Documentary

Film can generally be divided into three categories, which vary depending on the intended purpose of the film. There is narrative cinema, which sees film as a medium of fictional storytelling, and there is experimental or avant-garde cinema, which explores the moving image’s formal possibilities, often through the use of abstraction or visual poetry. Then there is documentary cinema, the subject of this chapter. Documentary film, as the name implies, “documents” the world. Distinct from the imaginary settings and unreal stories of narrative filmmaking, documentary concerns actual people and events. It aims to communicate about factual reality. The name itself originated with one of the form’s earliest and most significant practitioners, John Grierson, who said of Robert Flaherty’s Moana, his 1926 film about Polynesian culture, that it had “documentary value,” suggestive of the evidentiary function of this use of the medium. Grierson characterized documentary film as the “creative treatment of actuality,” and this broad but useful definition demonstrates why documentary encompasses such a wide variety of approaches, from propaganda filmmaking to industrial films, diary films to reality television. This chapter offers a brief history of some of documentary film’s conventional forms and historical movements.

Documentary’s Beginnings

To some degree, all films are “documentary,” insofar as they record some part of the physical reality in front of the camera. In fact, the earliest moving images, dubbed “actualities,” were little more than visual records of everyday life, absent any fictionalization. However, documentary, as a recognizable mode of filmmaking, with its own codes and conventions, only emerged in the 1920s, and its origins are often associated with the films of Robert Flaherty. Flaherty came to filmmaking by way of mining. His expeditions to the Hudson Bay region of Canada originally pertained to prospecting for iron ore, but his interactions with the Inuit communities of that area prompted him to bring camera equipment on subsequent visits to document their culture. His original footage was destroyed in a fire, but the fur trading company Revillon Frères sponsored a return trip in the early 1920s. The resulting film, Nanook of the North (1922), sought to capture the customs of Inuit life in the harsh Arctic environment, including fishing, seal hunting, the building of igloos, and fishing (Figure 1). Wanting to emphasize the similarities of Western and Indigenous cultures, Flaherty centered the film around the family of Nanook, his wife Nyla, and their children. The silent film is simple in its formal presentation, featuring a largely static camera, mounted on a tripod, and follows a seasonal pattern in its construction, beginning in late spring and ending in the winter. Distributors were initially skeptical of the commercial viability of a nonfictional chronicle of an Inuit family, but the film proved to be a box office success. However, Flaherty’s film raises important questions about documentary ethics. Though Nanook of the North was presented as an objective record of Inuit life, Flaherty staged some scenes, including having Nanook recreate actions for the camera that the filmmaker had previously witnessed. The documentary also falsely presented Inuit culture as pre-modern. In one scene, a phonograph record is played for Nanook, who then bites the record, as if he were unfamiliar with the technology. Moreover, the traditional hunting methods seen in the documentary were no longer in use by the Inuit. Rather than present strict factual reality, Flaherty’s documentary offers a sensationalistic image of Indigenous life that exoticizes their differences from Western culture.

Like Nanook of the North, much of early documentary, in the 1920s and 30s, originated from Western ethnographic expeditions engaged in the study of other cultures. The origins of the nature documentary are found here, as illustrated by the films of Martin and Osa Johnson. Following their first film Trailing Wild African Animals (1923), the Johnsons secured the sponsorship of the American Museum of Natural History and the Eastman Kodak Company for a four-year exploration of East Africa. They promoted the resulting film, Simba (1928), as an authentic record of a lion in its natural habitat, promising audiences a privileged view of exotic animals in the wild. Like Flaherty, though, the Johnsons incorporated fictionalized elements into the documentary by borrowing from narrative conventions. Scenes of lion hunting were constructed as dangerous and thrilling adventures, in which the adventure filmmakers supposedly faced near-death in their encounters with untamed wildlife. The Johnsons staged a scene where they hire Lumbwa tribesmen to spear a lion, which in the film is intercut with footage of a different lion hunt filmed elsewhere. The spectator would also be unaware that the hunted lion was purposefully penned in by cars to prevent its escape, allowing it to be killed for the camera. This example of “nature faking” raises similar ethical questions about documentary’s seemingly objective depiction of the real as Flaherty’s reenactments.

Politics and Documentary in the 1930s

In the 1930s, documentary film became an ideological tool of the state, as film was widely recognized as a popular medium capable of influencing public opinion. Throughout the decade, documentary film was used for advancing the aims of the state across the political spectrum, often in outright propagandistic ways. This section will compare three instances of the political use of documentary – first by Nazi Germany, next by the Popular Front in France, and finally by the British Documentary Film Movement.

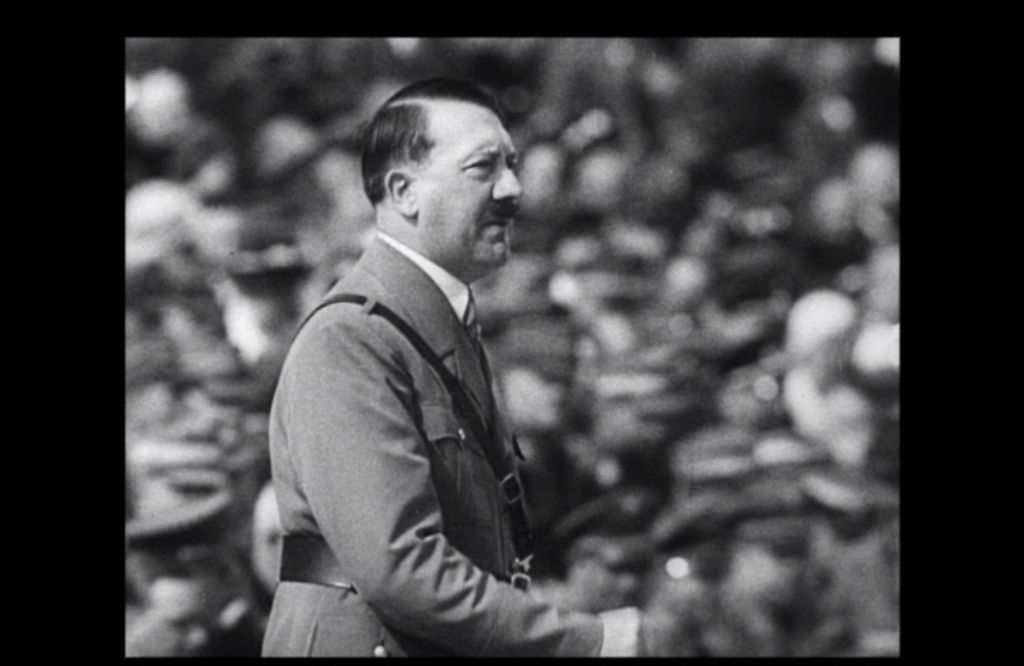

When the Nazi Party was elected to power in 1933, it undertook a gradual nationalization of the German film industry, directly involving the state in film production and distribution. The Nazi Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels recognized the potential of film for reaching mass audiences. In a 1941 speech to the Hitler Youth, Goebbels articulated this view, arguing that “the state cannot ignore the inherently tremendous possibilities” of cinema to “influence and educate adult and mature people on a national level.” The “state sponsorship of films,” he contended, “is now no longer considered disreputable.” Accordingly, the Nazis sponsored documentary films that promoted anti-Semitic propaganda. For example, The Eternal Jew (1940) perniciously drew visual comparisons between Jews and rats, utilizing footage filmed in the Polish ghettos, in order to present Jews as vermin threatening German society. The Nazi exploitation of documentary film, though, is most notable in the films the Third Reich commissioned from actor and director Leni Riefenstahl, including Triumph of the Will (1935) and Olympia (1938). Triumph of the Will is a record of a Nazi Party rally held in Nuremberg in 1933, as it captures the crowds and speeches of the political event (Figure 2). But Riefenstahl was no mere observer. In many ways the rally was staged more for the cameras than for the crowds. Riefenstahl utilized extensive resources to film from a wide range of perspectives. She had pits dug in front of the speakers’ platform to allow for low-angle framing, laid tracks for traveling shots, and built elevators for overhead shots. This infrastructure was designed for political as much as artistic purposes as the elaborate staging help to construct Hitler as a powerful and charismatic leader. Olympia’s ideological message is less apparent. The film documents the 1936 Olympic Games, held in Berlin, and it is divided into two parts, The Festival of Nations and Festival of Beauty. Riefenstahl again uses elaborate camerawork to film the various sporting events, less emphasizing results regarding winners and losers than focusing on the display of athleticism. One sequence, for example, displays a montage of leaping divers from a low angle so that they seem suspended in the air against the sky (Figure 3). Though not as overtly political as Triumph of the Will, Olympia implicitly contributed to Nazi Germany’s mythologizing of its nation and people as strong of body and disciplined in spirit. Despite these films and others, Riefenstahl denied any collaboration with the Nazis, presenting herself in the decades after only an artist and filmmaker.

The political use of documentary in 1930s France arose in response to the looming threat of fascism as signaled by the Nazis’ ascension to power. France witnessed massive street demonstrations by right-wing factions such as the Croix de Feu (Cross of Fire) in 1934, and fearing the rise of fascism at home, the leftist political parties (Communist, Radical, and Socialist) formed a united coalition called the Popular Front to oppose far-right parties in the 1936 elections. The Popular Front successfully won those elections, establishing a unity government in May 1936, after which it passed a series of economic reforms, such as the 40-hour work week. This coalition proved unstable, though, and it cycled through leaders until it fully collapsed in 1938, contributing to France’s defeat by Germany in 1940 and its subsequent occupation during World War II. The Popular Front, while it existed, recognized the potential of documentary film. As Leo Lagrange, the Minister of Sports and Leisure, which oversaw the film industry, said, “My wish is that the cinema, already an excellent leisure activity, may become an instrument for the intellectual and moral development of the masses.” Film was a useful tool in the Popular Front’s electoral victory. Prior to the elections, the Communist Party commissioned director Jean Renoir to make La Vie est a Nous/Life is Ours (1936). The film was financed from small donations collected at party meetings. It combined both narrative and documentary conventions to present the social problems of France at the time and how the Popular Front could help to solve them, effectively serving as a campaign ad before the commercial availability of television.

The situation in England differed from France and Germany. The state helped to finance and produce documentary filmmaking, but not on behalf of a political party, whether of the left or right. Instead, the films of the British Documentary Film Movement, as it is now known, emphasized modest social reforms, liberal democratic values, and the “good” use of documentary film rather than a “bad” use of it. A “good” use of documentary, according to the filmmakers associated with this movement, chief among them John Grierson, promoted social cohesion, while a “bad” use promoted social division. These documentarians were employed by state agencies such as the Empire Marketing Board (EMB), which was established in 1926 to promote British trade. Grierson’s first film for the EMB, Drifters (1929), highlighted herring fishing in the North Sea. This is perhaps not thrilling subject matter, being a government-sponsored nontheatrical short film, but it was Grierson’s institutionalization of documentary filmmaking that constituted his most significant contribution. At EMB, he established a film unit in 1930 that trained a cadre of documentary filmmakers, including Basil Wright, Arthur Elton, Paul Rotha, and Edgar Anstey. As a collective, they produced dozens of films for EMB and developed a distribution network for them, which included the use of traveling vans that could project the films in rural areas. When the EMB shut down in 1933, Grierson set up a film unit at the General Post Office (GPO), where Wright and Harry Watt directed one of the movement’s signature films, Night Mail (1936). This documentary short focused on the logistics of mail delivery, and characteristic of the movement, it combined this quotidian subject matter with formal experimentation – here, the use of voice-over poetry from W.H. Auden and a score written by composer Benjamin Britten. Grierson and the other filmmakers took a few creative liberties with their government sponsorship, making films that fell outside issues related to the GPO. They were especially concerned to document the lives of the working class, and many of their films – including Song of Ceylon (1934) and Coal Face (1935) – focused on laborers and the dignity of work. Toward the end of the 1930s, Grierson turned to private companies such as Shell Oil for the sponsorship of films. The gas industry funded Elton and Anstey’s landmark documentary Housing Problems (1935), about the slum conditions of parts of London. This film is especially notable for its on-site interviews with residents of the slums who testify to the camera about the disrepair of their homes (Figure 4). Government-sponsored housing estates are framed as a solution to these housing problems, underlining the British Documentary Film Movement’s commitment to the idea that documentary could contribute to social reforms and the betterment of society.

Direct Cinema

Direct cinema refers to a type of observational documentary that emerged in the early 1960s. It is associated with directors such as Robert Drew, Albert and David Maysles, Frederick Wiseman, D.A. Pennebaker, and Richard Leacock. A related documentary film movement arose in France parallel to direct cinema known as cinema verité, or “film truth.” Primarily associated with the films of Jean Rouch, cinema verité shares many of the same principles for documentary filmmaking as direct cinema, but there are some important differences between them, as will be addressed below. The central animating idea shared by both direct cinema and cinema verité is the non-intervention by the documentary filmmaker in the events being filmed. A director should not place themselves within the scene, either through editorial commentary or by appearing as a subject of the documentary, as happens in the documentaries of Michael Moore, for example. This is sometimes characterized as a “fly on the wall” approach, since the documentarian is meant to be a neutral observer of events. A filmmaker working within this tradition would not, in contrast to Robert Flaherty, restage events for the camera. The purpose of these principles is to let reality itself be expressed through the film. In this regard, direct cinema stands in stark opposition to the political or propagandistic uses of documentary discussed in the previous section.

Direct cinema’s arrival is commonly linked to new developments in film technology. Improvements to 16mm cameras enabled them to be lightweight and quiet in their operation (older cameras required the use of an insulating “blimp” to dampen the noise they produced). These less cumbersome cameras allowed filmmakers to be more mobile and to achieve greater proximity to their subjects. Likewise, sound technology got lighter and therefore more portable. Through the use of magnetic tape recorders, filmmakers could record on-site sound regardless of where their subjects moved, especially as this type of audio recording did not need to be physically tethered to the camera for coordinating synchronization. Moreover, the cameras that direct cinema filmmakers used were “reflex” cameras, which used mirrors to produce a “live” image of what was being recorded, allowing the camera operator to make immediate changes to framing and focus (an essential requirement for recording an unfolding event as it happens).

One of the first and best-known examples of direct cinema – the 1960 film Primary – demonstrates the aesthetic possibilities that were realized by means of these technological developments. The film documents the primary campaigns of John F. Kennedy and Hubert Humphrey for the nomination of the Democratic Party in Wisconsin in the run-up to the 1960 U.S. presidential election. Robert Drew and his collaborators including Albert Maysles and Pennebaker were granted significant access to the candidates, capturing them both in candid and unguarded moments that would have seemed to contemporaneous audiences as striking in its authenticity. In one of Primary’s signature shots, the camera trails behind Kennedy from a slightly elevated position as the candidate presses through a crowd of supporters, greeting them as he goes, and then continues to follow him as he ascends a narrow staircase before finally arriving to a stage, where Jackie Kennedy and a lively crowd have gathered to hear him speak (Figure 5). As indicated by this shot, direct cinema sought a heightened sense of realism through this close, intimate contact with its subjects. This mode of documentary film wanted the dramatic structure of the film to be derived from the events themselves, which sometimes risked an uneventful portrayal.

Several of the direct cinema filmmakers made documentaries about musicians and live music events, including Don’t Look Back (Pennebaker, 1967), Monterey Pop (Pennebaker, 1968), and Gimme Shelter (Albert and David Maysles, and Charlotte Zwerin, 1970). The concert event was well-suited to the techniques of direct cinema, and the result was that these films collectively provide a documentary record of the 1960s counterculture. Don’t Look Back documents Bob Dylan’s 1965 concert tour in England. The film includes performances by Dylan at the Royal Albert Hall in London and at a voter registration rally in Mississippi, as well as a more candid performance by Joan Baez as she hangs out with Dylan in a hotel room. Despite this behind-the-scenes access, Dylan appears as a mercurial figure, who manages to deflect or redirect interview questions. The concert documentary Monterey Pop was one of Pennebaker’s next films, and it documents the Monterey International Pop Festival in 1967, which featured musical acts such as The Mamas & the Papas, Simon & Garfunkel, Jefferson Airplane, and The Who. An extended sequence near the end of the documentary presents a sitar performance by the Indian musician Ravi Shankar, as hippie youth watch from the fields surrounding the stage. A more controversial concert film was released two years later. The Maysles’ Gimme Shelter portrays the infamous 1969 Rolling Stones concert in Altamont, California, where members of the biker gang Hells Angels, hired as security for the event, killed a concertgoer (Figure 6). The documentary captures the moment of the killing, as well as the generally raucous atmosphere of the concert. The peace-and-love vibe of Monterey Pop turned decidedly sour in Gimme Shelter, signaling an end of sorts to the counterculture.

The related movement of cinema verité in France shared many of the same principles regarding documentary filmmaking as the U.S.-U.K.-based direct cinema. However, one distinguishing factor between them is cinema verité’s use of reflexivity. The movement’s figurehead, Jean Rouch, wanted to break down the barriers between filmmaker and subject by involving those subjects in the construction of the film. The documentarian would be an observer, as in direct cinema, but Rouch contended that the presence of this observer (and the camera) changed the nature of what it filmed. The encounter between filmmaker, camera, and participant would be mutually constructed. For example, in the movement’s signature film, Chronicle of a Summer (1960), which Rouch made in collaboration with sociologist Edgar Morin, the directors interview a diverse array of individuals living in postwar Paris about their lives and their attitudes toward personal happiness. The filmmakers then screen this footage for the participants and solicit their comments about what they said about their own lives and how the film portrayed them. In other words, within the documentary is a sequence that comments on the documentary. This is characteristic of the reflexive approach of cinema verité that makes the documentary subjects active participants in their own representation.

Documentary Film and Social Movements

At the risk of overgeneralizing, documentary filmmaking of the 1970s and 80s broke from the observational style and presumed neutrality of direct cinema by creating films that were more participatory, personal, and political. These new directions in documentary coincided with the public visibility of diverse social movements organized around advocacy and activism for identity-based groups facing historical discrimination – including the women’s movement, the Black liberation movement and other strands of Black civil rights, the American Indian and Chicano movements, and gay and lesbian liberation, including, later, AIDS activism. Documentary provided a means of self-representation for these historically excluded groups, as they sought to tell their own stories and document their everyday lives. This mode of filmmaking functioned both as part of their public advocacy and as a tactic for forging communities through the depiction of shared experiences.

The emergence of second wave feminism in the 1970s included a criticism of Hollywood narrative cinema’s representation of women, particularly for its stereotypical depiction of female characters, and documentary film provided a less expensive mode of filmmaking for developing alternative representations that would more accurately portray women’s lives. More than that, women-directed documentaries could function as instruments of feminist consciousness-raising, referring to the processes by which women gained heightened awareness of their social marginalization. As a counter to the falsity of Hollywood representation, feminist documentary filmmakers initially appealed to realist strategies. The 1971 documentary Growing Up Female, directed by Julia Reichert and Jim Klein, interviewed several girls and woman, ranging from a teenage schoolgirl to a married mother of three. In these interviews, they speak not only about their lives but also about the pressures placed on them as women, as they confront societal expectations and cultural stereotypes. A similar documentary titled The Woman’s Film (San Francisco Newsreel, 1971) profiled some of the members of a women’s support group. As a demonstration of the feminist slogan “the personal is political,” the film connects their individual stories to activist rallies and protests, emphasizing that communities of women have channeled their personal frustrations into collective action. Indeed, The Woman’s Film is an example of collective filmmaking, characteristic of second wave feminism, in which women, untrained in media production, engaged in acts of self-representation.

The initial realist approach of feminist documentary – in which to some degree it was sufficient that women’s stories, long absent from cinema, be recorded on film – was soon superseded by a reflexive approach that involved experimentation with cinematic form. In a 1973 essay, “Women’s Cinema as Counter Cinema,” Claire Johnston articulated this position, writing that “it is not enough to discuss the oppression of women within the text of the film; the language of the cinema/the depiction of reality must also be interrogated, so that a break between ideology and text is effected” (225). The film camera is not “innocent,” Johnston argued, or neutral like the direct cinema filmmakers imagined. A feminist cinema needed to adopt a critical stance toward film’s construction of reality. As an example, the short documentary Réponse des Femmes [Women Reply] (1975), directed by French filmmaker Agnès Varda, features generations of women interrogating the question “what is a woman,” offering a series of counter-responses to patriarchal notions of femininity (Figure 7). Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman offers a more austere film than Varda’s playful documentary, but one that is no less experimental in its form. In the autobiographical work News From Home (1977), Akerman presents a series of long takes of locations in New York City while letters from her mother are read in voice-over. The letters capture the feeling of estrangement from home (“You still haven’t sent pictures,” her mother writes her). That Akerman only offers a portrait of herself and her life in New York as refracted through these letters, rather than presenting her experiences directly, serves an illustration of feminist documentary’s reflexive approach.

Feminist documentaries of this period were also concerned with depicting counter-histories, referring to historical events that have been overlooked because they primarily involved women or aspects of well-known historical events where the involvement of women had been ignored. These documentaries sought to redress the exclusion of women’s voices in historical narratives. Union Maids (1976), by the directors of Growing up Female, Julia Reichert and Jim Klein, profiled and interviewed the only three women included in the oral history of working-class activists Rank and File, written by Staughton Lynd and Alice Lynd. Also concerned with the lives of the working class, Harlan County, USA (1976) documented a strike by Kentucky coal miners, where the role played by women was integral to sustaining this labor action (Figure 8). The film’s director Barbara Kopple and her crew put in substantial effort to gain the trust of the striking workers. The film was awarded an Academy Award for Best Documentary. Finally, Ana María García’s documentary La Operación (1982) provided a historical account of the U.S.-led sterilization program of women in Puerto Rico, and included interviews with women victimized by the mass sterilization conducted in this U.S. territory during the 1950s and 1960s.

Documentaries by and about racial and ethnic minorities also proliferated beginning in the 1960s as media institutions undertook efforts to diversify and expand their reach to different audience demographics. Similar to the women’s documentary cinema of this period, Black filmmakers focused extensively on counter-histories and critiques of American media for its exclusion of Black voices and perspectives. A number of Black-directed documentaries of the early 1970s centered around notable African-American figures, such as boxer and activist Muhammad Ali (A.ka. Cassius Clay [1970]), early 20th Century boxer Jack Johnson (Jack Johnson [1970]), and civil rights activists Malcolm X (Malcolm X [1972]) and Fred Hampton (The Murder of Fred Hampton [1971]). Other documentaries, such as Black Shadows on a Silver Screen (Steven York, 1975), sought to address the limited and stereotypical representation of Black characters in film and television history, offering a critical perspective on the marginalization of Black experiences across media platforms. Later, director Marlon Riggs produced similar critical media histories. His 1987 documentary Ethnic Notions: Black People in White Minds compiled historical representations of African Americans as a demonstration of the media distortion of Black lives onscreen. In a related film released in 1989, the documentary Color Adjustment, Riggs takes a similarly critical view of Black representation in prime-time television programming. While commercial television trafficked in stereotypes of Black people, public television during this period functioned as an important source of institutional support for documentary films about the histories of African Americans. Most notably, PBS distributed the 14-hour documentary series Eyes on the Prize (1987-1990), produced by the African-American-owned production company Blackside, Inc. Across more than a dozen episodes, the series recounted the history of the American Black civil rights movement, utilizing archival footage and filmed interviews to provide an extensive account of the movement’s important figures and milestones, such as the 1963 March on Washington (Figure 9).

Documentary filmmaking provided the means for self-representation for other racial and ethnic minorities. Also appearing on PBS, Who Killed Vincent Chin? (1987), directed by Christine Choy and Renee Tajima-Peña, focused on the 1982 murder of 27-year-old Vincent Chin by two White autoworkers who mistook Chin as Japanese and then fatally bludgeoned him with a baseball bat. The two men were motivated by anti-Asian bias stemming from resentments about the Japanese auto industry harming American car manufacturing. The documentary recounts the murder, which took place in Detroit, and the angry community response after the perpetrators were only given probation and a fine after pleading guilty to the crime. Filmmaker Arthur Dong has directed, among other films, documentaries dedicated to examining the Asian-American experience, particularly of Chinese immigrants. His 1989 film Forbidden City, U.S.A. recovers the history of Chinese stage performers in nightclubs in urban Chinatowns in the 1930s and 1940s, who pursued song and dance as their means of assimilation to American society. More recently, Dong released Hollywood Chinese (2007), which similar to Riggs’s documentaries, offered a critical history of the depiction of Chinese characters in Hollywood cinema.

In 1969, the Stonewall Riots kicked off the modern gay liberation movement. While there were certainly gay and lesbian civil rights organizations prior to this grassroots uprising against police harassment of queer communities at a Greenwich Village bar, LGBT activism dramatically increased its public visibility in the 1970s, exemplified by the founding of gay pride marches. Documentary filmmaking functioned to capture this burgeoning movement and provide affirmative stories of LGBT people in stark contrast to their negative portrayals in mass media. A significant early example is Word Is Out: Stories of Our Lives (1977), which was produced by a filmmaking collective. Structured around the principle of “coming out,” the documentary featured interviews with more than 200 gay and lesbian individuals who were asked to share their experiences of being gay in America. The simple act of telling their stories publicly was an important response to the historical exclusion of LGBT people from mass media representation. LGBT documentary filmmaking of this period also focused on recovering the histories of its culture and communities. The paired documentaries Before Stonewall (1984) and After Stonewall (1999) narrated significant moments in LGBT history, such as the “lavender menace” of the persecution of gays under 1950s McCarthyism and the AIDS activism of the 1980s. Another landmark documentary arrived in 1984 with the release of The Times of Harvey Milk, directed by Rob Epstein and Richard Schmeichen, which would win the Academy Award for Best Documentary. The documentary profiled Harvey Milk, who became the nation’s first openly gay public official when he was elected to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors (Figure 10). Milk was assassinated, along with San Francisco mayor George Moscone, by one of the other members of the Board of Supervisors, who later advanced at trial defended his actions with the so-called “Twinkie defense,” in which he claimed diminished capacity in part because of his junk-food diet. The 1990 documentary Paris is Burning, directed by Jennie Livingston, highlighted the Harlem drag balls where Black and Latino gay men and transgender individuals participate in various competitive categories of drag performance (Figure 11). The film provided notable public visibility to a historically marginalized community – in fact, the film gave rise to the early 1990s popularity of vogueing and to the widespread dissemination of slang terms such as reading and shade – while at the same time, it was critiqued for being a potentially exploitive depiction of a minority community that the filmmaker, a White woman, was not a part of. By contrast, an insider perspective on Black gay culture can be seen in another documentary by Marlon Riggs titled Tongues Untied (1989). Shot on video, the documentary features a range of visual and rhetorical strategies, including on-camera confessionals and performative sequences, such as when several participants demonstrate different forms of finger snapping as one expressive gesture used by Black gay men.

Documentary Goes Mainstream

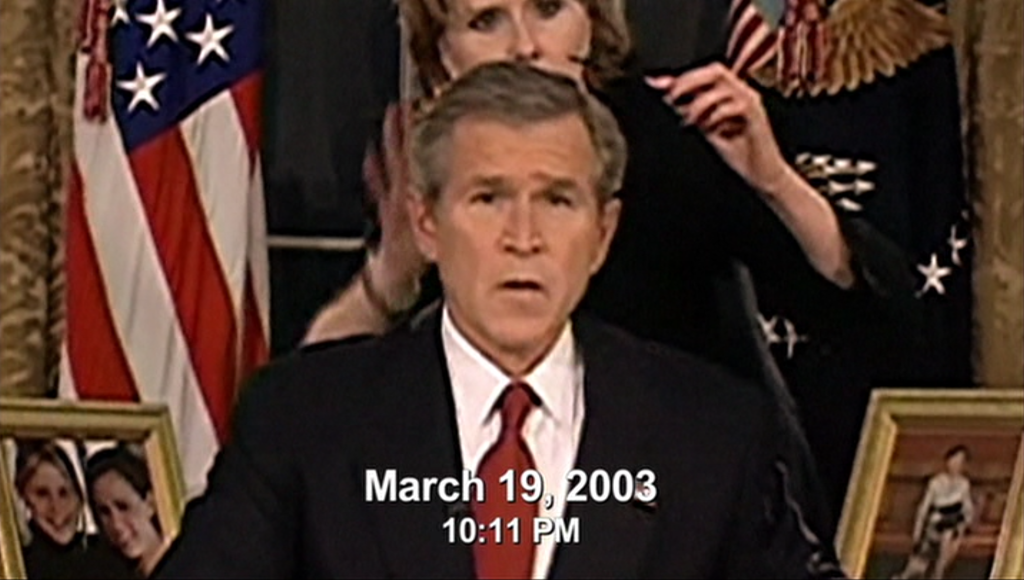

Documentary film, for most of its history, remained a specialized or niche segment of the overall film marketplace – more the province of the art house than the multiplex. That changed in the early 2000s, when a number of documentary films, particularly those released in 2003 and 2004, garnered significant box office revenues, far exceeding the normal range for what a documentary typically earned. Chief among these was Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004), directed by Michael Moore, which stridently criticized the George W. Bush administration’s response to the terrorist attacks of 9/11 (Figure 12). Moore’s film brought in a record-breaking $119 million at the domestic box office, clearly demonstrating the commercial potential for documentary film at this moment. Other films enjoyed the benefits of documentary’s newfound popularity, including: Spellbound (Jeffrey Blitz, 2002), Winged Migration (Jacques Cluzaud, 2001), Super Size Me (Morgan Spurlock, 2004), The Fog of War (Errol Morris, 2003), March of the Penguins (Luc Jacquet, 2005), Capturing the Friedmans (Andrew Jarecki, 2003), Touching the Void (Kevin Macdonald, 2003), The Corporation (Mark Achbar and Jennifer Abbott, 2003), and An Inconvenient Truth (Davis Guggenheim, 2006).

These documentaries cover a broad range of topics, from McDonald’s to climate change, so it was not necessarily their subject matter that explains their popularity – though films such as Capturing the Friedmans anticipate the strong audience desire for true-crime narratives which have been central to documentary filmmaking in the streaming era. What then explains the sudden box-office success of documentaries during this period? Film distributors play a key role in this story. Distribution companies are the middlemen between producers and audiences. They acquire and market films to the public, overseeing their theatrical release and often their subsequent release on DVD, cable television, and streaming platforms. The intensive focus on blockbuster or event films by Hollywood studios opened up an opportunity for smaller distributors to provide alternative programming to audiences who were interested in other types of content. In the 1990s, independent narrative feature films often served this purpose, but by the 2000s, documentary films offered an additional option. Distributors such as Magnolia Pictures or ThinkFilm heavily promoted their documentary releases in ways that were previously reserved only for narrative films. Documentaries received wider releases than before, sometimes opening on hundreds of screens rather than only a few.

In order to target these general audiences, distributors sought out documentaries with crossover appeal. Take, for example, March of the Penguins, which earned a stunning $77 million in its North American release. The documentary depicts the remote habitats and mating rituals of emperor penguins in Antarctica, emphasizing the harsh nature of surviving in subzero temperatures (Figure 13). The film is of French origin, but the film’s distributor Warner Independent Pictures made changes that were designed to appeal to American audiences. Most significantly, the film’s original voiceover narration, which tended to focus on the perspectives of the penguins, was replaced with new commentary, narrated by Morgan Freeman. This new voiceover took a “family friendly” approach, which framed the mating pairs as romantic couples and made anthropomorphic comments that compared penguins to human nuclear families. While perhaps compromising the educational value of the documentary, the change achieved its marketing purpose, as March of the Penguins demonstrated that nature documentaries could be marketable family entertainment, similar to an animated film. In fact, Warner Bros., the parent company of Warner Independent, would a year later release Happy Feet (George Miller, 2006), an animated musical about penguins.

The commercial potential of documentary film persists into the streaming era, as Netflix especially has specialized in true-crime documentary series such as Making a Murderer (2015-2018) and Murdaugh Murders: A Southern Scandal (2023). Contemporary audiences, raised on reality television, are perhaps predisposed to seek out nonfiction media, and documentary production is less expensive than producing an original narrative series, providing clear incentives for streaming platforms to invest in this type of content. However, there have been ethical questions raised in response to the increasingly competitive marketplace for original documentary content. In the case of documentaries about celebrities or other notable public figures, such as athletes, the subject of the documentary has sometimes served as a producer, giving them some authority as to what is included. This seeming conflict of interest potentially turns documentary filmmaking into an extension of promotion or public relations. Moreover, as documentary producers compete for access to compelling stories, some now pay subjects for their participation, a practice long consider to be a violation of documentary ethics. As artificial intelligence become increasingly available to filmmakers, these tools present ethical problems for their application to documentary film. Director Morgan Neville used AI to recreate the voice of celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain for Roadrunner (2021), and so did director Andrew Rossi when he wanted stories told by Andy Warhol to be narrated in the late artist’s voice for his documentary series The Andy Warhol Diaries (2022). These issues are a reminder that documentary, because it portrays real people and events, has ethical obligations that do not necessarily apply to narrative film.