a diagonal or skewed perspective (Figure 17).

Camera height

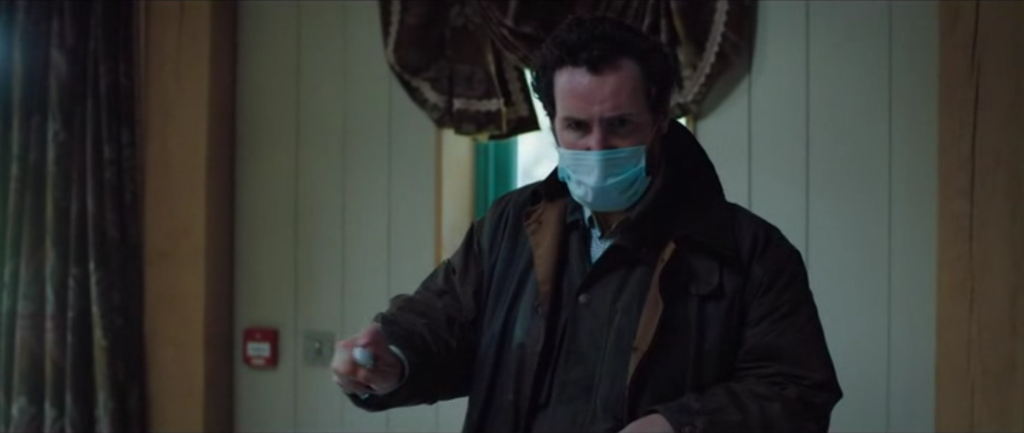

This aspect of framing describes the vertical positioning of the camera relative to the action. It is closely related to camera angle, since in high-angle shots, the camera assumes a vertical position above the subject, and vice versa for low-angle shots, but they are distinct. Consider a shot that whose angle is eye-level but whose vertical position is floor-level, as seen, for example, in this shot from David Fincher’s Zodiac (US, 2007). Fincher selected this floor-level height to emphasize the shoes of the criminal suspect arriving for his police interrogation, since that has been an important detail in the narrative (Figure 18).

FRAME DIMENSIONS

The frame is a rectangle, but it does not always have the same dimensions. Film directors make decisions about the size of the image for both stylistic and budgetary reasons. There are two primary aspects that affect the relative dimensions of the frame: film gauge and aspect ratio.

Film gauge refers to the measurement (in millimeters) of the width of the filmstrip on which a photograph is registered as it runs through the camera. This width varies depending on the film format being used. The most common format is 35mm, which was developed at cinema’s invention and remains the industry standard. Another format, 16mm, was introduced in the 1920s, along with lightweight cameras, allowing for more mobile filmmaking, as utilized in newsreel film. An upgraded version of the 16mm called Super 16 continues to be used by some Hollywood filmmakers. Even narrower than 16mm, 8mm film was introduced in the 1940s. It produced comparatively grainy images, but that was less of a concern for its primary function: as a format for amateur filmmakers in the years before personal camcorders or smartphones. 8mm was the format for home movies. On the opposite end of the spectrum is 70mm, which offers directors wide latitude for image composition.

Aspect ratio refers to the ratio between the width of the image to its height. It functions independently of film gauge, meaning that a single gauge can accommodate different aspect ratios through masking, where the image is cropped horizontally. Aspect ratio is therefore the most important factor for the dimensions of the projected image. Theoretically, an image can be sized however a film director wishes, but it is most common to use a standardized aspect ratio, which are as follows:

1.37:1 Academy ratio, the traditional aspect ratio during Hollywood’s studio era (1930s-1960s) (Figure 19)

1.85:1 Standard widescreen, grants greater horizontality to the image than the Academy ratio (Figure 20)

2.35:1 Anamorphic widescreen, a lens that squeezes a larger image into a smaller frame (Figure 21)

4:3 The aspect ratio of analog television before the introduction of widescreen-formatted HDTV

Expressive Uses of Aspect Ratio

Since aspect ratio only describes the size of the rectangle of a film image, it is not often an object of manipulation for artistic purposes. The dimensions of the image obviously affect stylistic considerations such as the composition of mise en scène and framing, but aspect ratio most often remains unchanged in a film once those dimensions are selected. There are exceptions, however.

In The Grand Budapest Hotel (US, 2014), director Wes Anderson switches between aspect ratios to mark storylines that take place at different historical moments (Figures 22-24). Each of the three time periods has a corresponding aspect ratio: 1.37:1 for the main storyline in the 1930s, 2.40:1 (anamorphic widescreen) for the 1960s, and 1.85:1 (standard widescreen) for the 1980s.

For Dunkirk (US/UK, 2017), director Christopher Nolan shot much of the film (around 75%) in IMAX 70mm, while the remaining portion was shot in standard 70mm. IMAX screens are taller than a standard movie theater screen. Therefore, for those portions shot in standard 70mm, the viewer would see black bars above and below the image, since those portions were not designed to fill the screen.

Contemporary filmmakers have shown interest in playing with aspect ratio. Director Zack Snyder utilized an atypical aspect ration of 4:3 for Justice League (US, 2021) – the so-called “Snyder cut” – because he thought the sense of verticality stemming from the increased height of that ratio when compared to widescreen formats would enhance the grandeur of the superhero narrative.

In Mommy (Canada, 2014), director Xavier Dolan used a 1:1 image ratio, a perfectly square image meant to remind the spectator of Instagram. At two moments in the film, however, the image visibly expands horizontally to widescreen dimensions. In one of these instances, the film’s teenage protagonist literally reaches out his hands to push apart the sides of the frame. In the context of the film’s narrative, this change in aspect ratio expresses the character’s momentary feelings of freedom, and once that feeling subsides, the image contracts to its square formatting.

CAMERA MOVEMENT

Just as the camera can assume various static positions relative to the action, it can also change its position within a shot by moving. Camera movement can be considered to be choreographed action, with the camera sometimes moving in a coordinated manner to the action and sometimes moving independently of it. Film practitioners have developed a set of conventional camera movements that are classified according to the type of motion executed by the camera. All of these can be considered as types of mobile framing.

Pan. A pan is a horizontal scanning of the mise en scène, as the camera pivots left or right from a stationary position. It is analogous to a person standing still while moving their head left or right.

Whip pan. In this specific variation of a pan, the same horizontal movement is executed much more quickly, creating a visual blur between the camera’s starting and end positions.

Tilt. A tilt is a vertical scanning of the mise en scène, as the camera pivots up or down from a stationary position. It is analogous to a person standing still while moving their up or down.

Tracking shot. Unlike in a pan or tilt, this camera movement involves the physical displacement of the camera within the space (i.e. the camera is no longer stationary). It is called a “tracking shot” because the camera is typically placed on tracks laid down on set or on a wheeled cart called a dolly. The tracks create a recognizably smooth movement allowing the camera to capture the action while running alongside or in some other position relative to it. A tracking shot is often used to describe camera movements that move within the set along the ground.

Track-in (or push-in or dolly-in). A specific variation of the tracking shot, this camera movement involves moving closer to the action from a more distanced position. The camera pushes forward toward the action.

Track-out (or dolly-out). A specific variation of the tracking shot, this camera movement involves moving farther away from the action from a more proximate position. The camera recedes or moves backward away from the action.

Follow shot. A specific variation of the tracking shot, this type of shot places the camera directly behind a character, usually at a slightly high angle, as that character moves forward through the space. In other words, the camera “follows” the character.

Handheld. This mobile camera, rather than being affixed to tracks or a dolly, is held by a camera operator. This often results in a visible shake or wobble in the image.

Steadicam. Steadicam refers to a camera technology developed in the 1970s that attached to the camera operator through a gyroscopic rigging. It is a handheld camera movement that nonetheless produces a visibly smooth motion.

Crane. Whereas a tracking shot moves along the ground, a crane shot films the narrative action from an elevated position. The camera is affixed to a mechanical crane that hovers above the action.

Aerial. Whereas a crane is relatively near to the ground, an aerial shot presents an image filmed from a camera attached to an aircraft, often a helicopter or more frequently in recent years, unmanned drones.

REFRAMING

A film director can opt to use camera movement instead of editing to connect pieces of narrative action. Consider this simple example: A scene involving two characters in conversation could alternate through editing shots of each speaker, but a filmmaker could elect instead to pan between them, moving the camera back and forth as each character speaks. Reframing refers to the repositioning executed through a camera movement. For instance, if a character is seen in a medium shot reading a book and then the shot tracks-in for a close-up of the book’s cover, we would say that the film reframes to show the spectator the book’s title, or that the film reframes from a medium shot to a close-up. Reframing, in other words, links two or more distinct compositions or blocking of the actors through the movement of the camera, just as in dance choreography, a movement performed by the dancer will connect distinct poses.

OFFSCREEN SPACE

Any choice in static framing (distance, angle, and height) and mobile framing (all camera movements) creates a separation between what is visible in the image and what is invisible. The frame establishes a boundary between onscreen space and offscreen space. There are six areas of offscreen space: the four corresponding to each side of the frame (left, right, above, and below) and the two along the z-axis (the area behind the set and the area behind the camera).

Filmmakers can “activate” offscreen space in a number of ways. For example, in Rosemary’s Baby (US, 1968), director Roman Polanski uses an unexpected framing to emphasize the point of view of Rosemary (Mia Farrow). Rosemary is the victim of a satanic cult in her upscale New York apartment building in a scheme to deliver the Devil’s baby. When one of the members of the coven learns that Rosemary is pregnant, she steps away to the bedroom to make a phone call to share the news. Polanski’s cinematographer initially framed the shot with Minnie Castavet (Ruth Gordon) in full view, but Polanski altered the staging so that, from Rosemary’s perspective, only a portion of her body would be visible (Figure 25). Rumor has it that when audiences watched this scene they craned their heads to try to peer around the door blocking the phone call.

It Chapter Two (Andy Muschietti, US, 2019) stages a very similar scene. Beverly Marsh (Jessica Chastain) returns to her childhood home, now occupied by an older woman, but unbeknownst to her, the woman is a manifestation of the demonic clown Pennywise (Bill Skarsgård). To Beverly, the elderly woman appears sweet and welcoming, but offscreen space is used to suggest that something more sinister is taking place. First, as Beverly sits in an armchair, the film reframes to the right to reveal the woman standing still in the background until she jerks erratically and then steps out of view. This framing cues the spectator to anticipate something that Beverly does not. Second, as Beverly begins to realize what is happening, the director frames her over the shoulder peering through the archway to the other room, which unlike in the previous shots, remains too dark to see anything. Holding the shot on this dark portion of the frame “activates” this offscreen space, priming viewers to sense what is not yet present.

FOCUS AND LENSES

The film camera is an optical system that registers an image by controlling for light as it passes through a lens. Filmmakers have significant variety in the type of lenses they can use, and in collaboration with their director of photography, they will select lenses with the characteristics that correspond to their overall intended look for the film. One important characteristic of a lens is its depth of field. Depth of field refers to the range of the image that is in crisp, clear focus. Imagine an invisible line extending outward from the camera into the profilmic space. Depth of field describes how broad of a range along that line will result an image of sharp focus, such that an object on the line which falls outside that range will appear out of focus.

A narrow depth of field will result in shallow focus. If we divide up the apparent depth of an image into separate planes, we can distinguish between a shot’s foreground, middle ground, and background. A shallow focus will typically keep only one plane of the image in sharp focus, as for example, an image where a character in the foreground is clearly visible but the background area behind her is not, and vice versa (Figures 26-27). Or a filmmaker might target the middle ground, placing a character in sharp focus in that space while allowing both foreground and background elements to remain blurry (Figure 28).

A deep focus image, by contrast, has a broad depth of field that keeps all the planes of the image in clear focus, extending from the foreground to the background (Figures 29-30).

It is commonplace for a director to shift focus within a single shot. This is called a racking focus, or rack focus. To take one example, a shot might initially have its foreground in focus and its background out of focus. The film might then rack focus, such that now the background is in clear focus, while the foreground is blurry. This visible change in focus is often intended to draw the viewer’s attention to different parts of the frame in response to the narrative action.

Lenses can also distort how viewers see reality when presented as a moving image. By selecting different types of lenses, filmmakers can manipulate the perceived dimensions of the image. In addition to depth of field, another important feature of a lens is its focal length, which is typically characterized as short or long. In fact, depth of field and focal length are related aspects of a lens: A shorter focal length produces a broader depth of field, whereas a longer focal length produces a narrower depth of field. Lenses of short focal length are called wide-angle lenses, and lenses of long focal length are called telephoto lenses. These lenses fall on opposing sides of what are called normal lenses, whose focal length produces an image that closely resembles ordinary perception, preserving the same relative dimensions in object size and comparative distance between those objects.

What type of visual distortion does each lens produce? A wide-angle lens, because it squeezes a wider area of the profilmic space into the standard frame, will have two primary effects. First, it tends to bend the image at its edges, where vertical lines at the frame’s edge appear slightly bowed (Figure 31). Second, it tends to exaggerate the apparent distance between objects in the foreground and those in the background. Whereas in reality those objects might be relatively close to each other, the image makes them appear more distant (Figure 32).

A telephoto lens will visually distort the image in opposing ways. Instead of exaggerating the distance between objects in different planes of the image, it tends to compress them, flattening the image (Figure 33). For instance, a character walking toward the camera filming with a telephoto lens will appear to take longer than normal to cross that distance, because the image does not render its magnitude (Figure 34).

Similar to the way a rack focus involves a shift between in the depth of field of an image, a zoom lens carries out a shift in focal length. In a transition from wide-angle to telephoto, a zoom shot will appear to move closer to an object (the object will enlarge in the frame), and in the reverse example, from telephoto to wide-angle, the shot will appear to move away from an object (the object will diminish in size). There is no camera movement in zoom shot, only the simulation of camera movement.

TIME AND FRAMING

Each shot of a film has a precise duration, and film directors know well that the timing of a shot can affect its meaning and tone. We call this duration shot length, and it is usually measured in seconds. Film scholars have used this metric to make distinctions between films across historical periods or across genres. The average shot length (ASL) of a film from classical Hollywood is likely to be longer than a contemporary film, which is partly why older films tend to feel slower to today’s viewers, just as the ASL of a comedy tends to be shorter than that of a drama.

A shot of extended duration is called either a long take or a sequence shot. Note the difference between the terms long shot and long take. The first refers to an aspect of camera distance, while the second refers to shot length. It is important to not confuse the two. The term sequence shot underlines the idea that a shot of extended duration will often utilize multiple reframings or changes in blocking. Digital cameras have made long takes more easily achievable, since a memory card can record for much longer than a physical reel of film, and this has made long takes a more common device in recent film and television, including those that present their narrative action in what appears to be a single take. Examples of the latter include 1917 (Sam Mendes, US, 2019), Birdman (Alejandro González Iñárritu, US, 2014), as well as episodes of Mr. Robot (USA, 2015-2019) and The Bear (FX, 2022- ).

Filmmakers can also temporally manipulate the speed of the action. This type of manipulation exploits the difference between the rate of recording and the rate of projection. The standard rate of projection for film is 24 frames per second (fps). Remember that in the pre-digital era film produces a moving image out of still photographs, which when projected at a sufficiently fast rate, will appear as continuous movement to a viewer. The initial rate of projection in silent cinema stabilized around 16 fps, which is why some of the movements in those early films can now appear to stutter or jerk. Contemporary film directors are experimenting with frame rates that are much faster than 24 fps. For example, Peter Jackson shot The Hobbit films (US, 2012-2014) at 48 fps, while Ang Lee pioneered the use of 120 fps on Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk (US, 2016). High frame rates produce images of extremely sharp resolution that many viewers have found to undermine the credibility of the diegesis (i.e. the images look “too real”).

We can consider three types of temporal manipulation of a film’s frame rate: slow motion, fast motion, and the freeze frame. Slow motion is an optical effect where the rate of recording is more than the rate of projection. Assuming a standard rate of projection of 24 fps, if the narrative action is filmed at a higher rate than that, then that action will appear to move more slowly than at its normal movement. By extension, fast motion is an optical effect where the rate of recording is less than the rate of projection. If fewer frames per second have been filmed, then when projected at the standard rate of projection, it results in faster than normal movement. A specific variation of fast motion is time-lapse photography, which is used to film motion that is not apparent to the human eye, such as the germination of a plant or celestial movements. Time-lapse photography takes still images at large intervals, which are then compressed when projected, allowing normally invisible motion to be seen. A freeze frame is an optical effect that involves the re-photographing a single frame such that the film appears to “freeze” or stop in place, even as it continues to move at 24 fps. The freeze frame creates a literal pause in the narrative action.

VISUAL EFFECTS

We tend to associate visual effects (VFX), or what used to be called special effects, with contemporary filmmaking, but optical modifications to the image have been a part of filmmaking nearly from the start. The widespread use of computer-generated imagery (CGI) in contemporary film troubles the separation between mise en scène and cinematography that this textbook assumes. That is because much of what we see in the image in films today exists only in a virtual environment. The objects characters hold, the costumes they wear, the spaces they move through – often, these do not exist in reality but are digitally created. Visual effects were known as “special” because their use was relatively limited, but this once marginal branch of the industry now arguably resides at its center, affecting every aspect of production. Indeed, visual effects has collapsed the previously distinct phases of production and post-production. Post-production is not really “post-” anymore, since visual effects technicians are involved in the process before and during shooting, not just after. This section outlines many of the common analog (meaning, rooted in physical reality) and digital (meaning, computer-generated) techniques used in cinematic visual effects.

Set Extensions

Because it can be expensive and time-consuming to build full-scale sets, filmmakers often deploy cheaper and quick alternatives to give the impression of a fully realized space for the narrative action. In analog filmmaking, rear projection is a basic type of set extension. In this optical effect, the live action component of the scene is filmed in front of a screen, onto which an image is projected from behind (Figure 35). This is commonly seen in films from classical Hollywood – for example, in a scene involving driving. The characters would be situated in a car in a studio, while the background is rear projected, creating a visual simulation of driving (Figure 36). Viewers tend not to find rear projection very credible in creating a coherent diegesis, because the depth cues of the volumetric live action and the planar rear projection do not align. The effect can therefore look staged or manufactured, but filmmaking often relies on suspension of disbelief from the spectator.

A variation on this process is called front projection. It is also used to combine live action with background footage, but instead of that footage behind projected from behind the screen, it is positioned in front, casting an image on the actors and background screen (Figure 37). Typically, the projector is placed off to the side aimed at a one-way mirror. The mirror reflects the image onto the scene, while the camera films the action through the mirror, capturing the two elements in one image.

Two other practical set extensions rely not on projection but on painted images designed to be seamlessly integrated into the shot. A matte painting refers to a drawn image or painted backdrop that creates a visual extension of a physical set (Figure 38). Director Fritz Lang, for instance, extensively used matte paintings to create the large-scale futuristic city of his film Metropolis (Germany, 1927) (Figure 39).

A glass shot is closely related to a matte painting. Rather than being drawn on an opaque surface, an image is painted on a pane of glass, which is then inserted between the camera and the live action. Charlie Chaplin used glass shots to stage some of his most famous comic feats, including the roller skating sequence in Modern Times (US, 1936). In this scene, Chaplin, while blindfolded, appears to skate perilously close to a ledge in a department store, but the drop of several stories did not exist in physical reality. Instead, a glass shot inserted the appearance of a drop, making Chaplin’s blindfolded stunt look far more dangerous than it actually was (Figure 40).

Playing with Scale

One feature of cinema is that its image has an unstable relationship to scale. It is difficult, for instance, to tell whether an object is large or whether it is simply close to the camera. Also, since a camera lens films from a single-point perspective (instead of the dual perspective of human vision), it can lack the depth cues of ordinary perception. Yet these features give room to filmmakers to exploit the way that film presents scale and depth.

One way is through the use of miniatures. Miniatures are scaled-down models incorporated into the production design of a shot. For instance, it is an expensive, logistically complicated, and potentially dangerous undertaking to stage, for example, a train crash, so visual effects artists will utilize miniatures to do so (Figures 41-42). The viewer is often unable to discern the scale of the crash (what is actually small appears large onscreen).

Similarly, filmmakers use forced perspective when they want to produce the illusion of an exaggerated size difference (Figure 43). Forced perspective is the gimmicky trick of tourist photos – it’s what makes it appear as if someone is holding the Eiffel Tower in their hand. Peter Jackson used this technique in his Lord of the Rings trilogy in order to create the illusion of the diminutive size of the Hobbits compared to other characters.

Layering

Visual effects such matte paintings and rear projection are a matter of combining different elements on set. Other combinatory visual effects involve camera techniques for the layering of images. Superimposition entails the simultaneous overlap of two or more images to create a composite shot (Figure 44).

Double exposure is related but different. It involves filming one shot, rewinding the film reel to a preset marker, rearranging or removing elements on set, and then refilming the scene. The same strip of celluloid is therefore exposed twice (Figure 45).

Compositing

Compositing is the term in cinematography for the combination of separately filmed events into a single cohesive image. Matte painting and rear projection are types of composited images, but the term more commonly is heard in the context of digital effects. Digital compositing refers to the combination of live action and computer-generated imagery. Green screen, for instance, involves shooting live action against a green backdrop, which is subsequently replaced with digitally created imagery (Figure 46-47). It is not uncommon that entire sets are virtually manufactured, with actors playing out a scene entirely against a green blank canvas. Integrating these elements into a single shot is a significant technical challenge, particularly in terms of matching the lighting conditions of the live action foreground to the background elements.

Contemporary filmmaking has developed more sophisticated methods to replace traditional processes of rear projection and green screen filming. Both of those techniques involve static elements. To offer more flexibility, visual effects artists are using LED walls that render a background simultaneous to filming rather than during post-production. The visual effects company Industrial Light & Magic, for example, developed a virtual production set called Stagecraft (or more informally, “the Volume”) to generate backgrounds for the TV series The Mandalorian (Disney+, US, 2019- ). Unlike with static green screens, this LED set adjusts the photorealistic 3D background in response to the movement of the actors and the camera, whose movements and orientation is tracked in real time by the Stagecraft system.

Motion capture and Performance Capture

These techniques of digital filmmaking pertain to how to translate live action into a virtual environment such that digital creations are based on and grounded by physical reality. Motion capture involves the tracking of the movements of a body or object in order to recreate those movements for a digital creation needed to perform those same movements. During motion capture, for instance, an actor is required to wear an assembly of reflective markers that are tracked by cameras so that a virtual model of their movements can be generated. Motion capture is a digital updating of an older technique known as rotoscoping, which was used extensively in early film animation. Rotoscoping involves the projection of live action onto a glass pane so that animators can trace over it, such as when Disney animators used live actors as the basis for the movements of such classic animated characters as Snow White and Sleeping Beauty. Performance capture is a specific variation of motion capture. It entails the capturing of more subtle movements such as facial expressions. Director David Fincher made pioneering use of performance capture for The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (US, 2008), starring Brad Pitt as the title character who ages backwards throughout the film, starting as an elderly man. Rather than casting different actors to play Button at different stages of his life, Fincher used performance capture so as to be able to composite Pitt’s face/head onto the bodies of stand-in actors. The visual effects technicians placed Pitt in a rig comprising 28 cameras arranged around the actor’s head and applied phosphorescent make-up to his face, whose patterns of movements would be tracked by the multi-camera set-up. This recording session resulted in a library of facial expressions that served as the reference for onscreen performance.